The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

I am Megan Darling White. I’m a postdoctoral trainee at the Waisman Center at the University of WisconsiniMadison. My talk will be geared primarily towards those who are PhD students now, and early postdocs. All you junior faculty out there, stick with me and I promise there will be some tidbits that I learned that will apply to you later on in the talk.

I came to Lessons for Success in 2012. And at the time I had a funded F31 pre-doctoral grant from the NIH. What I did was try to soak in all the things that I could about how to develop my career. When I came, I was really focused on a tenure-track position. I was just starting my dissertation and had one year left. It was right at the time where I would be either going on the job market or looking for postdocs. I wanted to be a tenure-track faculty member, just like I still want to. But when I got here a common theme throughout was how wonderful a postdoc was, and how great that could be for career development

I thought, wait a second, the postdoc wasn’t even on my radar. Maybe I should really think about this. And some of the things I’m sure you’ll hear again today is that a postdoc can be this wonderful time in your life where all you’re doing is research. You don’t have service commitments or teaching commitments. Your commitment is to broadening your research area and developing your programmatic line of research.

And another point that got brought up was that jobs in communication sciences and disorders departments have become very interdisciplinary — so I’m not just competing with communication sciences and disorders applicants. I am now competing with psychology, with engineering, with neuroscience, and in all of those disciplines, postdocs are very common. All of a sudden, I’m thrown into a pool where I might have two or three publications, and I’m really proud of those after my PhD. But it can’t compare to the ten from someone coming out of the engineering department, who’s got the postdoc and the PhD.

Looking for a Postdoc

I talked to my mentor, and we talked a lot about the pros and cons of a postdoc, and when I got home I started thinking really seriously about a postdoc. And here are some of the things I thought about when I was looking for one.

First I just wanted to identify what was my programmatic line of research. What would be the common thread that I wanted to pursue, and really thinking about it in a five to ten year span.

If I was really interested in developing interventions for my career, what did what did that look like for five years, and what did that look like for ten years. And then I identified the skills I needed to be successful in that programmatic line of research. What did I need to learn about, and what did I need to broaden and expand into for me to be able to complete those grants and show the reviewers that yes, I can be successful doing this.

I also thought about matching my research interests with my mentor’s research interests. When you’re thinking about a postdoc you both should bring something to the table. I wanted to bring some skills to a lab so that I could have some expertise in an area that my postdoc mentor maybe was interested in, but didn’t have the expertise in. But then also that my postdoc mentor also expertise that I wanted to learn.

Then I thought about how I was going to be funded. There’s several different methods of funding. There’s a T32, which is an institutional funding grant. An F32 which is an individual grant from the NIH that you and your mentor work with and apply for, and the T32 and F32 are not givens. You have to apply, and you have to be awarded them. And that’s really different than if you go on your mentor’s funded R01, that’s definitely a sure thing. But with that comes different responsibilities. With that, you have to do 20 hours of work on that R01, which is maybe not what your independent project is. You have to think about all those things.

Think about what type of department you’re going to be in. Is the postdoc through an interdisciplinary research center? The postdoc that I have is in an interdisciplinary research center for developmental disabilities. I am not in a communication sciences and disorders department, and the majority of people I interact with are in psychology and human health studies. You have to decide if that’s something that you’re interested in.

And then, will there be a cohort of other postdocs. The postdoc is this kind of different position where you’re not quite a faculty member, but you’re not a student anymore. Are there going to be people in your peer group who are there to give you support while you transition?

Insights from the Job Market

I decided to apply for a postdoc that was a T32. And again, it’s an interdisciplinary research center. They accept two to three postdocs per year. So there was the potential that I would not be awarded this postdoc. So I also went on the job market, because you never know.

The other advice I heard here at Lessons for Success, is if you were to find your dream job, and they were to also want you, you could potentially negotiate for a year delay, go do a postdoc for a year, and then come back to start your faculty position.

So when I was looking on the job market, I applied very selectively. I think I only applied to four universities, but ones that I was very interested in, and they were all R1 research intensive universities.

One of the things that I learned was that everything takes longer than you think it will. When I sat down to do my research statement that every single application asks you for, I thought, “I’ve been talking about my research for long time now. I’ve been doing the same thing. I really love what I do. This’ll be a piece of cake.” And then I looked at a blank screen for three hours. And as Lisa Goffman, who was on my doctoral committee and read my research statement many times can attest, it takes a long time. A long time and a lot of drafts. Budget your time accordingly. Start early.

The best thing I did was to meet with members of the search committee at the ASHA Convention. And this is where you can really learn what that department is looking for. There was a position I applied for, and the position description was really open, it was kind of like, “We’ll take anyone.” But when I met with them at ASHA, they told me they were really looking for an aphasia researcher. Well, I was out of it. I knew right away I was not going to get an interview there, and that was okay with me. I knew that I could just cross that off my list.

It was incredible practice in selling myself. It’s really different than writing a manuscript or doing a conference presentation. Selling your vision of research — it was very difficult to start with, but I think I’m much better at it now after all the practice.

I did get an interview, and it really demystified this dreaded academic interview. I went to lots of workshops. I gave my job talk. But until you go on an interview, you really don’t know how it’s going to go. And I’m so glad that I’ve got that experience under my belt now, and when I go on the job market again, I can say, okay, I have done this before. This isn’t as horrible as I probably think it’s going to be. At least I hope not.

My experience on the job market. One of the universities was looking for someone totally not in my area. One of the universities suspended their search. So I really was a contender for three jobs. I got one of the interviews — so one of three is not so bad. But for all of the jobs, everybody that got those positions either had a postdoc or was already an assistant faculty member at another university. So, I was very thankful then that I got the postdoc. There were a couple weeks in there where I was like, “Ah, I’m never going to have anything.” But I’ve got the postdoc. So, now that I’ve got the postdoc, I’m going to make the most of it.

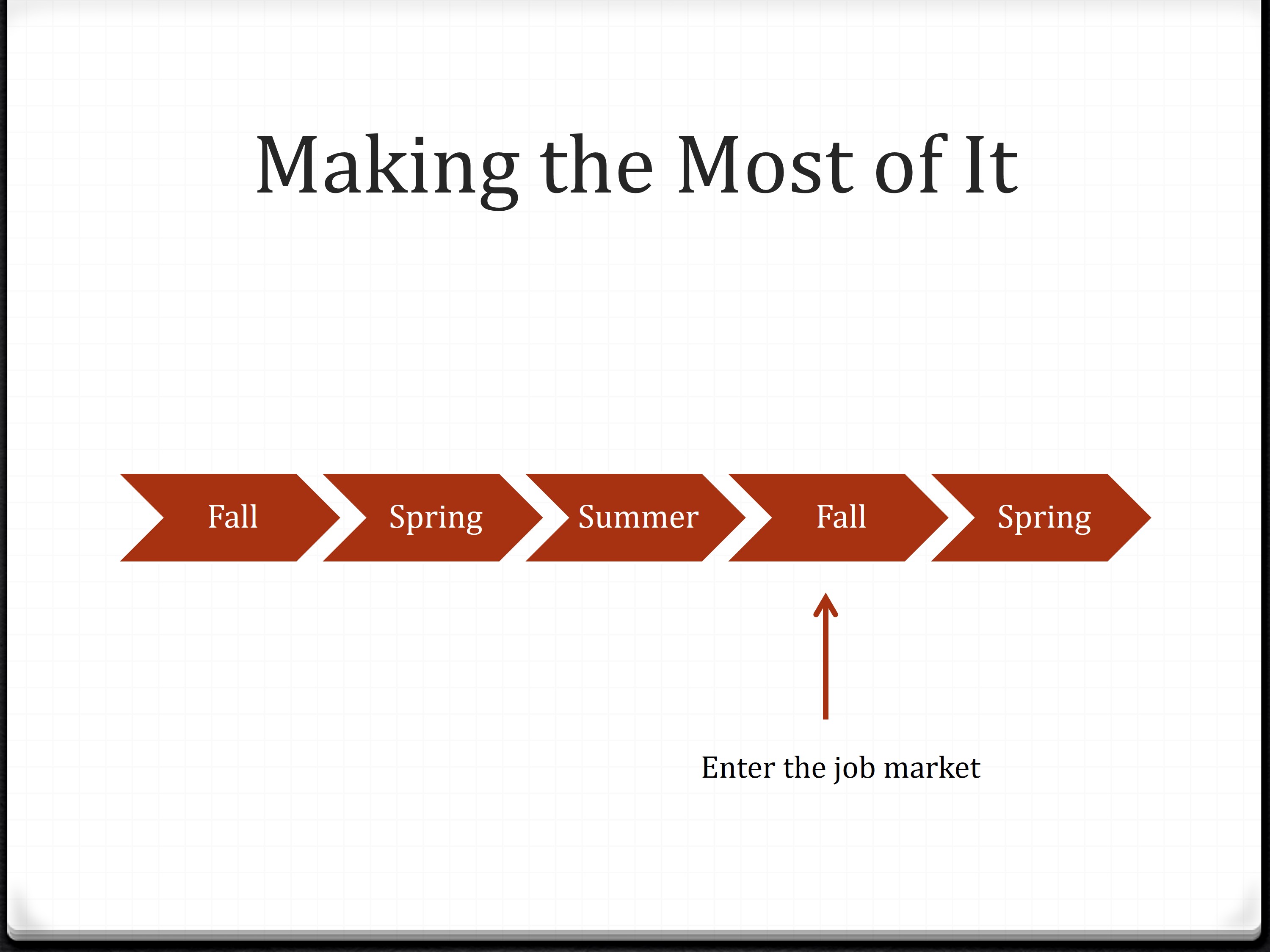

Making the Most of It

My postdoc is for two years. This is what the timeline looks like. It’s a fall, a spring, a summer, then you enter the job market. Looking at this actually makes me stressed out.

You have to remember that when you get somewhere and you’re transitioning, it will take some time. Basically the first arrow is knocked out. The fall is productive in that I made a lot of plans. I read a lot of background information. But the spring is where you start to go. And if you’re going to enter the job market that second fall, you need data and you need it fast.

So develop a plan as soon as possible. What I did is split my plan into three arms. The research development, the professional development, and of course grant development.

For research development, identify the skills that you want to acquire, and then make a plan to acquire them. That was probably the first couple weeks. I sat down with my postdoc mentor and said these are the things that I want to learn from your lab. And then I made a plan for how I was going to do that. And that’s what I spent the entire fall semester on — learning the data collection skills that I needed to learn, reading the background literature on the types of methods she was using that I wasn’t familiar with. And then, of course, choosing my postdoc project. And you need to choose them very carefully.

You always, always, always want to be thinking about your programmatic line of research. There will be things going on in your postdoc lab that you think are really interesting but that do not fit in your programmatic line. So if I went if I went and started looking at maternal response to augmentative and alternative communication. While that is very interesting and I loved hearing about it in our lab meetings, it totally does not fit in my programmatic line. And if I did a project in that, someone would look at my application and think, wow, this person does not know what they want to do, we are not hiring her.

Then you also want to identify projects using your mentor’s existing data set. You need data right away. You need to be able to present something in your job application and then in a job interview. Independent research projects take a while to get off the ground, even if you are planning and starting a plan right away in the fall. Start planning your independent project right away.

What I would do in my dissertation, when I was glazed over and did not want to read anything about Parkinson’s disease anymore, I would pick of the paper on cerebral palsy and it was like a breath of fresh air. I didn’t do it a lot. I just did it occasionally, but it gave me enough information about the area that I was transitioning into to have a really solid research question when I showed up at Wisconsin. And I could start planning an independent project right away.

You want to think about how each project sets you up for the future. So right now I am thinking what data am I going to collect to get the F32, I’ll talk about that in a second, and then how is that F32 going to transition me into an R03. And I’m even thinking about what my R01 is going to be. So all of these things that I am doing will lead into each other, and will lead into hopefully being successful in the big R01.

For professional development, one of the things I didn’t really think about when I did a postdoc, but which I have absolutely loved, is taking the time to transition out of student mode. You have graduated, you are now a colleague. You might be at the very end of the totem pole, but you’re not a student anymore. And this is the time to ask questions of your mentors, of your advisors, and of the people in the department of what academia is really like.

Part of my postdoc program includes a professional department series every Friday. The topics have ranged from academic politics to mentoring to interviewing. And the information I have gotten now as a postdoc, and not a student, is completely different. They don’t want to scare you away from academia when you’re a PhD student, but now I’m getting a much more realistic picture. And I still want to go on to academia, I still want to be a faculty member, but it’s really different. And one of the things that I didn’t think about when I was a graduate student, but I’m thinking about now, is learning how to mentor graduate students. What kind of mentor do I want to be? Do I want to have a really big lab? Do I want to have a small lab? How much time do I want to invest in each one of my students? Learning about mentoring, you really can’t do that until you are out, and it makes you really appreciate what your doctoral mentor and all your doctoral committee advisors went through to get you to where you are.

Attend as many job talks as possible. Go to practice talks by postdocs. Go to any sort of faculty interview. I think before I had graduated, I had seen maybe two job talks. And when I was going to those, I wasn’t thinking, “Oh, you framed that argument really well.” or “That slide looks really nice.” I was thinking, “This research is interesting.” But now when I go to job talks, I’m not necessarily there for the research of the job talk. I’m there to learn how to frame a job talk. What makes a good job talk versus a bad job talk.

Observe different styles of teaching. What I did when I started at the University of Wisconsin, is I identified the people who were teaching the classes that I could potentially teach, and I e-mailed them and asked if I could sit in. And I’m not going there to learn, I already know the material, but sitting in an undergraduate class and watching Gary Weismer talk about motor speech disorders, I learned a lot about how to teach about motor speech disorders. Take those opportunities. This is when you can do that. You’re not going to be able to do that as an assistant professor.

And network. If you are presented with an opportunity to meet someone new, you should take it. And it doesn’t matter what the opportunity looks like. One of the things that the Waisman Center does, is every Friday they have a different person from various universities come to talk about their research, and one of the opportunities postdocs get is to drive them around. I always volunteer. It does not matter if you are from communication sciences and disorders or what university you’re at. I volunteer every single time. Take those opportunities. I literally get five to ten minutes of face time with that person, but you will never know when that will come in handy.

This is one I want to talk about for a bit of time: grant development. I was told it would be a waste of time if you didn’t write a grant in your postdoc. That you have all this time to do research, and you should do it. So these are all the things I learned.

Start early. So I want to submit a grant in August 2014. I started planning in September of 2013. I developed my general grant concept. I outlined what I wanted my specific aims to be. And then I researched what grant mechanism was appropriate. There are a couple open to postdocs, or transitioning from postdoc to an assistant faculty job. So I spoke to former postdocs. I spoke to my program officer. I just got as much information as I possibly could, and ultimately decided to write an F32 to extend my postdoc for another year.

Then I started thinking about how I was going to convince those grant reviewers that I was qualified to complete the proposed project. What I did was make a list of the publications and all the manuscripts that I needed to get out, and I ranked them based on what I was going to do in my grant. I have a manuscript from my dissertation that is about speech intelligibility. Speech intelligibility is going to be in my grant. I need that paper out. But I have another paper about balancing cognition and Parkinson’s. I’m not doing anything like that in my grant. So that’s a little bit lower in priority. While I’m still getting that out, that’s not the first one I’m going to focus on.

You need to think about what research experience you need, and then be shoring up consultants and mentors. Because you may need a little time to convince people to work with you.

And you need pilot data. So create a reasonable timeline for getting pilot data, and factor in the time it takes to get an IRB approved. If you are doing human subjects or animal work, you need that IRB. And it takes a long time. And you’re now navigating a completely new IRB system. You need to get it done.

Get feedback early and often. Ask colleagues outside of your area and give them plenty of time. You don’t want somebody to rip apart your grant the week before it’s going to go in. Give them lots and lots of time. Meet with your university grant specialist to learn about submissions, how early you need to get that grant in. And be flexible.

So, when I got to Wisconsin, I wanted to do an intervention study. I had a great idea. I outlined exactly how I was going to do my methods, and I started writing my specific aims. And then Susan Ellis Weismer read it. She read my specific aims and found several holes in my theoretical background. So I thought, okay, I’m going to rewrite it. I rewrote it, sent it back to her, and she pointed out the exact same holes. Well, what turns out, the holes that she was pointing out were where I actually needed to start. They were holes, not because I wasn’t arguing it, but because the data wasn’t there. I completely scrapped the entire project that I have been working on since September and started over again. Which meant a new IRB, a new specific aims. But, because I started planning so early, I have plenty of time to make an August deadline. So be flexible and be willing to start over again.

Then plan for the waiting period. What are you doing while you wait for the grant to get reviewed? Plan to have it go in a second time. I never think that my grant applications will be accepted the first time. It wasn’t on my F31. I doubt it will be on my F32. So what am I going to do during that waiting period.

Final Thoughts

Just some final thoughts. Be open to the possibilities. If you had told me at the beginning of my master’s degree that I would transition from Parkinson’s disease to kids with cerebral palsy, I would have told you you’re insane. I hated kids, never wanted to work with them. But if I had not been open to the possibility when the opportunity arose, I would have missed a really wonderful career development opportunity.

And then, get a life. For a while in your dissertation, that’s all you can do. You have to graduate, you have to finish. But now, as a postdoc, you can start to do all the things that you like to do again.

Don’t be so hard on yourself. There are lots of things that you learn in this conference about how to be productive. How to structure your time. All of the things that you need to do to be successful. And some of them really worked for me, and some of them don’t. I wish I could write two hours every single day, but that doesn’t work for me. I’m much better with longer amounts of time in shorter bursts. For while, I felt like a failure because I couldn’t write every day for two hours. But you just need to accept the way that you work, and figure out what you can do to be successful.