The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

In my department, when we have junior faculty — which we almost always do have junior faculty — each person is assigned a mentor, and the chair also serves as a mentor. There are various points in time where the mentor and the chair huddle up and say, “How are things going?”

Some of these things on my list are things various faculty have reported about various junior faculty where they say — this person is doing really good. Here’s what I’m seeing.

This will give you an idea of some of the thing people might be looking for.

Research

Starting with research. Some of the things that get reported in these conversations are thing like:

How soon are you purchasing major supplies that are central to your research program? If you’re not purchasing it, you’re not doing your research.

How soon do you start collecting new data?

How soon do you publish your dissertation or postdoctoral work? Many of you are probably still sitting on that dissertation. Let’s get it out.

How soon do presentations turn into publications?

Successful people create a research pipeline.

All of this relates to the importance of having a research pipeline. You have to have multiple projects that are in various points of their development.

There should be some studies that you’re thinking about. Some studies that you’re actually really working on, and getting the methods up and running. Ones that you’re collecting data on.

And then, even once you have that data, you need to be pushing it out to dissemination. This is one of the biggest challenges, is making sure you’re getting your work out there. It’s important to get those publications to set up your next grant application, to keep your work in the public eye so you’re building your reputation in a particular area.

When you’re thinking about your research pipeline, you want to be thinking about both activities as well as actual products you can point to on your CV and your grant applications.

Creating Products

Here are some issues about creating products. When my son was in kindergarten, he had a writing curriculum called “Writing without tears.” I thought, “Oh, this is what I need!” It turns out it was just about handwriting, so it wasn’t really that helpful, but I think we need something like that for academics. There are a number of resources shown here on the slides. Basically, most of these resources talk about setting aside time to write, writing every day, and really making writing a habit.

Elena talked about grantwriting as something she does every day — it’s not a special event. It’s the same thing with manuscript writing. It shouldn’t be a special event in your life, it should be something that your regularly do.

Research

Some other things to look at:

- How soon do you apply for internal funding?

- How soon do you apply for small-scale foundation funding?

- How soon do you apply for larger-scale national funding?

- Are you taking advantage of training and mentoring opportunities related to funding?

Successful people have a strategic plan.

All of this relates to having a strategic plan. I was talking to one of our junior faculty the other day, and he had a really clear plan of, “I’m going to apply for this grant, and that’s going to fund these studies, and then I’m going to apply for this grant and that’ll fund these other studies that are sort of related, but a little different. And then all of these will come together to support my R01 application.

It was really clear that he was being thoughtful about the studies that needed to get done, the kind of funding he needed to be able to get those studies off the ground. And he had a plan on how those were going to lead to something bigger. It wasn’t just random funding here, random funding there, but pieces of work that were going to come together to make a cohesive whole.

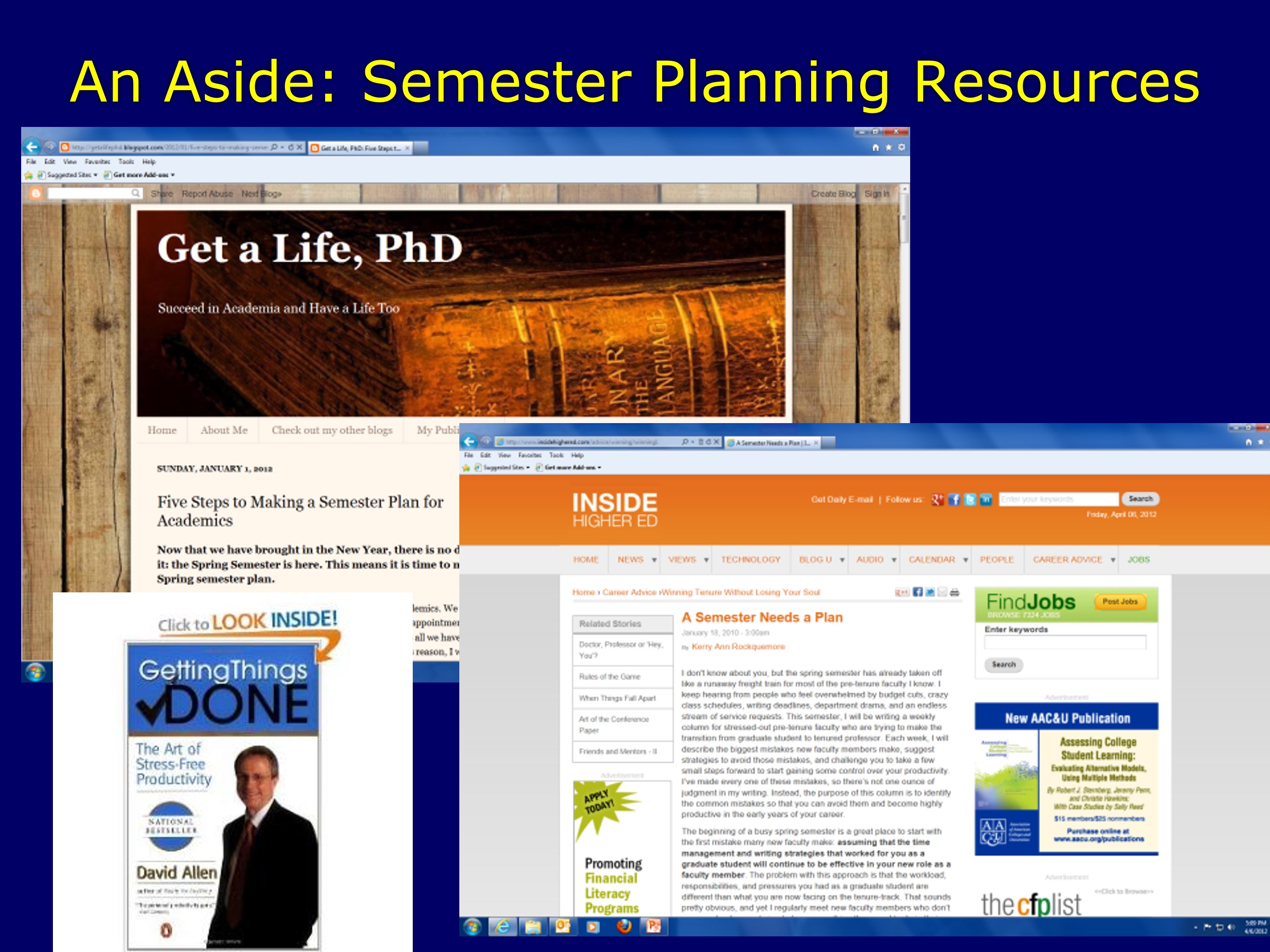

Semester Planning

This relates a little bit to just general semester planning. If I went to my office and just thought, well let’s see what I get done today, I promise you I would not be getting much done. Especially on the really important things.

In addition to thinking about having this kind of grant plan, you need to have a semester plan and thinking about all the things you need to get done.

Here are some resources for how you might go about building a semester plan, and some things you need to think about.

How quickly do you resubmit manuscripts after receiving reviews?

How quickly do you start work on a revised grant application after receiving reviews?

And how quickly do you move to a new journal or funding agency once you are rejected?

Successful people are resilient.

Everyone has said in the room — you’re going to write a lot of grants, many of them are not going to get accepted. You’re going to write a lot of journal articles, and many of them, people are not going to love the first time you put them in.

But what separates the successful people from the less successful people is successful people get over that rejection quickly and immediately move on to Plan B, or C, or D … or Z.

How quickly do you attract students at different levels to your project?

Do those student projects lead to presentations or publications?

How coherent are the projects across students?

Are you making use of student funding outlets, and are you retaining those students?

Successful people use student projects wisely

So what this relates to, is it’s great to work with students. Students are very fun to work with. That might be part of what drew you to this field to begin with.

But it’s really important that you harness their energy for things that are going to help you with your research goals.

Students should be part of research, not so much part of teaching. They will learn something, no matter what project you stick them on. So make sure you’re putting them on things that will help you out.

Being able to compete for some student funding can help diversify your funding portfolio. Definitely if you can retain your students, that’s going to be good for you. That’s one less person you have to train on something to do, and that’s going to make your lab a lot more efficient.

Teaching

Notice that I’ve talked a lot about research. I’m at an R1 institution, so research is what gets you tenure, honestly. You can be pretty mediocre at your teaching, and you’ll still get tenure. Some of you might be at places that have different kinds of criteria.

In general, this is a good discussion to have with someone at your university: of what are the markers of success? What are senior faculty looking for when they look at you? It might be a little bit different from what I’m presenting here, but either way, it’ll give you some guidance about how you should be spending your time.

So, in terms of teaching, are you going to copy your own exams? Are you running them to testing services? Are you grading every paper? Are you finding video clips and inserting clip art on your Powerpoint slides? Etc.

Successful people focus their teaching efforts and delegate effectively.

Successful people focus their teaching efforts and delegate effectively.

Successful people delegate responsibilities effectively, particularly around their teaching efforts. So think about who you can get to do some of these things. You don’t have to do everything when you’re teaching. Many other people can be involved.

Make sure you’re using your GTAs wisely. If you don’t have teaching assistants, or you don’t have enough TA time, look at who else you can use. You might have student office workers in our department. They can be copying your exams or running to testing services. Think about who can do the work so that you’re not doing some of the things that don’t have a lot of payoff.

You can also look at getting teaching grants. Teaching grants are a good way to help offload some of that teaching responsibility and preparation.

And remember, too, that “good enough” is just fine for the first offering of a course. It’s not to say that you should slack off in your teaching, but once again, students are going to learn from however you teach it — no matter how mediocre you are. Hopefully you won’t be striving for that. But there will be a lot they can take from the class, even if you don’t do it perfectly the first time. Then, you can improve on that year after year.

Hopefully, you’re able to teach your courses repeatedly across semesters. So, it doesn’t have to be perfect the first time. Whereas, you’re not going to do the same study over and over again until you get it right — or you’re not going to have very long longevity in the field. Just think about where you need to spend that time.

Service

Service: Do you say “yes” or “no” — or do you ask “What activities are required? What is the timeline for those activities? Can I get back to you on that?”

Successful people are thoughtful about their time.

Successful people are thoughtful about their time. You can’t say yes to everything. So you really want to ask questions when people ask you to do something. Think about how much time it’s going to take, what you’re going to get out of it. Is it something you’re going to enjoy, or does it sound horrible. Then choose accordingly.

Life

Successful people have one.

Successful people have a life. You’ll have to figure out for yourself exactly what that means for you, because people have different priorities in their life — whereas research, teaching and service is a little more similar across all of us. You should think about what the priorities are in your life, and make sure you take time for those things, too.

Successful people do take vacations. They do leave work early. They go out to lunch with colleagues, all of these other things.

Think about the things you want to do that enhance your enjoyment of life and make sure you include those in your plan as well.

Resources on Work Life Balance

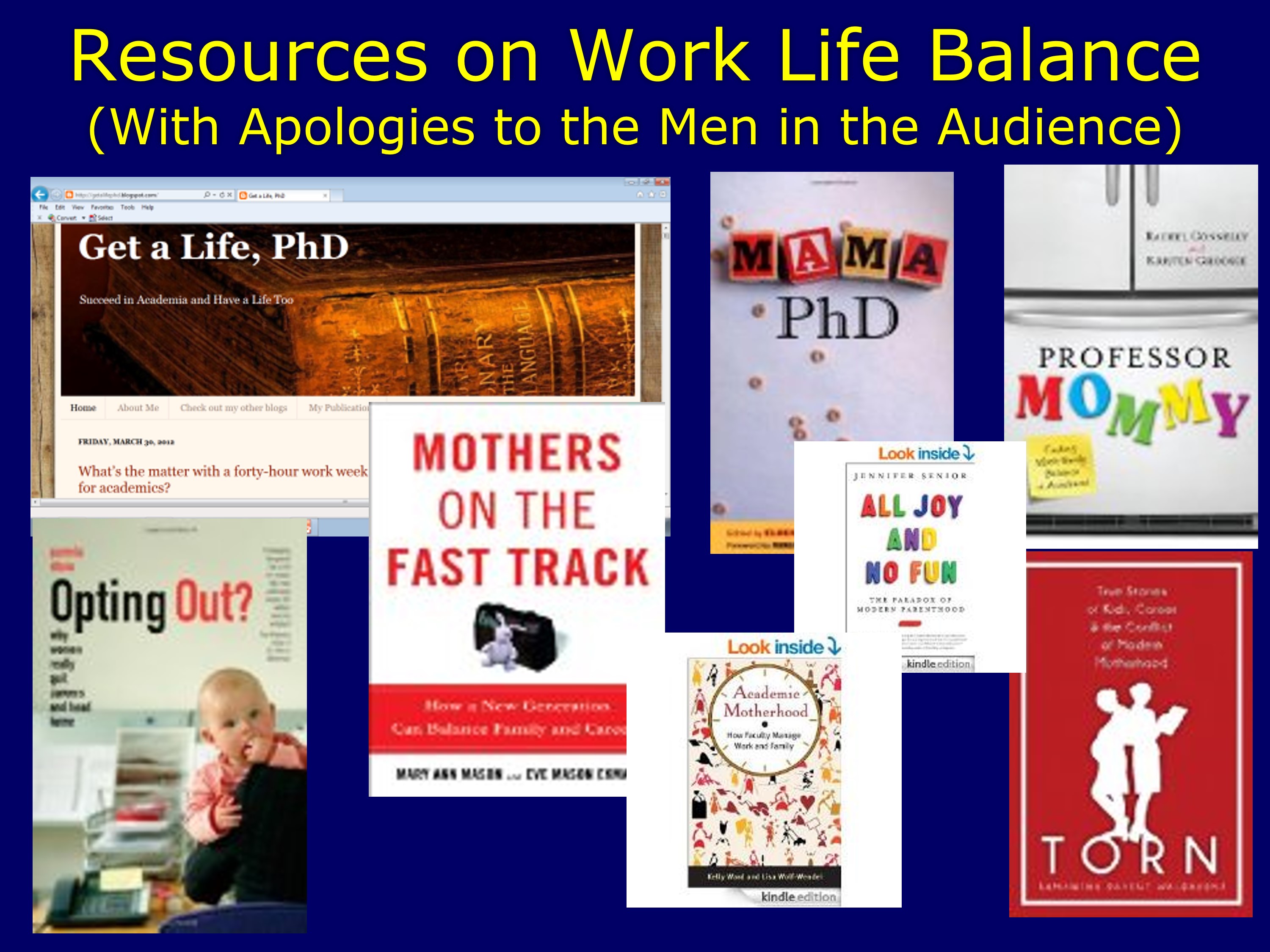

Here are a lot of resources on work/life balance. Most of them are aimed at women, so apologies for those of you who are male in the audience, you obviously all need to band together and write your own book. But you might get something out of these as well.

Further Reading: Writing Without Tears

Bolker, J. (1998). Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day: A Guide to Starting, Revising, and Finishing Your Doctoral Thesis. Owl Books.

Golash-Boza, T. (2011a). How to enhance your writing productivity with a Pomodoro timer. Get a Life, PhD. Available at http://getalifephd.blogspot.com/2011/10/how-to-enhance-your-writing.html

Golash-Boza, T. (2011b). How to become a better, faster writer. Get a Life, PhD. Available at http://getalifephd.blogspot.com/2011/07/how-to-become-better-faster-writer.html

Golash-Boza, T. (2012). Ten ways to write every day. Get a Life, PhD. Available at http://getalifephd.blogspot.com/2012/01/ten-ways-to-write-every-day.html

Silvia, P. J. (2007). How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing. American Psychological Association.

Further Reading: Semester Planning Resources

Allen, D. (2002). Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. Penguin Books.

Golash-Boza, T. (2012). Five steps to making a semester plan for academics. Get a Life, PhD. Available at http://getalifephd.blogspot.com/2012/01/five-steps-to-making-semester-plan-for.html

Rockquemore, K. (2010). A semester needs a plan. Inside Higher Ed. Available at https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/winning/winning1

Further Reading: Work Life Balance

Evans, E., & Grant, C. (2008). Mama, PhD: Women Write About Motherhood and Academic Life. Rutgers University Press.

Ghodsee, K., & Connelly, R. (2014). Professor Mommy: Finding Work-Family Balance in Academia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Golash-Boza, T.. (2012). What’s the matter with a forty-hour work week for academics?. Get a Life, PhD. Available at http://getalifephd.blogspot.com/2012/03/whats-matter-with-forty-hour-work-week.html

Mason, M., & Ekman, E. M. (2008). Mothers on the Fast Track: How a New Generation Can Balance Family and Careers. Oxford University Press.

Senior, J. (2015). All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenthood. Ecco.

Stone, P. (2007). Opting Out? Why Women Really Quit Careers and Head Home . University of California Press.

Walravens, S. P. (2011). Torn: True Stories of Kids, Career & the Conflict of Modern Motherhood. Coffeetown Press.

Ward, K. (2012). Academic Motherhood: How Faculty Manage Work and Family. Rutgers University Press.