About Peer Review

What is peer review?

The peer review process…involves the assessment of an article by volunteer reviewers (blind to the author and working independently of one another) who engage in the problem-solving task of identifying flaws within the research itself or its reporting and determining the overall value of the work (Kassirer & Campion, 1994). In doing so, the reviewer’s task is fourfold: (1) to critically examine the science itself, (2) to carefully study the reporting of the work, (3) to determine the overall importance and possible impacts of the work, and (4) to judge whether the work warrants publication in the journal for which it is being considered—that is, whether it surpasses the “rejection threshold”. (Kassirer & Campion, 1994)

~ From Justice, L. (2008). The Peer in Peer Review. Am J Speech Lang Pathol, 17(2), 106.

Why is peer review such an important part of scholarly publishing?

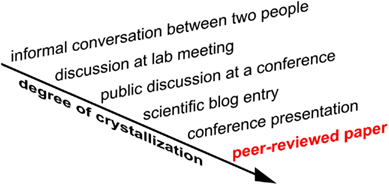

High-quality peer review of manuscripts submitted to ASHA journals is essential to maintaining and building the scientific foundation of our profession. I am reminded of the importance of our peer-review system whenever I encounter charismatic speakers at conferences or read articles in newsletters or on blogs that advocate for a particular type of treatment of a disorder but do not cite any solid studies published in peer-reviewed journals (such as JSLHR, LSHSS, AJSLP, or AJA) that would support the speaker or writer’s positon. Often, the ideas expressed in these non-peer-reviewed venues have a passionate, testimonial quality to them that can make them dangerously appealing to busy clinicians charged with the responsibility of treating a client’s communication disorder. Upon encountering these non-scientific messages, I remind my students, “Don’t believe everything you hear or read. Look at the evidence. Are there any research articles that support that point of view?” Giving this advice to students, however, makes it even more important that we, as editors, reviewers, and authors, help to ensure that studies published in ASHA journals meet the highest possible standards for scientific rigor and research ethics. This can happen only when professionals are willing to serve as peer reviewers.

~ Dr. Marilyn Nippold, University of Oregon, Eugene. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools (LSHSS) Editor (2010–2012, 2014–2015).

What value does peer review add?

Without a rigorous peer review system, we would not be a science-driven profession, and any one opinion would be just as good as another. In reality, what we think is true may not necessarily be true, which is why it is essential that we conduct research projects that objectively test our hypotheses. And when it turns out that our hypotheses are not supported by the data, we need to accept that fact openly, attempt to understand what is really going on, learn from our findings, and become more enlightened about the topic.

~ Dr. Marilyn Nippold, University of Oregon, Eugene. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools (LSHSS) Editor (2010–2012, 2014–2015).

Further Reading: Background and General Guides to the Peer Review Process

Rennie, R. (2003). Editorial peer review: Its development and rationale [PDF]. In Godlee, F., Jefferson, T., (Eds.). Peer review in health sciences. Second edition. (pp. 1-13). London: BMJ Books. Available from www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-reviewers/training-materials.

Research Information Network. (2010). Peer review: A guide for researchers. Available from www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/communicating-and-disseminating-research.

Voice of Young Science. (2012). Peer review: The nuts and bolts. London: Sense About Science. Available from www.senseaboutscience.org/pages/publications.html.

Advice for Reviewers

What types of things do the best reviews accomplish?

The best reviews show an understanding of the author’s purpose in conducting the study and its potential value to the profession. Strong reviewers get to the point quickly by highlighting any fatal flaws. If none are found, and the study addresses an important topic and is well-conducted, the reviewer then makes concrete suggestions for improving the manuscript in a way that is objective, constructive, and respectful of the author.

~ Dr. Marilyn Nippold, University of Oregon, Eugene. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools (LSHSS) Editor (2010–2012, 2014–2015).

How many articles should a person review?

Sometimes people ask how much reviewing they should do. We all know it is our obligation. But it is time consuming and can be difficult, and who needs more of that?

What I think is that for every paper you submit for publication, you owe the universe two to three good quality reviews (because that’s what some poor associate editor had to scrounge up for your paper), plus one for the pot. So if you published two papers last year, you owe five to seven reviews to stay in karmic balance. If everyone followed this rule, it would make a lot of associate editors happy!

~ Dr. Jody Kreiman, University of California, Los Angeles. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research (JSLHR) Speech Editor (2012–2015)

Why should someone consider being a reviewer or reviewing more often?

Anyone who seeks to publish in ASHA journals should be willing to serve as a peer reviewer. Regular reviewers learn from others – including editors, authors, and fellow reviewers – and will gain insight into how to improve their own research and writing.

Another reason for participating in the peer review system is the realization that one is performing an essential service by helping to protect the scholarly reputation of our profession and in turn, helping to build a solid knowledge base in a particular area.

~ Dr. Marilyn Nippold, University of Oregon, Eugene. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools (LSHSS) Editor (2010–2012, 2014–2015).

What can a scientist do to increase his/her chances of receiving an invitation to serve as an ASHA Journals reviewer?

Update your ScholarOne Manuscripts account. Filling in your AJA, AJSLP, JSLHR, and LSHSS account details helps journal volunteer Editors and Associate Editors find you for review invitations. Please consider making sure your e-mail address, contact information, areas of expertise, and key words are all accurate by logging into your account and clicking your name in the upper-right-hand corner. Then select an area of your account to access and update.

The ASHA Journals ScholarOne Manuscripts platform also encourages each user to link an account to an Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) from within the same above-detailed account area. ORCID is a non-profit organization dedicated to solving the long-standing name ambiguity problem in scholarly communication by creating a central registry of unique identifiers for individual researchers and an open, transparent linking mechanism between ORCID and other current author identifier schemes. To learn more about ORCID, please visit http://orcid.org/content/initiative.

~ ASHA Journals Staff

What else do you think early career researchers should know about serving as a reviewer?

Everyone involved in the peer review process is on the same side – the side of the science. It’s not an adversarial process. Authors, editors, reviewers – we all want the science to shine as brightly as it can, and to advance human knowledge as far as we can, based on each data set we see. It’s not a competition. It’s about thinking as clearly and precisely as we can, as a team.

~ Dr. Jody Kreiman, University of California, Los Angeles. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research (JSLHR) Speech Editor (2012–2015)

* * * * *

When individuals serve as peer reviewers – volunteering their time, expertise, and knowledge to improve the research and writing of others – this can have profound implications for the health and wellbeing of the profession for generations to come.

~ Dr. Marilyn Nippold, University of Oregon, Eugene. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools (LSHSS) Editor (2010–2012, 2014–2015).

Further Reading: Tips and Tutorials for Reviewers

Callaham, M., Schriger, D. & Cooper, R.J. (2005). An Instructional Guide for Peer Reviewers of Biomedical Manuscripts. [Online Adobe Flash Tutorial.] Annals of Emergency Medicine. Available at http://www3.us.elsevierhealth.com/extractor/graphics/em-acep/index.html.

Cochrane Eyes and Vision. (2015). Translating Critical Appraisal of a Manuscript into Meaningful Peer Review. [Online Course. Requires Free Registration.] Available at http://eyes.cochrane.org/free-online-course-journal-peer-review.

Lucey, B. (2013). Ten tips from an editor on undertaking academic peer review for journals. Available at SSRN at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2331281.

Moher, D. & Jadad, A.R. (2003). How to peer review a manuscript [PDF]. In Godlee, F., Jefferson, T., (Eds.). Peer review in health sciences. Second edition. (pp. 183-190). London: BMJ Books. Available from www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-reviewers/training-materials.

Vintzileos, A. M., & Ananth, C. V. (2010). The art of peer-reviewing an original research paper: Important tips and guidelines. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 29(4), 513-518. Available from www.jultrasoundmed.org.

Current Issues in Peer Review

What are some of the current issues and debates surrounding the peer review process in scholarly publishing?

Current issues being debated are not only whether the peer review system is fair (unbiased) and reliable, effective in assuring quality and integrity, but also whether it is capable of detecting misconduct. Specific questions addressed in the literature are whether reviewers are adequately prepared to conduct quality reviews, whether reviewers respect the tenets of confidentiality, and whether reviewers understand the intellectual property rights of those who created the original works under review (e.g., grant proposals, prepublication manuscripts; Cowell, 2000; Macrina, 2005c; Martinson, Anderson, Crain, & de Vries, 2006). Some commentators question whether editors and associate editors are free of conflicts of interest; that is, whether they are impartial regardless of the source of manuscripts from institutions, industries, and authors (Haivas, Schroter, Waechter, & Smith, 2004; see also DeAngelis, Fontanarosa, & Flanagin, 2001).

An additional question is whether reviewers conduct their work according to defined standards. Wagner et al. (2003) suggested that the current review system lacks both objectivity and standardization (see also Steinbrook, 2004). Jefferson, Wager, and Davidoff (2002) identified desirable outcomes of peer review, namely, that the product is “important, useful, relevant, methodologically sound, ethically sound, complete, and accurate,” but noted, “surprisingly little is known about its effects on the quality and utility of published information, much less about its beneficial or adverse social, psychological, or financial effects” (p. 2787). In a recent review of 28 studies, Jefferson, Rudin, Brodney Folse, and Davidoff (2007) found no clear benefit of reviewer and/or author concealment, referee training, or other factors on publication quality, although methods of standardizing the review process received some support in two studies.

~ From Horner, J. & Minifie, F. D. (2011). Research Ethics II: Mentoring, Collaboration, Peer Review, and Data Management and Ownership. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 54(1), S330-S345.

Further Reading: Ethical Guidelines and Ongoing Debates

Committee on Publication Ethics. (2013). Ethical guidelines for peer reviewers. [PDF] Available from http://publicationethics.org.

Council of Science Editors. (2012). White Paper on Publication Ethics. Available from http://www.councilscienceeditors.org.

Nature. (2006). Nature’s peer review debate. [Links to 22 articles.] Available from http://www.nature.com/nature/peerreview/.

Rockwell, S. (2011). Ethics of peer review: A guide for manuscript reviewers. [PDF] Available from http://ori.hhs.gov/yale-university.