The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity. Click the PDF icon to download the presentation slides.

Age-Related Hearing Loss

Audience Question

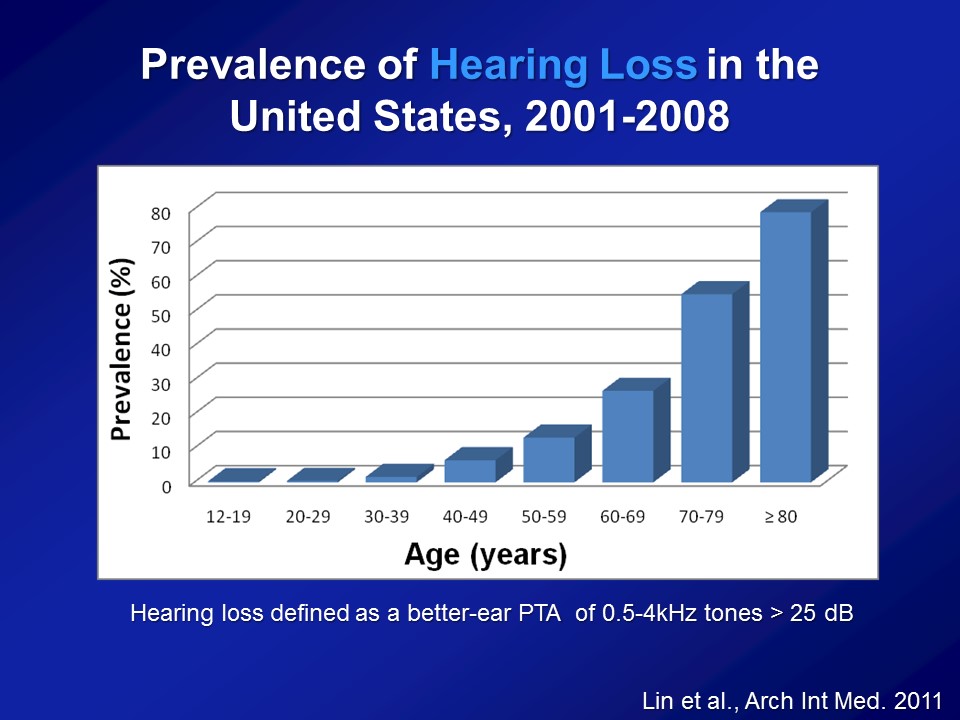

I just need a point of clarification going back to slide number three. That prevalence that you have from age 12 on to 80 – where’s the source of this data? Can you clarify where you got it?

This data is from– It’s called the National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys which are basically studies done by the US government, CDC, such as NIH. NHANES is basically a– They do this like every two years. They basically get the entire sample of the entire US population, measure blood pressure, heart rates, get blood. Some years, many years now, they’re doing pure-tone audiometry. So, basic conventional pure-tone audiometry in a mobile booth, that’s this big trailer. Yeah. Great question. Thank you.

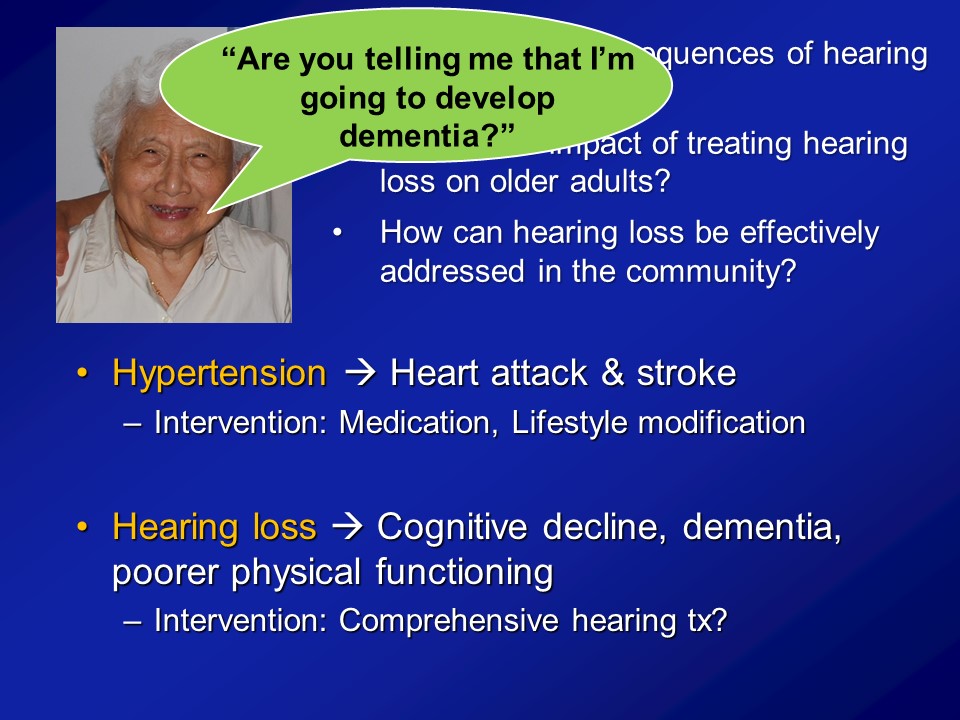

All right. So what I’d like to do again today over the next spent hour, so again please chime with the questions whenever you guys like, is looking at these three questions and how– So at least my group so far has been addressing this. And the first one I talked about today is, specifically what we think now maybe the consequences of hearing loss in older adults.

What are the consequences of ARHL for older adults?

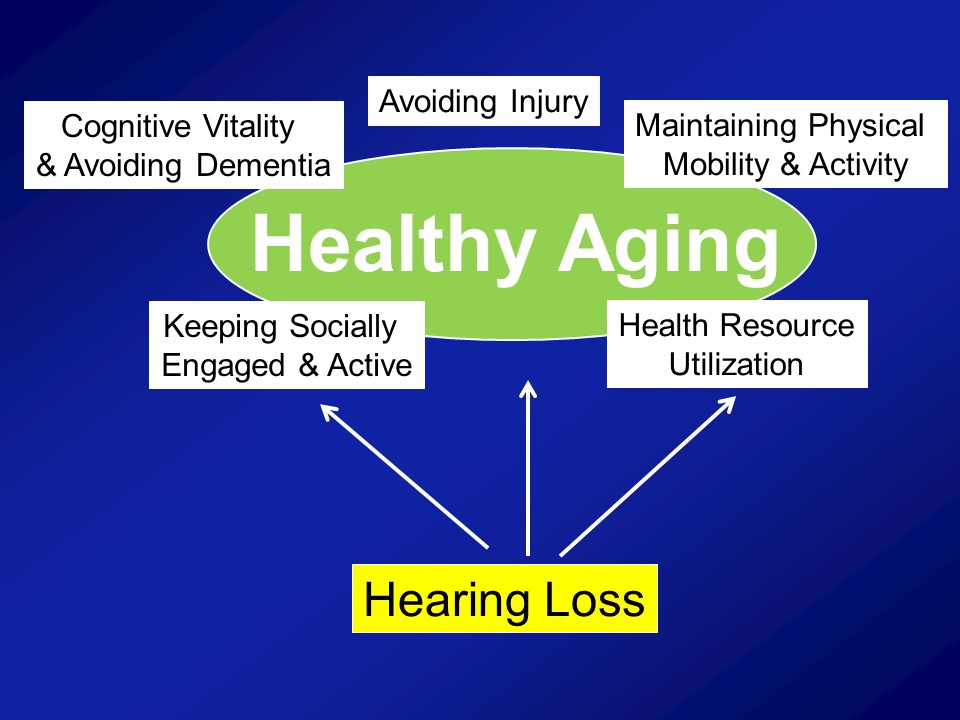

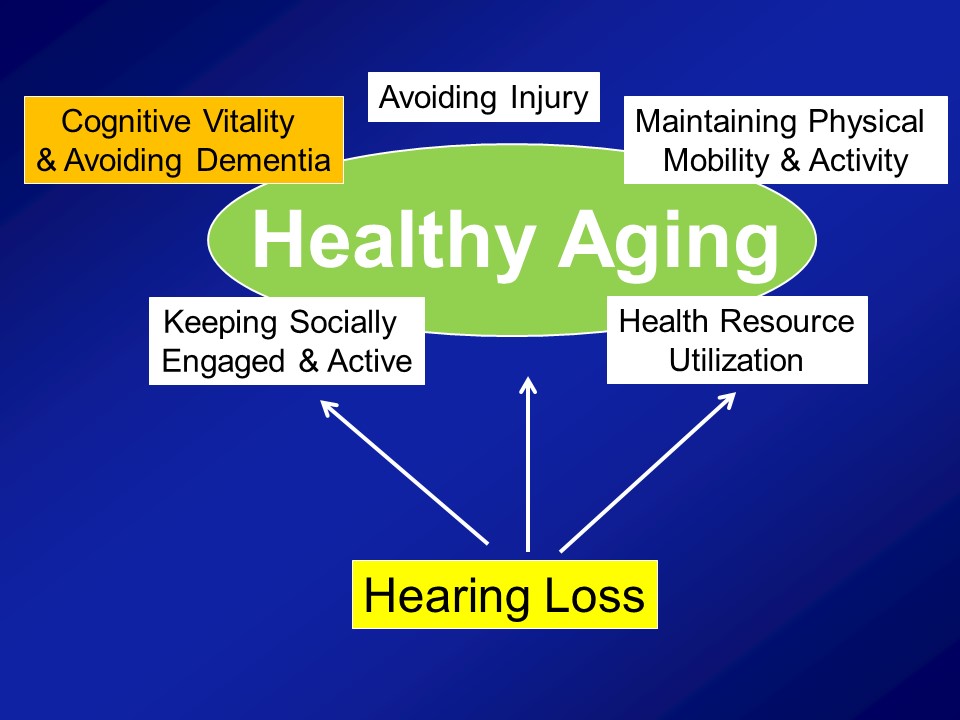

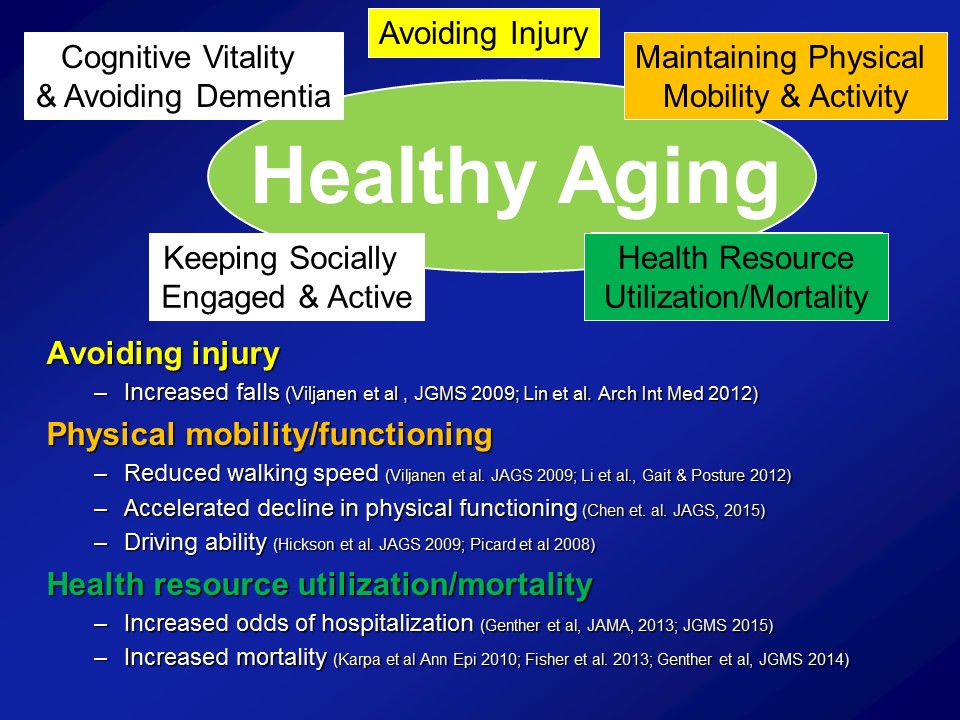

So I warned you about this before and that’s why I mentioned again is that– again, my research fundamentally comes from my perspective as being a gerontologist and not an otologist. And what I mean by that distinction is that, what I actually care about from the research perspective is actually this. I actually don’t care about hearing loss directly at all. The reason why I do my research is because of this. I mean, this is the end-all, be-all for me in terms of what I care about. And I think healthy aging is a concept that all of us– you sort of know it when you see it. We’ve all heard this term before.

So, for example this is– Does anyone know who this man is? Oh, all right. So– There’s some runners in this room though. All right. This man should be your idol. This man is Fauja Singh also nicknamed the “Turbaned Tornado”. He is 101 in this photograph. And I think now he’s 103 still living in London, and he ran his last marathon when he was 100. All right. And now he’s officially retired and I think he only does like 10Ks. Yeah, it’s really, really impressive. So clearly a very vibrant dynamic picture of healthy aging, undoubtedly. In contrast an older man with mobility impairments in nursing home, probably what many of us consider not to be sort of ideal or healthy aging. Contrast atop left, a grandmother interacting with her granddaughter on a daily basis, taking her to school, being home when she comes home. Clearly I think many us agree a very vibrant picture of healthy aging. And finally in contrast again is sort of the subject of today’s talk, other people’s talk today is a woman with early dementia in a nursing home, probably what many of us consider not to be healthy aging.

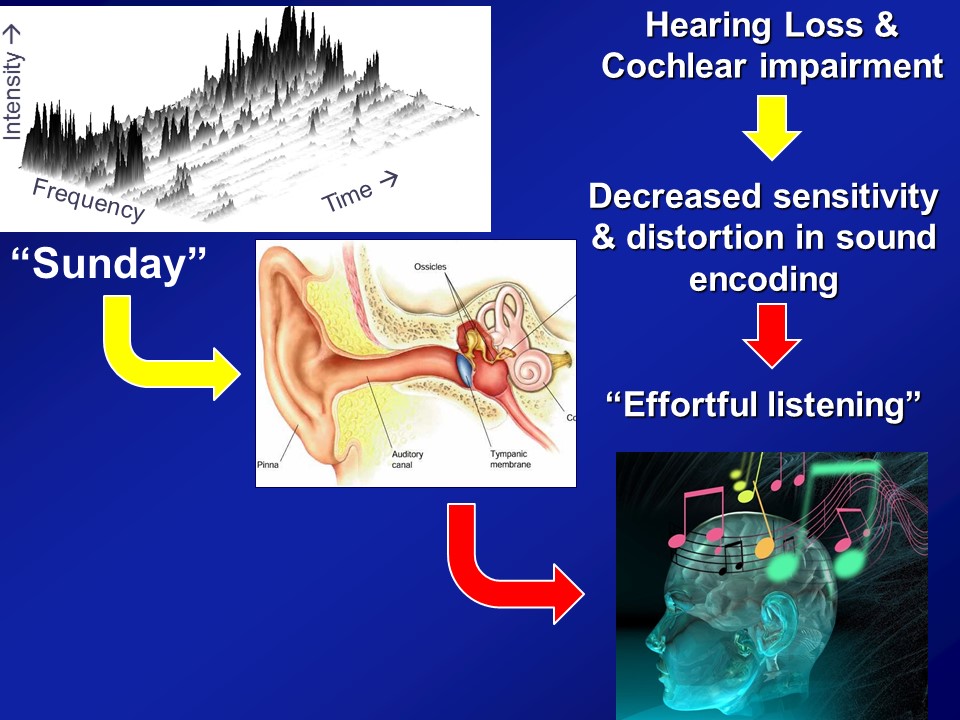

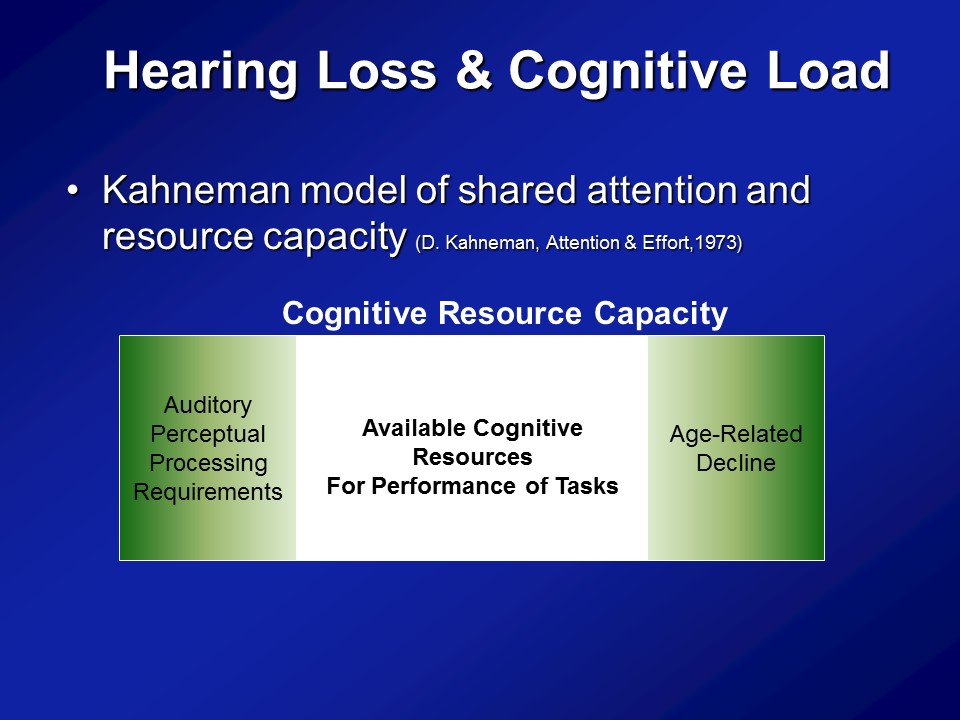

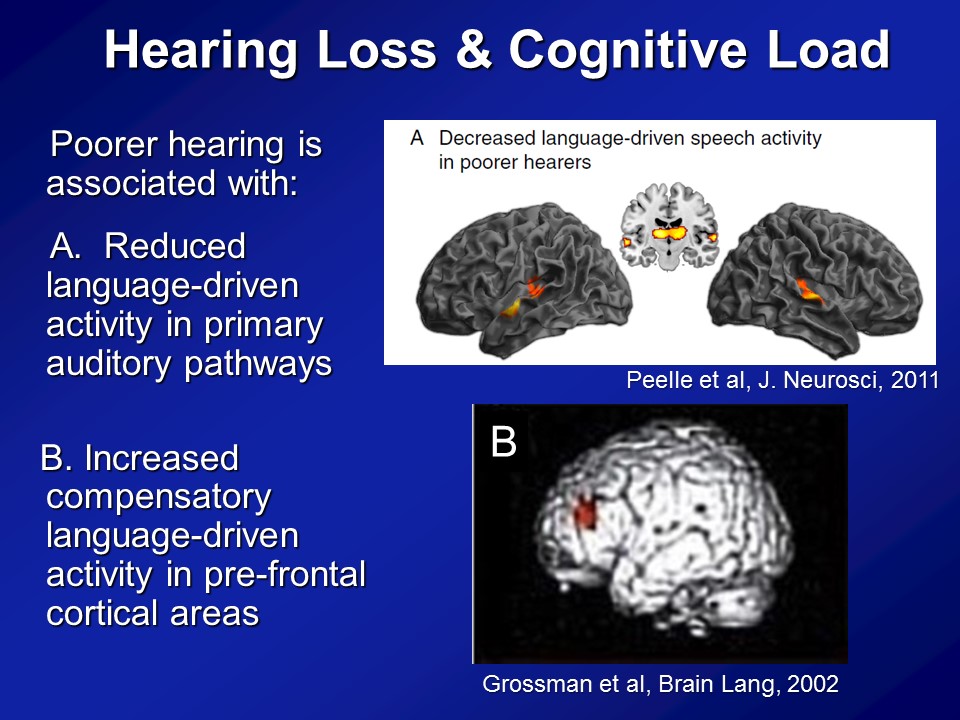

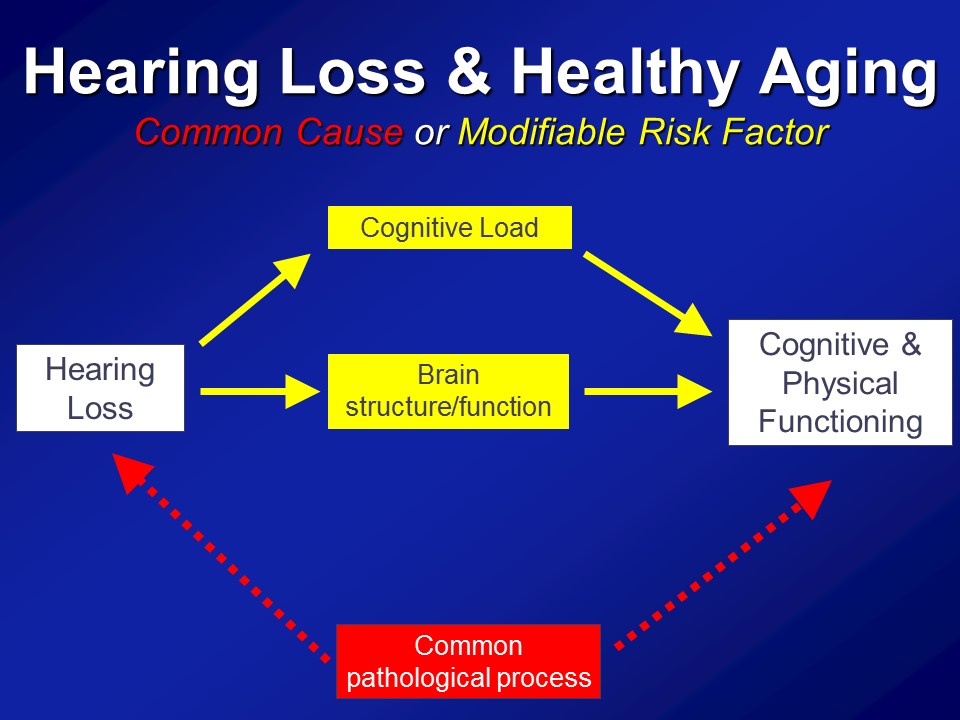

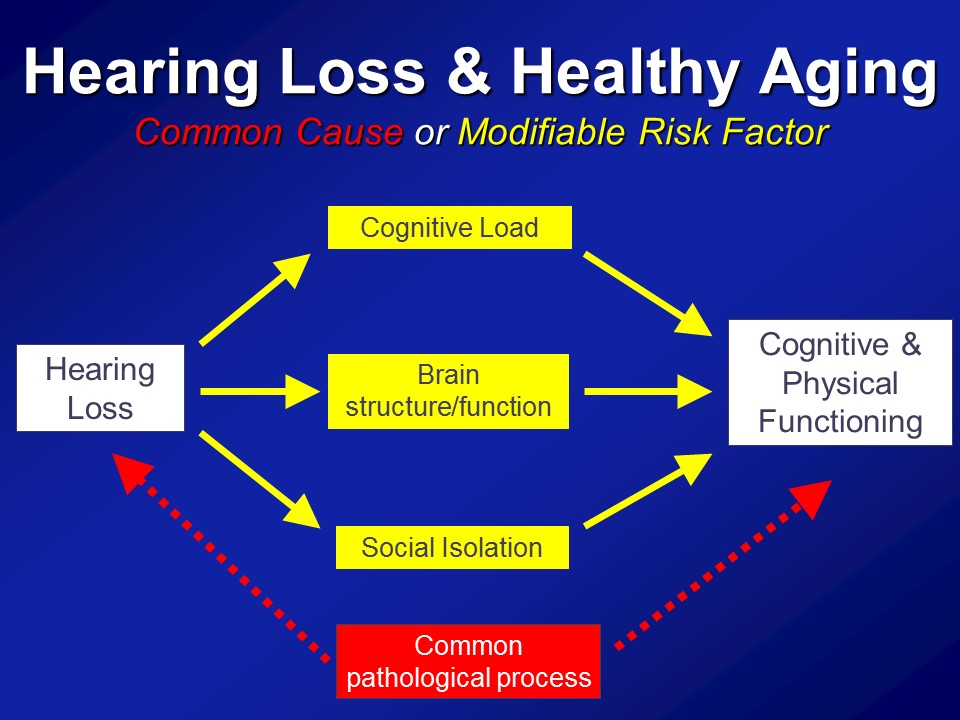

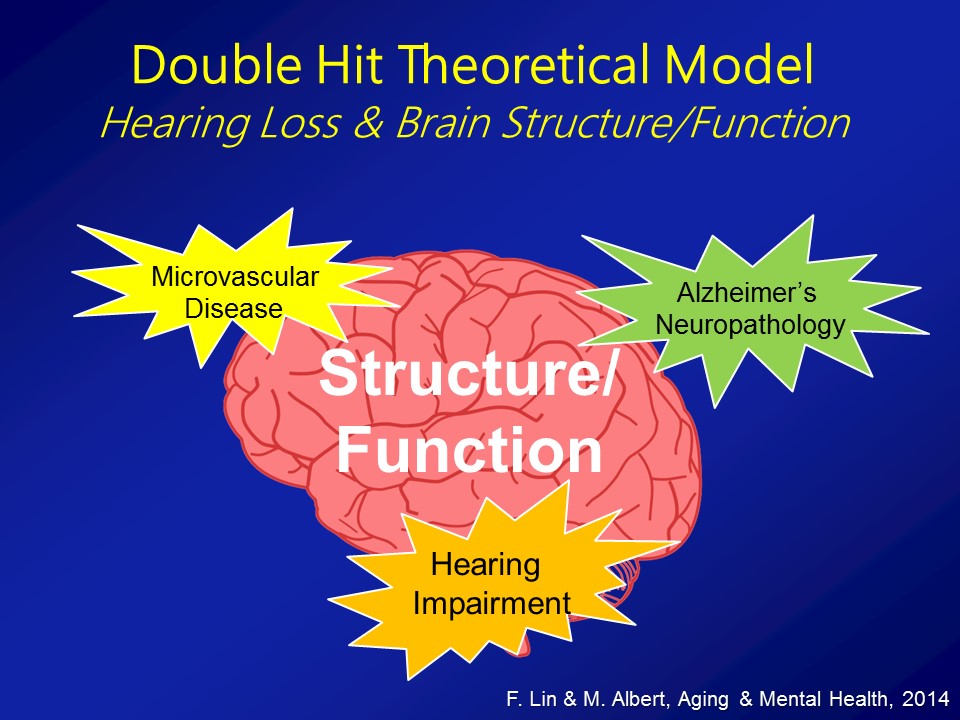

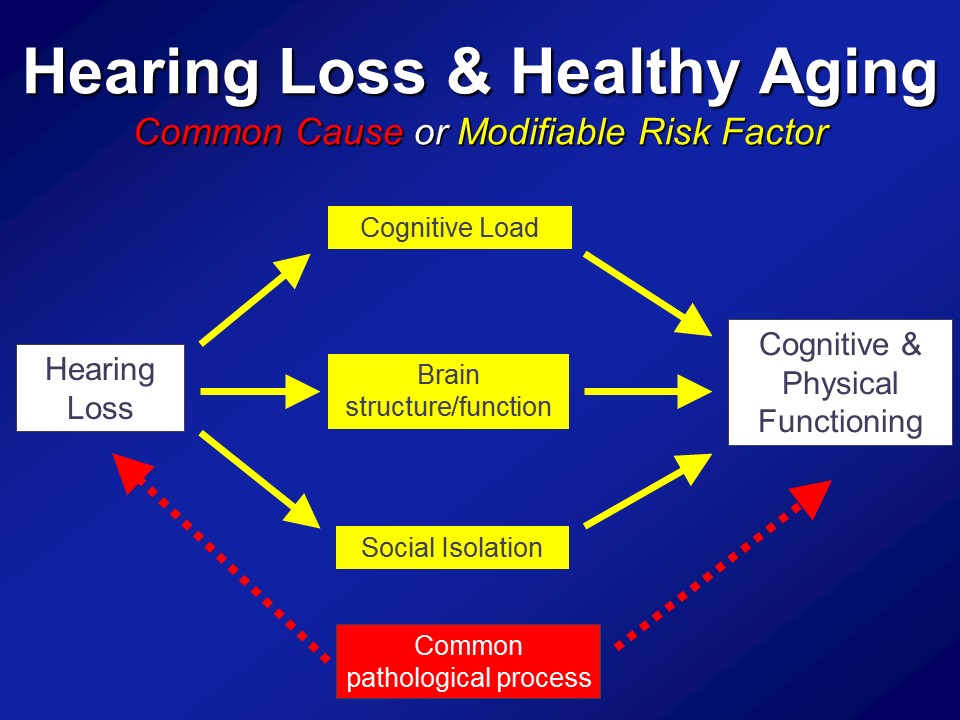

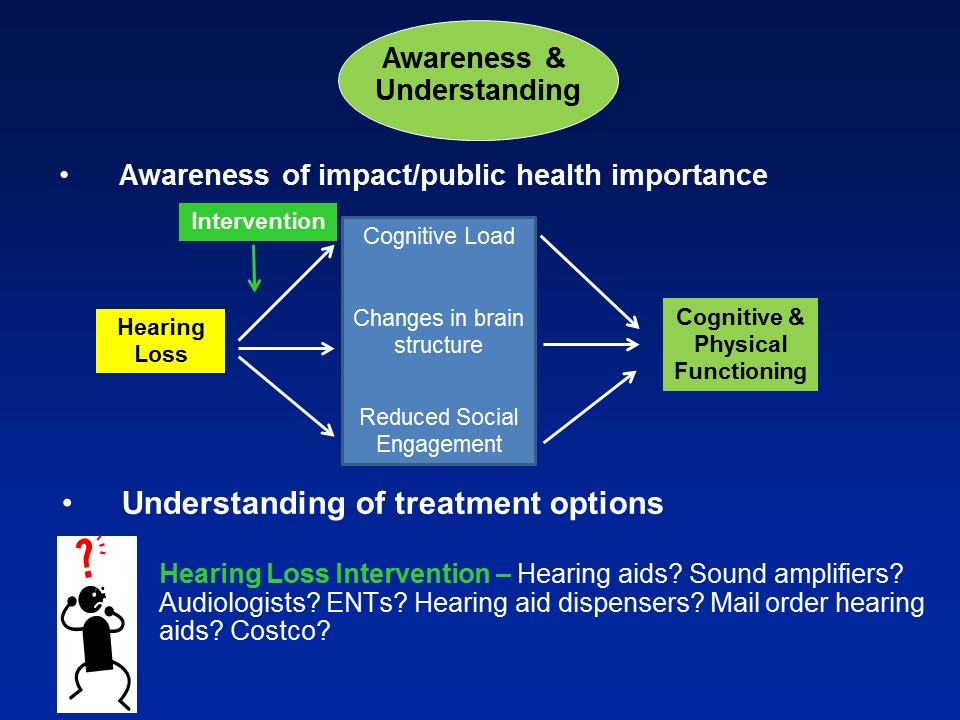

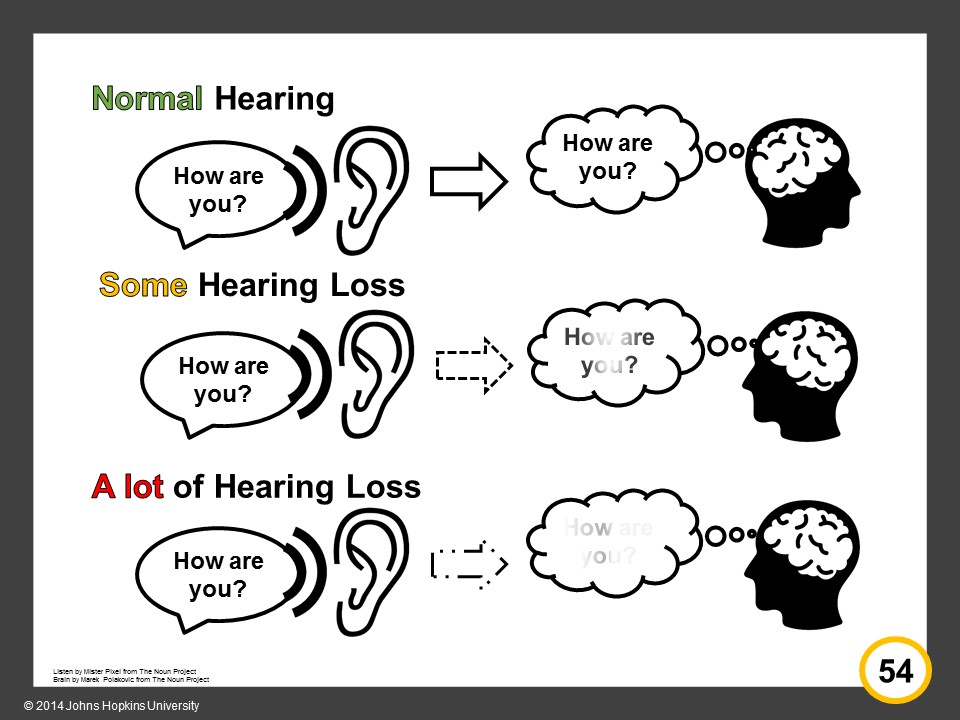

Hearing Loss & Cognitive Load

Brain Structure /Function

Social Isolation

The third pathway which I’ll mention now, which is not mutually exclusive in the other two, it’s probably the most intuitive for people in this room, for any of us in this room actually, for even society as a whole is that, that hearing loss in some way, shape, or form can lead to loss of social engagement and some degree of social isolation. It seems almost self-evident.

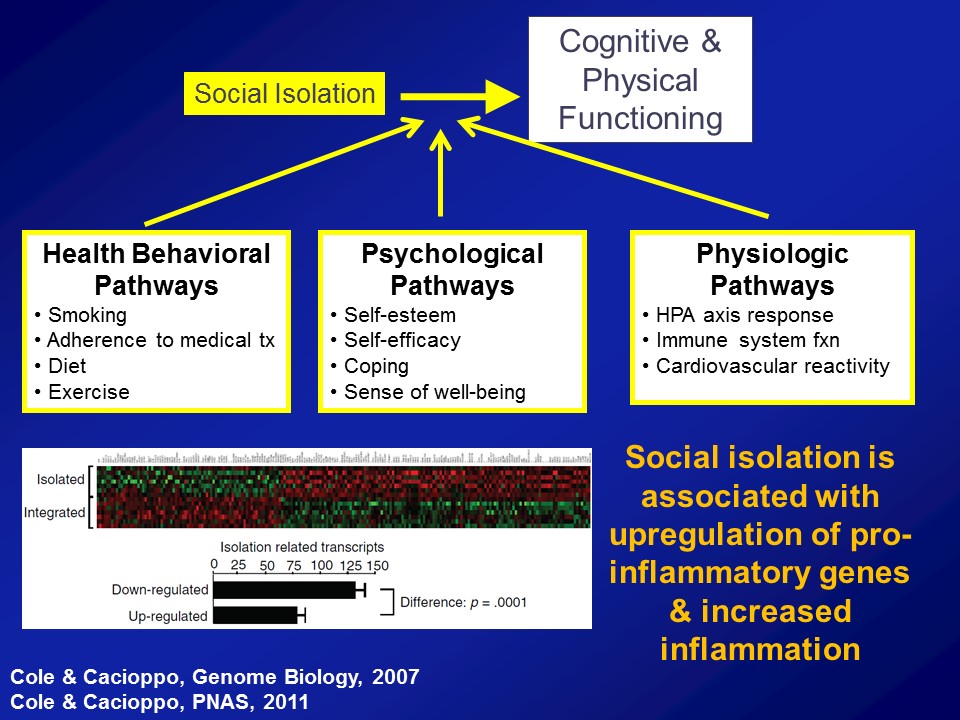

Yet the amazing thing about this is that if we believe this as a field, if we believe this as a society, that hearing loss could affect our ability to engage socially, that is something fundamentally profound. Because I’ll tell you if you delve now into a gerontologic literature going back over 100 years now since the day of a guy called Durkheim, we have long known that social isolation is arguably one of the most important predictors of morbidity and mortality in older adults. And I tell you, this is well studied– social epidemiologists study these pathways. And they’re well established that we know that people who are socially isolated as a whole, on average, have poor health behavioral pathways in terms of adherence to medical treatments, psychological pathways of self-esteem, self-efficacy. But what’s probably the most fascinating work nowadays is an increase in looking at that there are physiologic manifestations too, where we actually see altered immune system reactivity and poor immune system function in people who are socially isolated.

So this comes out of the work of a person called John Cacioppo in Chicago where this was– a couple of studies now where if you look at gene transcript profiles, leukocytes, white blood cells and people who are socially isolated on top versus people who are socially integrated on the bottom, what you see consistently is that people who are socially isolated have upregulation of proinflammatory genes. An inflammation or inflammaging in many ways is sort of the final common pathway for a lot of aging processes. So directly providing a physiologic substrate now for why for many, many– over a century now, isolation is a very, very important predictor of morbidity, mortality in older adults, right.

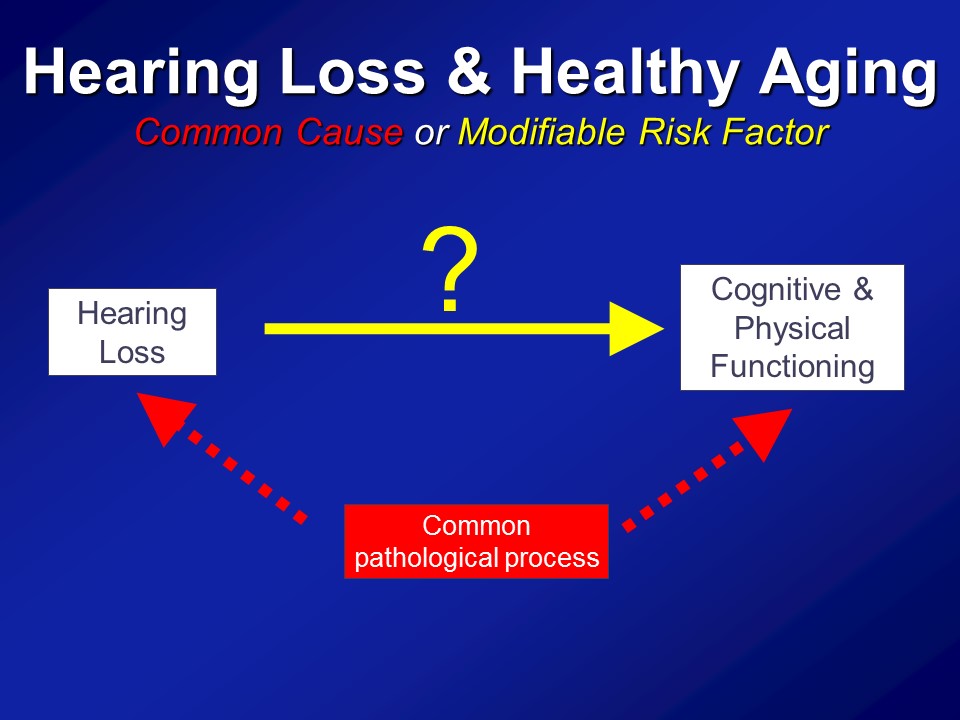

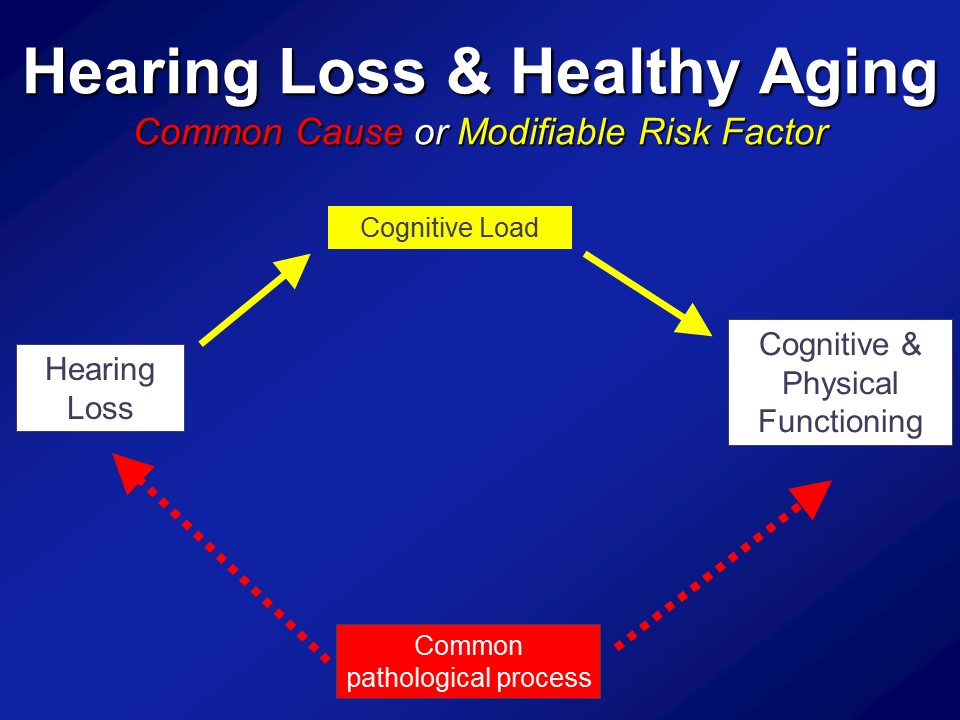

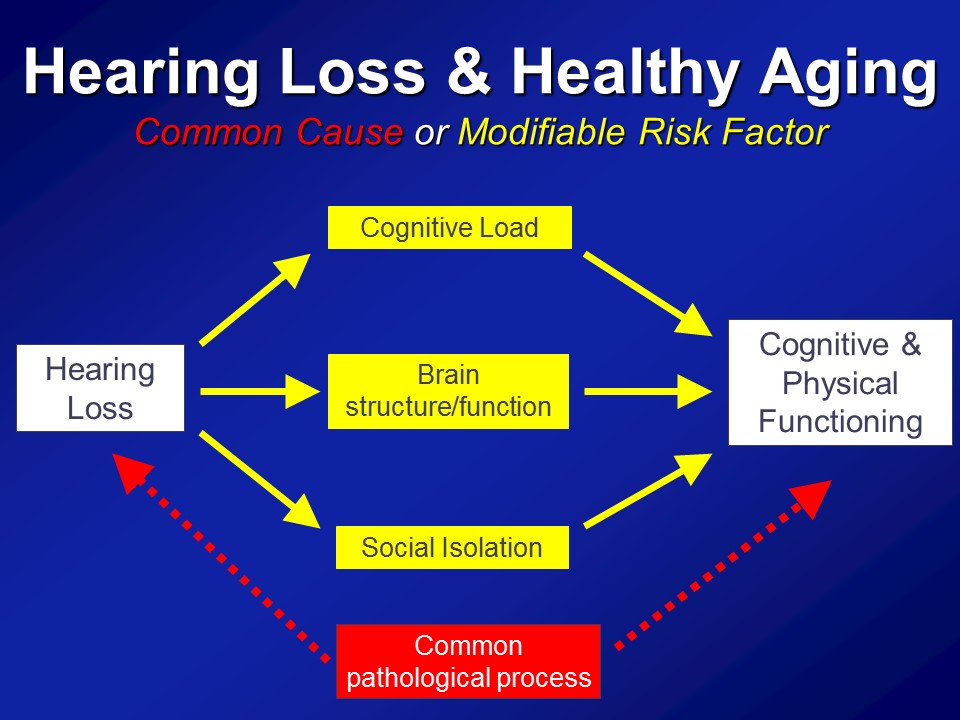

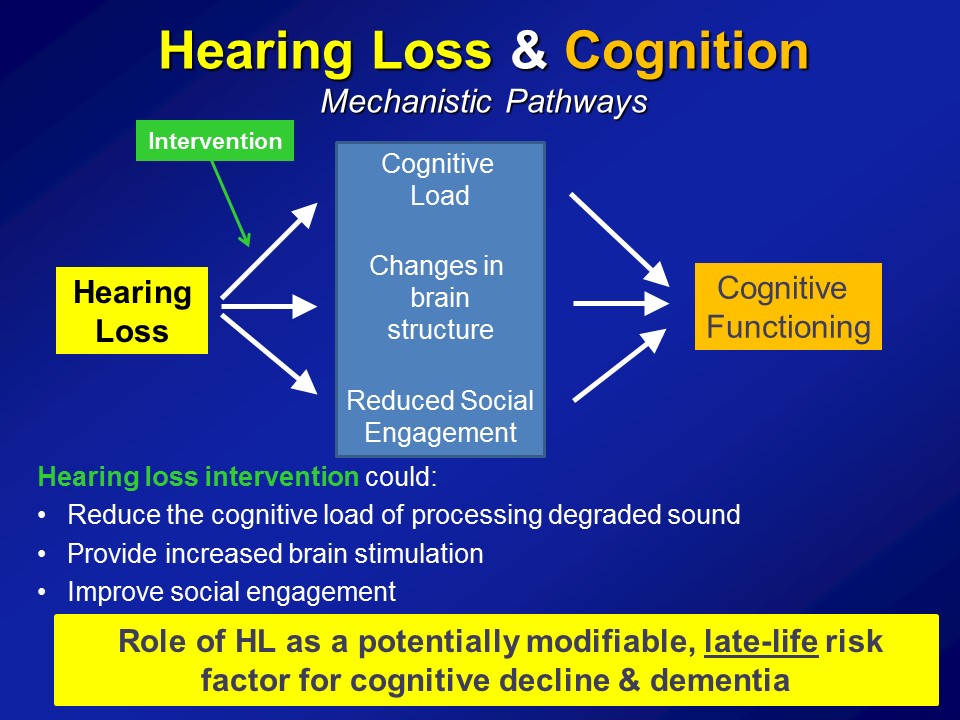

So in the end we think that over and above any type of purely correlational common cause pathway that there are likely mechanistic pathways in place to which hearing impairment could actually meaningfully affect the cognitive and physical function in older adults.

Cognition and Dementia

Research Studies

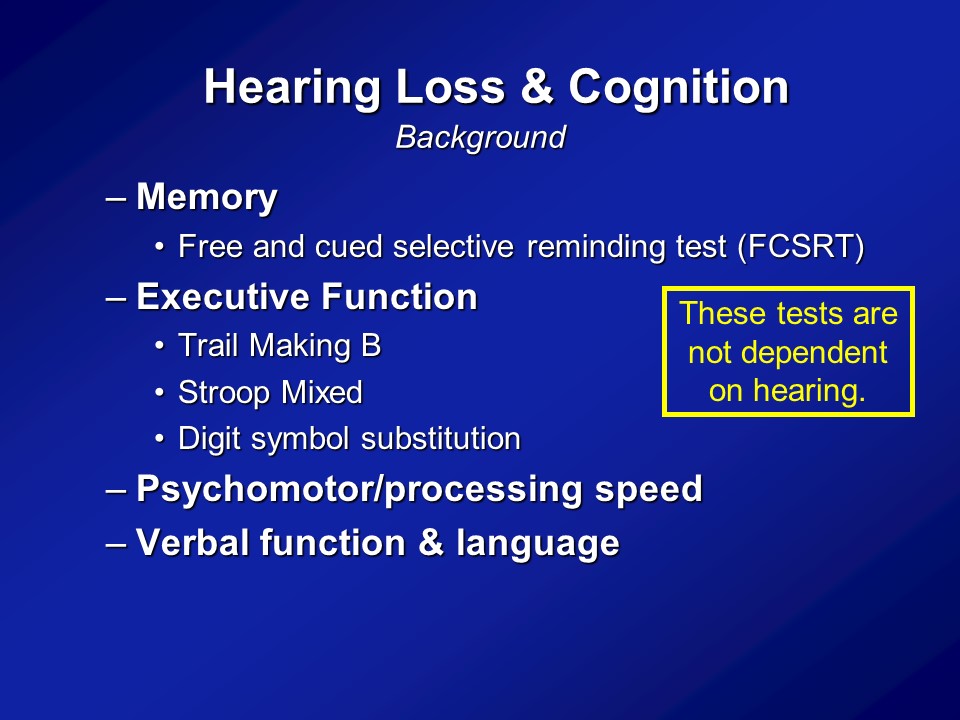

All right. So for this initial sort of phase of research, basically what we relied on is doing epidemiologic studies. So taking a large cohort or large groups of older adults who have been followed in the community just cross-sectionally at one time point or followed for many, many years. And basically asking these large cohorts of older adults recruited from the community who have their hearing measured, have their cognition measured, have their blood pressure measured, all these things. In these cohorts, do we see on average, is greater hearing loss, again measured by the better ears, pure-tone average or some pure-tone audiometry, is that a social poor cognitive scores even after controlling or adjusting or accounting for things like age, diabetes, smoking, hypertension.

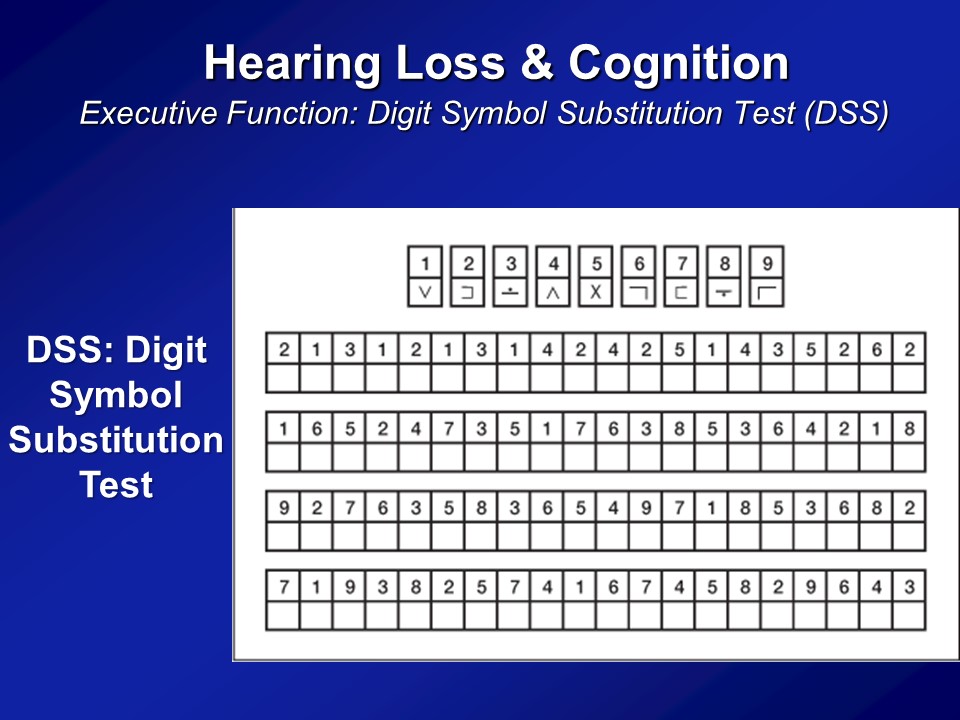

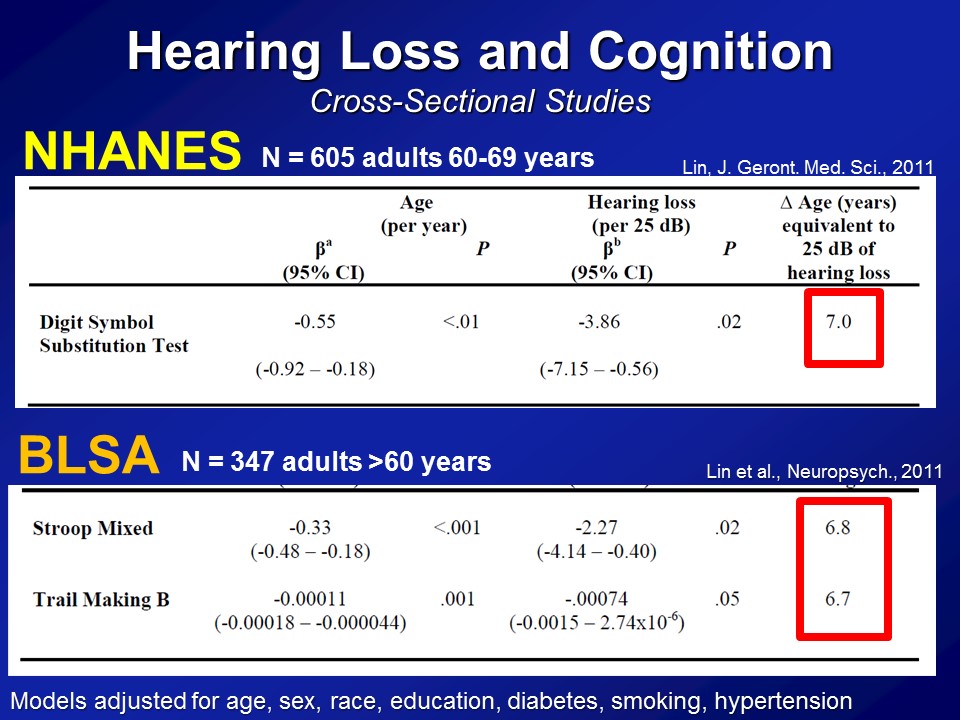

So some of the first analysis we did many years ago was looking just first at cross-sectional sites, one snapshot at one time point. And so on the first data we looked at was from NHANES, again the National Health Nutritional Examinations Surveys, basically a sample of the whole US population several thousand people at a time who have a whole bunch of things measured. All right, so this first analysis we did several years ago now looking only at adults. They’re 60s. This is– the range for hearing and cognition was both done, right. There are 600 adults on their 60s who had their hearing measured, had their cognition measured, and also where we adjusted for sort of everything on the bottom, their age, sex, race, education, diabetes, et cetera, et cetera, right. And what you see on average in these analyses is that for every difference in age of one year, you see that on average the DSS score has a lower score of about half a point. And that makes sense. The age goes up, your digit score should go down a little bit, the cognitive scores go down. If you look now at a shift in 25 decibels in the pure-tone now, basically for a normal to a mild hearing loss roughly, you see that’s associated about a 3.9 point score difference.

So what does that mean, how do you interpret that? In sort of the last column, if you look at the difference in age and years, that’s approximately equivalent to a 25-decibel difference with hearing and is associated with the cognition. It’s about seven years of aging, so it’s actually a very, very clinically meaningful fact as far as we can tell. Now importantly this is just one study, so the response that we got back then, well, Frank, this is interesting. But this is just one cross-sectional study, one exam, one test– I mean maybe, just a fluke, right.

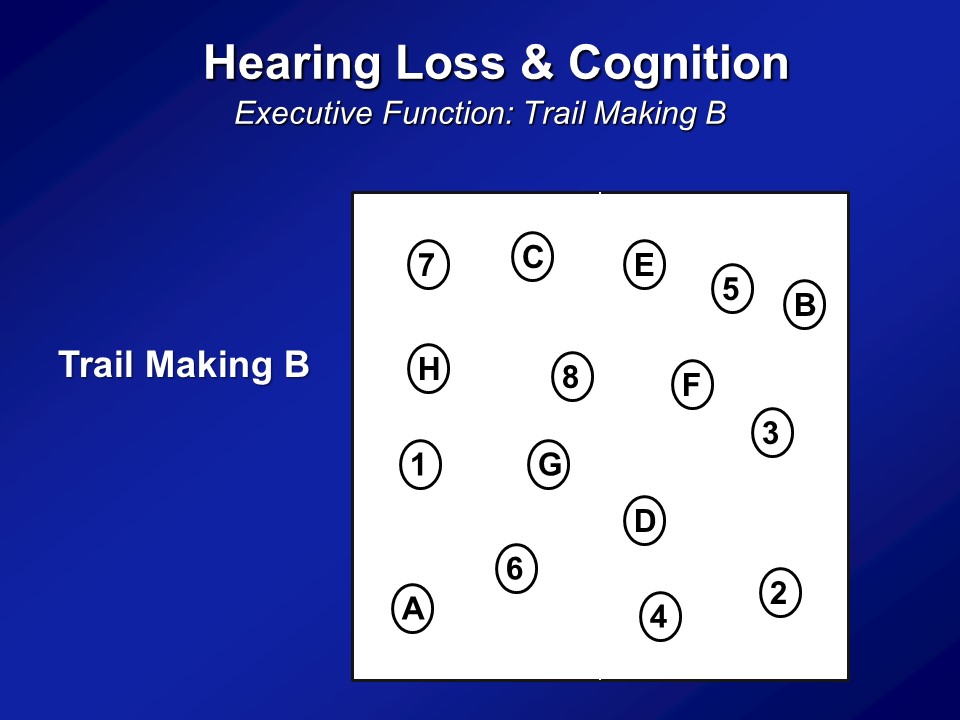

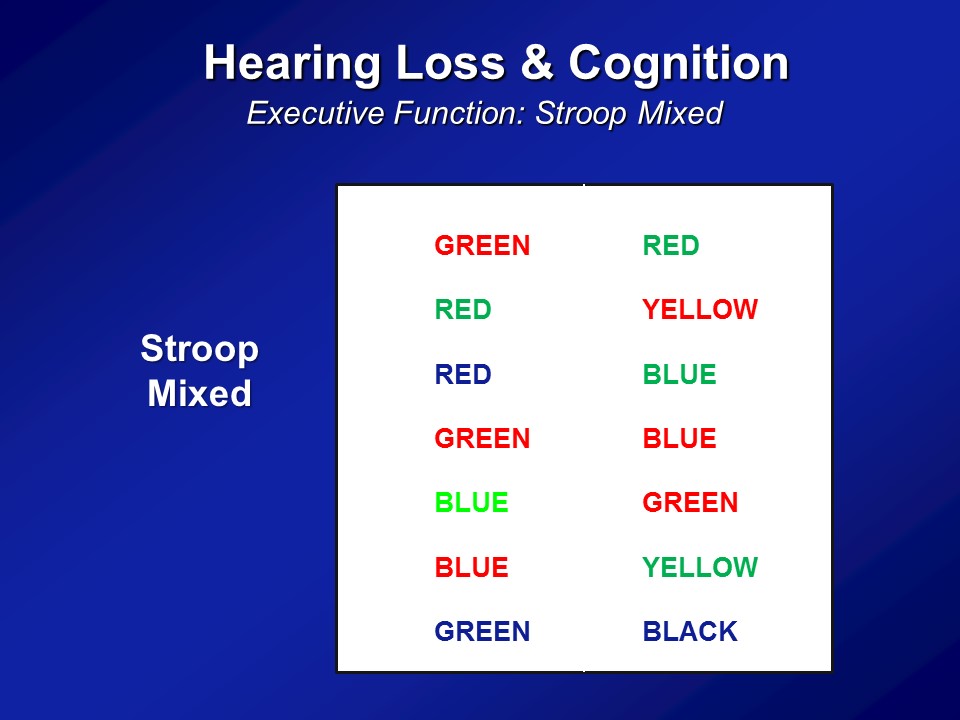

So we did the same analysis now in a completely independent dataset. This is something called the BLSA or the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. It’s a longstanding, longitudinal cohort of older adults followed at the National Institute on Aging, which is based in Baltimore, for this one center, where they’ve been following many, many hundred people for literally decades. And then we just have initial cross-sectional sample again, so 347 adults all older than 60, none of whom who have baseline in our analysis had dementia. We do the same analysis, but now we use two other cognitive tests. We use something called a Stroop Mixed, you saw before and the Trail Making test part B. This is the same analysis. We see that the association with difference in age in one year is this, with a 25 decibel hearing loss is this. And amazingly in many ways, across two completely independent datasets, three completely independent cognitive tests, is we’re roughly seeing the same magnitude of association here.

Here at this point several years ago, the response we still got was– Well, this is interesting. I mean, there’s been some previous works to adjusting this but this is just– This is cross-sectional data, right. You’re averaging across people. You’re measuring like a one time point, that’s it. You’re averaging assuming one person with a hearing loss would be behave like this if they had a hearing loss, et cetera. And the more convincing aspect is well, they’ll say, well, show me some more convincing data, by more convincing, I mean show me longitudinal data. Show me some data now where you’ve been following people for many, many years and you say within a given person, those with the greater hearing loss, did they actually have faster rates of decline over time.

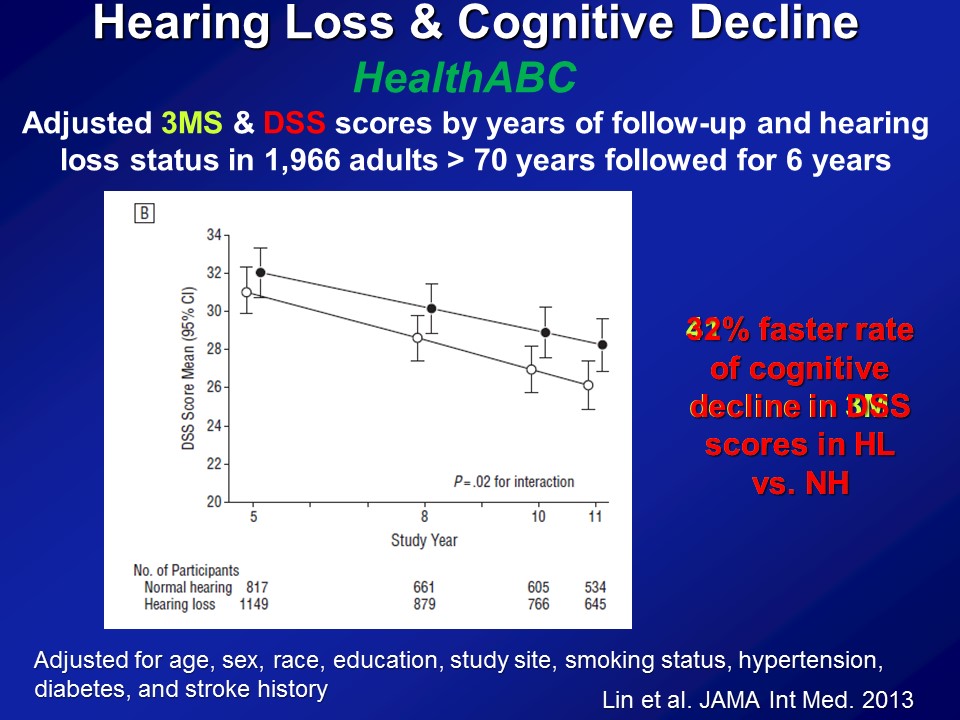

So this is the next set of analysis we did and we turn to another dataset at this point. This is called the HealthABC Study or the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study, also funded by the National Institute on Aging. About 2000 older adults followed now for about 15 years. Recruited from Memphis and Pittsburg just based on Medicare eligibility roles, brought in every year annually for blood pressure, measures of physical functioning, blood test, et cetera, et cetera, MRI scans. As well as coincidentally, fortunately, a measure of hearing and also very, very sensitive neurocognitive batteries. Some of the results right here. So this is about 2000 older adults all older than 70, none of whom who had dementia at baseline, followed now for about six years with a cognitive test on basically every two years.

And the summary data here again and again adjusted for everything in the bottom. This is just the summary results in the very end. If we look at a global measure of mental status, the three– the modified mini mental stages. So it does have a slight auditory component, the auditory verbal memory. But here the y-axis is — higher scores are better. And the x axis is time. And what– what you simply see is if you just break down hearing loss, no hearing loss as in better than 25 dBs versus worse than 25 dB, just a binary indicator of hearing. What you see is that at baseline is that people with hearing loss on average have lower cognitive scores, which makes sense with the previous data I showed you. Again it adjusts for everything down here. And more importantly what you see were about a six year period by the 40% faster rate of decline on the three MS over the six-year period.

Now if you do the same analysis now looking at the digit symbol test which is completely, again, no auditory stimuli as I showed you before, we see basically the same results. This is just one summary figure. The reason I say that because you can break down hearing loss, don’t keep it as just, you know, yes or no. You can treat it like continuous variable. You have some, mild, moderate, severe. And what you clearly see then is you do see this dose dependent effect — that the greater the severity of hearing loss up to a certain degree, the faster it declines. It’s just hard to show on the figure here so I’m not presenting those.

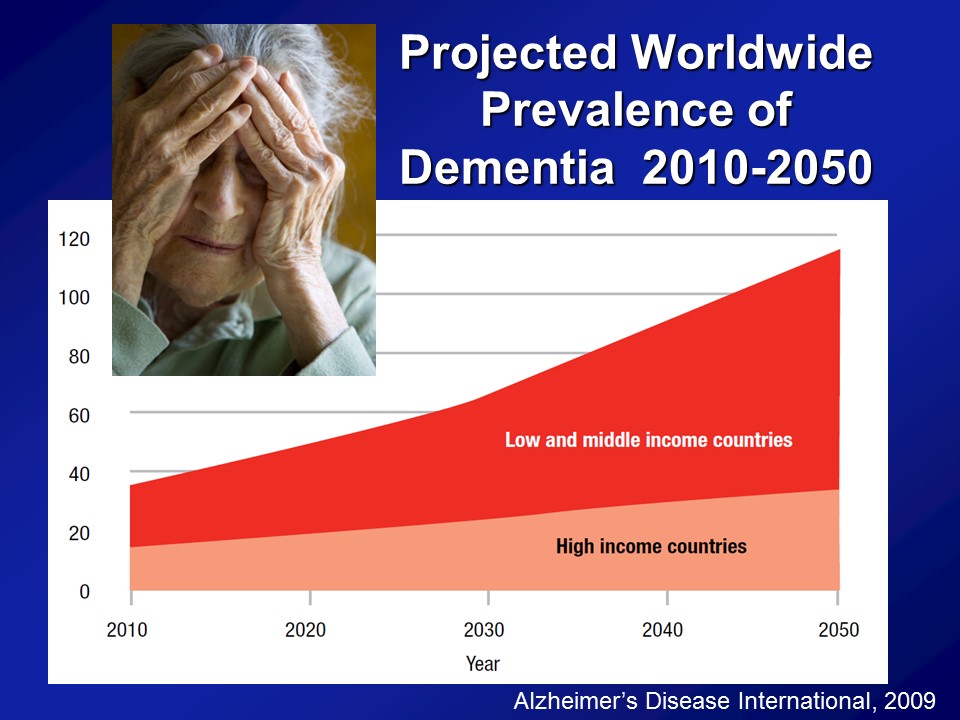

All right, so, you remember though I began this portion of talk talking about how– yes, cognition is important, but the bigger issue is dementia. It’s what you’ll more about today and just– There are many ways to define dementia. I’m just going to tell you in terms of from my perspective globally. I mean just a very useful pragmatic definition of dementia is that we– it’s not that you wake up one day and all of a sudden you have dementia. There’s a degree, the prodrome where you have cognitive impairment for many, many years possibly. The key thing is when you tip over dementia per se, many rules would say that’s roughly when it begins interfering with your daily activities. So that’s when you sort of are defined as having dementia. There are many, many different classification criteria for how you define dementia.

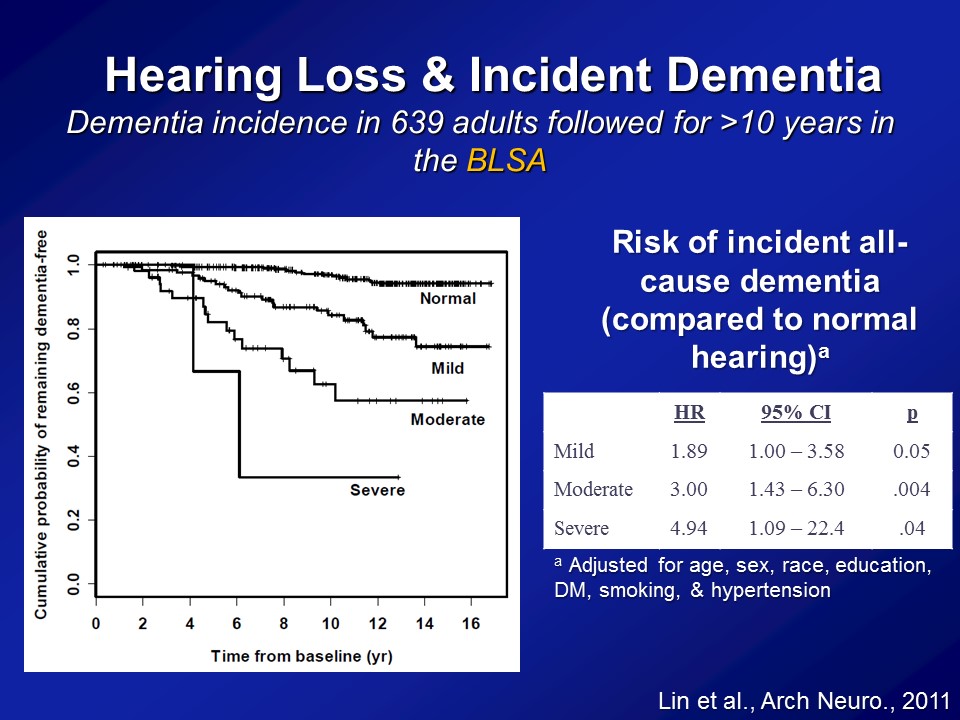

Importantly then, if we think hearing loss is associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline. Is it actually associated in a faster rate or a greater risk then of being diagnosed with dementia over time. So this is what we looked at. So this is data again from the BLSA, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. About 640 adults in their early to mid 90s who all had their hearing tested and were basically followed every year to two years thereafter up potentially until 2010 when we did the study basically. And importantly in the BLSA, when you diagnose with someone with dementia, it’s based on a very, very, adjudicated definition of dementia. It was based on the — it was called the NINCDS criteria back then, but this is based on a very adjudicated consensus basis definition of dementia back then. It wasn’t based on just one cognitive test for instance. It was based on a consensus definition of when someone developed dementia.

So, if we look at this raw data, this is just called a Kaplan-Meier plot. The y-axis is the percentage of people who remain dementia free. And the x-axis is basically a time from baseline. So obviously, at time zero, when people join the study per se as analytic cohort, no one had dementia. I mean, that’s why we include it in the study. And what you do, what you observe is you’re far more for the next 15, 16 years though, is that we see that progression or the progression to developing dementia being clearly related to the severity of your hearing loss at baseline. Now this is unadjusted though. We cannot– we haven’t adjusted yet for things like age, sex, diabetes and things like that. So when you apply these models now where you begin adjusting for those possible correlational factors, the possible confounding factors, we see a very, very similar relationship. That compared to people with normal hearing, the risk of developing incident, developing dementia all cause dementia is basically this called the hazard ratio or called risk ratio. For people with a mild, a moderate and severe hearing loss are roughly about twofold greater, threefold greater and almost about fivefold greater. I mean these are substantial risk ratios. We’re not talking a 5% increase in risk, like that. We’re talking theoretically, at least this one study at least, the 89% increased risk, the 200% increase, with a 400% increase of risk and I’m not going to show you– this study has been replicated now in another cohort based in the UK, only on men, though. That’s how the study was designed back then, but roughly showing exactly the same risk ratios as well. So very, very substantial risk ratios that we’re observing, not a small clinical effect per se.

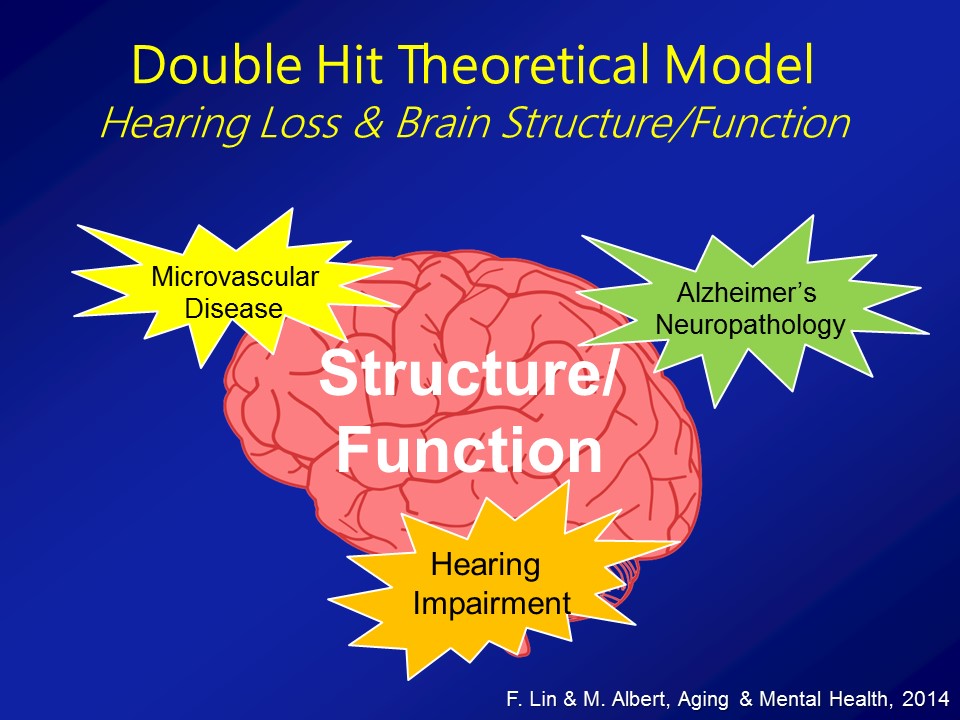

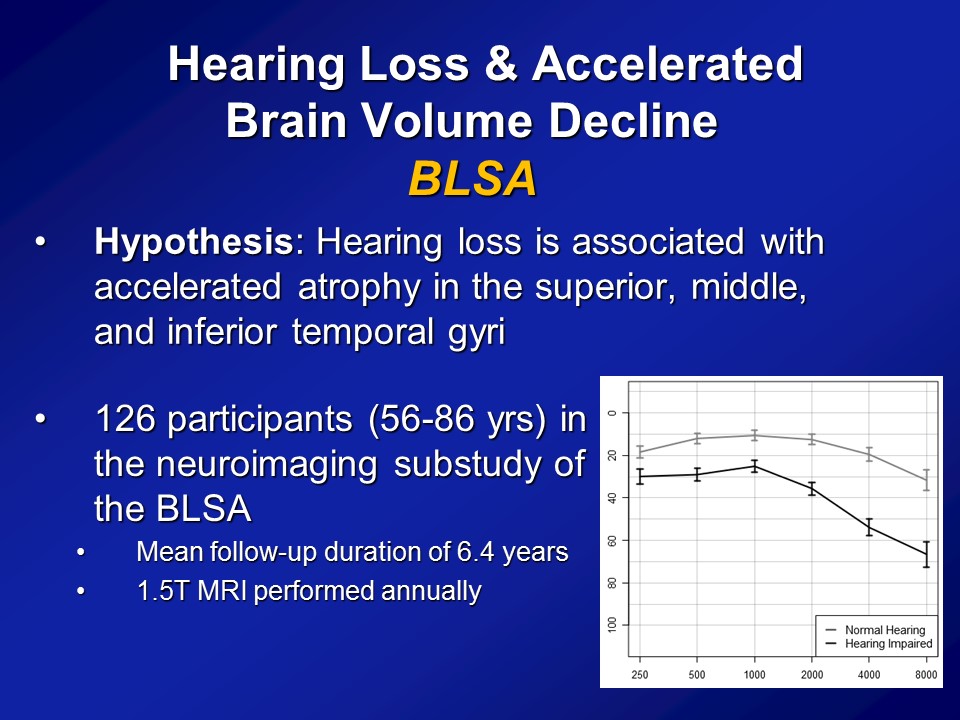

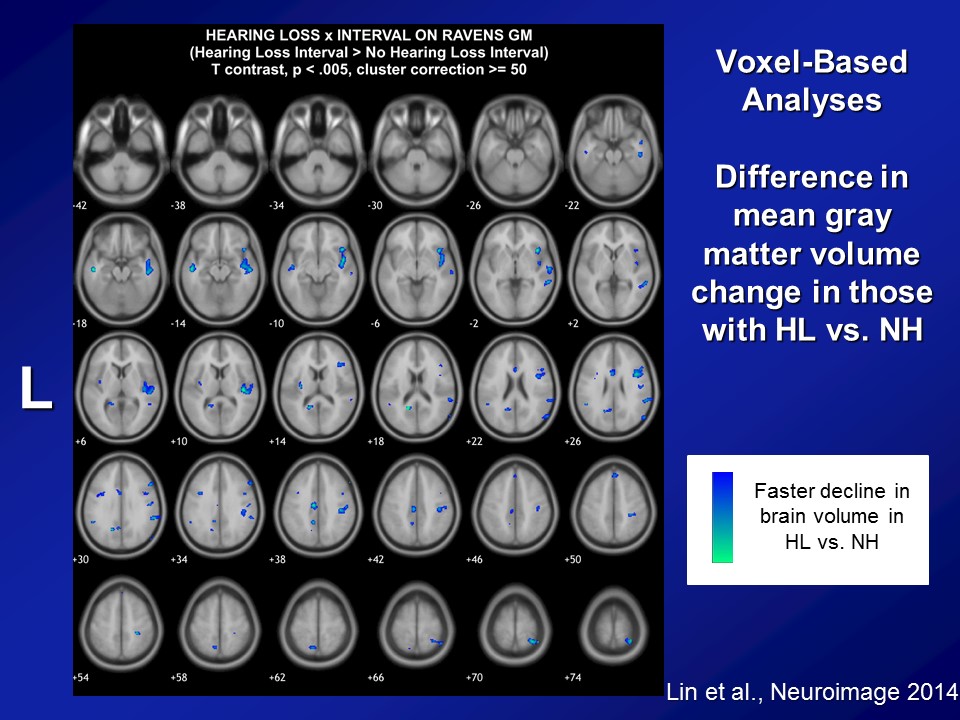

Now, importantly here though, when we published it several years ago though, the response that we got back then from many people was that yes, there clearly appears to be something there, that hearing loss does appear to be making a difference here. But what many people asked us still was well, “Do you have more objective evidence? Namely, if you think that hearing loss possibly affects diagnoses of cognition and a cognitive impairment, dementia, do you actually see hearing loss actually affecting the brain as well?” I mean a lot of times brain function follows with brain structure, not perfectly but to some degree. Do you actually see that hearing loss actually affects the brain. So our hypothesis back then when we did the study, again with the BLSA data, is that we a priori hypothesized that hearing loss is associated specifically with accelerated atrophy, brain tissue loss over the superior, the middle and the inferior temporal gyri, the lateral parts of the temporal lobe, which are not class of the parts of the brain which implicated in dementia. Those are more of the mesio or the more of the medial temporal lobe structures. But the reason why we hypothesize a priori is if you look at the literature as a whole, those parts of the lateral temporal lobe are the– they’re probably arguably, the very, very important areas for auditory association for how we process sound. So if we’re going to see atrophy anywhere, it should be namely in those areas, so the lateral temporal lobe.

In particular, what we did was we used data again from the BLSA. So from Susan Resnick, who’s at the BLSA, beginning in the early to mid 90s, this is remarkable back then and still remarkable to this day. They initiated a neuroimaging substudy. So they took about 130 people who are all the healthiest of the healthy. Basically, I think only a couple of them had diabetes. Some had hypertension but a very, very healthy subcohort. And enrolled them back in the mid 90s into a neuroimaging study where they basically came back every one to two years for a brain MRI. And this is fundamentally unique almost to this day still in terms of the degree to which they have longitudinal data. Most neuroimaging studies you see nowadays in the literature are still based on cross-sectional data. You have MRIs at one time, where you’ll have hearing at one time point at best and that’s it. What the BLSA is– has done, and still doing to this day, is a longitudinal cohort. So we had about 126 people back then who had their hearing measured who had MRI scans and basically had average follow-up at least 6 years of MRI scans done almost every one to two years basically up to about 12 or about 8 MRI scans. So offers tremendous sort of power in looking at individual change over time.

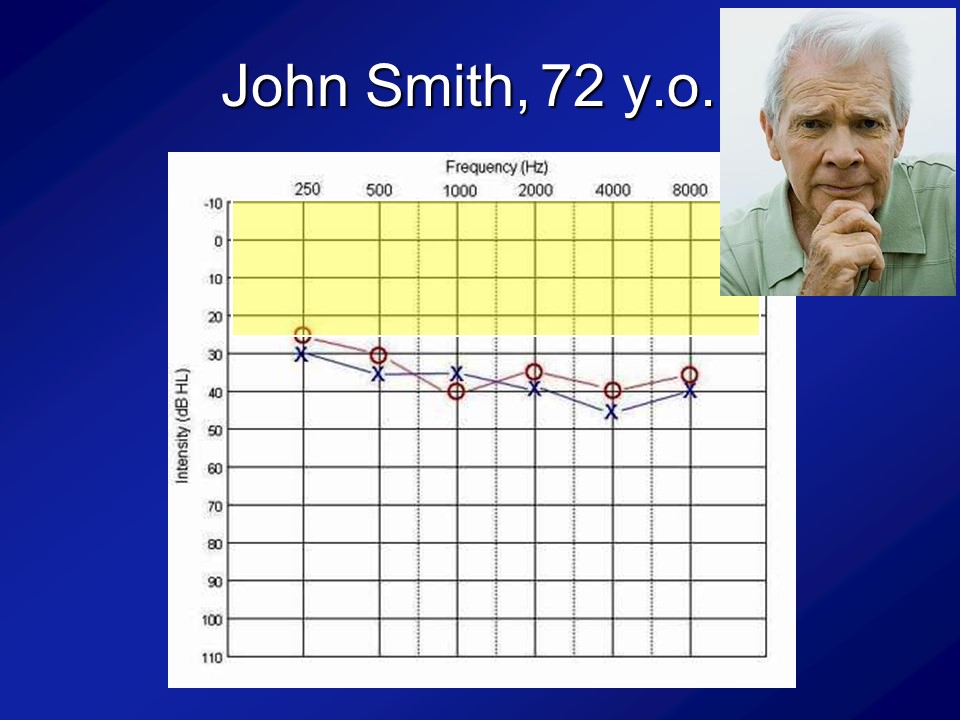

And importantly, if you look at this cohort of people, which I break out as the normal hearing and having hearing loss just make it easier because there weren’t that many people, is that what you see is that the audiograms of people are what you expect. I mean normal hearing up there and then this is the people with hearing loss. We’re not talking like profound hearing loss. We’re talking what we typically see in people who are 60, 70, 80, all right.

Audience Question

Just a quick question about the earlier work that you presented. So you presented three studies, all large groups, and you didn’t indicate there if they– if those folks were ever aided or if you were just assuming the less than 25%, and also just thinking about it’s likely the people with more hearing loss would be the people more likely to adopt to hearing aids.

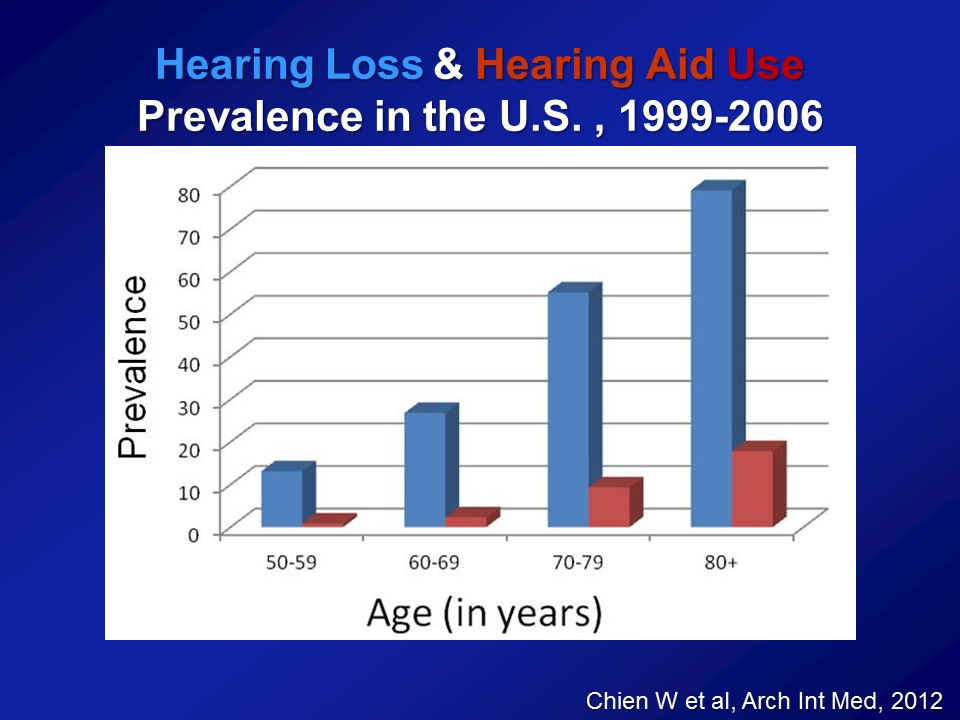

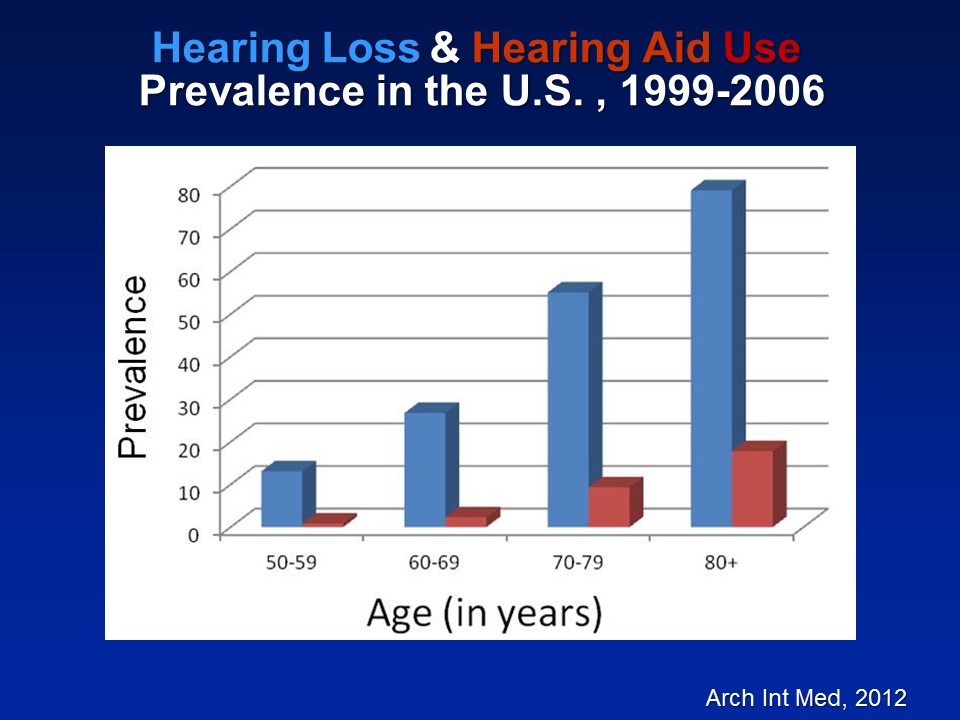

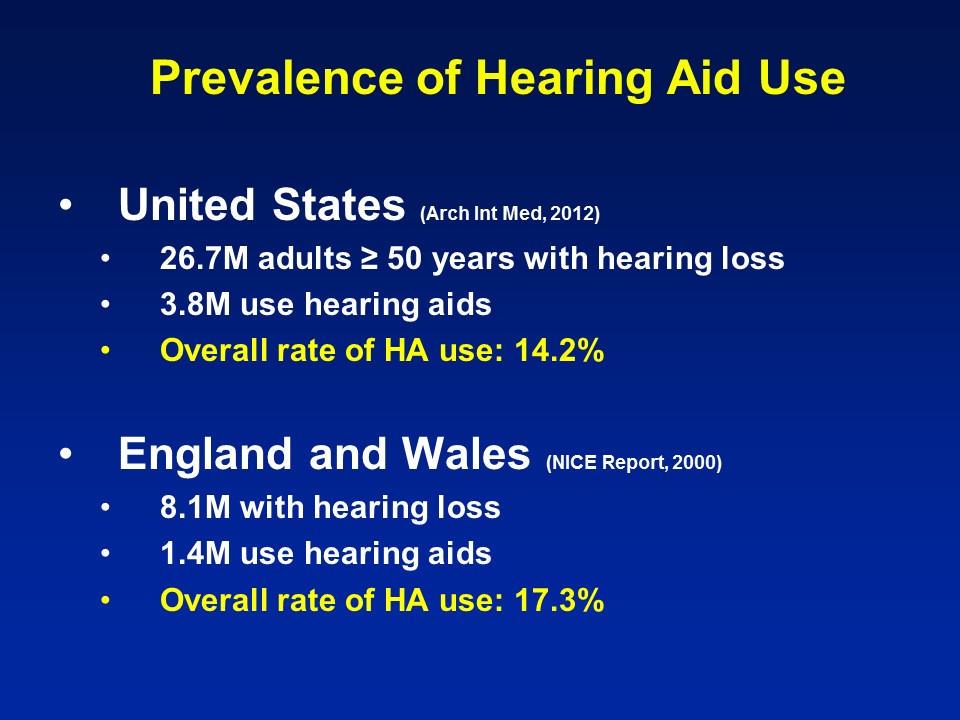

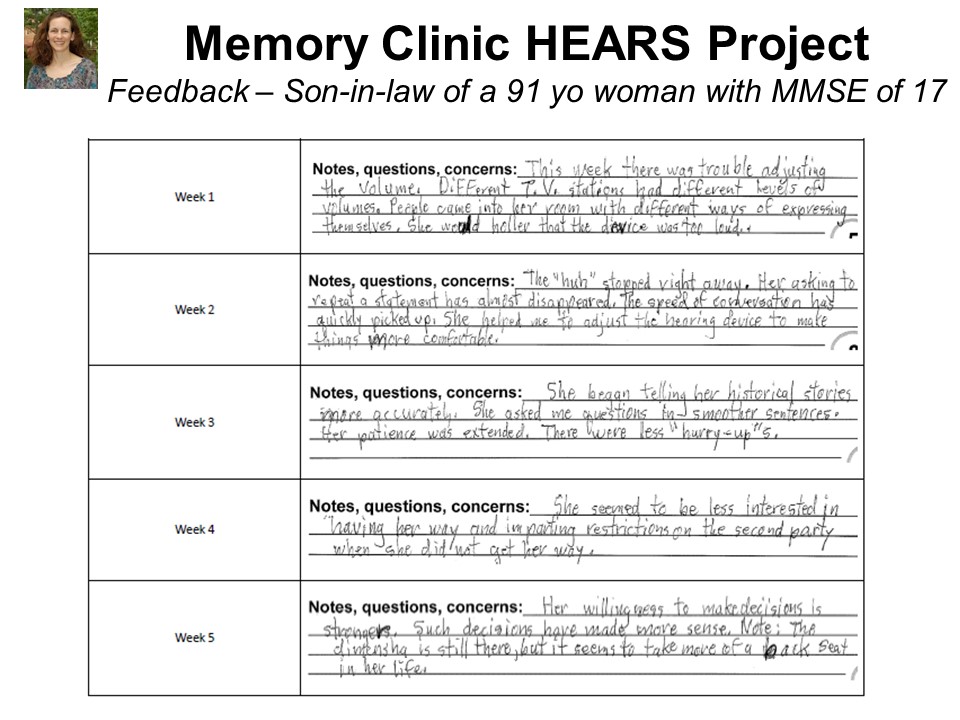

Great question. So, key question. So, based on all these other previous cohorts now as I’ve shown you, on average, about 20% of people who have had a hearing loss have actually used hearing aid. So when you do this analysis, I never emphasize, I never actually show it for this reason, is that if you actually tease out hearing aid use, you look at people who have hearing loss who use a hearing aid versus those who don’t. Do those people who just report of using hearing aid, do they do better? And they actually do, right. But I never show the data because you can’t– from my perspective, you can’t believe it. Because you can imagine among people of hearing loss, those who choose to get hearing aids versus those who don’t are fundamentally different.

And there are two cross competing biases, right. The one bias is clear, that people who choose to get hearing aids are the ones who are more affluent, the ones who are more health conscious, the ones who are more socially engaged to begin with. And that would all bias towards being a positive effect of hearing aids regardless of whether or not the hearing aids work or not. At the same time, with the cross-cutting bias though, that usual people with a more severe hearing loss are the ones who got treated, which was sort of biased, sort of against seeing that effect. You can tease that all you want in the way I still won’t believe it though. So I think there’s so many factors there that affected that I think it’s going to be very, very hard. You can tease out epidemiological, what we call propensity score analysis like that. And it’s being done right now. We’re trying to do it. But the fundamental question, and I think it will never be answered with observational data, because that’s these epidemiologic datasets. All they’re asking is that one question, do you use a hearing aid. Has nothing to do about whether it was properly fit, how many years you were wearing it? Are you using in one ear or two ears? Are you using it for most of the day or not in a day? Do you have overall good communicative strategies? So there’s so many other little nuances there that’ll never be teased apart from observational data though. So that’s why I said this has not been answered. And I think the thing that’s really needed to definitively answer this is a clinical trial. Where you randomize that baseline, people get treated versus don’t treated. Yeah.

Audience Question

This question is somewhat related, but it’s addressing what you said here with the randomized clinical trial. I know that randomized clinical trial is really important in this sense, but it is extremely difficult to do– also in public health, it has to be population-based. And randomized clinical trial tends to be more clinically centered. This is the same problem on the other end of the spectrum, the universal newborn hearing screening. When the US Preventative Task Force actually judged whether newborn hearing screening is worthwhile to do, and they actually downgrade to grade B. Because there’s no randomized clinical trial. Even until now, it is extremely difficult to pull off a randomized clinical trial in the other spectrum. So in a sense of that, how do you get around this for the adult population?

So, give me two slides.

I think what she was getting at fundamentally is sometimes clinical trials are really, really hard to do. Even beyond, I think what you touched on briefly too is that, clinical trials show efficacy — if you did everything perfectly in a clinic-based setting. But we’re still not been getting it at effectiveness in terms of broad-based real populations, audiologists and the field, things like that. Two different questions, usually they start with efficacy and they go to effectiveness hopefully, but all right.

What is the impact of treating ARHL on older adults?

ACHIEVE Healthy Aging Clinical Trial

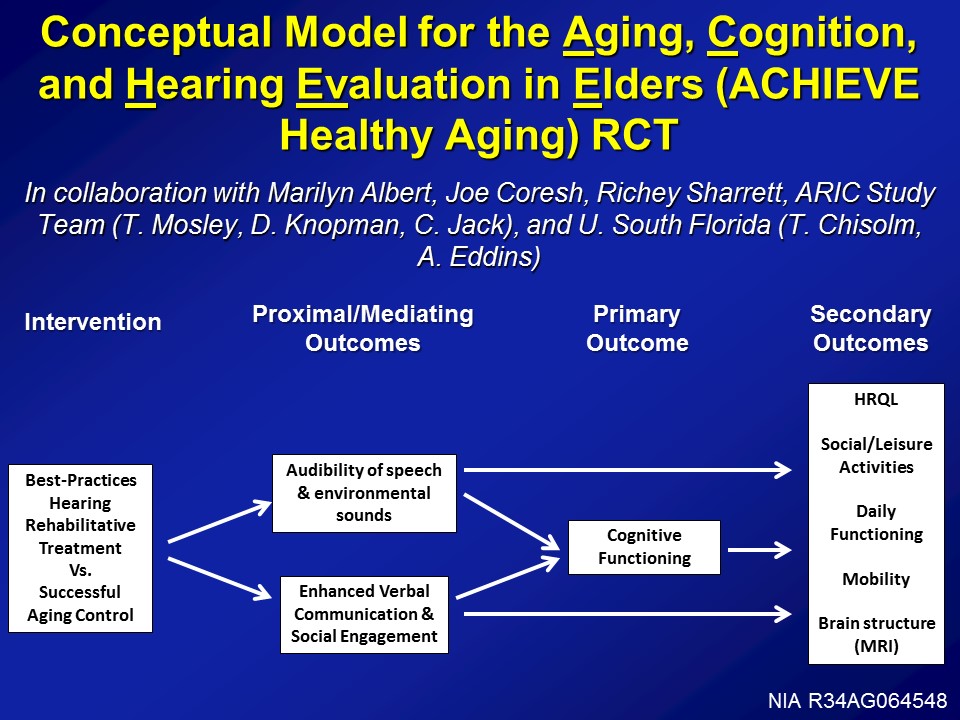

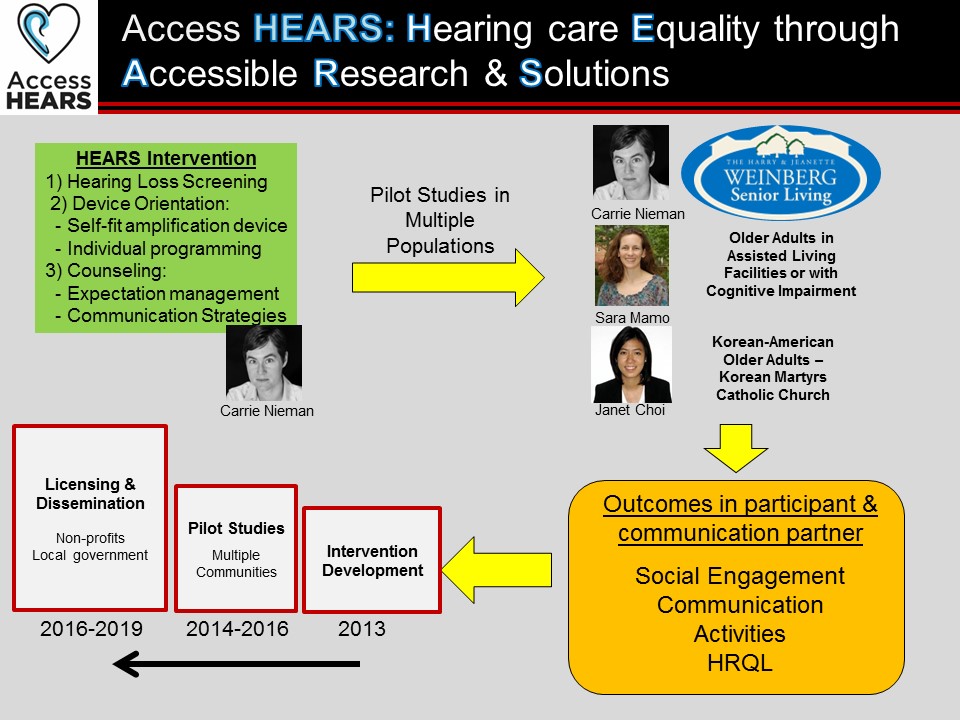

So with that in mind, to your point, well, what about clinical trial? So this is where we’re going right now. So we have the initial phase of funding from the National Institute on Aging to develop this exact clinical trial. So, conceptually it’s called the ACHIEVE Trial, that Aging, Cognition, and Hearing Evaluation in Elders or the ACIEVE Healthy Aging Trial. And it’s being done in collaboration with a lot of people across the US.

The design of the study, it looks like this, is that at baseline we’re taking 70 to 84-year-old adults with mild to moderate hearing loss with no cognitive impairment, randomizing at baseline to basically best practices hearing rehabilitation as defined, and being manualized by Terry Chisolm’s groups at University of South Florida. So basically hearing treatment as it should be done, counseling, sensory management, fitting of devices, education, not really auditory training but ACE therapy, so Louise Hickson’s work looking at just communicative strategies, things like that. We randomize at baseline versus a successful agent control, which is basically an established program at the University of Pittsburgh, which is basically these individual instructor or clinician one-on-one interactions with– It’s been going over healthy agent topics, nutrition, diet, exercise, things like that. Which has been shown to– seniors, older adults actually like this a lot. So, randomized at baseline to one of these interventions.

Proximal outcomes looking at things like audibility speech, environmental sounds obviously, as well as communication, social engagement, but really being powered over a three to five year period looking at rates of cognitive decline, can we actually reduce the rate of cognitive decline, possibly reduce the risk of dementia, really powering up cognitive decline in this cohort though. As well as looking at a host of secondary outcome measures, looking at things like mobility, daily functioning, brain MRI hopefully as well if we can get funded, as well as social activities.

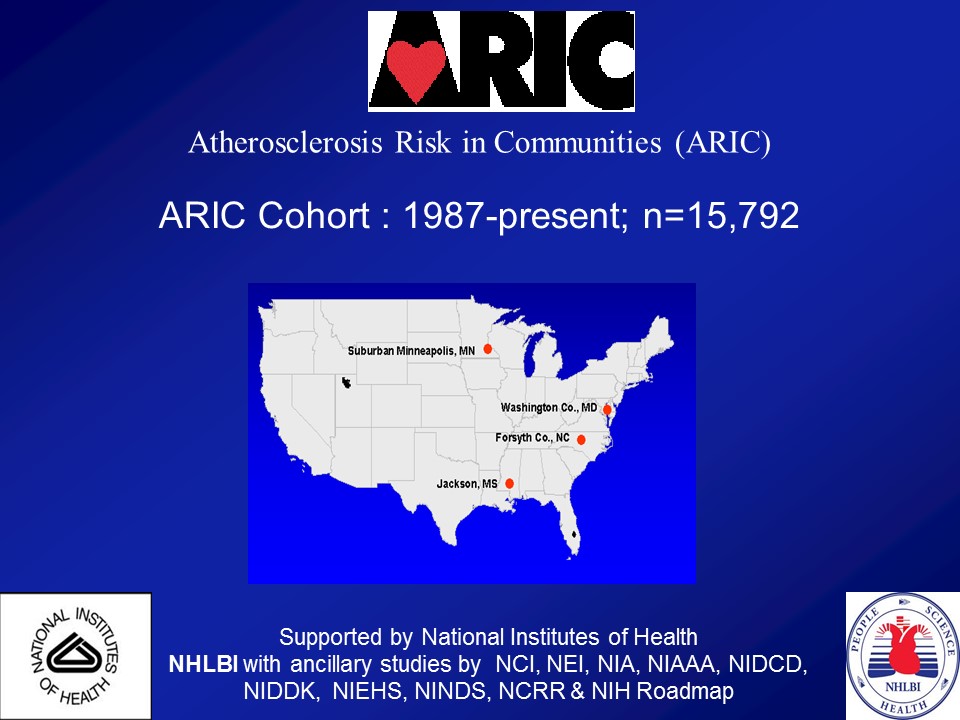

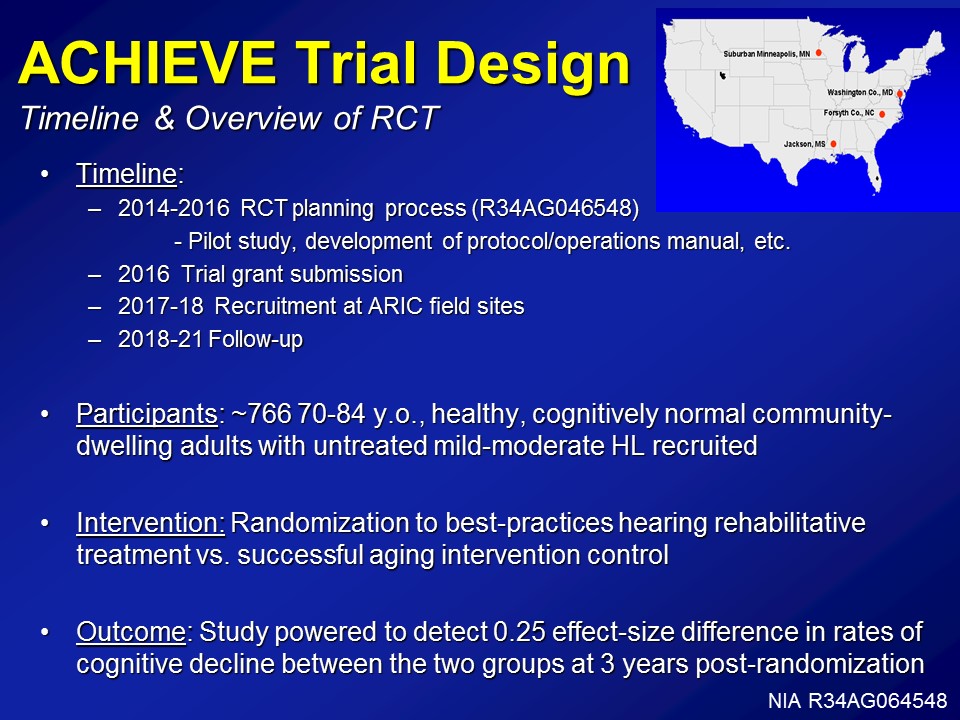

Now, importantly this trial, much to your point: how do you operationalize in such a trial like this? So this is where efficient science is key and collaboration is key. So there is a study called the ARIC study, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities studies. A 16,000 person cohort study, began in 1987 at four different centers across the United States. So people back then were 40 to 60-years-old. And now– they’ve been followed now on average about five visits over the last 25 years, right. Where every year, every five years on average they have been coming back for neurocognitive batteries and measure vascular blood pressure, a whole bunch of things. The initial phase of the study was being powered to really look at midlife vascular disease and how it is associated with later life cardiovascular events. And they have — I think have been 1300 papers published as a cohort already. So what we’ve been doing over the last few years now is teaming up with the ARIC cohort, is our clinical trial will be nested within the existing ARIC cohort. So we’re taking a sub-sample of their– Because that there are about 6000 people who are still surviving, taking a sub-sample of those and doing a clinical trial in these folks. So, operationalize across these four community-based cohorts across the United States going forward.

Now, the reason why this is important and this is key, is because if you’d recruited a complete de novo cohort, you could, but then you have four measures, right. You have their baseline measure of cognition, and hearing obviously, too. And then you have annually, their measure of cognition at years one, two and three. So can you look at these individual trajectories over time, and what you hope to see obviously, the people with treated hearing loss, it’s flatter than people who have– don’t get treated maybe it’s a little more steep. That’s where you hypothesize. But you’re fundamentally basing that change though in basically essentially four data points, the baseline and years one, two and three. In ARIC, the beautiful thing about ARIC though, is people have been followed for 25 years. So we know their preceding 25-year trajectory of cognitive function to begin with. So it makes it far more powerful looking for an inflection point. So basically looking at, 25 years goes like this, do we change the inflection point for what they’re doing now, once we began addressing hearing loss. So it makes for a very, very efficient science here. Not only in terms of logistically in terms of operationalizing the study across four different sites and like things like that, but more importantly from a scientific perspective too, it makes it far more efficient and far more powerful as well.

So just a brief overall view of what this RCT is doing right now. For the last year and a half now– or, last year I guess. We’ve been funded under, it’s a weird grant. It’s called– It’s a Clinical Trial Planning Grant process from NIA, which basically just allows us to do the development of protocols, operational manuals, the pilots have to be funded actually by another grant though. But just operationalizing the whole process takes about literally about a year and a half, two years. Next year, we’ll submit for the complete trial grant, which is a bit of a monster. From there about two years recruitment and from there about three to four years of follow-up.

Right now, it’s being powered about 766 people, 70 to 84 years old. Again, healthy cognitive and normal community-based sample. Intervention, again, is the best practice here in rehab versus a successful agent control group. And finally, we’re being powered to about a 0.25 effect size in rates of cognitive decline over time.

So this, I get very excited about this in many ways, but it’s for me it’s also a little bit daunting in a way, right. Because what you’re fundamentally doing is a primary prevention trial for cognitive decline. Which means the earliest, well, results from a study like this assuming it gets funded in the first round next year, which is hopeful but you never know at NIH. The earliest of results is about 2021. So this takes a long, long time actually. And the reason for that again is because it’s not so much when we treat someone’s hearing loss we’re going to improve their cognition, I think. But it’s not looking for improvement, we’re looking for whether stem the decline. By definition, you have got to follow everyone for several years then. All right.

How can ARHL be effectively addressed in the community?

Barriers to Hearing Health Care

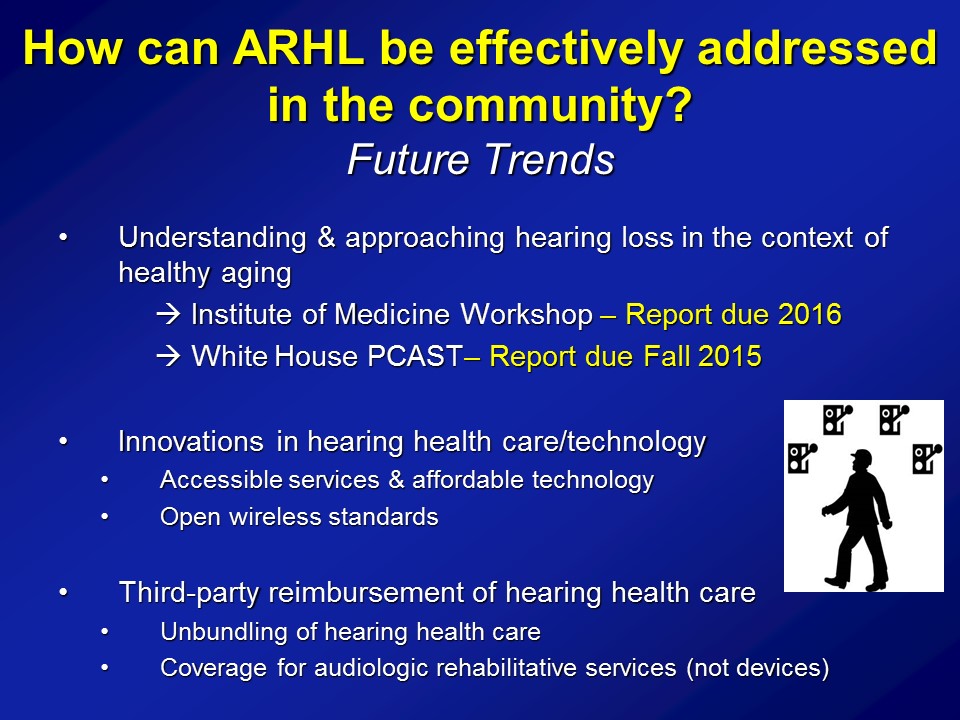

Future Trends

So on a more positive note though, I think this is beginning to happen. And importantly, I think there are some very rapidly– I would say future sort of current trends right now that are rapidly evolving. And probably one of the most important ones is actually, if you ask me is that it’s we’re increasingly understanding and approaching hearing loss within this context of healthy aging public health. And what I mean by that is that hearing loss in and of itself, by itself is not interesting. It’s a usual process of aging. It’s like hidden disability, yada, yada, yada, it’s not interesting. But if you understand hearing loss in the context of why it matters for the big important things is when it becomes really, really interesting. And fortunately, I think this is beginning to be recognized at the national level, right.

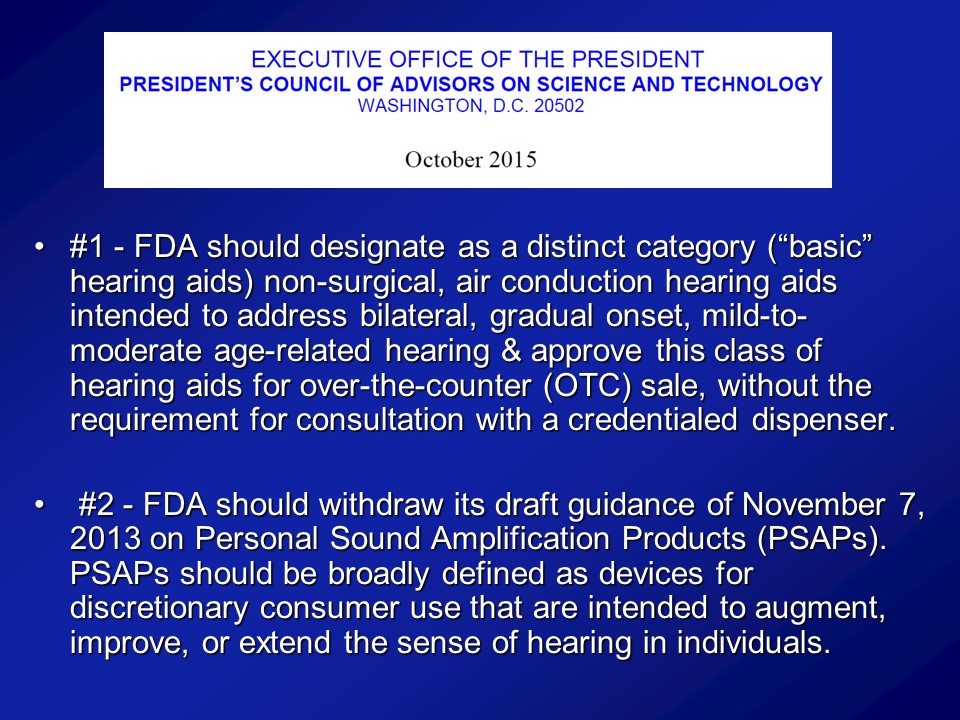

So, one of the biggest one, this just came out three weeks ago now. The White House Conference on Aging and the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, PCAST report, how many of you guys have heard of this? That’s it. All right. So– right so we’ll give a– oh we get this– There’s something, if you have anything remotely to do with hearing loss in adults, this is something you have to know about this. This is– this is fundamentally at the national level about as top-down as you can get. So basically what happened in– in July of 2015, just four months ago now is the White House had their– who’s heard of the Conference on Aging? Few of you guys, all right, that’s not bad. All right. So the White House has a Conference on Aging about every decade, roughly on average.

I think this is the fifth conference on aging they’ve had since the 1950s, and these are big deals, I mean this is a– President Obama attends, this is a big conference on aging, which fundamentally address what are the issues, barriers to older Americans. What can we do to reduce cost, help them integrate, et cetera, et cetera. These for the last 50 years, and we have them every decade, they lead to big things. They have led to the social security. They have led to Medicare. These have a major policy which have come directly from White House Conference on Aging. So one of the sub-themes that came out of the White House Conference on Aging this past July was around the theme of technology and aging. What can we do to harness technology to allow older adults to age in place, to increase our productivity, to increase their participation in society? It’s a very, very broad topic for technology as a whole.

Questions and Discussion

Audience Question

Hi. My name is Fatima. That was a great talk. I have two questions actually. The first one is, what is the best practice for including or excluding people with dementia who also have hearing loss when we do research related to communication. I was wondering, like, whether we should include those who only wear hearing aids or some kind of hearing amplification, or we can actually include those with mild, moderate hearing loss who are not being treated?

Audience Question

So secondly with your ACHIEVE project, you were saying that one group is getting the best treatment for hearing aids, and the other one is getting successful aging which might not be related to fitting hearing aids and so forth. So in the after you collect all the data, will both groups receive both kinds of treatment?

Audience Question

My name is Aaron Roman. You talked about changes in brain density and neural changes. So you said in your study you looked at changes to superior, inferior, medial, temporal gyri. Do you notice any larger scale changes such as associations with the prefrontal cortex and pre-motor cortex?

Audience Question

Hi, I’m Julie Dalmasso. For the cognitive assessments, you mentioned that they don’t need the verbal audibility to complete the tasks, but how are the participants given the instruction, when those still have to come from a verbal nature?

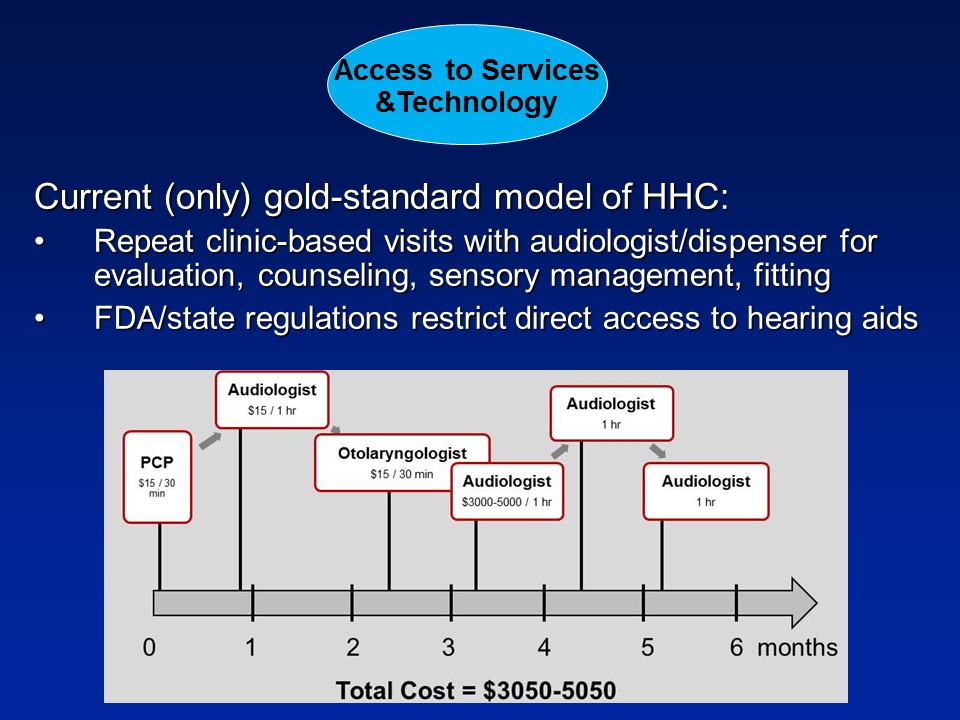

Audience Comment

Barbara Cone, VP for Academic Affairs and Audiology. Thanks, Frank. I have a comment first and then a question. And my first comment is about the gold standard for treatment, which you defined as: audiologist, $3000 or $4000 hearing aids. I would just like to say that I think that as a result of the FDA regulations and some of the decisions made by the medical community over the last 30 years, we have been hamstrung by that to only provide that kind of care. So I think with this call for a decrease in regulation, we as audiologists can come up with better models. But we have been hamstrung by these regulations.

Yeah. No, I completely agree.

Barbara Cone:

But I do have a question for you. I’m so glad that you brought up the the example of cardiovascular intervention that is now the norm. And that is with the complex condition like cardiovascular disease or even diabetes, would you recommend over-the-counter treatment for that? Because it seems to me that hearing loss is also a very complex disease or condition, and we’re recommending over-the-counter treatments now? Would you recommend over-the-counter treatments for other health care conditions that do impact dementia like cardiovascular disease or dementia?

Frank Lin:

I mean, a lot of the cardiovascular– I mean these medicines are great. But even beyond that though, exercise, things like that are I guess over-the-counter as far as you can say it. I mean I think it– it all depends on the system you’re talking about. I mean, the analogy that PCAST used was issue of readers, for vision and things like that, you get prescription spectacles where you get magnifying spectacles.

Barbara Cone:

Yes. But would you manage cardiovascular disease completely in the hands of a person who could buy an over-the-counter medication and not be– and not have the opportunity to consult with a qualified health care provider?

I think that we have to temper some of what we’re saying about over-the-counter treatments with the realization, this is a complex health condition and there will be a considerable need for a person with such a complex condition to be able to be seen by an appropriate healthcare provider which I think is the audiologist.

Frank Lin:

I’ll qualify that though. It can be complex. It doesn’t always have to be complex. So I think the key thing there is that there are multiple different components of what we call hearing healthcare screening, diagnosis, counseling, training use of the device, ALDs and there are always different components of it. And I would argue for any given person, they may only need one or two, or they may need all but I think it varies from individual, individual. And yet, we don’t give that option right now, more importantly, yeah.

Audience Question

[Margaret Rogers] I had a question, and that concerns, will this work for kids as well as adults?

.

Oh no, no– No, no, I think that’s a whole different ball of wax. No, completely. I mean the PCAST report is only written for adults– actually older adults even. IOM report were limiting purely to adults too. Pediatric hearing loss is a whole another beast where that has to be medically evaluated. That’s completely different though. Yeah. No, I agree. Yeah.

Margaret Rogers:

And of course there are many of us that are worried that parents in the future will just slap whatever they get at CVS or Walgreens onto their kids. And do you have any sense of how these governmental and the IOM agencies are going to manage that risk, just how to manage that risk?

Frank Lin:

Can’t fully probably comment at this point, but it is something that’s come up obviously, the topic, yeah. But this– Let me say, that’s not unique to hearing devices. You could apply almost any type of over-the-counter where you could do the same thing, let us put it this way. Yeah.

Audience Question

My name is Jan [unsure], I’m from Nebraska, and I’m interested in this model looking at farmers and actually even starting with teenage children who are exposed to noise and so they are developing noise and just hearing loss over their life span. And seeing if maybe these cognitive defects or that deficits start earlier in patients like that. Do you think that’s something interesting to pursue?

Audience Question

I’m Evy Webbing and I am a North Carolina Central graduate student. Going off of that question, do you know if there are any studies that have been done studying early onset hearing loss, and then later developing or cognitive decline?

Audience Comment

Harvey Dillon. Just a comment on a comment that came up earlier about there not being any evidence about early intervention in kids. There actually is. In Australia we had the opportunity, when had some states had newborn screening and others didn’t. But no matter what age they found it, they all got treated the same way by the national organization, so we jumped in and started a longitudinal study. Those kids are now 9 to 12 years old. We recruited them when they were babies or up to age 2, and there’s a huge difference between the ones who got the early intervention and those who did not. I just wanted to correct that record. There’s a special issue of the International Journal of Audiology from earlier this year. It’s got a bunch of papers that’s the age 3 data. And the age 5 data we’re working on at the moment. But Teresa Ching is the person leading the study.

Audience Question

I was interested, over a 40-year period or whatever, these increases with age of hearing loss have remained about the same. But now we have a generation of people who grew up on rock music and, you know, iPods in their ears and so forth. And they are now becoming the aging group. Do you have any hint that that may change the profile of hearing loss increases?

Audience Question

I’m Rosemary McKnight from CU Boulder. Do you think there’ll be any recommendations forthcoming about a hearing screening program? At what age to start offering routine screenings as part of primary healthcare?

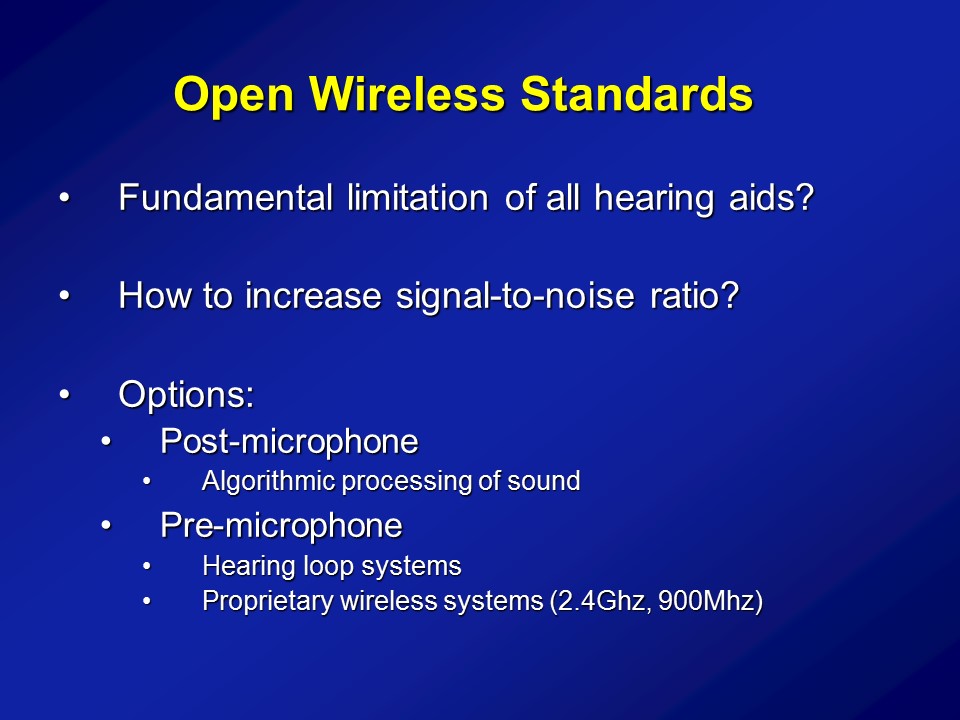

Audience Comment

Hi, I’m Nancy Nelson from Indiana University, and I just have a comment about you just referenced Sharon Kujawa’s work. And just thinking about this public health model and how it might work, and how consumers might get more direct access either through telepractice or through the telephone hearing tests or a variety of ways that they can be tested. That work makes me think as an audiologist that the pure-tone audiogram probably isn’t going to continue to be the end all and be all. And so I would just caution that as we move forward with these really large scale kinds of initiatives that we think carefully about adding some additional kinds of testing, maybe speech and noise testing might be the easiest to implement.

Audience Question

I work for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. So I’m rare in a sense the audiologist working in a public health agency. My question is, I think this is the broad question, are you also going towards the direction of policy study in whatever you’re doing? Are you going to integrate a policy angle into it?

So– I can’t do everything. But I would say, the closest I guess personally for me that I have been very interested in this is, yes the– You can do all the research in the world, let’s face it, and you can make– if you’ll make a little difference. So I mean that’s been a lot of my work through IOM, so I was– I co-chair the panel last year of IOM on that, that’s why that led to this consensus study.

So I think policy will hopefully evolve very quickly from PCAST and when the IOM come out next year, we don’t know what they’re going to say yet, obviously, or we’re going to say yet. But that I think will be where policy evolves from, very quickly, hopefully. Those are the– those are only initiatives I know– the big initiatives going on right now. Within the VA, obviously, VA is a whole another– and, you know, Lucille Beck and I mean, there– they have been long aware of these issues too. But, I mean that’s– I can say personally is what I’m doing at least. But beyond that, the policy piece looking at I would say broader questions of demonstration projects within CMS, within Medicare for different types of therapies for treating hearing loss and what are the long-term benefits. I mean those, I guess, were policy issues, more research which no one is really doing yet unfortunately.

Audience Question

Then my next question is somewhat related with the hearing aid legislation. Now in the newborn hearing population, this is what CDC is charged to at the other spectrum of the world. All right, in the sense of what we have been noticing in the newborn hearing screening with regarding hearing aid use is that legislation to actually cover hearing aid — it seems to us you have to be fighting a state by state, beginning at the state law. It is extremely hard from the federal level to fight that war. It’s been very successful in the newborn population to fight state by state, lots of states have passed coverage for hearing aids and some of them actually extended to adults. So do you foresee that this may be replicated in the adult population fighting it from the state to state level? And how much of the PCAST is you think that it’s going to influence the state legislation and politics?

I don’t know.

Margaret Rogers:

Well, you have really shared so much with us today and it is wonderful to get this data and to get this look at where we’re going with the future. I know that all of us have been thinking a lot about our roles in the future healthcare system. This is very helpful and I think very clear and well thought out. So, thank you, Dr. Lin.