The following is the presentation text, edited by the presenter for clarity.

My Path

Before I attempt to give any ‘tips’, first I’m going give you a little background on who I am and where I’m coming from, and why I’ve made some of the decisions I been making.

I did my PhD in Boston, and now I’m back there as an assistant professor at Boston University. My studies were through a speech and hearing biosciences technology program, a program originally designed to teach engineers to be speech and hearing scientists.

During my time, I worked at the MGH voice center. Four out of my five years as a doctoral student, I was funded on a T32, and I had no idea what writing a grant meant. I wrote a dissertation proposal, which is nothing like a real grant. I wasn’t really encouraged to write an F31, because we had four years of T32 funding. Plus, I was in a funded lab, and they only had to fund me for one year. It seemed like a waste of time to write a grant.

Honestly, I know that sounds ridiculous, but it seriously never occurred to me. I thought about it a little, just before I finished because I was looking for a postdoc. Potential mentors were asking me if I had grant writing experience, which I definitely didn’t. Luckily for me, I found a position at the University of Washington anyway. I was actually on a T32 again, in their rehabilitation medicine department, and I was working with an adviser in a neuro-robotics laboratory in the computer science department. I was on a T32 and she was also very well-funded from NSF and NIH, so she didn’t encourage me to spend time on grant-writing either.

It wasn’t until I started applying for jobs that I began to realize exactly how much trouble I was in. During my phone and in-person interviews, people mentioned that my publications looked great, but that I had no grants.

Fortunately, Boston University hired me despite this. So the whole summer before I was going to start, I had finally gotten the memo that I was in big trouble. I started writing grants like it was my job. (As it turns out, it is indeed part of my job to write grants.)

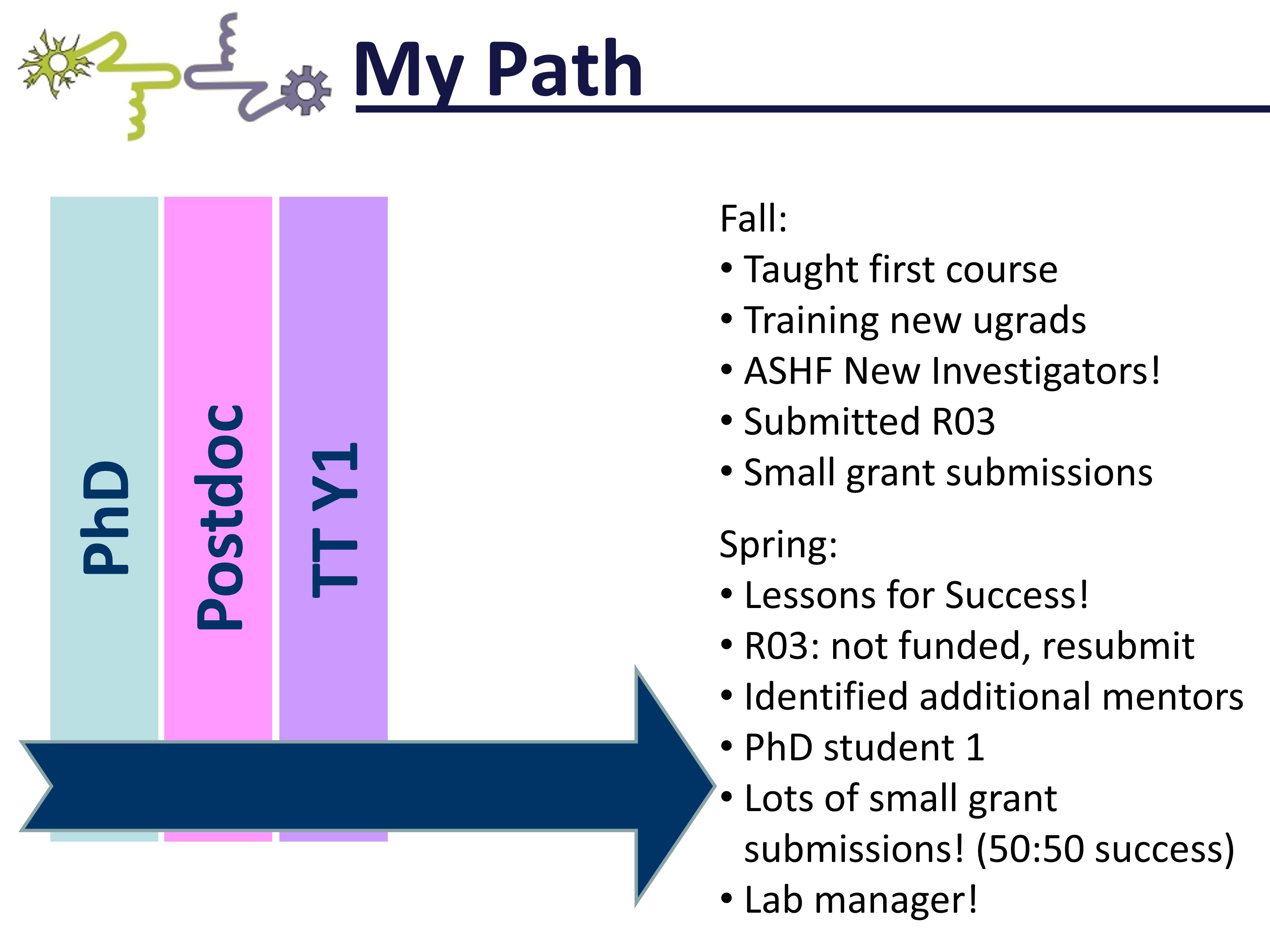

I started my first year on the tenure-track and in the fall I taught my first course. And I’m mentioning that because also, because I was on T32s, I never had to teach. I taught my first course the fall of my first year at BU. For those of you who are yet to negotiate your first year on the tenure-track, many times they will let you negotiate to have a semester off from teaching. A very smart colleague had given me the advice that I should ask for the spring of my first year off instead of the fall. This turned out to be an excellent idea.

So I taught right away, even though I was very inexperienced. It gave me time for everything to arrive in my lab and to train the undergrads who were working with me. This was an important point for me. I was training new undergrads. This was actually really easy for me because I had gotten a lot of experience doing that during my postdoc (even though I wasn’t writing grants!). My postdoc adviser gave me free reign over hiring undergraduates to help me with my projects. This was very useful. When I started my new lab I didn’t have any doctoral students or any other support. However, I had a legion of undergraduate volunteers and because of my experiences as a postdoc I knew how to teach them to help me to build my lab.

I got my ASHFoundation new investigators grant that year, which was awesome. It’s the reason I was allowed to come to Lessons for Success my first year. I also submitted my R03, which was based on work I had done as a doc student and also as a postdoc. A big question for me at the time was “Will they believe I can do this on my own?” One reason I think maybe they did was because the preliminary work wasn’t all completed in collaboration with my doctoral mentors. Some had come through a fantastic new collaboration I had built during my time as a post doc.

I came to Lessons for Success that first year at BU, which was amazing. I think everyone who goes says that, so you should believe it. My R03 was not funded. It had what I thought at the time was an embarrassingly terrible score. It was a 44. I know now, and what a mentor told me at the time was, that a 44 means you are on the right track and you shouldn’t stop trying. At the time, though, a 44 felt like a ‘D’ and it felt humiliating.

So having failed at that R03 attempt and then having it reviewed at Lessons for Success afterward made me realize something. I sat there and I listened to knowledgeable people really rip my R03, even worse than the real reviewers had. This was when I realized that nobody outside of my collaborators had read the grant. It wasn’t that I didn’t try. I had tried. I had sent it to some people, but it isn’t their job to read my grant. You have to beg, borrow, and steal to get knowledgeable people to put their eyes on your grant drafts. The grant applications are long. The margins are half an inch. No one wants to read these for fun.

So, in some ways, I came back from Lessons for Success and I was really depressed. I felt bad at my job and like I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t have a supervisor anymore and I felt like I had wasted all those years of training without learning this vital skill. All those years I could have had my supervisors read my work, but I didn’t know I was supposed to be writing grants. I definitely felt like I was in trouble, so I did something that seemed desperate. I went to my dean at the time and I asked her to hire someone to read my grants. The shocking part was that she actually entertained the idea. She asked me who, and fortunately I had identified someone. He was a research professor at BU. He has gotten something like $30 million in grants over his career because he had been writing to fund himself his whole career. He had some available effort, so she actually hired him to mentor all the junior faculty in our college in grant writing. He reads our grants and gives us critical feedback. It’s awesome.

I also picked up my first PhD student at the end of that first year, which was fantastic. I also put in so many small grant submissions that I felt like I was writing grants pretty much 70 percent of the time. I got some of them and I failed at many of them. Finally, I hired a lab manager, which, if you have the funds to do so, is a really marvelous idea if you do experimental work. I was the one managing calendar and scheduling subjects at the same time as writing all those grants. It was horrible, and I didn’t even realize how reasonable it can be to get someone to help you with those things.

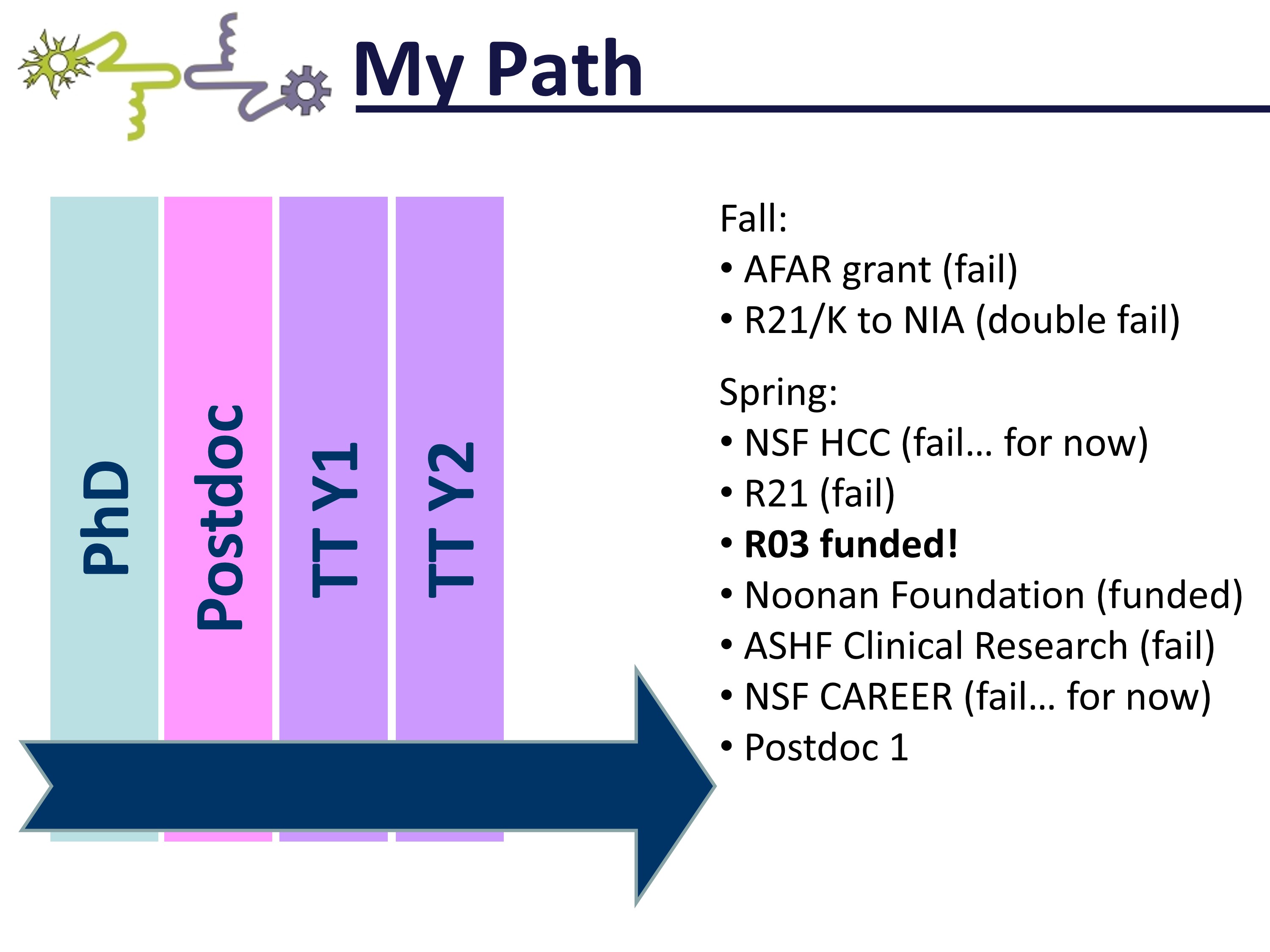

I’ll make a short interlude at the end of that first year on the tenure track. I looked this up: I submitted 13 grants in my first year. I didn’t get very many of those. Writing 13 grants was hard and dealing with so many rejections was hard, too. A colleague in my department told me something that helped. He said that you have to celebrate every single step of the grant. You celebrate when you turn one in, when it gets reviewed (or not), when you get your score, when you think it might be funded – all of them. You should celebrate all of those times, because by the time you actually get the grant, the rollercoaster of these steps may have taken the excitement away. Another thing that helps me with all this rejection is a statically inaccurate mantra I have. Assuming funding rates are 10%, I like to imagine that every time I fail at a grant, I’m 10% closer to success. Of course, statistics don’t work that way, but it definitely helps me. It means that I get to celebrate that step closer instead of mourning the failure.

Coming back to my second year: I had a lot of failures. In that fall I submitted three grants all on the same project. It was a project about aging and neck motor control. I sent it to the American Federation for Aging Research, and they don’t give you reviews so it’s hard to tell how much they hated it, but they didn’t fund it. In the meantime, I found someone at NIH in aging to talk to who thought it would be interesting. I told her about my idea, which was to submit an R21. She encouraged me to think about a K award. Since I’m not eligible for any of the Ks at NIDCD I hadn’t even considered this. So I submitted both grants, a K01 and an R21. Combined that turned out to be the biggest fail ever. Neither were a good idea. However, K awards can be a really great idea in general. Several of my colleagues at BU have them and it has been fantastic for their careers.

Then in the spring of that second year, I failed at an NSF grant. I tried a completely different R21 on a different project, which also failed. But thankfully my revised R03 got funded! That R03 got funded partially because of the amazing eyes that I had on it at Lessons for Success. I also got a small local grant for some of my other work. But, I also failed at an ASHFoundation grant as well as an attempt at an NSF career grant. But I continued to build my lab, adding my first postdoc.

The reason I’m spending so much time telling you about all the different times that I failed is because I’m used to it, but you might not be. I think there are a lot of smart, “Type A” personalities in our field. You may have gotten a lot of A’s. However, I’ve gotten a lot grades there were not A’s. I think this has helped me get used to failing, which makes it easier for me to try things. I would encourage you to not take failure as a personality trait, but as something that has to happen (many times for some of us!)

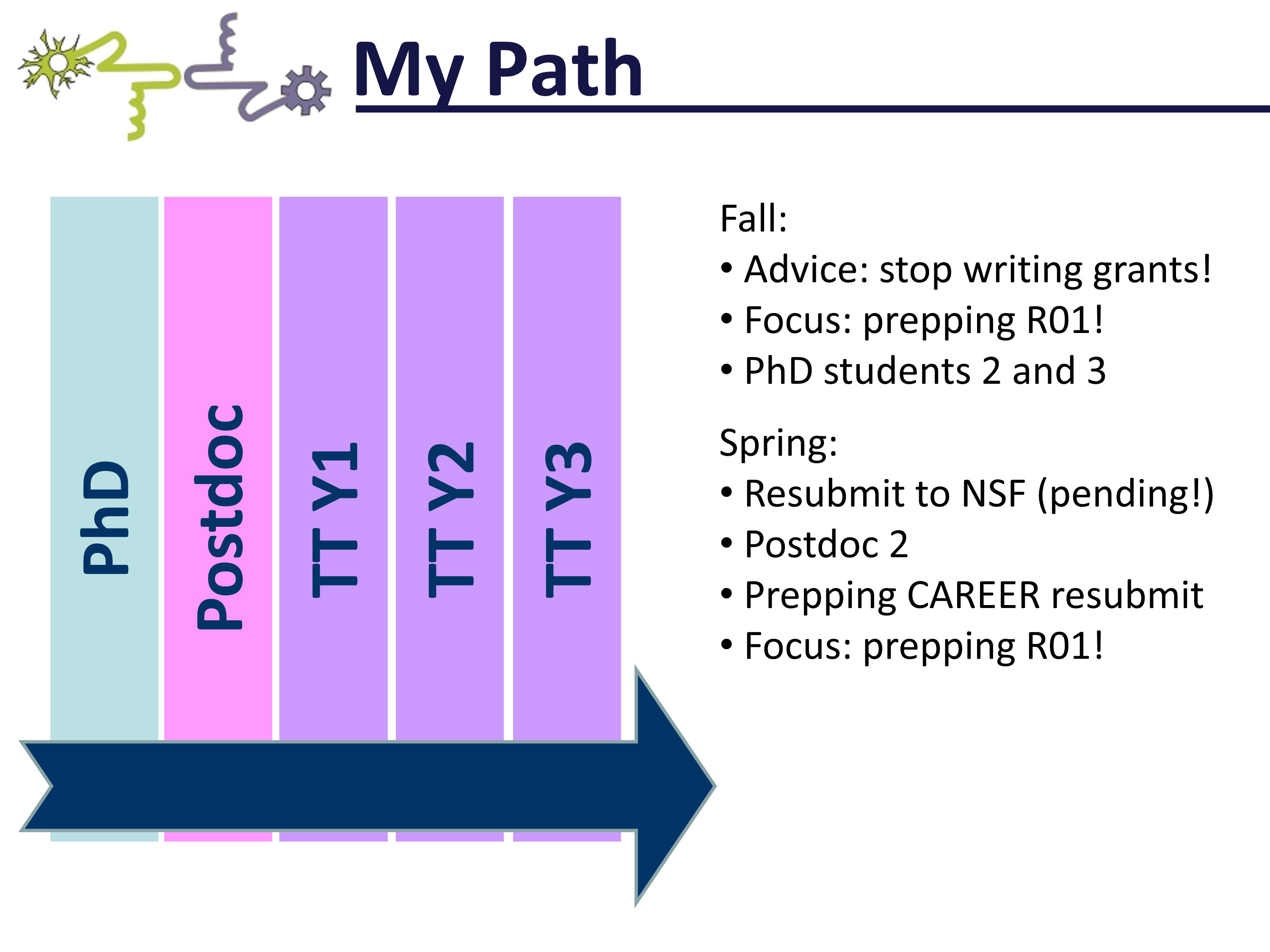

So then in the fall of my third year, I had a really helpful talk with a program officer who told me to stop writing so many grants and especially to stop writing R21’s. I think I needed to write all of those grants those first two years because I needed to get the reviews and practice writing. But now I’m focusing on my currently funded science and long-term preparation for bigger grants. I’m going to keep trying with NSF because I got some really positive feedback, just no funding yet. I’m also going to start prepping an R01 to submit in the next year and a half, I hope. I’ve added two new PhD students, which brings me to three. This has felt like a large number, but also a really nice number. It is a large enough cohort that they can really help one another and build camaraderie. This spring, I have resubmitted one of my NSFs and am prepping my career award resubmit. I also added postdoc number two, and I’m still prepping that R01. That stops the timeline at this point to today.

As I mentioned, I don’t have any answers. I’m just letting you know where I’m coming from and the things I’m trying in case you want to try them too.

Research Strategy

So here are my tips:

- Listen to yourself, but listen to others.

Everyone kept telling me not to do that neck motor control thing. I didn’t listen to any of them. By everybody, I mean, at least six or seven people who I respect a lot. When that many people tell you an idea isn’t smart or interesting, you should just stop. You’re not always right. I was wrong, and I wasted a lot of time and effort on that.

- Go deep, but stay broad.

People have told me that I lack focus. To some degree they are likely correct. On the other hand, I think having multiple lines of projects is smart. There are different agencies to tailor to and just because you think it’s a good idea you could be wrong. Or even if you’re right, someone else may not believe you. I think it helps to have multiple things going on, as long as they are complementary.

- And you should tell everyone what you’re doing.

Because you never know what skills or contacts that they might have that could help you.

Grant Writing

- Early and often.

- Share.

One way that I found that doesn’t really work with senior faculty, but with other junior faculty, is to volunteer to read their drafts. Later when you ask them, they’ll pay it back.

- Sit on a panel as soon as possible.

I’ve been moderately successful at this. If you haven’t already, send your CV immediately to be an early career reviewer for NIH. If you are accepted, they will select from that pool to serve on panels. This hasn’t worked for me yet. However, I have been successful with is getting on NSF panels, which has been amazing. I wish so much I could have done is before I ever bothered to send the first grant there. It’s amazing to see what they’re really looking for and getting the practice in reading the grants. Now that I’ve done that a couple of times I feel a lot more comfortable. NSF is really open to having new people go. I volunteered there and a year went by and nothing happened. Then another assistant professor who I’m friends with mentioned that she had reviewed quite a lot and couldn’t keep up with the requests. She sent my name to her program director and I was asked to review just a week later. So, if you know anybody who reviews for NSF, have them send your name in!

- Don’t take it personally when people don’t want to talk to you.

Program directors are busy people. If you are having a hard time getting them to communicate, don’t take it personally. Keep trying. Eventually you’ll find the right person who can give you the good information.

- Make your work accessible.

I heard this a few different times. I think it’s still relevant for NIH. However, for NSF, having an up-to-date website really matters. Having your papers accessible on your website matters. I heard this from people who were NSF funded, but then when I was on panels I saw how true it was. Sometimes during review, we actually look up the applicant’s website to take a look. NSF panels spend a lot of careful time on the review. Make sure what’s on your website matches what you wrote on the grant.

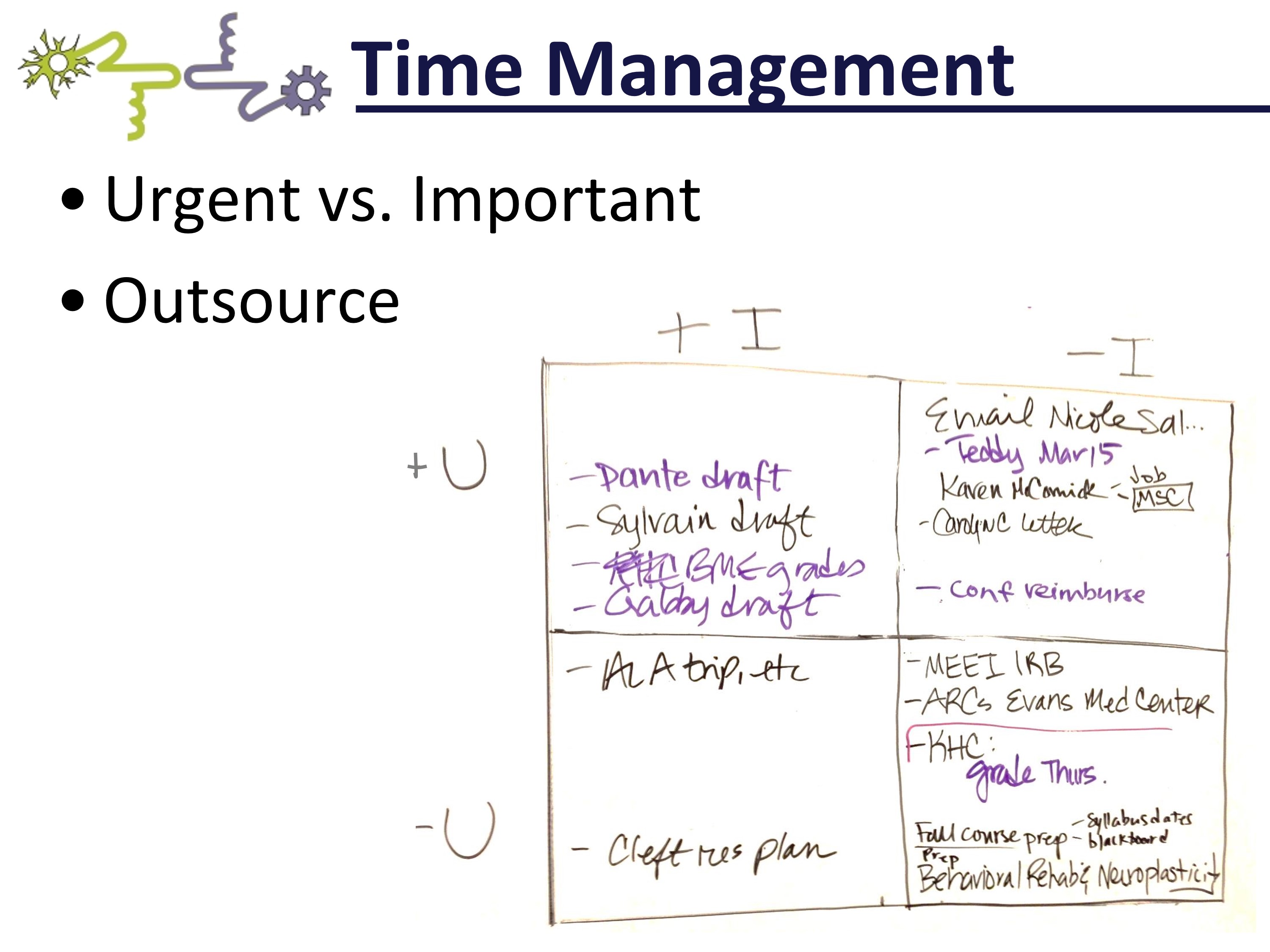

Time Management

Time management is an area that assistant professors think about a lot. This is really random, but it really works for me. I waste an entire wall of my office with a whiteboard. This is a random shot of my urgent-yes/urgent-no, important-yes/important-no. It helps me figure out what I’m allowed to do that day. It helps me not to do the “urgent not-important-at-all things”, or at least to put them off for a little longer. Outsourcing is another important thing to think about. I mentioned I’m actively trying to get graduate students and postdocs, so it’s clear that I think that’s an important step. I think so not just because the education piece is important, but because teaching them once really does save you in the long run – if you get good students.

Getting What You Need

The magic key to getting what you need: Ask for it. I asked for someone to be hired to read my grants and amazingly my dean did it! Then six months later, I asked for endoscopy equipment for my research and for our department’s clinical teaching. It wasn’t something that I had included in my startup request, but I explained why I needed it and why it would be good for the college, and she granted us funds to buy it.

If you have a good reason, you’re strategic, you explain why, and you have a solution, it can be hard for people to say no! I didn’t wait a week in between the two big things I asked for and I also didn’t just go and complain that I had no one to read my grants. Because I was able to point to the action item, I think that helped. I think if you give someone an action item and a good reason, if they have the ability to do it and they want you to succeed, it might work. Of course you can’t be too afraid to fail to ask!

Getting the Most out of Lessons for Success

Getting the most out of your experience here at Lessons for Success is actually the topic I was asked to speak about. I suggest you plan to catch up on sleep later. You know you have to be down in the lobby at 7:30 and they are going to keep you busy all day. There will not be a 3-min break. Then you’re going to have dinner. You’re going to want to network and talk about all of these things with your peers and the amazing mentors who are here. In the back of your mind, you might be thinking about the grading you have to do, the 50 new emails in your inbox, the emergency that might be taking place in your lab – these are all reasons you’ll think you need to get back to your room. Just do that later tonight and don’t think about it. Don’t try to multitask, or you won’t get enough out of the experience. Don’t answer those e-mails, but go back to work on your aims more. Because after you talk to your mentor, you’re going to want to do as much as you can here with them.

For PhD Students

One last thing, which is inspired by a doctoral student at BU who asked me six months ago why he should have to do a postdoc: Here’s why I think you should do a postdoc.

- Because you get more mentors and more sponsors who you can send your aims to later, who might feel some reason to read them for you.

- You can obtain a brand-new network, especially if you move out of the same institution or city.

- You get to practice starting from scratch, with a lot less pressure than a tenure-track job. When you start a new job, it’s not just starting that new job. It’s starting everything new about it. Where’s the copier? How do I do the most mundane things that were easy in my last job? Practicing that skill, of starting over, means you’ll be better at it when you start your tenure track job.

- You’ll get practice with research mentoring. In my case having all those undergrads to mentor as a postdoc was really helpful. Depending on the structure of your postdoctoral lab, you may also get experience mentoring doctoral students as well.

- Getting pilot data and grant writing experience are key benefits to having a postdoc. I sort of failed on that one, but you don’t have to.

- Building your CV so you can get a better tenure-track job is another great reason. The postdoc time will allow you to build your publication record and you’ll be stiff competition for people who didn’t do one.

- Finally, you can use this time to distinguish yourself from your PhD supervisor. I think that’s the big one. If you go right out with your PhD, in some ways, you’re just a more junior version of your PhD mentor. I know I didn’t want to be in direct competition with mine! Imagine writing grants on a very similar area that will get reviewed by the same panel as your mentor’s – which one seems more likely to get funded? I think of the postdoc as the way to get new skills, techniques, and collaborators to add to what you’ve gotten from your PhD mentor, which you can use to really distinguish yourself.