The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

If we want more evidence-based practice, we need more practice-based evidence. Well, there’s the title and there’s the answer.

Let’s define these two terms.

Fidelity. I suggest that the way it’s most commonly used is adherence in the implementation of an intervention to exactly what the RCT or next-best evidence demonstrated to by efficacious under controlled experimental conditions. Note that — and you can debate any one of the words in this — but I think most of the evidence we’re trying to apply in evidence of our implementation is efficacy evidence. Because of our demand for randomized controlled trials. And those under pretty hot-house conditions usually that don’t really represent the realities under which we would implement them.

Adaptation is the cautious but purposeful revision of the experimentally tested intervention to make it fit better with the patients or circumstances or both, in which it would be or is being applied.

Now I think the term adaptation has been tainted with the recognition that it is not cautious and purposeful in the revisions that people are making in the evidence base. It is often haphazard, it is often fly by the seat of the pants.

What I am offering is an appeal that we make it more systematic. That we approach adaptation not as an event, but as a process. It’s not an event of haphazard application, it’s a process of testing the necessary modifications that we need to make in evidence based practices for them to fit and be appropriate for the patients, the populations, the settings, the circumstances in which we would apply it.

Three Paradoxes

We are faced with three paradoxes in all of this. The internal validity/external validity paradox. The more rigorously controlled a study testing the efficacy of an intervention, the less reality-based it may become. So it cannot be taken to scale or generalized without recognizing those very particular circumstances under which the evidence was generated.

The specificity/generalizability paradox. The more relevant and particular to a local context — the one in which we’re trying to implement it — the less generalizable the results of that implementation will be to other settings. So let us be modest about our claims about what works for us in our setting. Not necessarily being generalizable to other contexts.

So the internal/external validity debate has been going on for decades. Donald Campbell and Julian Stanley developed their matrix of threats to internal validity and threats to external validity, they were essentially saying that we can generalize about the external validity of an intervention if we’ve paid attention to the threats to external validity.

But then Cochrane came along and defined external validity in such a way that was widely appreciated and accepted. But he’s saying, in effect, if you reflect on his approach to external validity, that there can be no real external validity. We’re going to have to test the applicability every time we take it to another setting or another population.

All of what I’ve said so far applies primarily to the question of “How different is your setting, your population, your patients?” For many practitioners and policy makers the most useful data from a trial would be subgroup analyses of which patients or subjects in an efficacy trial benefited from it, and which ones didn’t. What you get in the literature are mean differences, and that tells you little or nothing about for whom it was effective, under which circumstances, and so forth.

We don’t get much subgroup analyses reported in the literature because statisticians, about 30 years ago when there was some major NIH trial called MRFIT, a multiple risk factor intervention trial on cardiovascular risk factors, with a very large investment, failed to achieve much more than lackluster results.

So there was a scramble, after spending that much money on a trial, to understand with whom it was effective and who didn’t benefit. But the statisticians hit the ceiling and said you can’t do that because the subgroups weren’t randomized.

So now editors have adopted the posture of not accepting subgroup analyses. So you’re not getting them.

The literature delivers to you a statement about relative effectiveness, relative to a control group, for the average effect size relative to the average effect size in the control. So we don’t even get the subgroup analyses that might make adaptation more scientific in our setting.

What I’m arguing and campaigning on, if I may, in the spirit of full disclosure. Is that we really ought to be approaching adaptation as a process. A process by which we can make the changes — the lack of fidelity, with all of its moral overtones. If we can make that more scientific. Not make a special intervention less scientific by applying it in settings in which it wasn’t tested in the first place.

That’s a rather contorted argument, I know, but I hope you’ll at least give it consideration.

So what do we have to cover, if we’re going to grapple with these paradoxes?

Fidelity and Adaptation

Why is fidelity an issue?

For one, practitioners have demonstrated, I think quite sensibly, their resistance to evidence-based guidelines when it’s clear to them that the studies on which the evidence-based guidelines are promoted were in very specialized populations.

They perceive that it’s an unrealistic burden on their practice, often, because not a lot of consideration is given to practicality and cost.

They perceive that it’s based on research that is too far removed from their realities, which is usually if not certainly right.

Secondly, researchers have this belief, out of hubris or conflict of interest, in the certainty or universality of their findings. And they prepare their manuscripts with as much subtlety as they can bring to bear to convince the editor it has those features.

There’s experience in some sectors that what’s passing as evidence-based practice is not what the evidence showed. Very often the evidence has been — I want to be very careful here — Sometimes the evidence has been fudged a little in order to make it publishable.

What needs to be considered in arriving at conclusions concerning fidelity versus adaption?

For one, as I understand your work, you need to ask yourself to what degree is the intervention a strictly clinical, physiological, anatomical intervention on the human physical or physiological organism. And to what extent is there a behavioral component included? As soon as you introduce the behavioral component, you really start making it messy from a randomized controlled trial perspective. You’re introducing infinitely more variables. Infinitely more.

Even more so, if the intervention is not on an individual patient, but on a community. If you take your intervention out to screen people for example, you’re trying to recruit people from very diverse populations. In different communities. Each with their different cultural, historical, economic circumstances. And that lends even more variability.

For all of those reasons, and these further reasons, fidelity has become an issue.

Researchers test an intervention for its efficacy. They do a rigorous test that qualifies it for the official — usually a federally promoted and developed list of evidence-based practices — based on systematic review, several different trials, that produce guidelines.

Most of those lists have given, in my opinion, too little consideration to external validity because they are so obsessed with pinning down the internal validity, which drives most of the decisions about what qualifies to go onto the list.

Practitioners try to incorporate it into their programs and other populations in circumstances than those in which the studies were done. A poor fit produces failure of programs. Practitioners are blamed, then, for not implementing with “fidelity.” Well, now the, in many cases, the investigators come back and say, we can fix that. We’ll sell you a training program. So you get this cycle of conflict of interest in some areas in which interventions have been developed for sale.

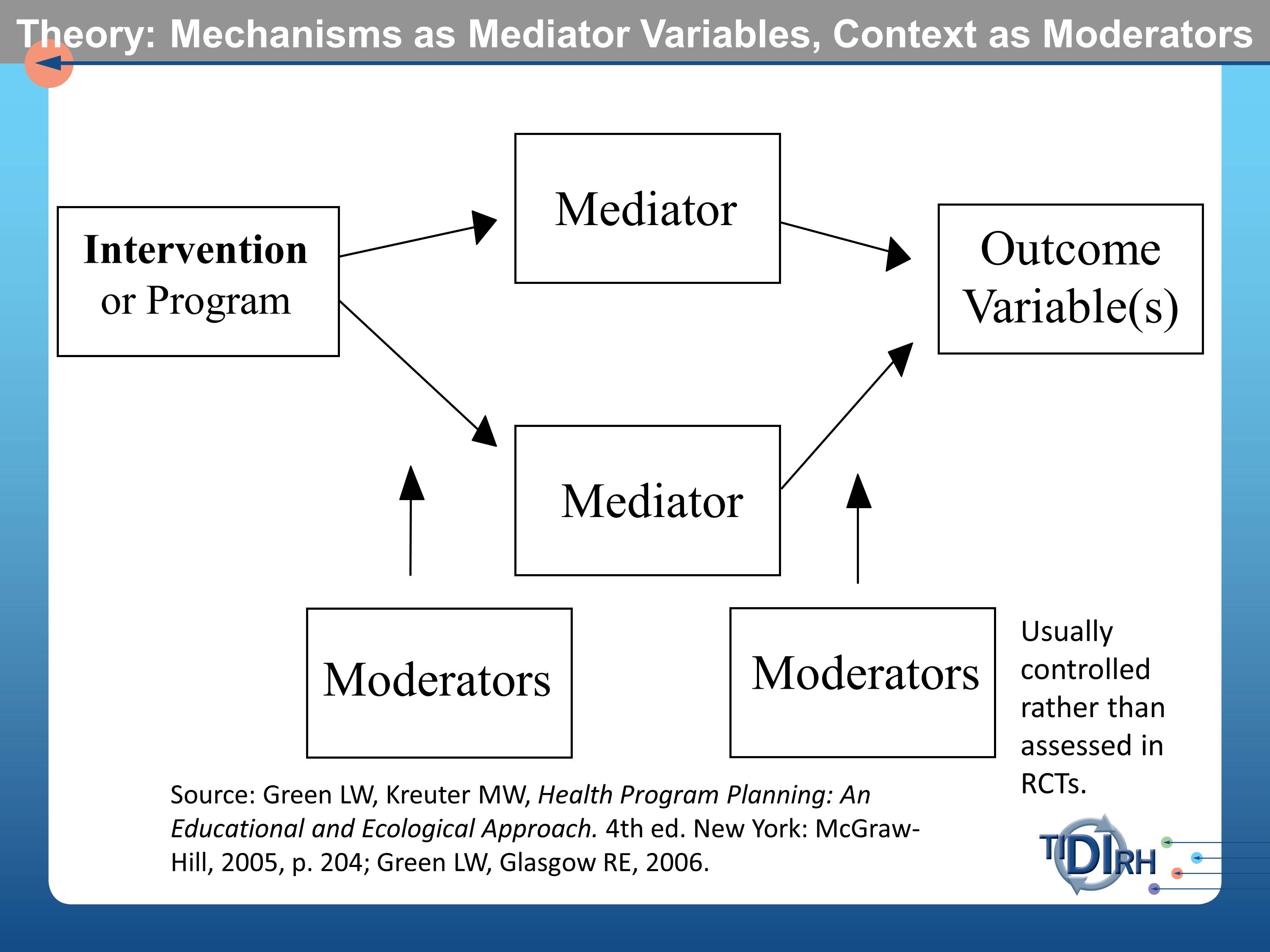

Much of what has been said earlier this morning by Drs. Aarons and Proctor, point us to the importance of having a model, a theoretical model that examines the mechanisms by which we assume the intervention to effect and outcome. These are often referred to as mediator variables in the modeling literature. They get tortured usually in these randomized controlled trials to measure them as assiduously as possible.

But what doesn’t usually get measured — and often not even reported — are the moderator variables. The contextual circumstances in which the intervention was conducted. And the contextual circumstances in which the mediators might or might not influence the outcomes. Those moderator variables are usually controlled rather than being assessed in randomized controlled trials.

I made the case that we often don’t see any subgroup analysis. We also don’t usually see much about the context.

Here’s a chart from the book that Enola and her colleagues have recently published and I know you’ve seen and heard of material from it in these discussions.

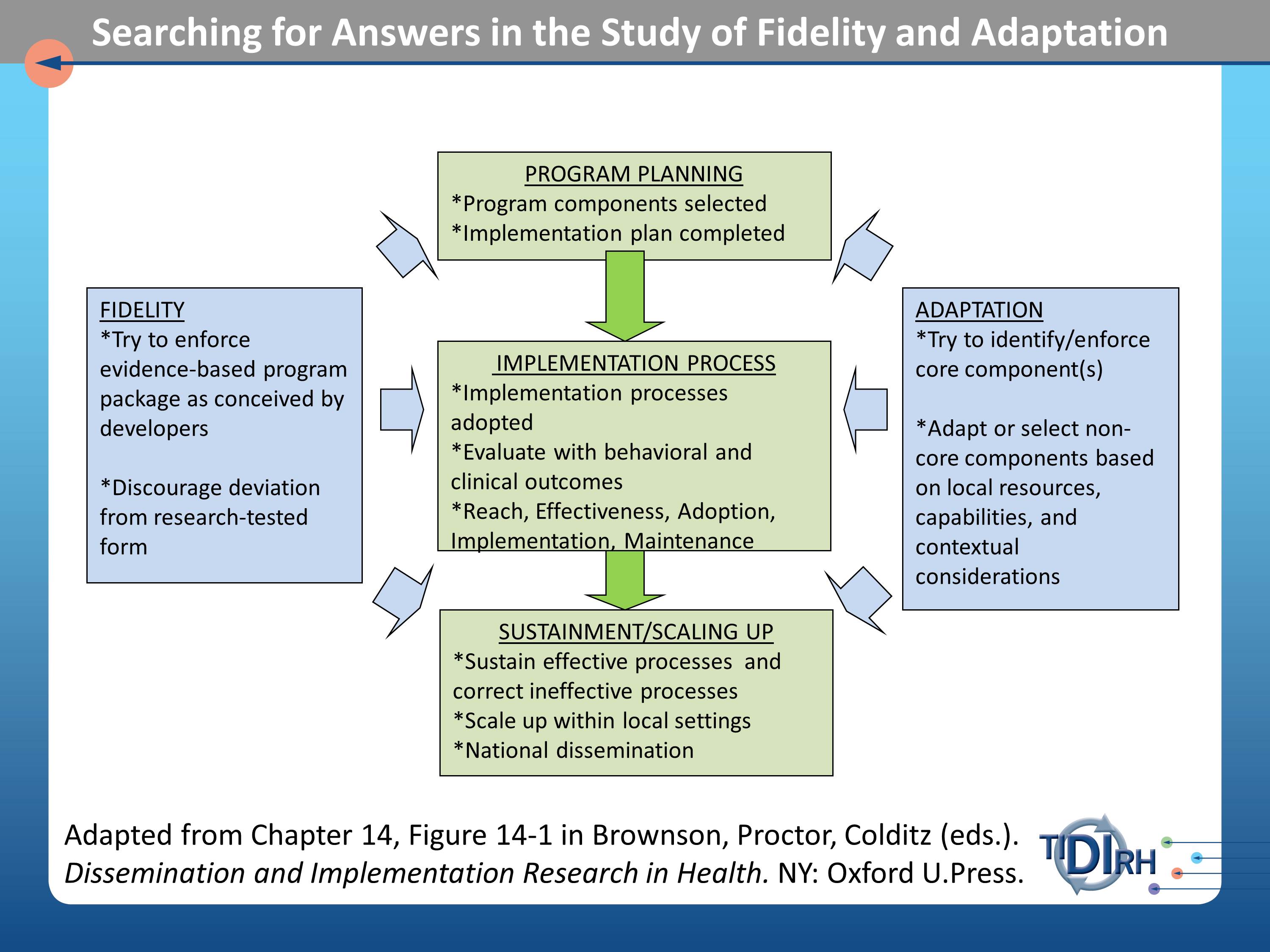

What we are trying to grapple with here, then, are issues of fidelity as they may affect the program planning process, that is the organizational decisions about what will be asked of practitioners to implement, the implementation process itself, and the sustainment or scaling up process.

These three parts of process that we want to test for the fidelity and outcomes of interventions. Adaptation addresses the same three parts of the process with the question — the comparative effectiveness question — if we need to adapt this intervention, because our population differs in the following ways from those in which the trials were done. If we need to adapt it, how can we assess the relative effect of those adaptations? It becomes a comparative effectiveness trial.

Example of Adaptation as a Process

Here’s an example, because I know it’s all been pretty abstract up to this point.

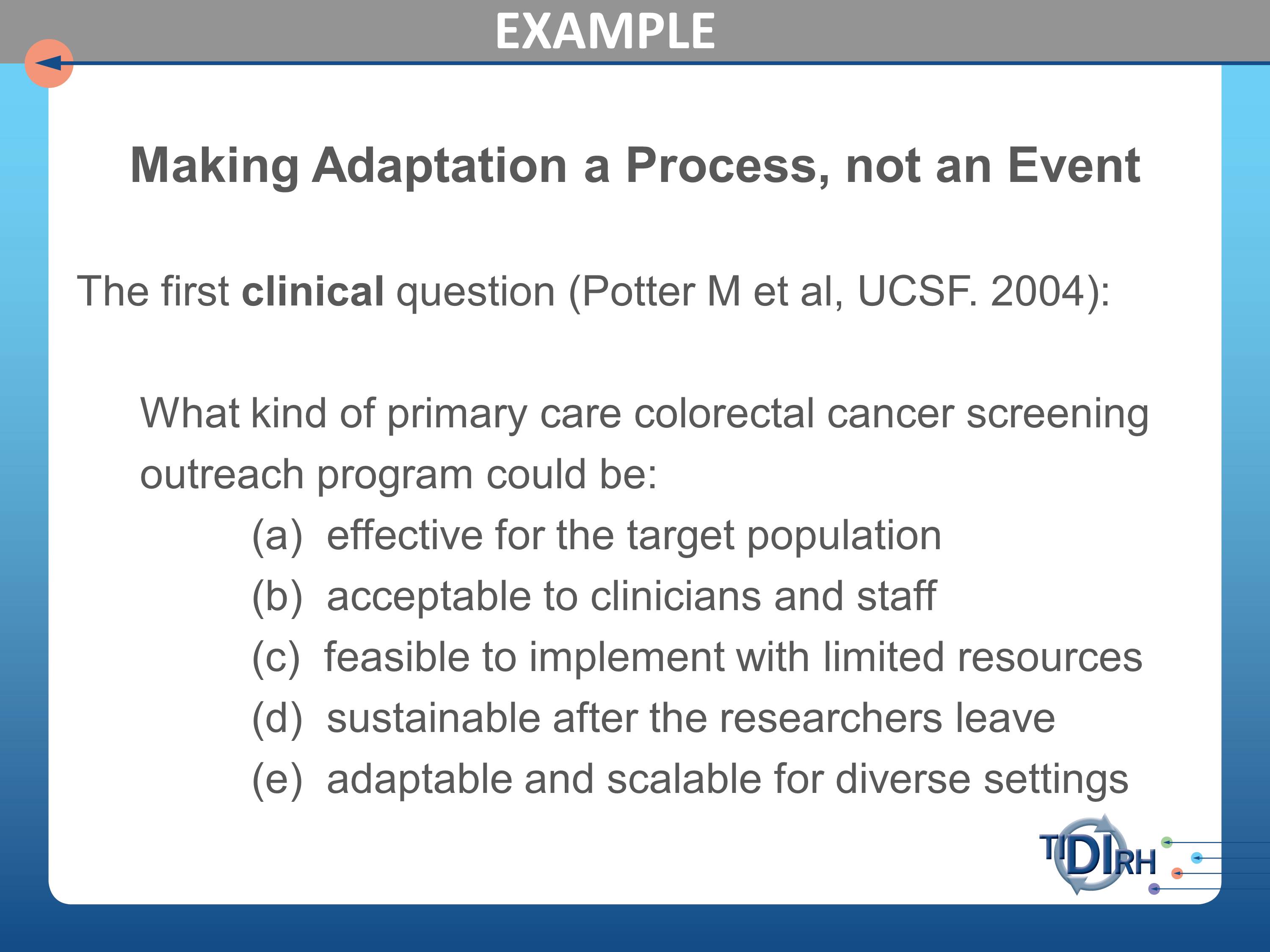

Here’s a series of studies that were carried out at University of California at San Francisco, led by Michael Potter who is a professor in the department of family and community medicine, in which he posed initially the clinical question, “Which kind of primary care colorectal cancer screening outreach could be effective for the target population, acceptable to clinicians and staff, feasible to implement with limited resources, sustainable after the researchers leave, and adaptable and scalable for diverse settings.”

I dare say that these are questions you could well ask of a variety of your interventions when you’re trying to take them to scale.

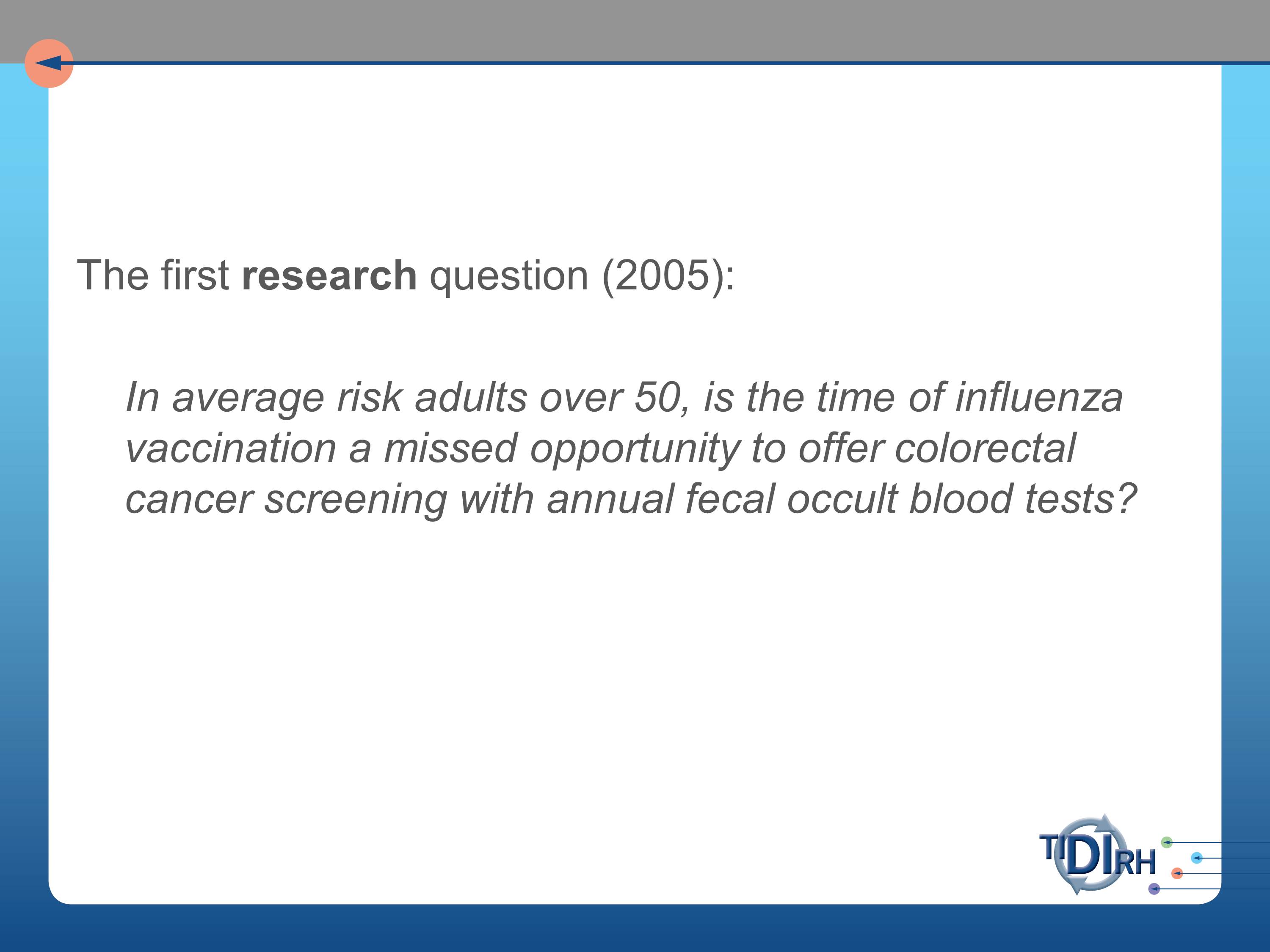

The research question, following on those practical clinical questions, was whether in average risk adults over 50, is the time of influenza vaccination a missed opportunity to offer colorectal cancer screening. Wait a minute. Influenza? Where did this come from? We’re talking about colorectal cancer screening.

But, we’re very concerned in colorectal cancer screening and in cancer mortality data with the tremendous disparity between the people who are getting such screening and those who are not. And between those who are benefiting from such screening and those who are not.

And it’s partly because the poor populations have not been convinced this is a priority for them. But boy do they line up for immunization for flu vaccine. When the flu season is announced, they are out there lining up at these clinics to get their flu shots.

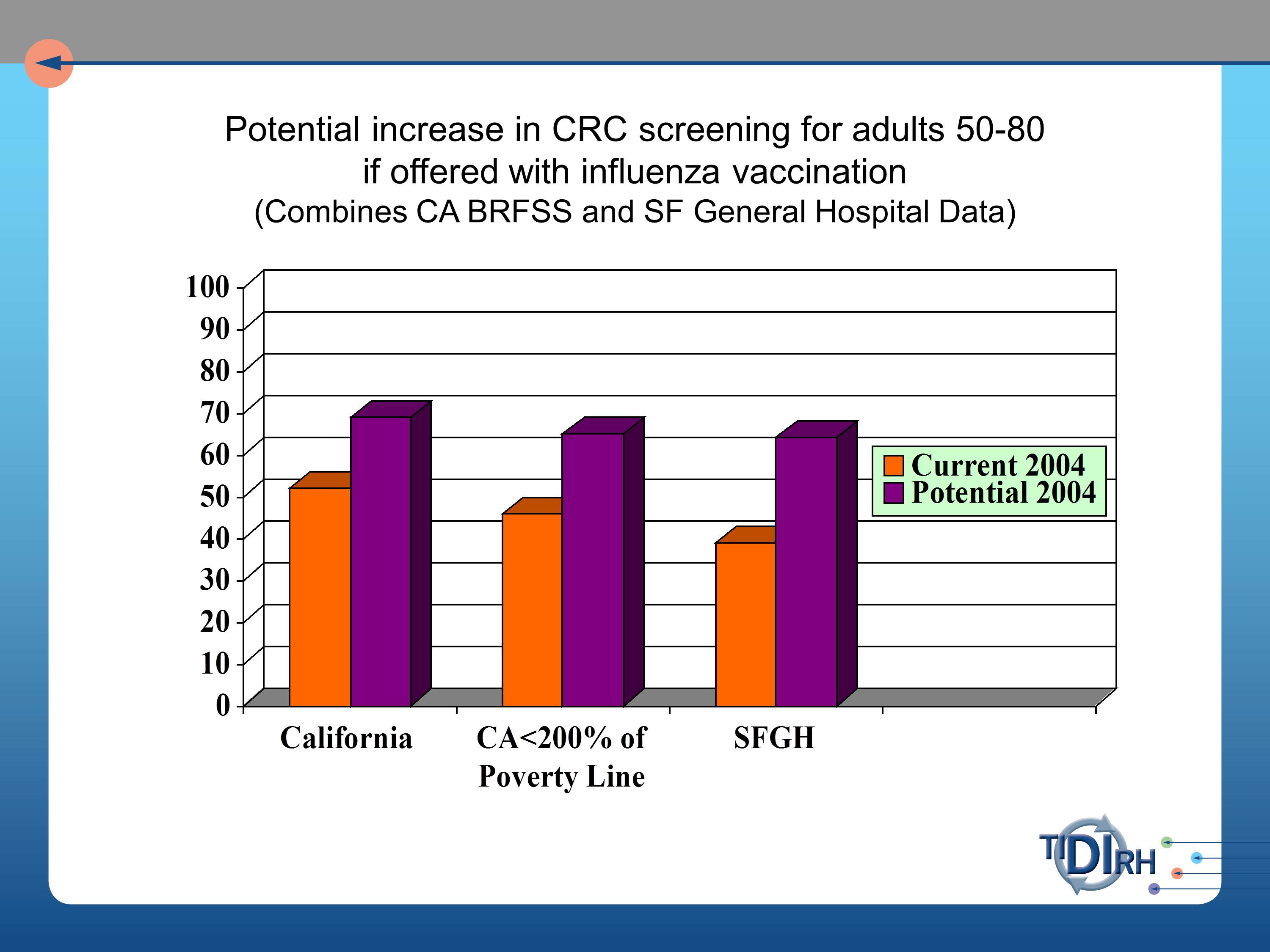

So, our question was, will the offer of a fecal occult blood test at the time of getting the flu vaccination produce a more equitable distribution of colorectal screening opportunities. And if we did so, what would be the gain in numbers of people reached?

And reach is a very important part of understanding a total population impact in public health benefit.

A second research question was, can we show that a FLU-FOBT (fecal occult blood test) program can work?

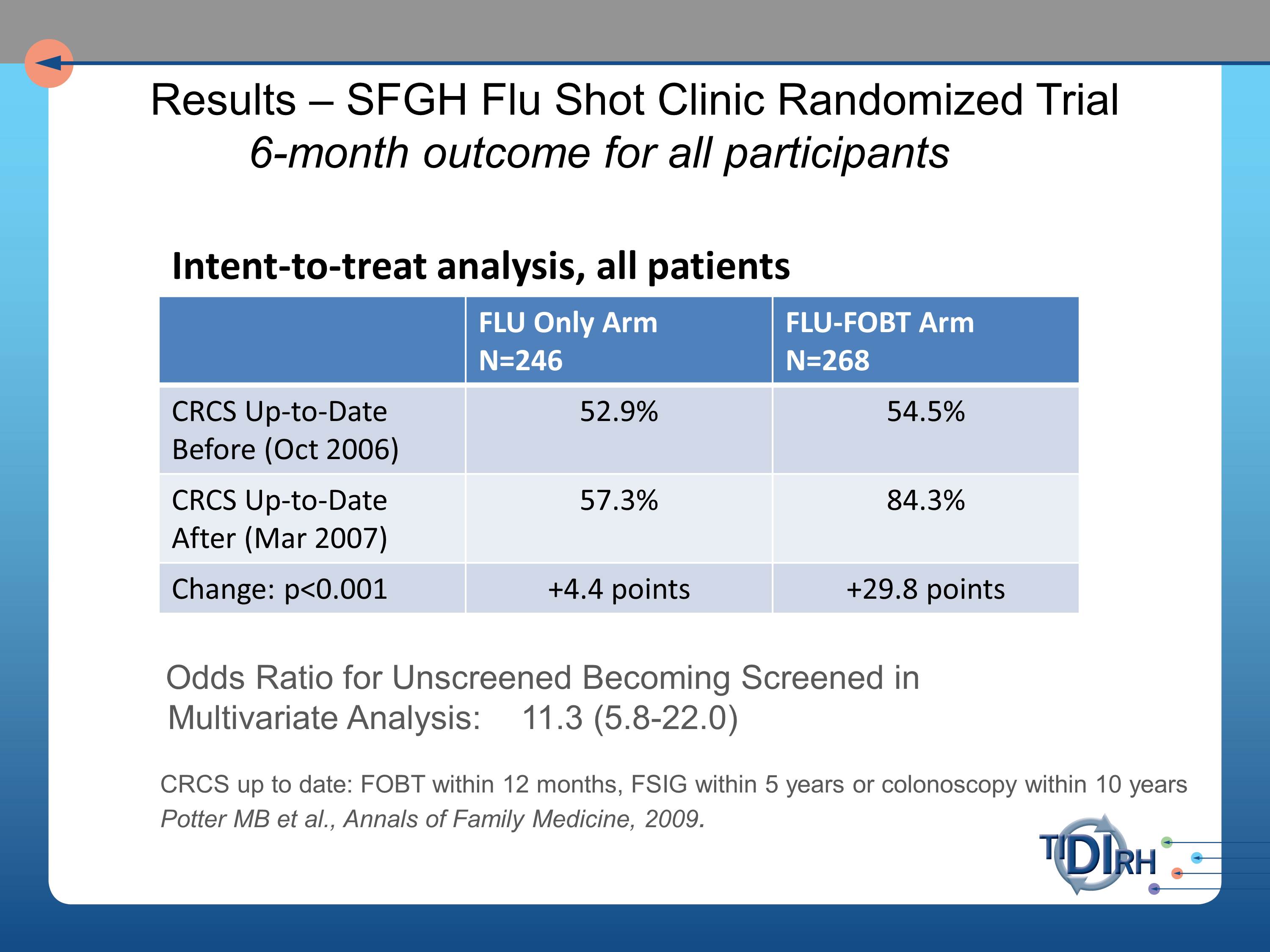

So we set about approaching this at the San Francisco General Hospital’s Family Health Center. And in the intent to treat analysis of all the patients that were coming through that flu shot clinic, we saw very substantial improvement in the FLU- FOBT arm of those who were up to date in their colorectal screening six months later.

What I’m unfolding for you here, I hope, is a process by which you ask your questions in a logical, sequential way as you proceed from taking an evidence-based practice to scale. Or taking it to communities in which the original tests were not necessarily conducted. Or trying to get more people to buy into it.

So the next research questions were those in pursuit of external validity. Can it work with less hand-holding of the clinical staff? Because that initial intervention that was so slam-bang effective involved a lot of hovering of researchers over the shoulders of practitioners.

Second, can it be integrated with primary care? Third, can it work in managed care? Fourth, can it work in pharmacies? These are all settings in which we’d like to know whether this same intervention has actionability.

And can it be sustained where it is introduced?

We set about to have intervention implementation studies in each of these settings. We worked with the San Francisco Department of Health. And note that we had to get a different grant from a different source for each of these because NIH only had so much patience for this sort of work, and understandably so. It might have looked very redundant to them. We had a grant from the CDC for the public health application, from Kaiser Permanente for the HMO implementation and a separate grant from the American Cancer Society Research Scholars program. And for the Walgreens Pharmacy trial, a grant from the Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust.

I’m not going to try to describe each of these to you, but if you’re interested in the results, here’s the one-word answers:

- Can it be implemented with less handholding? Yes.

- Can it be integrated with primary care in resource-limited community health centers? Yes.

- Can it work in managed care? Yes.

Each of those yes’s is qualified by the adaptations that were made to make it work in those other settings. And a lot of those adaptations involved the participatory approach to understanding what adaptations were needed. Which you heard a lot about yesterday in the presentation on participatory research, and I do commend that to you as a very critical part of the adaptation process.

- Can it work in pharmacies? Probably.I think our conclusion had to be hedged very much by the particular nature of the pharmacies in which we tested it.

- Can it be sustained where it is introduced? Often. And so far.We’re not so certain it will be sustained beyond the time that it’s had to play out.

Final Perspectives on Aligning Evidence with Practice

And I’ll leave you with these thoughts. Here’s an approach to aligning evidence with practice that I’ve tried to encompass in my approach to adaptation. And it involves matching, mapping, pooling, and patching.

Matching refers to understanding that any intervention is going to involve, especially if it is an effective one, multiple ecological levels of a system: organizational levels, down to practitioner, down to patients. So you want to match whatever evidence you can that comes from those different settings. Often the clinical trials that have led to evidence based practices on the list of recommended practices, the best practices, are from one level or another, but seldom ecological studies. So you have to draw evidence from several levels.

Mapping refers to using theory to understand a causal change. We talked already much about the notion of modeling.

Pooling refers to drawing the experience from various practitioners who have dealt with the problem at one level or one context or another to blend interventions from their experience to fill gaps in the evidence for the effectiveness of programs in similar or different situations.

Patching refers to pooling the interventions with the indigenous wisdom and professional judgement about plausible causes and interventions in particular settings to fill the gaps in programs for a specific population.

The take home messages I leave you with are, first, be suspicious of demands for fidelity when the intervention is on behavior, complex organizations, or on whole communities.

Secondly, draw evidence from the practitioners, patients, organizations or communities in which the intervention would be adopted or adapted. The practice-based evidence will be needed to complement the evidence-based practice.

Try to identify the core elements or functions of the interventions that must be implemented with fidelity as distinct from the adaptable elements, the forms of the intervention, that could be matched and varied with the context and persons. One of my favorite articles on the subject is one by Penny Hawe and her colleagues called “How Out of Control Can a Randomized Controlled Trial Be?” It was published in the British Medical Journal. What they were really trying to do is say, here’s what the clinical trial showed us under highly controlled circumstances. Now, as we take it to the community or to scale, we need to consider breaking out of that control to a degree, necessary to allow variation in the form, but not the essential principles or core elements underlying the intervention. That’s where the theoretical modeling comes particularly into play.

Finally, measure forms (duration, strength, intensity, content) of the implementation, so you can evaluate it. And it is evaluation in real time, with real people, real practitioners, and real patients in real environments that will ultimately answer our question about fidelity versus adaptation. And more broadly, about implementation.

Questions and Discussion

Audience Questions

Question: I was really intrigued by the idea that you had compliance with the vaccine protocol, and then you added on the colorectal screening. One could imagine that there would be a lot of different things you might want to do, but if you did too much you overwhelm the system. How do you decide what your priorities are in terms of what you’re going to add on to something that’s working?

I think the first criterion would be simplicity of integrating it under the circumstances of the practice for which they came to be served. So, the FOBT test is a take-home test that allows people to do their own stool sample and then mail it (it comes with a mailer) so they can mail it to the laboratory and get their result in a reasonable amount of time. And an opportunity to schedule the appointment for colorectal screening.

So simplicity was its major virtue that allowed us to integrate. Most of the other possibilities that you mentioned — and I’m sure have been considered for insinuating into flu vaccination lines, would be much more complex. That would be the number one criterion.

Question: As the folks here build research programs, is it appropriate for them to be implementing these programs, knowing that they have an interest in promoting the findings? Or should, instead, we be handing this research to others to implement it?

And as soon as I take that stance, I become an enemy of the randomized controlled trial, and that’s not my intent. I’m arguing that the trials give us the evidence, but we need an independent process for examining implementation.

By independent, it doesn’t mean the scientists have to be run off the scene altogether. It means there need to be some controls built in so that they’re not simply ramming it down the throats of the practitioners. I loved Enola’s charming slide that has the guy sending out the memo, “This will be implemented Monday morning at 8 am.” I think we’ve got to engage the practitioners in a participatory process of helping us decide, how we can make this work in our setting.

Question: You mentioned community-based engagement as a source for adaptability. Can you talk a little bit more about how you utilize this information?

We have to look at the range of stakeholders for the issues we are addressing. In speech and hearing, the range of stakeholders is probably much broader than the usual clients. We can engage those stakeholders in helping us set the research agenda and priorities, and in deciding what is the researchable object — the intervention — and how does it need to be adapted. So those stakeholders can collaborate in assuring its sustainability. Those are the kinds of issues community brings into the formula.

Audience Comment: The word “adaptation” strikes terror into the heart of the PI who has attempted to document efficacy and evidence in an area where there has never been evidence before. On the other hand, we want to scale up our interventions so they are implemented. We can’t run a study on every variation of a treatment, but we want to be implemented in environments.

David Chambers, NIMH:

The goal is not to provide terror. In the past we were looking at our intervention as a package, and everyone was going to get the package, and then we were going to see what was the outcome of having received that package.

Especially in the mental health space, there has been more thinking about what is the differential impact of individual components of that intervention. But adding that information — if one thinks these are the core components, then what is the evidence behind that, and how does that give us more to go on, will help as we’re thinking about bringing the intervention further. It used to be, we would look at only whether this package is better than that — it was just assumed, you have to do the package.

That’s one key area where we can do a lot better. It’s not that we have to throw out the evidence that’s been generated. But what’s the additional context we can provide? There are some reporting efforts in terms of CONSORT and others to say the more we’re able to report in terms of the design, that’s going to give us more understanding to carry it further.

Lawrence Green:

I think part of the comment was for the trialist who struggles with the issue of fidelity in the trial. I don’t think anything we’re arguing is against that.

Clearly you can’t have practitioners going off in all different directions when you’re specifically doing an efficacy trial. We’re talking about what happens after you have that initial evidence and you’re taking it to scale, and you’re taking it to other settings and populations.

Your second point is that you can’t do RCTs in all the settings, with all the variations. I don’t think we’re arguing that, either. I think evaluation of programs as you adapt them is the ongoing mechanism for studying ways in which adaptations work in different settings.

In terms of maintaining the core elements, and distilling them out across settings — there’s a common factors approach and a common elements approach, in both cases trying to identify in a systematic way what should really be held.

One of the challenges that we on the scientific end have not done as much as we would ideally have liked to, to be able to inform that next step. So over time we’re able to understand more about the how and why things work. It’s also where NIMH has been trying to revamp its RCTs, so that for every trial that doesn’t show a benefit, there is much more understanding of why that didn’t happen.

Larry talked about moderators and mediators, and that’s one step. It’s easier for some on the experimental therapeutic side to say there’s a receptor in the brain that we’re trying to hit. If we don’t hit that we’re unsuccessful. But the broader thought about understanding what you’re targeting, and is that target underneath the overall outcome being engaged and can we improve from it. Focusing on the core elements is a step ahead of where some of the folks have been, where they’ve just said, “We like our package.”

Audience Comment: You can only allow a strict emphasis on adherence to RCT methods and the manual used in RCTs if you define evidence-based practice as only looking at external evidence. If you’re going to use the other two parts of EBP (concern for the professionals’ interests and expertise and the clients’ interests and expertise) it seems we are bound to look for ways to adapt the interventions. We can’t not do that, or we are not doing our job.

The presentations today have signaled the sentiment of a number of people engaged in that enterprise that we can’t continue to play by NIH rules alone, as they have grown up through the peer review system. What we need to turn to, and what we find ourselves turning to are other agencies that have a stake in the implementation, like CDC, HRSA, CMS with its PCORI grants, EPA, the Department of Agriculture. All of them are delivery agencies who have a much greater stake than NIH in what happens when they turn the evidence loose out there. That’s where we have the opportunity to evaluate programs as they are implemented with a much greater sense of support from the agencies who have a stake. That’s my sense of the bureaucratic world view of this.

David Chambers:

And it’s not necessarily the case that an adaptation must be necessary to think about some of these other domains.

But if nobody is going to come to the place where the service is being delivered, it doesn’t matter what it looks like, it’s just not going to be received. If you can’t work on access, if you can’t work on a better organization of services — it’s not only that one says, we have this intervention and there’s no hope of it fitting anywhere without us thinking about adaptation.

What I saw was there were more cases of someone saying, “If that treatment isn’t being received, it’s probably the problem of that person who is not showing up to get it” rather than trying to think if there are certain targets that may require adaptation or rethinking.

It is important not to discount the good evidence that has come from interventions. We just need to understand the nuance and that we do, at times, need to be thinking about adaptation. Or at least to be asking the question: “Is this able to be delivered as it is designed?” Rather than just saying, “It will be, and if that doesn’t happen, it’s someone else’s problem.” Which is not the way people in this room think about it — but it is how others have thought about evidence.

References

Cohen, D. J., Crabtree, B. F., Etz, R. S., Balasubramanian, B. A., Donahue, K. E., Leviton, L. C., Clark, E. C., Isaacson, N. F., Stange, K. C. & Green, L. W. (2008). Fidelity versus flexibility: Translating evidence-based research into practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), S381–S389 [Article][PubMed]

Green, L.W. & Kreuter, M.W. (2006). Health Program Planning: An RCTs. Educational and Ecological Approach 4th ed. New York: McGraw- Hill.

Institute of Medicine. (2010). Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention: A Framework to Inform Decision Making. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ottoson, J. M. & Hawe, P. (2010). Knowledge Utilization, Diffusion, Implementation, Transfer, and Translation: Implications for Evaluation. Jossey-Bass.

Further Reading on FLU-FOBT

Potter, M. B., Somkin, C. P., Ackerson, L. M., Gomez, V., Dao, T., Horberg, M. A. & Walsh, J. M. (2010). The FLU-FIT program: An effective colorectal cancer screening program for high volume flu shot clinics.. The American Journal of Managed Care, 17(8), 577–583

Potter, M. B., Tina, M. Y., Gildengorin, G., Albert, Y. Y., Chan, K., Mcphee, S. J., Green, L. W. & Walsh, J. M. (2011). Adaptation of the FLU-FOBT program for a primary care clinic serving a low-income Chinese American community: New evidence of effectiveness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved,22(1), 284–295 [PubMed]