The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

It is such an honor to be asked to come back to such an important conference. It really was career changing for me to attend Lessons for Success. So, to be back here, as a successful person is so wonderful. So thank you for inviting me. I’m so glad to be in this spot.

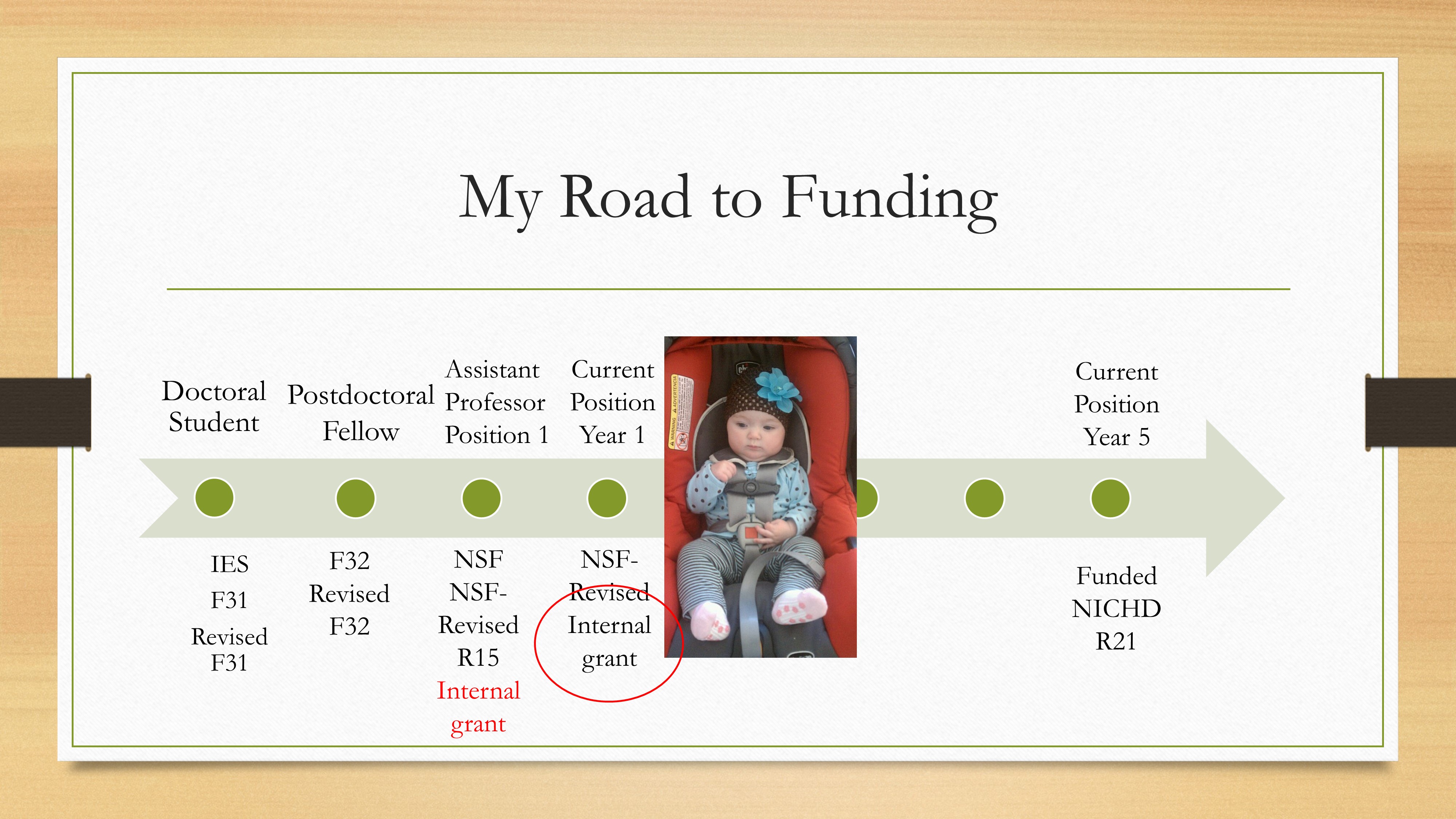

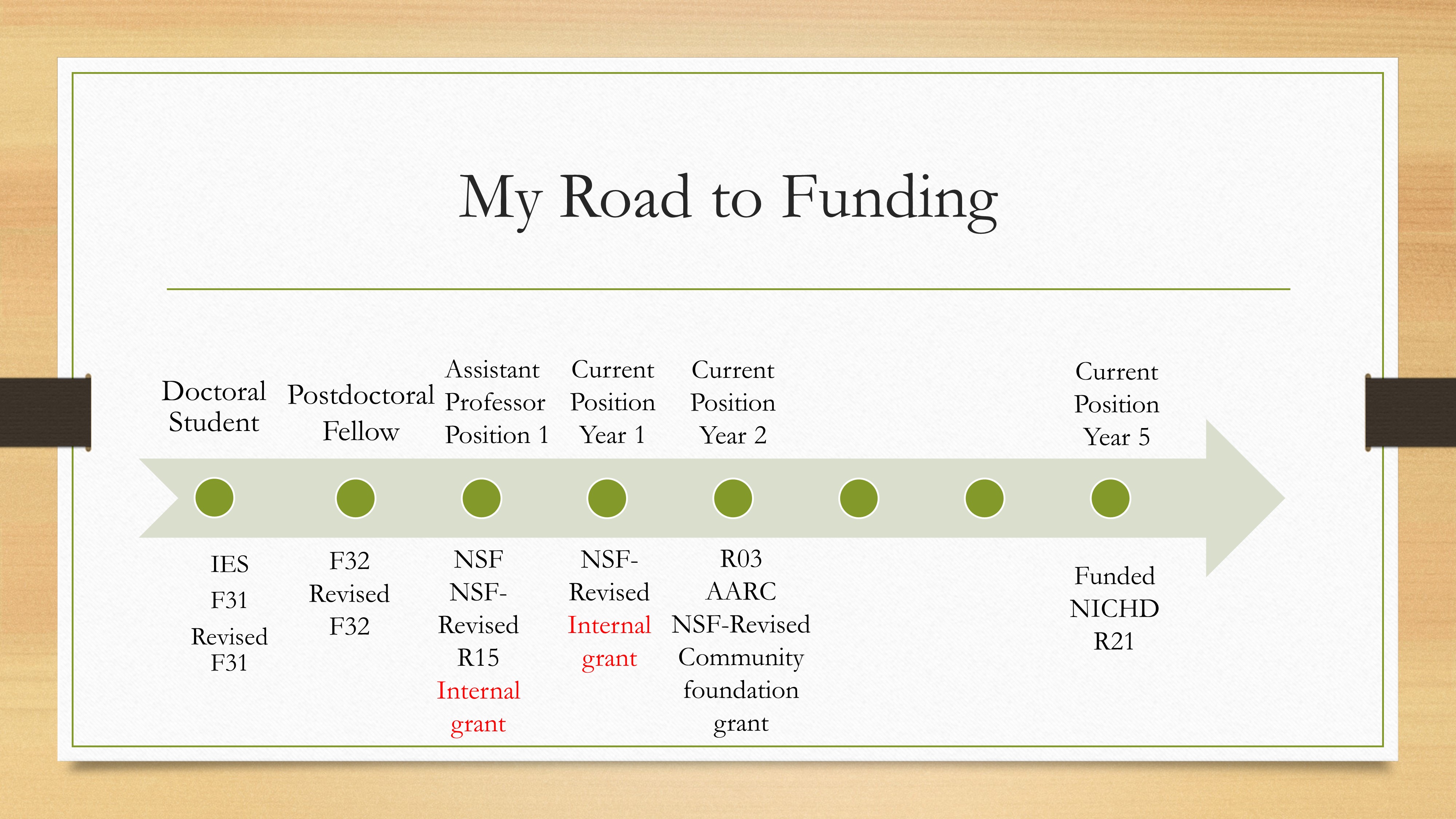

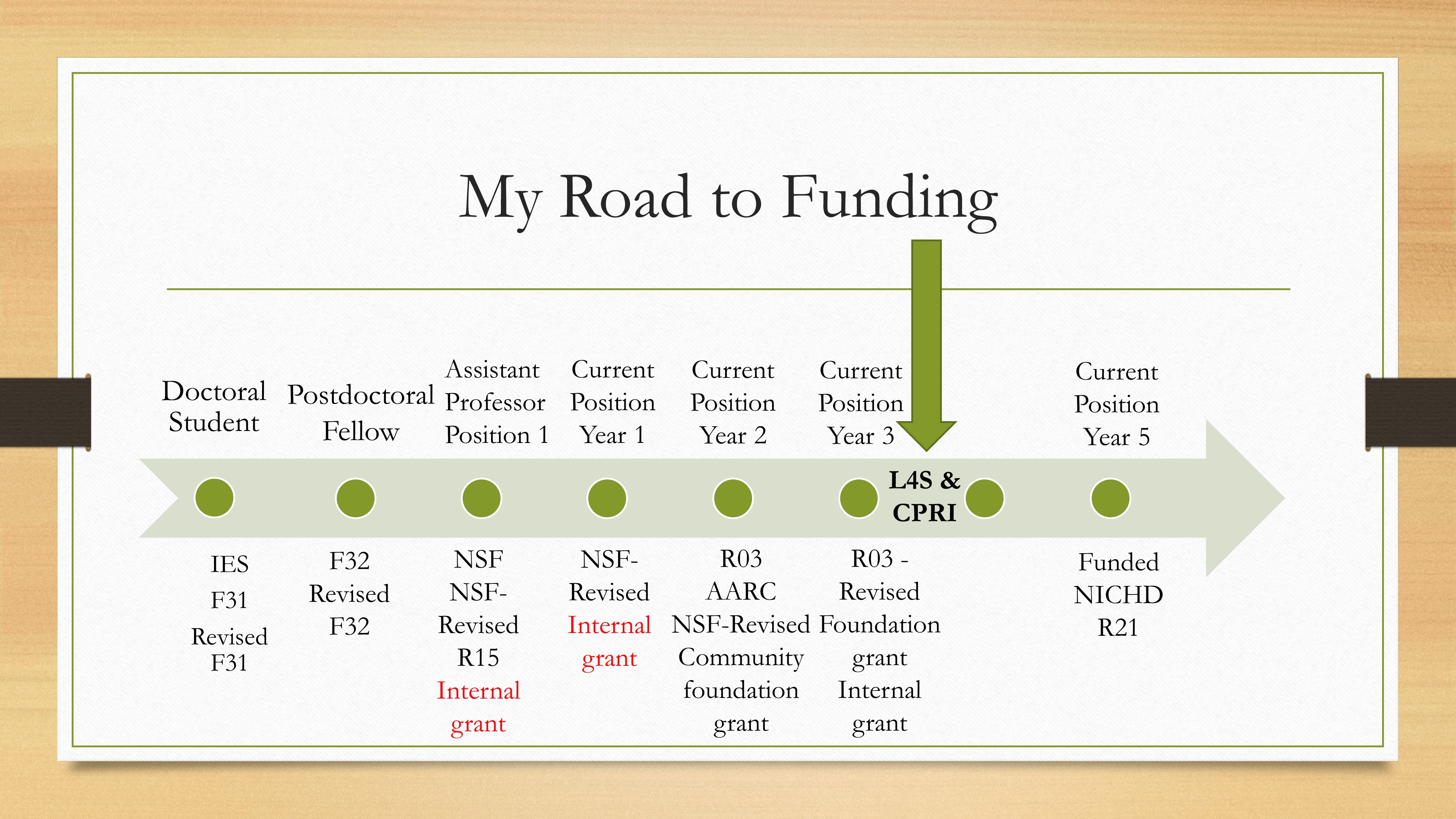

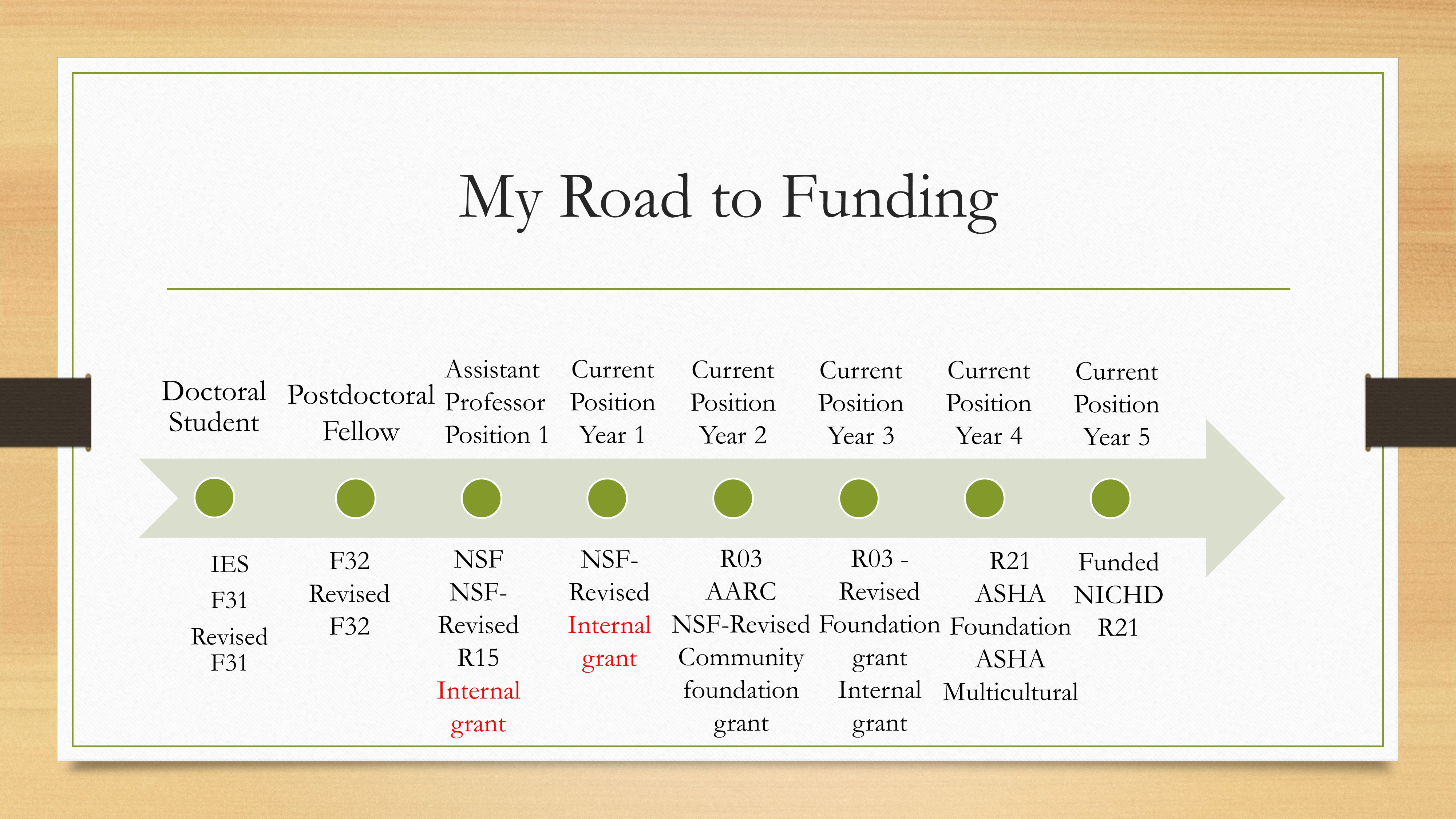

My Road to Funding

My funding trajectory has been a little bit more protracted than other people’s have been. I’m going to explain to you a little bit about why that is. I’ve been doing a lot of multitasking in the past five years.

I started submitting NIH grants when I was a doctoral student. I just received my first NIH grant this past spring. It’s been a long and winding road. But I’m going to tell you a little bit about my path and what I’ve been doing.

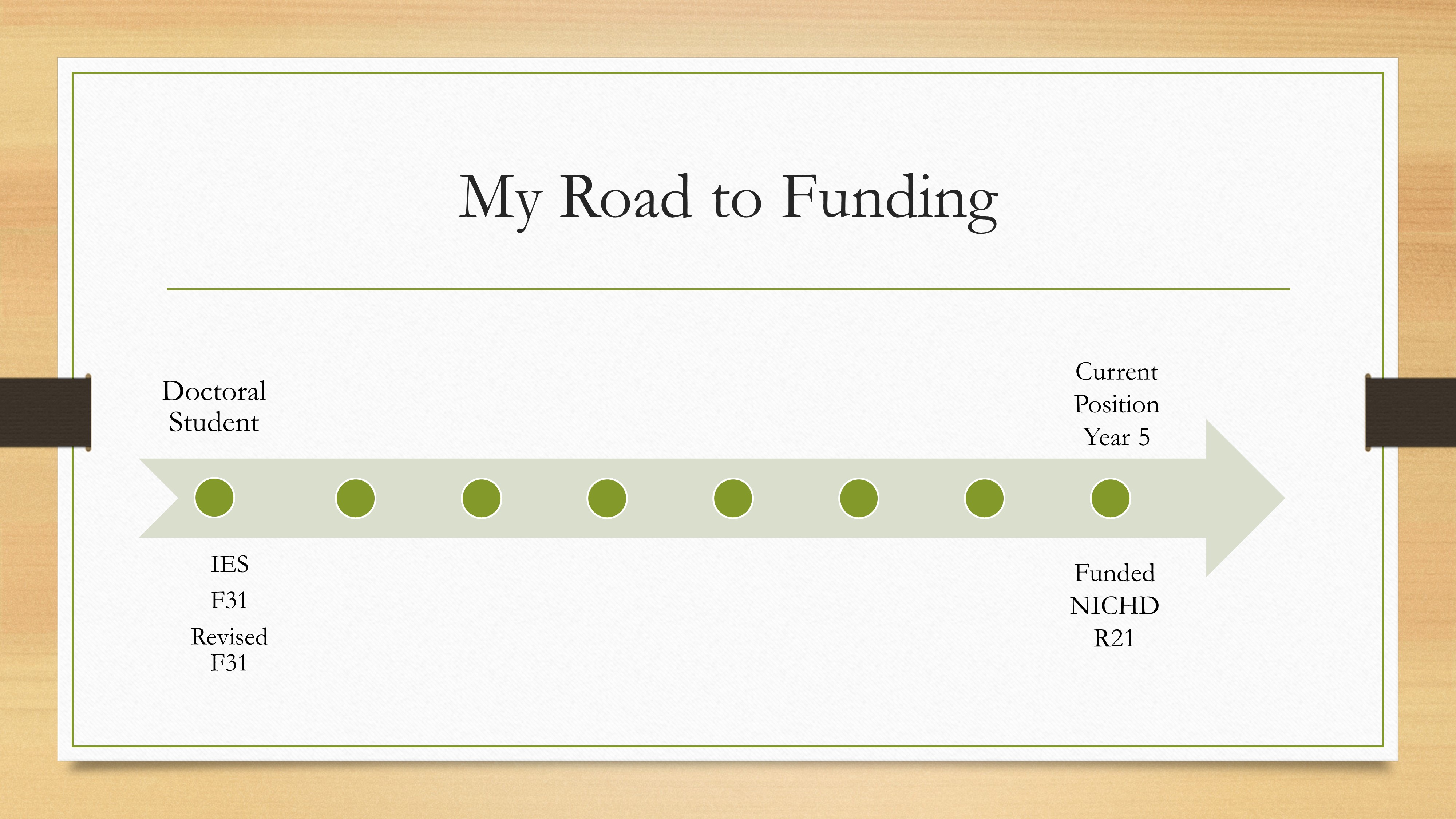

When I was a doctoral student, I submitted an IES grant looking at bilingual literacy, an F31, and a revised F31. None of those were funded.

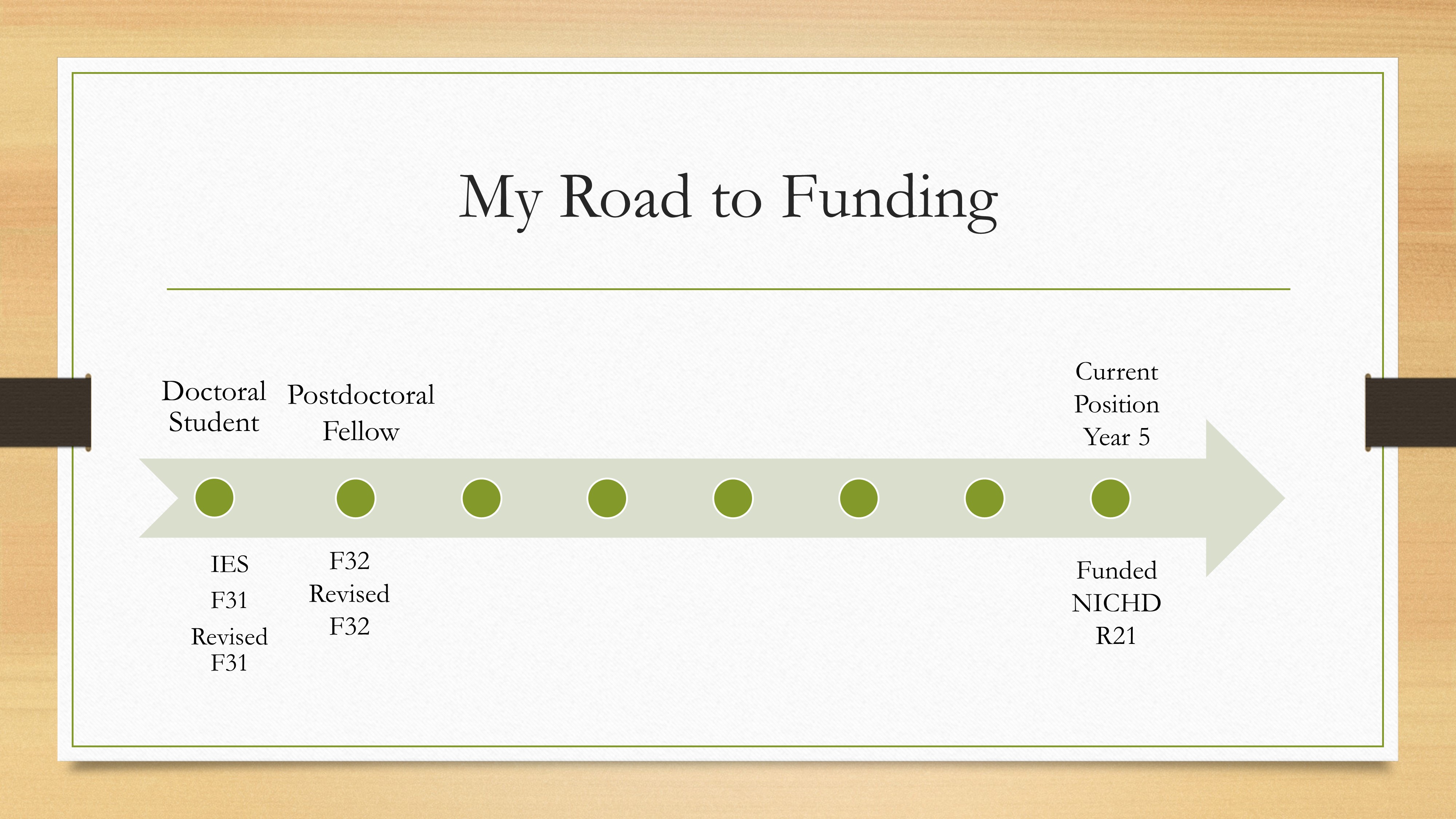

When I was a PhD student, when I was about to start my postdoc, I submitted an F32 award which was scored. Then I revised it and it was not discussed.

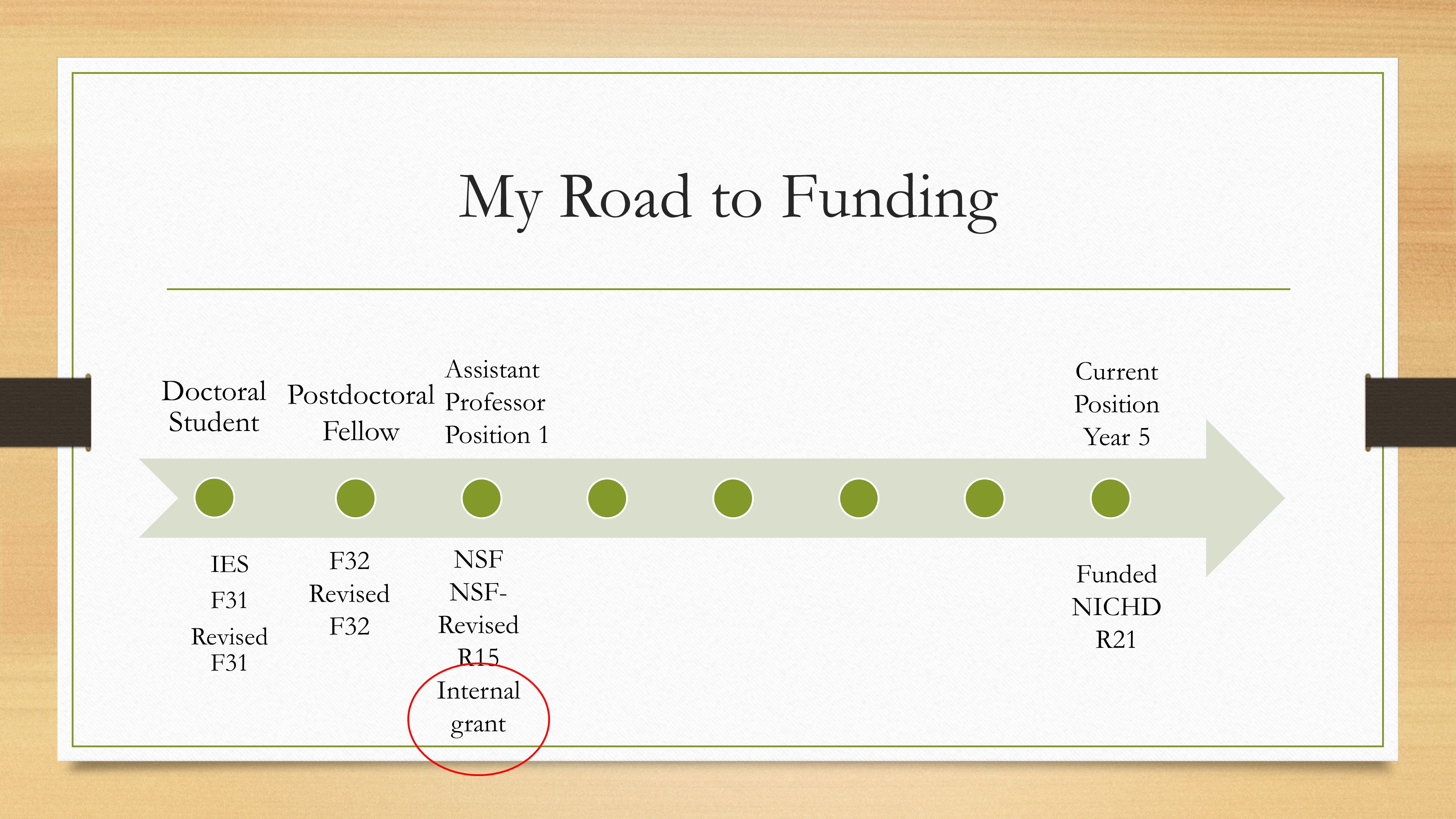

Then, I finally hit something. In my first assistant professor position, I applied for an internal grant, and I got that. So that was good.

Looking back, I’ve had people give advice saying, “Apply for the small grants first, then build up to the large grants.” I did that a little bit backwards. I applied for some big ones, without some small ones. But I ended up getting a small internal grant which allowed me to transcribe and analyze some data to help me apply for some bigger grants. I also applied for an NSF grant, and an NIH revised R15 — or I submitted an R15, then revised it. Neither of those got funded.

I kept on keeping on. And, oh. I had a baby.

That’s part of the reason why things slowed down a little bit. When I started my current assistant professor position, I had a six week old. I actually submitted an NSF grant two weeks after she was born. One-handed. I had a baby in one hand, and I was doing the budget for the NSF grant with the other hand. I was in New York, but I was applying through the Arizona-sponsored projects because I hadn’t moved yet. Sometimes I wish NSF and NIH could see what’s on the other side of the person submitting, because it’s often a little bit crazy. It’s a little crazy to submit an NSF grant with a two-week old, but I think we’re all a little crazy, so.

Anyway, the first year I was at the University of Arizona, I got another internal grant. I got a nice faculty seed grant, which helped me collect some data. Which was really great.

I continued applying. I applied for an R03. I applied for an AARC award, I revised the NSF grant and submitted that again, and I applied for a community foundation grant. And I didn’t get any of them.

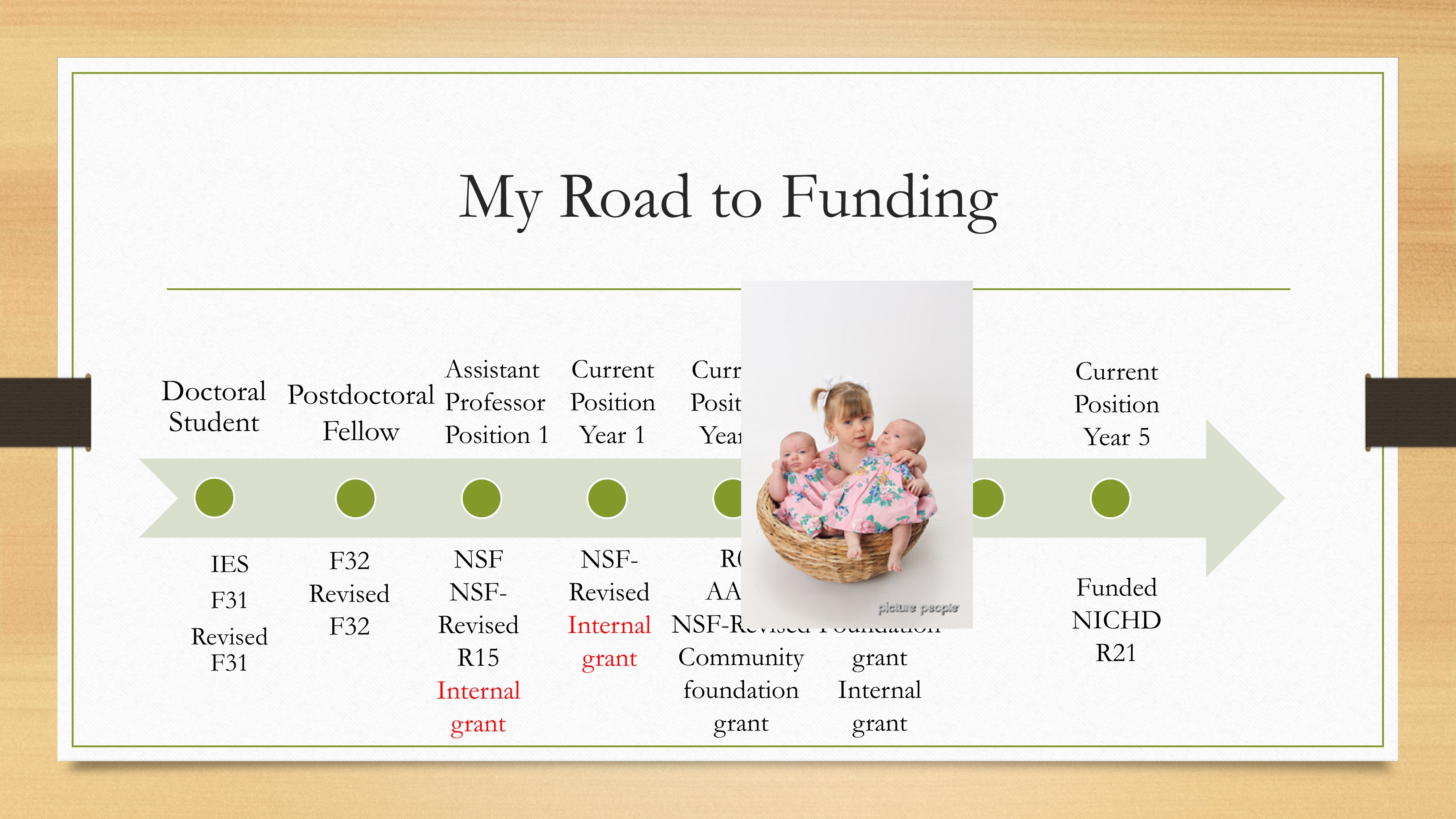

So, you’re failing at grantwriting, Leah, why not add twins? So then I had three little kids.

Then I came to Lessons for Success, and I got to do CPRI, too. All in the same year. Literally, that changed everything for me. It was like a lightbulb went off, and I thought, “Oh, that’s what they want.” I remember hearing Holly Storkel present on Specific Aims and I said, “Oh, that’s the way you do it, I see now.”

Having that input, and also mentoring from Lisa Goffman and Lisa Bedore also helped me. Lisa Bedore was my mentor for CPRI. Lisa Goffman was my mentor for Lessons for Success. Having their input was really fundamental to being successful.

I submitted an R21, an ASHFoundation and an ASHA Multicultural Award. The R21 got scored on the first round. It wasn’t fundable, but it was scored. That was like my in, and I thought, “Okay, now I just need to drive it home.”

With a lot of help, specifically from Elena Plante and some other people — it got funded on the revision.

So, long road, right? And lots of rejections. There were times I started having some existential crises. NSF and NIH have both made me cry at different times. I think a lot of times I would get to the point after so much rejection that I thought, maybe I shouldn’t be doing this. Maybe I should be doing something else in my life. What am I doing? But really, just pressing through that made all the difference to me, to just keep going.

What I Learned

So, what are some lessons that I learned?

Be humble.

This was a tricky thing. It’s a hard thing to do. But one of the things that I did, that really made a difference to me, was to ask for help from people in my department. Lay it all on the line, show your work, and say, “Tear it apart.” And just take the feedback, take the criticism.

Know that the only way you’re going to move forward is if you listen to the people who know what they’re talking about. I called it “remedial grant help” — I did a presentation of my specific aims, and then everybody tore it apart. But it made all the difference. Because the suggestions were good, and they were right on. It was people from different areas of the field that could look at my work in different ways, and give me some really specific things to do. That really changed it, that really made it accessible to a lot of people. So be humble. Take constructive criticism well.

It takes a village.

I had feedback from so many people: Kate Button, Brad Story, Edwin Maas, Gayle DeDe, Elena Plante, Pelagie Beeson, Steven Wilson. All of these people gave me feedback on my grant. People in other departments, in other universities. Laida Restrepo at ASU.

Get a lot of eyes on it — but then, know when to be with your work by yourself and make your own decisions. Brad Story gave me a really nice bit of advice. He said, “You’ve gotten a lot of feedback from a lot of people. Now, what do you think? Do you want the theory in there, or not? Do you want this in there, or not?” And he really said, “Take it back.” After you’ve got a lot of input, take it back and say what do you want to do.

When you’re going through hell, just keep going.

Honestly, just keep going. After you’ve gotten rejection after rejection, after rejection — and for me, I had these little kids at home, and I thought, “Oh my God, what am I doing, this is crazy. Am I ever going to make it?” Just keep going. Because if you keep trying and you keep at it, sooner or later something is going to come through for you.

You belong in this profession.

This is really just my internal workings. But even when people reject you and reject you and reject you, sometimes it’s just the way that you’re pitching your work. It’s not that you don’t do good work, or that you don’t belong. It means you need to find another pathway to communicate what you do in a different way.

Dig deep.

This is something I learned: Nothing gets by the review panel. Nothing.

When I did my revision for my R21, it’s the deepest that I ever dug in my theory and in my approach. I had to take it to a level that I’ve never taken my research to before. Because the review panel will catch it if something’s not detailed, if something’s not defined, if you gloss over something, they’re going to catch it.

Nothing half-baked.

There are only two chances when you put in an NIH grant to get it funded. Don’t waste one of those chances with something that’s half-baked. Make sure what you put in the first time is absolutely as perfect as it possibly can be. You don’t want to put it in and say, “Oh, then I’ll get the feedback and revise it.” No. You only have two shots. And from my experience, you need to get a score on the first shot to get it in the second time. I know there are people who have gone from non-discussed to funded. But I was never one of those people. Don’t waste one of your chances. Make sure what you put in the first time is excellent.

And trust yourself.

Like I said, it’s good to get feedback from other people, but you’re an expert in what you do. Trust yourself, too, instead of always wondering, “What do they want, what do they want?” Think about what you think is the best way to approach this. What do you think is the best theoretical model? Trust your own perspective on your work as well.

Questions and Discussion

That’s it. I don’t know if we’re taking questions or not, but I put a questions slide in. Are there any questions?

Question: Can you talk a little bit about the challenges in balancing the theoretical linguistics piece with the applied clinical piece of your grant?

One of the big pieces of the review that I hadn’t thought of was adding a psycholinguist onto the grant. That was really integral to it. Suzanne Curtin, the psycholinguist, really helped me sit down and formalize how I was going to see my outcomes happen. I don’t think I could have done it without her.

She really helped me think things through. This is what I mean by digging deep. She helped me dig to a level I wouldn’t have gone to, if I hadn’t collaborated with her.

That was based on a reviewer comment, and doing that really ended up making a big difference in my theoretical model. Big time. So it was a great suggestion.

Also, I had submitted to NIDCD, but it got bumped to NICHD. The panel on NICHD was much more theoretically oriented in some ways, so I needed that piece to meet the demands of that particular panel.

One of my big struggles with NSF was that it was cross-reviewed by developmental learning sciences and linguistics. I did my postdoc in theoretical linguistics and theoretical phonology with Jessica Barlow at UCSD. I knew the grant was going to get reviewed by the linguistics panel — but I don’t know that it went over so well with developmental and learning sciences. It was difficult to balance what theoretical linguistics wants with the more applied piece in the developmental and learning sciences. So that was difficult, I think, that cross-review. Even though it gives you more of an opportunity to be funded, that was a challenge for me.

Whereas NIH was so much more straightforward for me because the clinical piece is so easy to define for what I do. The significance for me, and the innovation, is kind of a piece of cake. It’s more the approach I need to get hammered out. For NIH, it was easier with the more medical-type of language. NSF was really a challenge for me. I don’t have an answer of how I balanced it for NSF, because I don’t think I did, because I never got funded.

Question: How did you get so many people to look at your grant? Were you worried about depleting your pool of potential reviewers? And how did you come up with the idea for your “remedial grant help”?

What I did was I first sent the specific aims out to four or five people, integrated the feedback, and then tried to hammer them out as well as I could before I even dealt with anything else in the body of the grant.

Then, the body of the grant, I sent to different people. Because I didn’t want to tire out people with all my stuff. So, I would pick and choose different people with different pieces of it.

I didn’t think of the fact that I might be losing potential reviewers. Because most people I sent it out to were people in my department, so they’d have to recuse themselves anyway. But that’s something to consider.

As far as my remedial grant help, I think I just said at one point, “If I want this to happen, this is the process I need to go through. If I want to get funded, I need to present my work and have everybody tear it to shreds. And I’m just going to have to do that.

To me, getting funded trumped everything. If it came down to people thinking that I was stupid or something, I was like, “I don’t really care, as long as I get funded.” That was my goal. Anything else that had to happen, was going to happen.

Question: You had mentioned that your experience at Lessons for Success and CPRI was a game-changer. I was wondering if you could share with us a couple of the nuggets that you learned or some of the misconceptions you were able to put to rest.

One of the things that I learned, that came up right away, was that one of my specific aims depended on the other specific aim. That was a big no-no. That came up at CPRI. I think Margaret put mine up first, and I was the most junior person there, so talk about feeling not so bright. You have your specific aims up, and one depends on the other. And everyone right away is like, “Oh, number 2 depends on number 1, you can’t do it that way.” That was kind of my start to hammering things out, “Okay, how do I conceptualize specific aims? What belongs in there?”

Like I said, Holly gave a presentation at Lessons for Success a month later, and that clicked in. Once I clearly delineated what my aims were, everything else fell into place.

When I had gotten all my reviews back on all those grants that I didn’t get, they always had problems with the approach, it was always the approach, it was always the approach. I was really having a hard time with, “What is it about my approach that people just aren’t understanding?”

What it was, was that I needed to really link each stage of my approach with the specific aims. Once I had those aims hammered out, it was easy. I was like, “Oh, yeah. This is this aim. And this is this aim.” But I had never conceptualized it like that before. All of a sudden, I had an approach that reflected what I was trying to do. That really was what my problem was, all that time. That was the big one that stood out for me.