The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

We’re going to tell you a little bit about what happens once your grant is submitted to NIH — this is specifically about NIH reviews.

There are two sides to this grant writing and reviewing process. Before your grant goes in, you’re going to be working with a program officer, who will be guiding you about what the best mechanism might be for you. You’ll find the program officer at the Institute the best fits what you’d like to do. But once your grant goes in, it’s going to switch to another side of the Institute.

Receipt and Referral

Overview

It will go to the Center for Scientific Review, and they’ll decide what study section it should go to, what is the best fit. It will go to the reviewers who sit on that study section, or who are brought in for that particular review. They will read it, give it scores, discuss it.

It then goes on to the Advisory Council and they make the final decisions regarding funding.

It’s really important to point out that we’re always told at Study Section to never use the F-word. “Funding.” It’s not our job to say what gets funded or doesn’t get funded. It’s our job to evaluate the science.

When you send your grant in, it will go to the Center for Scientific Review. They will decide where it will go after that. They have a number of responsibilities.

They have to check that you have submitted everything you are supposed to, and that you have followed the instructions. If you have not: if your font is too small, or you haven’t included what you’re supposed to, they can choose to s0end it back to you and not have it go under review. You need to follow the directions very carefully. I’ve written a number of grants, and every time I do, I download the instructions and I read them from cover to cover and I highlight the important areas. Because the instructions do change and the things that they’re looking for can vary. So I would recommend that you do that and follow the directions quite carefully.

As I said, they’ll decide where your grant will go. And that will depend on a number of things, but primarily it depends on the area of your research. For example, what if you send in a grant on speech perception in elderly people? Should that go to NIDCD? Or should that go to the Institute on Aging? There are times when you’re not sure, or when it’s not clear from your proposal. To avoid that, you should be talking with the program officer at your Institute where you would like it to go, to get guidelines on how to frame the question and frame your research in a way that will make it fit for a particular institute.

They will then assign the application to a specific Institute or Center, after that it gets an identification number that allows us to track it. Finally it gets assigned to a scientific review group, which are commonly called “study sections.”

Referral to Study Sections

Referral to a particular study section is based primarily on two things. What is the grant mechanism you are applying for? Different types of grants go to different review panels. And then it also depends on your area of research, your population, what kinds of things you are proposing to do. You can be prepared for that by going to the NIH website and looking at the various topics that are covered by the different study sections. And planning ahead to make sure that your grant goes to the study section you are interested in.

Almost all of the grants are referred to study sections that are administered within the Center for Scientific Review. There are a few that are not.

Review Outside CSR

The Center for Scientific Review covers all of NIH, but there are some grant mechanisms that are reviewed internally within NIDCD. The fellowship awards — the F31, which is the pre-doctoral fellowship, and the F32, the postdoctoral fellowship — those are typically reviewed by an ad hoc study panel or study section.

What does that mean? That means the scientific review officer will select people for that particular review based on the grants that have come in and their areas of expertise.

Typically that will be a much smaller panel than a standing study section, where they are going to be reviewing a much larger number of grants. For those of you who have been on these ad hoc panels, is that correct? That’s been my experience. Then, the K awards and the training grants, the T grants, they are reviewed by CDRC, which I believe stands for Communication Disorders Review Committee, and that is the standing committee for NIDCD. They review all of the training mechanisms.

As I said, there is a standing study section for CDRC, but many times they are going to bring in extra people or form extra panels to review these ad hoc grants. Why do they do that? It’s based on the expertise needed for the grants that are submitted.

Getting the Right Study Section

How do you get assigned to the “right” study section. The example Mario gave a little bit earlier about could you go to LCOM or could you go to auditory study section — that is something that happened when Mario and I both worked at Indiana University Medical School.

Let me tell you how you do get assigned to the right one: You should ask. You can submit a cover letter with your grant asking to be assigned to a particular study section, and explaining why it might be the most appropriate one.

You should also think about the title of your application. Many years ago, Mario and I oversaw two separate R01s at Indiana, and we called one the “speech perception grant,” which I oversaw, and we called one the “speech production grant,” which Mario oversaw, but we worked on both together. We had this wonderful idea that we were interested in perceptual processing, so we were going to change the speech perception to “spoken language processing in children with cochlear implants.” So we did. But we didn’t submit a cover letter to go with it. And it went from always having been reviewed in the auditory study section to the LCOM study section, where it was not favorably reviewed.

So we learned a very important lesson. The next time when we revised it, we changed the title back to something that was more appropriate for auditory study section. So we made two errors there. One error was that we changed the title to something that wasn’t clear. The other was that we did not submit a cover letter requesting a specific study section.

Reviewer Assignments

Audience Question

Do you get the chance to make comments about who might or might not be appropriate to review your grant?

If you feel there would be someone who may be a potential reviewer, but may not be a suitable person to review your grant, for a variety of reasons, you can specifically ask that the grant not go to that particular person. It might be things like you have a long standing disagreement in terms of the theoretical motivation for your work.

But you should be really careful about doing this. Do it judiciously. Don’t over use it. Don’t send a letter saying, “I don’t want these ten people to review my grant.” Do it very carefully and judiciously.

It is important to note that you cannot do the opposite, which is to suggest potential reviewers for your grant. And I know of someone who did that, and she was told, “Every single person that you listed here now cannot be a reviewer for your grant.” You don’t want to make that mistake.

It is a good idea to emphasize in your letter the type of expertise that is needed to review your grant. That is very helpful to the SRO.

Assigned Reviewers and Study Section Roles

Once it gets to the study section, the scientific review officer will then decide who the grants should go to to be reviewers.

The scientific review officers will choose two or three people to review the grant carefully. We will read them ahead of time, and critique them, and give them written scores for the sections that you have seen and you will see many times over the next three days: Significance, Innovation, and Approach, etc. We assign each of those sections a score.

We write a narrative in bullet points, for each of those sections: What about Significance, what about innovation.

Then we assign an overall impact score. Based on all of these individual sections, what do we give it as our one overall impact score. We submit those critiques, in writing, on the NIH website. Can I see what other people have written? No, not until the submission date has come due. Once everything is submitted, then it is opened up, and you can see the critiques and written scores of the other two reviewers who have looked at the grant carefully.

That’s what happens before we get to the study section meeting. I always look at what the critiques are from the other investigators, and I read them carefully for two reasons. First, I want to see if I’ve missed something. Because, as Elena said, you’re as equally familiar with each research area for the grants that were assigned. I want to see if I’ve missed something, and if they brought out a point that’s really good. The other reason is that I want to be an advocate for the grants that I think are strong. So if someone has made a criticism where I think they’ve missed something in the grant, or they’ve misinterpreted, then I want to go back and read the grant carefully again and be prepared at the meeting to make points that potentially rebut that criticism.

That’s how you really become a good advocate for grants in your area — or any grant that you think is good.

Now that we’ve done all that, we get to study section. What happens? For AUD study section, it’s usually about a day and a half of meetings. And what happens is we discuss a limited number of the grants. We can’t discuss them all, we don’t have time to do that. We discuss somewhere between 50% and 40% of the grants that are submitted.

What happens is the primary reviewer will be asked to summarize the grant. All three reviewers go around a give their preliminary score, and you can change that if you want to. You don’t have to say exactly what you submitted. If you think, “Oh, I read the other critiques and I don’t think it’s as good as I thought it was” or “Gee, I think it’s better” you can change your preliminary score.

Everyone gives the preliminary score. Then the three reviewers discuss it. The primary reviewer gives a brief summary of the grant, and they ask you to keep that to five minutes, approximately. So you don’t have time to convey a lot of detail about the grant. You have to hit the highlights and hit the basic idea of what the investigator proposes to do. Then you also comment on each of the various criteria. So, you comment on what is the Significance, the Innovation, etc. etc. That’s the primary reviewer.

The secondary reviewer is then asked, “Do you have anything different to add?” They don’t want you to get up and say the same thing all over again. Then the third reviewer. Typically, primary, secondary, and tertiary reviewers have differing degrees of expertise, with the primary being most familiar with the work.

The tertiary reviewer may just be asked to write a brief paragraph, and it may be that you just have expertise in one small area of the. Like for me, sometimes I’ve been asked to review grants where they are including some testing of hearing impaired individuals, and I can comment on that. Then, what happens is the discussion is open to everyone sitting around the table. They can ask questions, they can comment. Then once this discussion has come to a conclusion, the three reviewers are asked once again, what is your final impact score, what’s yours?

After that all of the reviewers around the table — many of whom have not read the grant — are then expected to assign a score. They are assigning a score based in large part on your ability to convey the strengths and the weaknesses of this application.

As I think you’ve heard many times already, it’s important to write this so that people who don’t have exactly your expertise can understand it and be your advocate.

How are assigned reviewers chosen?

The scientific review officer will choose the assigned reviewers. We talked a little bit about primary, secondary, and tertiary. First they will look and see who is already on the panel that has expertise in this area, and they will go there first. Then, if they find that they don’t have anyone who is really appropriate, they will ask ad hoc members to participate in the review process as well.

Those members may come to study section, if they are reviewing a certain number of grants. Or they may simply call in for a specific time period and review just a limited number of grants. The difficulty is that often times they are not calibrated. So, we’ve been reviewing a number of grants, we know what a three means, we know what a two means. And they haven’t heard the discussion, so that can be a little tricky.

Each reviewer gets about 10 to 12 grants. It depends on the type of grant mechanism. Last time I think I got 10, and the time before that I got 12. For a 12-page application — for a research plan of 12 pages, like an R01 — I spend about 8 hours. So I read it really carefully. I make a number of comments as I’m going through. I may be slow, but I want to be sure that I understand it and that I’m giving it the attention that it’s due. This is a huge commitment on behalf of reviewers. And we all do it because we want to move forward the science in our field and support young people.

That’s why, when you hear people talk about being cranky, it’s not because we’re inherently cranky people. It’s because we really take it seriously and we want to be advocates for you.

What do reviewers do when they read a proposal?

So what happens when they read the proposal?

We read the Specific Aims to get the overall impression. The Specific Aims are one of the most important parts of the grant. It’s the first thing you see, and it sets the tone for what is the purpose of this grant, why is it important. You should spend a tremendous amount of time thinking about your Specific Aims.

Obviously, we read the grant and make notes. And one of the things I like as a reviewer, is when I come to the Significance paragraph wherever it is, and I see a sentence that says, “This work is significant because…” Then I say, “Oh, here it is” and I can look for that. I want to know why it is theoretically significant, and why is it clinically important or significant. And it may not be both, but if it is, make sure you tell me that.

Then we look at the strengths and weaknesses for each of the review criteria. The NIH gives you a template to do this review. It lists the criteria, then it says “strengths” and you list them as bullet points. But not just a phrase, a sentence or two or three about each of those. Then the same thing, a weakness. So you’re supposed to look at each of them.

And when you come to the point where you have to make a score for that you’re going to weigh: how many strengths are there as opposed to how many weaknesses, and how important do you weigh each of these. It’s important to do that carefully. So you come up with a score.

Then, as I said, you submit your written critique and your score — it asks you to submit a written critique for each of the sections, then an overall impact score. Then you attach your written critique. And you do all this on the website.

Study Section

Study Section is about 10 to 20 people who have expertise inside and outside your area of interest. On the Auditory Study Section there are maybe two or three who have clinical interests or interests in hearing science in kind of an applied way. Then there are a number of people who are engineers or molecular biologists. There are people from all kinds of basic science backgrounds and clinical or applied backgrounds.

Many times they’ll be talking about something that you don’t know anything about. Like “knockout mice” I don’t know very much about knockout mice. But I hear that word a lot. So you have to be prepared to listen to the presentations and weigh what they say.

You can find the study section membership rosters online on the NIH website, and you should probably look at that. It doesn’t mean that when your grant goes to that particular study section it will be exactly the same, because there are ad hoc members who are added as needed. Also the typical term is three times a year for four years — or now they’ve changed it to two times a year for six years. So someone may have rotated off, or someone may not be going to that particular meeting. But it gets you some general idea.

Who runs the meeting?

The meeting is run by the scientific review officer — the person who assigned you the grants.

Then there is also a study section chair. That person is someone who has been on that study section for two or three years. They take that role for an entire year, and it’s a huge responsibility. They guide the discussion, they listen to all of the critiques. After the final scores have been submitted again, they summarize the discussion, even if it’s in an area they know very little about. So they have to be really on top of their game, paying attention and listening.

The scientific review officer is there to keep things flowing. To make sure that you’re following all of the guidelines. She looks for conflicts of interest before you get there and will notify you who you are in conflict with. He or she is a very important member also.

The scientific review officer might step in or the chair might step in and say, “It seems to me that we’re reiterating the same points, so let’s move on to keep things going.” Or the chair might say, “Gee, I’ve heard an awful lot of criticisms about this grant, why is it getting a 2?” So they try to keep you calibrated and keep you going.

Which grants will be discussed?

Which grants are discussed? It’s based on their preliminary scores. So when you submit your overall impact score, those are ranked. They draw a line at the mid point and — now think it’s more like 40% are discussed and 60% are not.

The idea, then, is to give the panel time to really focus on the grants that are likely to have to highest impact and be most significant. Before the meeting, you can ask, if a grant that you reviewed or anyone reviewed gets a score that puts them under that 50% point, you can ask to have that grant discussed, and it will be.

Why would you ask that? What would motivate you? I’ve asked for that before for a grant that — I think it got a 2, a 3, and an 8. Remember 1 is good and 9 is bad. And so I thought that when there is such a discrepancy in scores, let’s discuss it. The likelihood that it will make it through is small, but you’d at least like them to have to opportunity to get the discussion and feedback.

Conflicts

How are conflicts handled? If you are at the same institution as the PI who submitted the grant, you may not participate, and you must leave the room, and you don’t score it. If you have worked very closely in the recent past then you will be in conflict and you leave the room.

When you are in conflict, you don’t listen to the discussion, and you don’t score it.

The Scores

We talked a little bit about the “new” scoring system. There are criterion scores and an overall impact score.

Scoring System

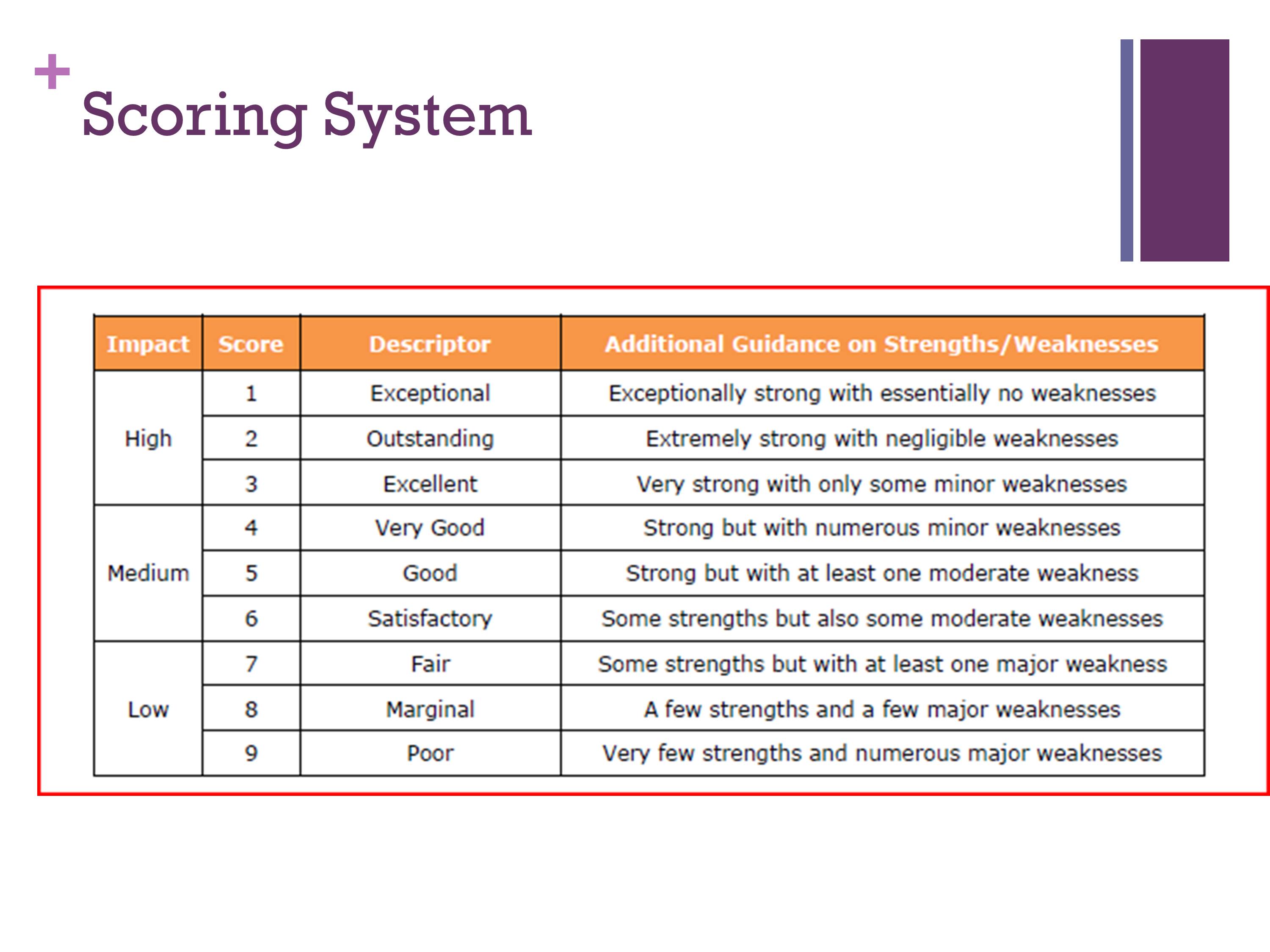

This is a little hard to see, but every reviewer is given this as a guideline. We are supposed to follow this. A 1 is the best you can get. And a 9 is the worst you can get. And you can see that 1, 2, and 3 correspond to high impact; 4 through 6 medium impact; 7 through 9, low. It gives you a descriptor, and then it gives you some guidelines. So if there is something that is very strong with a few minor weaknesses, then that would get a 3.

So you’re supposed to keep this in mind as you’re scoring. As a new reviewer, you’re always really nervous, when it’s time to see the other people’s scores, and the other people’s discussion of the grant. As you become more seasoned, you find that for the most part people are pretty close.

What they don’t want to see is that everything is clustered in 1, 2, 3, and 4. Because then you can’t separate out a very good grant from a good grant. They encourage you, that if you see one that is not very good, to give it a 9 or 8 so we can spread the range out. That’s when we talk about calibration.

Criterion Scores

The scores are given separately for each category.

Categories: Significance, Investigators

These are some guidelines that we’re given as reviewers. When we’re looking at Significance: will this make a difference, will it move the field ahead, and what is the importance of this problem.

The Significance really is very important — I think Significance and Approach are probably the two most heavily weighted aspects of a grant. But then the rest have to be good, too.

Then they look at Investigators: whether you’re productive, whether you’ve had research funding. If you have a good track record. If a researcher is going to be your mentor on a training mechanism, then they would like to see, have they had previous trainees, where did they go, were they successful. You have to think about that. They want to make sure you have the skills and techniques.

I remember reviewing a grant where it was an outstanding grant, but it was proposing to test children and adults and no one on the team had ever had any pediatric experience. So the next time they revised it, they added a person with pediatric experience and it ended up getting funded. So, we’re going to be looking for things like that.

Categories: Innovation

Innovation, again, things don’t have to be innovative to be a good grant — though they would like to see innovation. And innovation can take a variety of forms. You might be developing a new tool or a new paradigm. You might be using an existing tool or paradigm in a new population. There might be a variety of forms.

Categories: Approach, Environment

Approach is probably one of the most important sections. When I’m reviewing — and I think most reviewers are like this — you have to consider all of these things: the methods, the rationale. The guidelines now say that reviewers should not focus on the details of the study, but on the conceptual issues. But you have to put enough details in there for us to know that you understand the work and that you can do it.

One big no-no that I’ve really seen lately is that people try to put the details of their approach into the Human Subjects section: here are my participants, and here’s what I’m going to do. We are really instructed to ignore that. Our job when we read the human subjects section is do we have concerns about safety and protection of the subject. It’s not to be saying, “Oh, now we know they’re going to do that.”

It’s a challenge. You might have 6 pages, you might have 12 pages. But you have to think about a way to always include a power analysis, they want to see that. And you should include a description, however brief, of your statistical analysis. Because they are looking for that.

Then, the Environment is: can you do the work where you are? Do you have the subjects you need? Do you have the equipment and the infrastructure? You can certainly put in the equipment you need to do the work, but you don’t want them to think that you’re padding the grant so you can build a lab from that. You have to be careful about that.

I do cochlear implant research with children. I always include in my Approach the number of potential subjects who have been implanted and meet our criteria and are available for recruitment. So, I show them that I’ve done my homework. You’ll get grants from people who say they want to do X, Y, and Z, but they are nowhere near subjects. So think about that, and make sure you include that.