The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Read the Program Announcement

A lot of the fear and anxiety that comes with grant submissions is really the amorphous nature of the task. There’s so many different pieces. Part of what I’m trying to do in the next 7 to 12 minutes, is to demystify the process a little bit, the logistics.

A lot of the fear and anxiety that comes with grant submissions is really the amorphous nature of the task. There’s so many different pieces. Part of what I’m trying to do in the next 7 to 12 minutes, is to demystify the process a little bit, the logistics.

You have to read the program announcement really carefully. And I apologize for this. I don’t know why I feel obligated to apologize, but I’m telling you that you have to do something that’s very painful. Reading the program announcement is brutal. But you probably have to read it multiple times, and very carefully, and different sections at different times. You really have to comb through this and look very carefully for the information that matters.

There are some things in here like review dates, of course. There is application and submission information. Agency contacts. There’s all kinds of things in here. Eligibility information. This is the stuff that really matters about the award that you’re interested in. Don’t do this late in the evening. Do this when you’re really fresh and you can stand some serious bureaucratese. Because it’s been very, very carefully written and vetted by a lot of people. It’s what governs the mechanism, and it tells you what to do. When you make mistakes, it’s because you didn’t read the program announcement.

Every round we send back applications that don’t comply with these different administrative requirements. The font size is too small, the margins are too narrow, or the person is not eligible, or their institution is not eligible. Or something horrible—they put in too much appendix information. Just horrible things happen, and you send the thing back unreviewed, and it’s just because they haven’t read the program announcement.

The program announcement will include review criteria, for example, for a special award. The review criteria will be listed, and those go as specific instructions to the reviewers that they have to respond to. So it’s good if you know what they’re going to be asked. That works in your favor.

Get started early downloading application materials so you know exactly what the task is.

And you might as well start paying attention to what the technical issues are, and what all these ridiculous acronyms are. I hate these, but you might as well start learning what they are because that’s the way people are going to talk to you, when you talk to your program officer, they’re going to use all these kinds of acronyms. And you have to be up to speed knowing what the heck they mean. Especially the ones that refer to the mechanism that you’re after.

And you might as well start paying attention to what the technical issues are, and what all these ridiculous acronyms are. I hate these, but you might as well start learning what they are because that’s the way people are going to talk to you, when you talk to your program officer, they’re going to use all these kinds of acronyms. And you have to be up to speed knowing what the heck they mean. Especially the ones that refer to the mechanism that you’re after.

Get Organized Online and at Your Institution

There are things to do to get organized early on.

There are things to do to get organized early on.

Make sure you have an eRA Commons account. Most institutions will establish an eRA Commons account for you along with your new employee set up. But you want to make sure that’s been done. And they should let you know what your Commons ID is. You should log on and make sure everything is working. Your access to Commons is required.

Download the application guide, the program announcement. Identify your program officer—that should probably be at the top of the list.

Budget development and approval can take a long time. It’s not at all uncommon for it to take a month. You have people—there are never enough people working on grant budgeting. They can make your life really easy or really difficult, but the only way you know is to get started early. If that’s going to be a problem, you want it to be a problem that has plenty of time to be solved—not at the last minute. You can develop your budget well in advance of your narrative. You don’t have to wait until you’ve finished your grant for most budget offices to look at your budget. They couldn’t care less what your experiments are, they want to know how much it costs.

Make sure your institution is set up on Grants.gov. That could be really horrific. You want to make sure you’re all set all the way through the submission process.

Identify People to Help You Through the Logistics

The people you need to help you through the logistics. You need your next door neighbor at your institution who is an experienced grant writer. It doesn’t matter if they’re in an area that’s totally unrelated to yours. You just need someone who is well-experienced in submitting grants. You want to sit with them and walk through the logistics. And they’ll tell you who is going to help you and who is going to slow you down. And walk you through the process. You absolutely need that person. Don’t try to do this on your own, it won’t be automatic.

The people you need to help you through the logistics. You need your next door neighbor at your institution who is an experienced grant writer. It doesn’t matter if they’re in an area that’s totally unrelated to yours. You just need someone who is well-experienced in submitting grants. You want to sit with them and walk through the logistics. And they’ll tell you who is going to help you and who is going to slow you down. And walk you through the process. You absolutely need that person. Don’t try to do this on your own, it won’t be automatic.

You need your person who is an experienced grant writer in your area. This is a person who can look over your shoulder and say, “Yes, you’re on track. You should be doing this. This study section has this kind of involvement, and you have to watch out for these aspects.” You need that person as well.

Then you need a person who is right narrowly, perfectly in your sub-discipline—your mentor. Your scientific mentor and guide. You need that person who can look at your grant—and that person needs to be a grant recipient as well—and that person needs to read your grant in great detail and say, “Yep, that’s good to go.” You should not try to do this without having an experienced PI read your grant as carefully as you do. It’s just disastrous. In that 50% on the undiscussed list, there’s a shocking number of applications that have never been looked at by anyone except the applicant. It’s just—what were you thinking?

Make sure you have at least those three people working with you, in addition to your team. In addition to your team. So that person in your subdiscipline isn’t one of your team members. That’s an objective guide.

Then inside the grant, inside the grant budget. You can’t do this as a newbie. I’ll just say this again. You can’t do this by yourself. Don’t try. You will mess it up. Everybody will be mad. Don’t bother trying.

Then inside the grant, inside the grant budget. You can’t do this as a newbie. I’ll just say this again. You can’t do this by yourself. Don’t try. You will mess it up. Everybody will be mad. Don’t bother trying.

No one expects you to do it. This is not what you’re trained to do. You’re no good at it. I promise. You may be great at putting the experiment together and knowing what people you need. You may even be able to figure out all the money on your own. But don’t bother. There are people where that’s they’re job, and they’re happy to do that for you.

Budgeting Time for Grantwriting

When you’re starting to put this together, and you’re looking at the application, look at the things that take a lot of time. Because some of these things take a huge amount of time, and they depend on other people.

When you’re starting to put this together, and you’re looking at the application, look at the things that take a lot of time. Because some of these things take a huge amount of time, and they depend on other people.

The things that depend on other people—get those going early, because other people will never respect your deadlines. Give them a deadline that is courteous to them. Give them a month to give you their biographical sketch. Something that is going to take them 20 minutes. It might take them 10 seconds because they already have it, but you want them to write a nice personal paragraph, so you give them an extra month. Give them a deadline that is well ahead of your deadline. So you don’t get this piece of junk that comes in and you get biographical sketches that are all in different fonts.

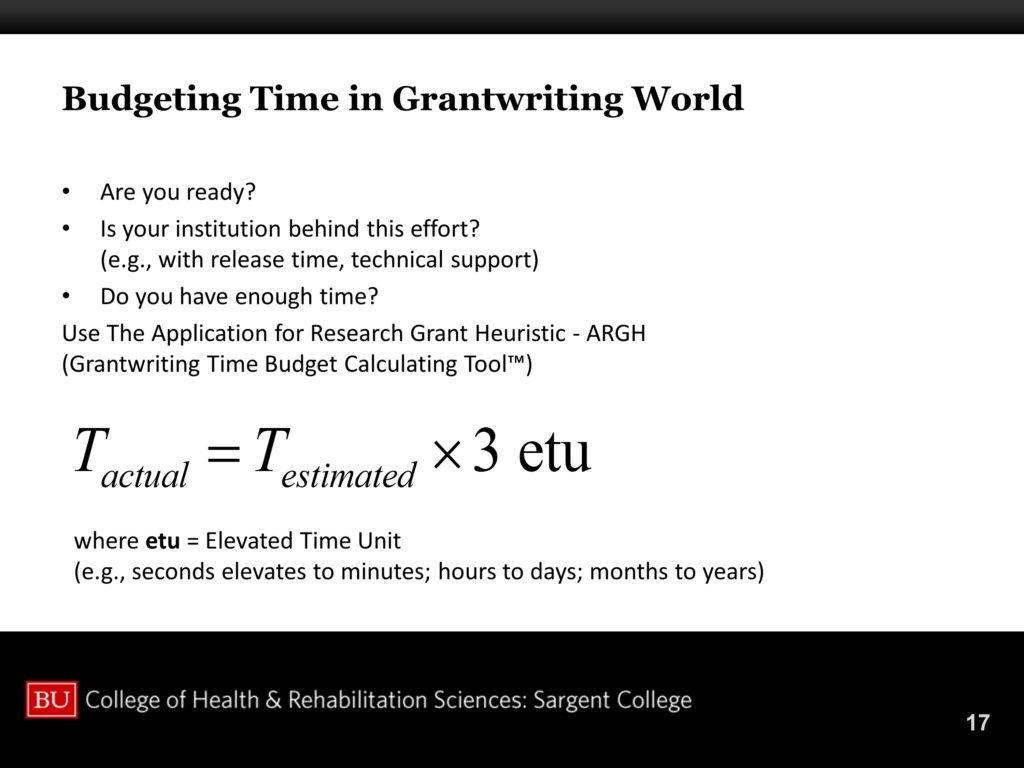

So, do you have enough time? This is actually my trademarked Grantwriting Time Budget Calculating Tool. Here it is.

You take the actual time you’re going to need to prepare your grant. You come up with your absolute best estimate. You say—I think this is going to take me three weeks. It’s never taken me more than three weeks to write 12 pages in my life. Three weeks is going to be awesome, really good.

So you multiply that by 3. Now you’re at 9 weeks. But then you have to convert that to the etu —the Elevated Time Unit. So you go one time unit up. If you’re at seconds, you go to minutes. If you have 9 weeks, then you’re actually at 9 months. And that is exactly right. You be sure to use this GTBCT and you will never run out of time, I promise.

This is accurate. This really works, as long as your estimate—as long as you are very real about your estimate. If you think it is going to take 9 months, then you are exactly right: 27 years.

Audience Comment: A lot of institutions have internal deadlines. So it’s not the deadline to the grant you’re looking at, it’s the internal deadline. So now you need to add time for the five day prior to going to the grants office, or the one-month prior to grant submission when it needs to be reviewed internally by your department.

I should put a k in there. You’re right. Plus k.

Audience Comment: You want to write it, put it aside, and come back to it in three months. And then when you re-read and say, “What the heck was I thinking?” and have to re-write it, then that is when you start your timeline.

Exactly. Allow plenty of time. That’s all.

Preparing for Your First NIH Grant: More Videos in This Series

1. Who Is the Target Audience for Your Grant?

2. How Do I Determine an Appropriate Scope, Size, and Topic for My Research Project?

3. Common Challenges and Problems in Constructing Specific Aims

4. Are You Ready to Write Your First NIH Grant? Really?

5. Demystifying the Logistics of the Grant Application Process

6. Identifying Time and Budgetary Commitments for Your Research Project

7. Anatomy of the SF424: A Formula for NIH Research Grants

8. Common Strengths and Weaknesses in Grant Applications