The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Significance

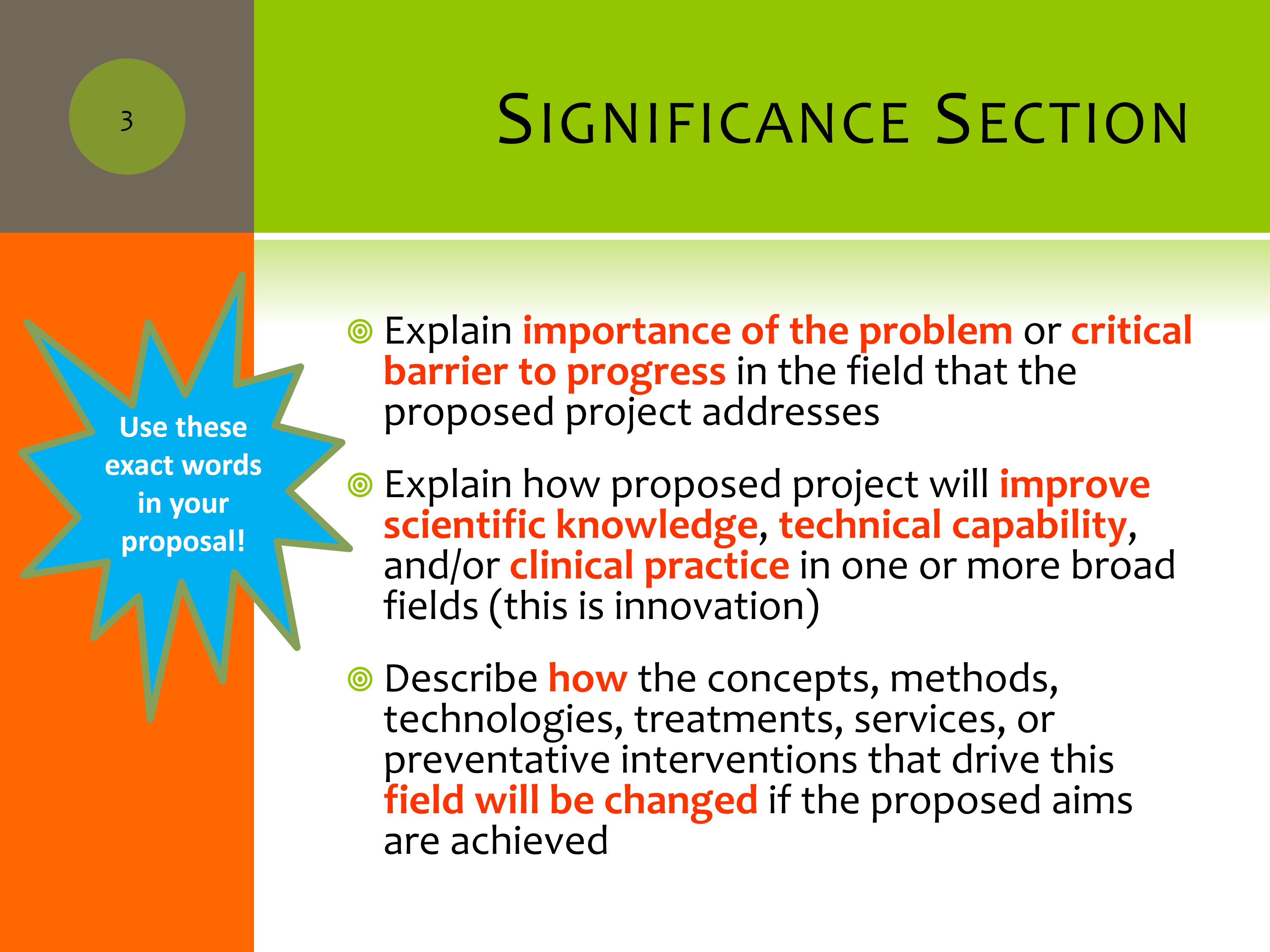

In the Significance Section, I’ve highlighted the key words straight from the instructions on what you should include. What we’re recommending is that you take this exact wording right out of the instructions and use it in your application. That makes it easy for the reviewers to find these critical words that are like little guideposts in your grant application.

You can see the words here. I think someone yesterday said that they keep a list of these things right up by their computer, or right on their desktop, as they are writing to make sure they’re being constantly reminded to include them as they write.

Clarity of Purpose

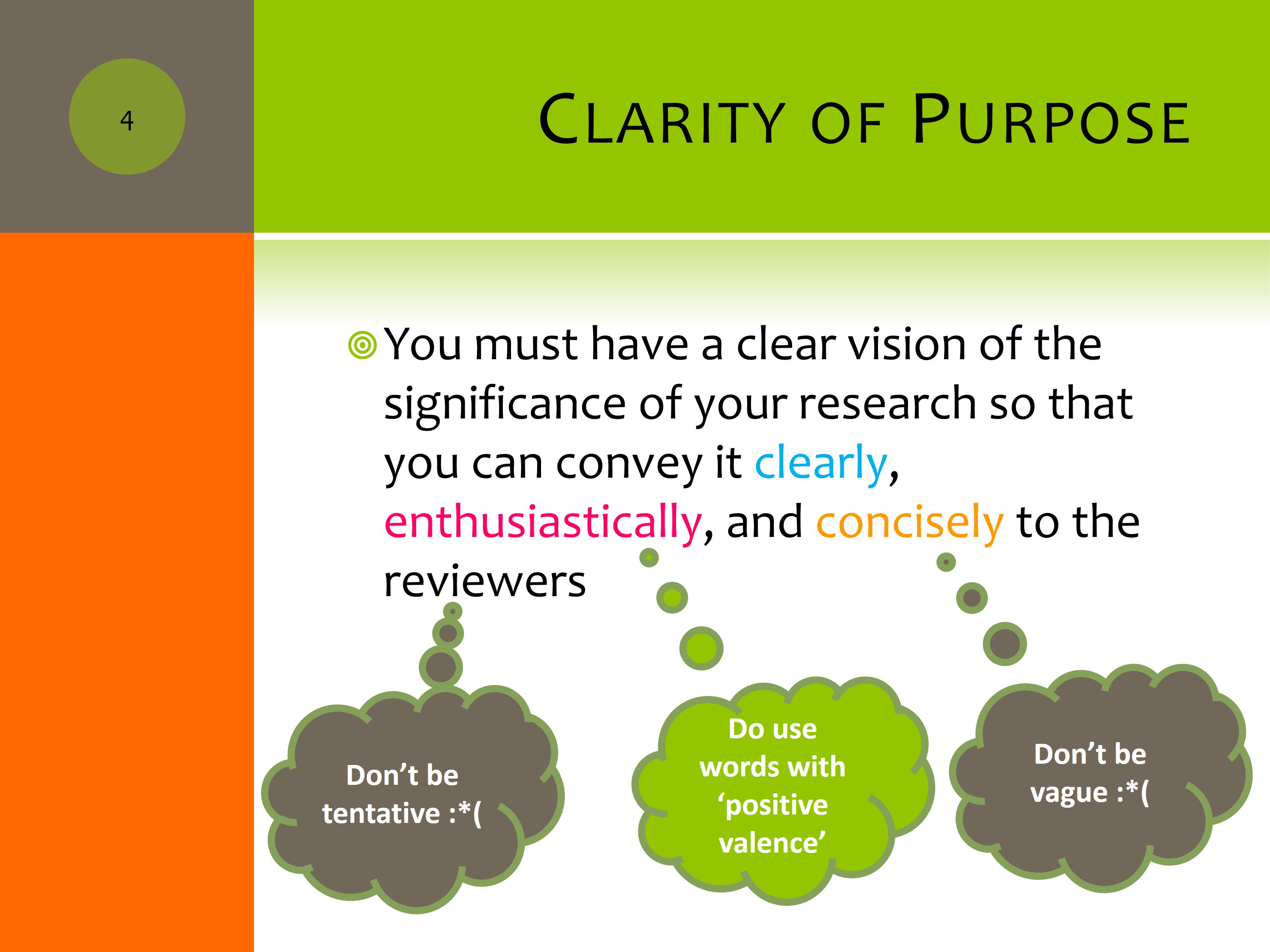

One of the more difficult things to do is to achieve this clarity of purpose. We have broad ideas, we have lots of ideas about what we want to do. For a grant application proposal, you really need to get a laser-focus on what you’re trying to accomplish, and be able to communicate that to the reviewer.

Your wording should convey your purpose clearly, enthusiastically, and concisely. To do that, one of the things I suggest is to use words with positive valence in your application. Words with positive valence evoke happy and positive thoughts as you read them. We’re using priming of positive valence words to help build a positive attitude.

Don’t be tentative. Be proactive and be confident in your grant proposal. We’ll talk about some words that are tentative. And do your best not to be vague.

Words with Positive Valence

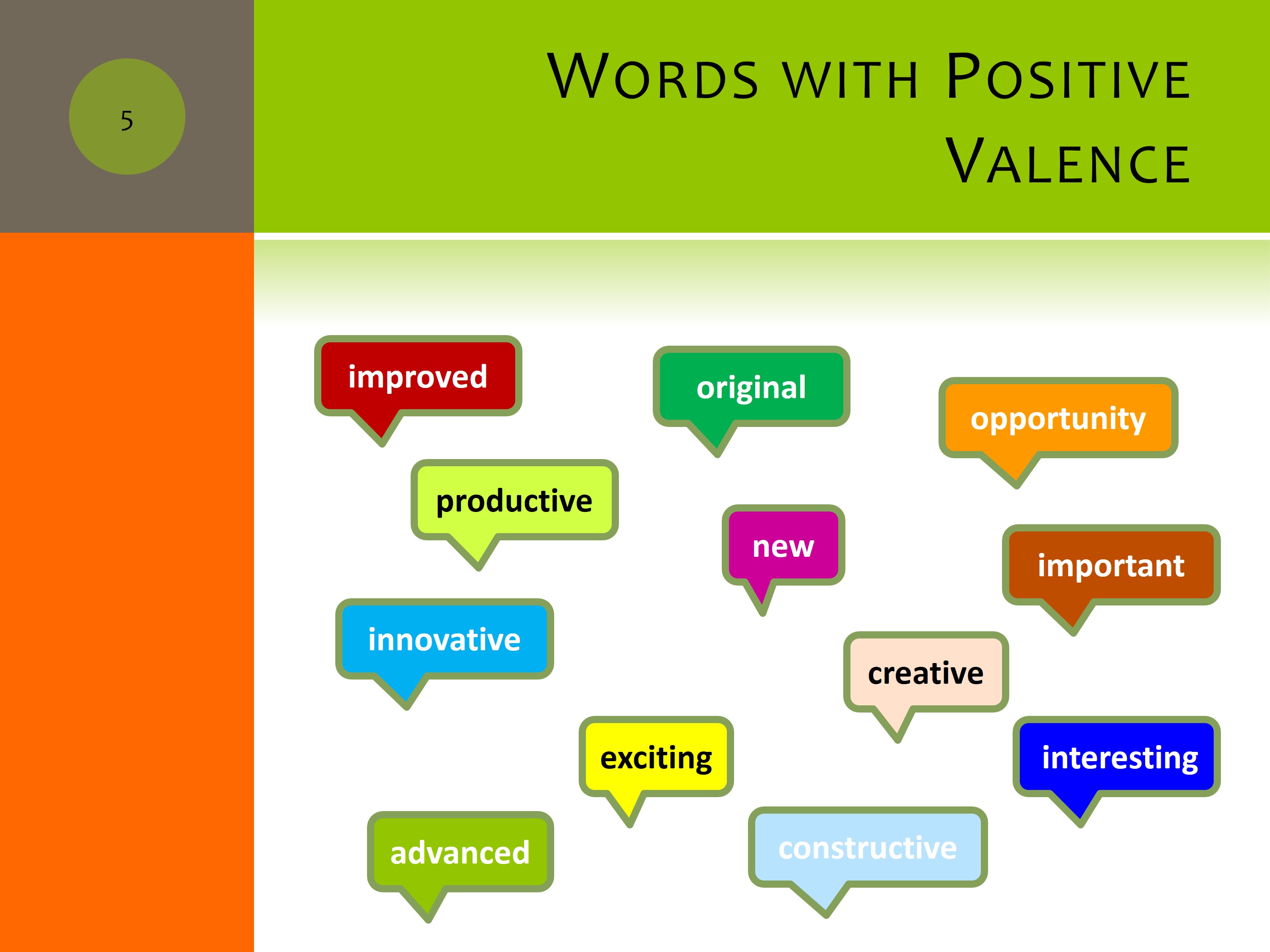

Here are some words with positive valence. Improved, original, opportunity, new, productive, innovative, exciting, creative, interesting, constructive, advanced, important, and you can probably think of a lot of other ones.

You can use these adjectives, but if what you’re proposing is not these things, it’s not going to do you any good. It really does have to be these things. But once you have that in your content and your proposal, this will help create a positive attitude.

Tentative Stance

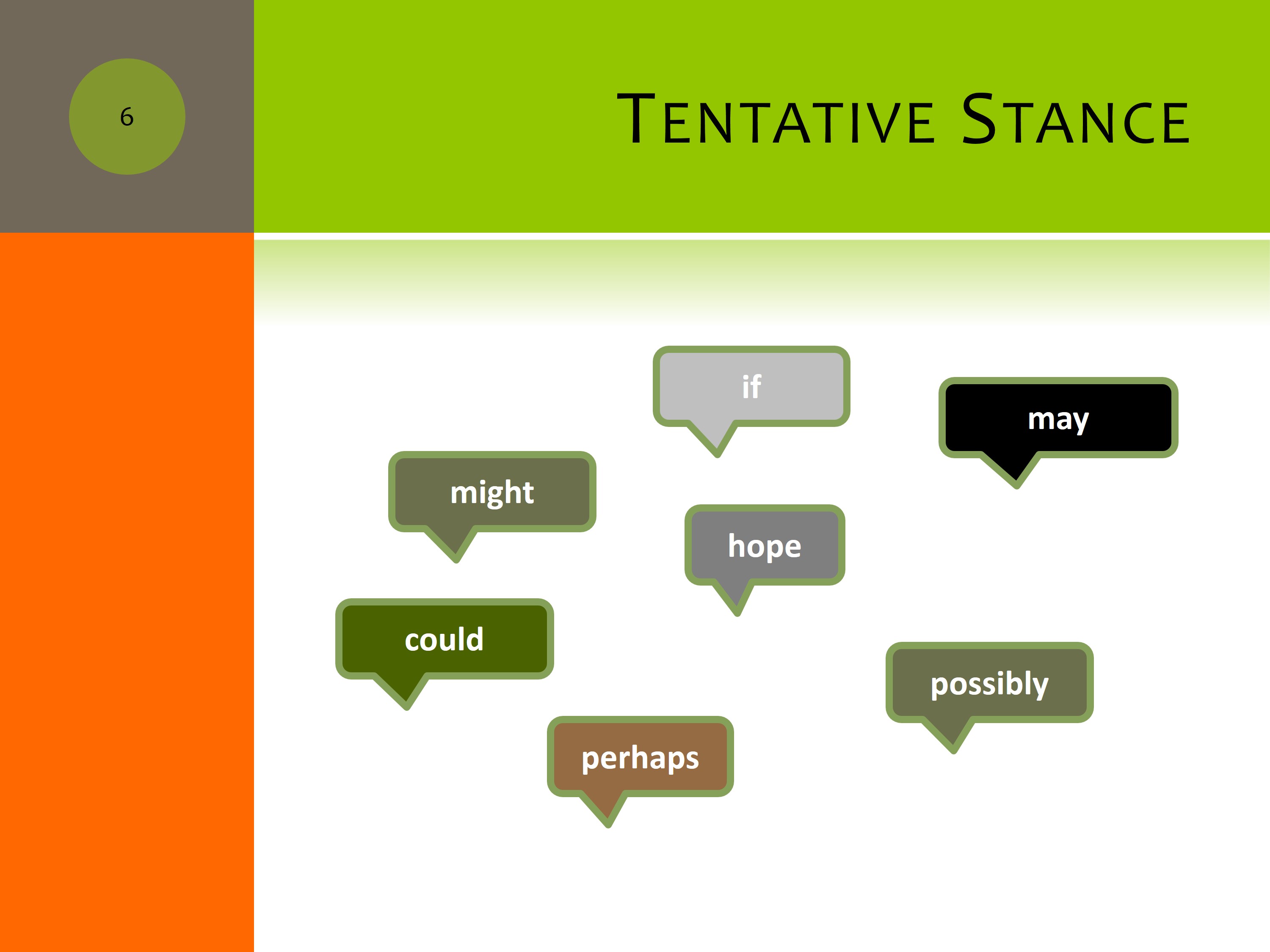

What are some words that convey a tentative stance? If. In science we use “if” statements a lot, but they shouldn’t be the kind of “if” statements that are casting doubt on whether something will turn out the way you think it will. You can use the word if for contingencies and cover both sides of the contingency, that’s important. But what you don’t want to do is raise a problem and not address it.

May — can you think of a replacement word for may?

Hope — we hope this happens. I’ve seen that in a lot of grant applications. Of course we hope it happens, but better not to say it that way.

Might — that’s another one, “it might.” In your grant application you want to plan for every contingency and let your reviewers know that you’ve thought through the different things that can happen and what you’ll do with each one of them. Same with “could.” It could happen, perhaps, possibly.

Do these words evoke a car sales ad to you? Do they make you feel like people can’t really say what this car will do for you, but it might do it, so we’re hedging our bets. You don’t want to hedge your bets in a grant application.

Vague Terminology

The thing and stuff words. Phrases like certain aspects — that’s not too specific. Some properties, a general outcome, the overall conceptualization, improved understanding, observed change, improved outlook. These might be big picture things that can happen, but when you start to use terms that aren’t real specific, it is good for you to think, “Is there something more specific I can say?”

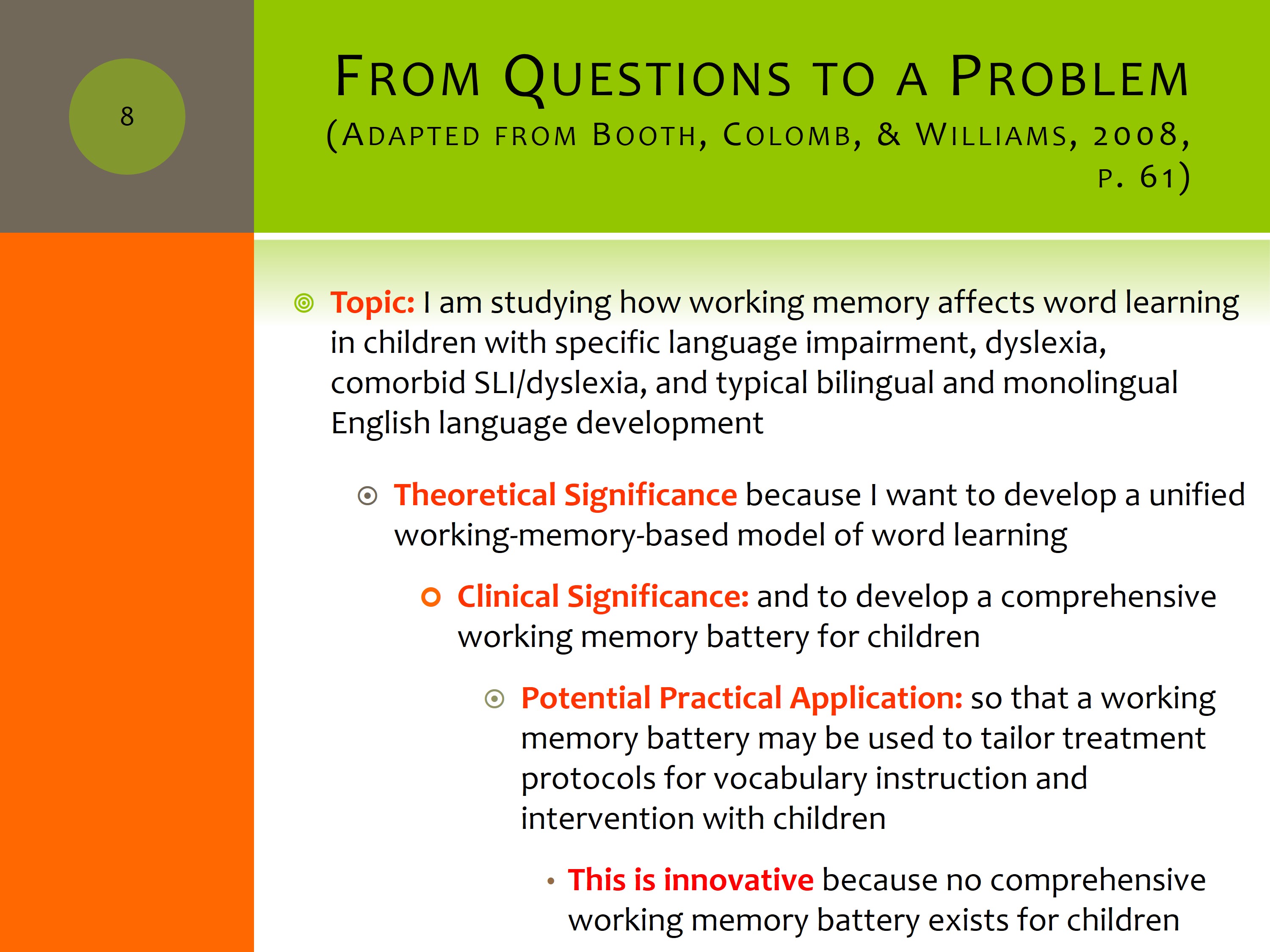

Another recommendation we introduced last year was this book (Booth, Colomb, & Williams, 2008). You can look it up on Amazon if you’d like, but one way to start — or maybe to back up if you’re having trouble with that laser focus — would be to think about something like this. Can I say in a few short sentences what I’m trying to accomplish?

Here’s an example: A real quick description of your topic. Then can you explain what you think the theoretical significance of that would be? What would be the clinical significance? Is there a potential practical application? And why is it innovative?

If you can summarize what you’re trying to do starting with this kind of an organization, chances are you’re going to be able to expand it. As someone was saying yesterday, you really need to be able to present your program of research or grant in a 30-second bite, a 2-minute bite, and so on. This kind of thing will help you do that.

Telling the Story

Integrate Your Story into the Literature Review

Another important thing to do is to think about integrating a story into your grant application. As someone said yesterday, it should read like an action novel.

On one hand, we’re talking about wordsmithing and using good grantsmanship, and you’re getting the wording in there. But on the other hand, you really need a story to unfold. And like any good writer, you’re trying to combine these two things.

What is the story you want to tell about the problem?

What is the problem? Is it an interesting problem? Is it an important problem?

Where does that problem come from? Is it a theoretical problem that we don’t have a theory in a particular area? Or the theory has been stuck at this level of conceptualization for a period of time, and we could move beyond that to suggest new lines of research? Why is it important in your story that you’re telling in the grant?

What are the gaps in knowledge that you’re particularly interested in?

You’re the hero of the story, right? Your solution to the problem is the “Aha. Here comes the main character.” You are the main character and you are solving the problem that you’ve had the opportunity to build credibility for in your background section.

Convey Significance with Context

You want to explain the problem, and what is known about the problem right now in this day and age. It’s important that you are backing this up with current research. That the reviewers know that you understand the breadth of research.

Contextualize what work you have done so far that is helping to build the story. It might be published research. It might be pilot data that you have. It might be part of your training even. It you’ve contributed in any way to this work, you certainly want to highlight that.

You want to propose the next step and tell why what you’re proposing is the next logical step. What do you want to do right now that’s important?

You really need to situate your problem within a theoretical framework, or at least a model to show how you fit in with history, and how you’re part fits in with the longer-playing story.

Example Sentences: Significance

Here are a couple examples to highlight the gap in knowledge or barrier to progress.

In human subjects it is difficult to determine the links among physiology, vocal function measurement, and perceptual quality because it is not possible to systematically manipulate one and observe the effects on the other.

So can you pick out the gap or barrier to progress in this paragraph? The problem is it’s difficult to determine the links among physiology, vocal function measurement, and perceptual quality — and it says not only that it’s a problem, but explains quickly and concisely why it’s a problem.

Then here comes the possible solution to the problem.

Computational and physical modeling are alternative methods for studying the links among physiology, vocal function measures, and perceptual quality.

And it describes it in a very short amount of space.

Here’s a significance statement.

The proposed research is significant because understanding how specific vocal fold asymmetries contribute to voice quality will lead to improved efficiency of evaluation and treatment of voice disorders that involve vibratory asymmetry.

There’s the word “significant” — you might even want to bold it — it explains clearly and concisely why this proposed research is significant. This is the kind of quote a reviewer can lift right out of your grant proposal and put it into the significance section of the review.

Here’s another significance statement from one of our proposals that combines both the theoretical and the clinical significance.

The theoretical and clinical significance accrued across these aims include (1) data-based comparisons of four theoretically-based WM models in children, (2) the development and testing of a new working-memory-based WL model in children, (3) establishing the relationship between WM and WL in monolingual English and bilingual Spanish-English speaking children compared to children with SLI, dyslexia and SLI/dyslexia, (4) a comprehensive description of between- and within-group WL differences in large, carefully selected typical and clinical groups and (5) the refinement of a working-memory-based WL battery for future theoretical and clinical research.

In this proposal, we listed four areas that we felt were contributing both theoretically and clinically to the research base. Then, we also highlighted the population we were going to include, because we thought that was innovative as well.

These studies address important problems in the fields of psychology, language sciences and education, including the need for comprehensive working memory and word learning batteries for children to support valid and reliable assessment and the need to understand deficits underlying poor word learning so that effective treatments can be developed. By completing this research we will advance scientific knowledge in working memory and word learning for monolingual and bilingual children with typical development and children with language impairment and significantly improve the methods for assessing working memory and word learning in school age children.

These studies address important problems — so you’re going to spell out for reviewers exactly what the important problems are and what fields they are likely to impact. That comes right out of the instructions about saying how you’re going to be addressing important problems. Also, we have these keywords, “will advance scientific knowledge” in these ways, and it will “significantly improve the methods” in these ways. If you can’t figure out how it will do it, the reviewers can’t figure out how it will do it. You need to figure it out yourself, ahead of time, and put it in your application.

Innovation

Yesterday we discussed that innovation can be its own section. And some people do make it its own section with a header. But it’s also important to weave innovation and words around innovation throughout your whole application to create an overall positive representation of your work.

You want to use these key words in your application. Seeking to shift current paradigms or clinical practice. Great to put that word in your application. “The proposed work will shift current clinical practice of X by doing Y.” It takes one sentence.

What’s novel about your proposal? There are many different things that could be novel, and you should highlight each of them. The theoretical concept, your approach, your methodologies, the instrumentation or intervention you propose to use. It’s great if you can explain why what you’re proposing has an advantage over what’s currently being done. Sometimes just a refinement in a methodology is an important step forward. Sometimes there is something that has been very successful and well-tested, but you are proposing a very novel application — like the example Holly gave yesterday with a book reading intervention tried with typically developing children, but it’s never been tried with children with language impairment.

As you’re telling your story, weave in about innovation.

Things That Are Innovative

Here are some things that are innovative. A new theory or model. Different application of an existing theory. Bringing in a theory or model from another field that has particular application. Applying a normal theory to a disordered population. New and better experimental methods, better instrumentation, or new approaches to analysis.

Things That Are Not Innovative

Here are some things that are not innovative and all of us have to fight against them.

Using the technique of the day, and thinking everyone will be interested in it because it is the new hot thing to do.

Collecting more data because it would be interesting to know about it. You have to be careful about that word “interesting.” That in and of itself is not innovative.

And the bane of our existence, conducting more research because “very little is known” about this thing. There might be a very good reason very little is known. Maybe nobody cares one bit about it, except for you. Remember you’re going to get a lot of money for this study, so it needs to be something that people care about.

Example Sentences: Innovation

Here are some lines out of different people’s grants with innovation statements. It seeks to “shift current working memory paradigms in children by testing …”, “shift current word learning paradigms by…”, “the proposed methodology goes beyond typical measures of word learning…”, “a novel word learning battery…”, “shift current research and clinical paradigms by studying large, diverse participant groups…”, it’s innovative because “our collaboration itself is innovative.”

What I’d like you to take a minute to do here is see if you can say, “my study is significant because…” and follow that with “my study is innovative because…”

I think a really hard part about this is being concise, and capturing the essence of what you’re doing. If you can’t capture the essence, often you haven’t got the essence yet. This is a good exercise for you — it’s a good exercise for me too.

More on Grantsmanship

A little more on grantsmanship. As I already said, use and highlight the words from the grant package and the scoring guide. You should have the scoring guide that the reviewers are using right there beside you when you write. Tape it up on the wall, put on your computer screen.

Don’t go down side roads. On many of the applications that I read when I review, you see that people have a love of many areas, but often the love of that area doesn’t feed directly into the purpose of the grant. It’s important — don’t let your train go down the dirt road. Stay on the track.

Have a careful, accurate review of the research, with an appropriate scope of research and citations. The reviewers know the literature quite well. If you haven’t done a good job with your literature search, and if you don’t have a command of the literature in the area, it will show.

And use positive valence words.

We talked about figures. Defining your terminology is really important. Don’t use acronyms. But when you’re using a term, make sure you’re defining how you’re using it, because different fields use the same term differently.

We talked about including white space.

The editing. I don’t know about you, but I really need to see it on paper to edit. How many of you that review print out grants? See — there are still four or five people who still print them out. Probably half the people in the room. You need to make sure that, if you’re a better editor on paper, go ahead and print it out and edit.

You should not have any typos or grammatical errors. Zero.

Questions and Discussion

I think we have a couple minutes if you have questions.

Question: How can we avoid “if” statements when we are not certain of the outcomes of our experiments?

I think there is a difference between your hypothesis testing — where you say that if it turns out this way, this is what it will add to our field, and if it turns out this way, it will do this — as opposed to building your story on a series of “ifs,” each one contingent on the other.

One of the things reviewers will always be concerned about is, for example, if the results of specific aim two are contingent on a certain outcome from specific aim one. Because if it doesn’t work, you’ve wasted money. If you write with a lot of if statements, it sets up that expectation. That’s different from hypothesis testing.

Question: My study is not an intervention study, it’s a basic science study. For the significance part, can I imply it is clinically important when it is not directly so for my study? If this is for the future, for long-term clinical importance can I mention this? Or, if it’s not specific, is it better to just not mention it?

My thought is that they are funding the work you are proposing now. That work needs to have impact. If it has impact ten years down the road, I don’t want to pay for that now. That’s my feeling.

Audience Discussion:

- I think what it doesn’t do, is it doesn’t use that space to really boost the feeling about your current work. If it has obvious clinical implications down the road, they’ll be fairly obvious. In my opinion, you would be better off to be really specific about the positive theoretical or scientific benefits of your proposed work right now. Often we can see clinical benefits down the road, but there are so many steps to get there that what we can’t see is the next critical, short-term step. Especially for an R03.

- I’m Dan Sklare from the NIDCD, I would add to what’s been said that you have the advantage, in a fellowship application, or a career award application, of demonstrating your vision five and ten years down the road. I think that showing the impact of a more fundamental study down the road to the field is going to be easier. Because you’re doing that within the context of tracking the vision of your own evolving research career. I think you’ve got a leg up in showing significance and impact.

- Also, don’t walk away with the impression that fundamental or basic science is in itself not innovative. It can be extremely innovative. Of course, its translatability and impact to the field is another issue. I would integrate the two, and I agree with the comments previously made about the importance of showing innovation even in a fellowship proposal.