The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Responsible Conduct Scenarios

In my lab, we play games for valuable prizes. So we’re going to start off with a game for valuable prizes. Here we have it.

Scenario 1

Scenario 1. You are collecting data at a preschool, and the school director has been really helpful in facilitating your research. She’s provided space, distributed flyers and personally encouraged parents to participate. One day, the director says to you, “I see Sammy did your project. I’m glad he did because I’m a little worried about him. How did he do?”

What do you do?

Audience Answer:

- I’m thinking if the parents gave permission and requested the information, they could be given the information and it could be shared that way.

You have the correct answer. Again, what we do in my lab is that I have a protocol. You may not share information with a third party without the written permission of the subject or the parent.

Scenario 2

Scenario 2. You are testing a college student who signed up for our study. He reports that he does not have a prior diagnosis involving language or learning difficulties. According to the standardized tests you gave for the study, the student shows clear signs of a learning disability. In addition, he has told you about his plans to apply for grad school. If he found out about his learning disability, he could get help through the University’s disability resource center and would likely have a better chance of getting into grad school.

Should you tell him that he has a learning disability?

Audience Answer:

- This one I learned from my mentor: We are doing research. We are not diagnosing. We have no right to give them any diagnosis.

Absolutely. In fact, there has been a lawsuit over this very issue. Somebody was given a diagnosis they did not ask for and suffered psychological harm from that experience. So that would be a big no-no. If you feel like someone may suffer harm from not knowing a diagnosis, in my lab (and these are undergraduates doing the testing) their next step is to come to me.

Scenario 3

Scenario 3. This one actually did happen today, and it’s happened before. A college student has signed up to participate in your study because he will receive credit in Psych 101 for volunteering as a research subject. The faculty member who oversees the Psych 101 study participation system has been complaining about labs not providing enough research study opportunities for all the students that want them. When the student arrives, you read his information sheet and you see that he is not yet eighteen years of age.

What should you do?

Audience Answer:

- Assuming that your inclusion criteria for your study are that your participants must be eighteen years old, then you do not run that participant.

- I just want to add, that if you’re teaching an undergraduate class, make sure you give alternate credit because you can get into a lot of hot water if someone says, well I’m not eligible and I can’t get the extra credit.

That would be correct. We actually have a whole protocol about when that happens, when the participant is underage and they still want the class credit. The important thing is that your lab knows this is an issue, and they know what to do in this situation.

This is actually an exercise that we do at the very beginning of our academic year. We have a lab party that assures people will show up, and we go through about a dozen of these scenarios that have to do with research in my lab.

Responsible Conduct in Context

Establishing a Responsible Environment

This is about establishing a lab environment for the responsible conduct of research in terms of research participants. And we need to cover this because the integrity of your lab has to do with the environment that you set. It doesn’t happen by accident. You need to put a little bit of thought into this.

Infamous Human Subject Breaches

Everybody has been through these in the CITI training or whatever else your institution requires. We’ve all heard about the egregious things that have happened over history, but the reality is that you are not likely to infect kids with Down Syndrome with Hepatitis C. You’re not likely to not treat men with syphilis over a twenty year period. These are not IRB/human subjects protection issues that are really relevant to your daily life.

Actual Issues That Do Occur

Instead, these are the things that come up. And you may not be present when they happen. So you need to make sure the people in your lab know how to translate these vague principles that are being illustrated by the Nazi war experiments into things that actually happen when you’ve got a four-year-old in front of you. That’s the point.

Real-Life Vulnerabilities

You need to give some thought about what kinds of things are likely to happen and the potential IRB and responsible conduct situations that they relate to. And make sure that people know how to responsibly handle them, because they come up on-the-fly.

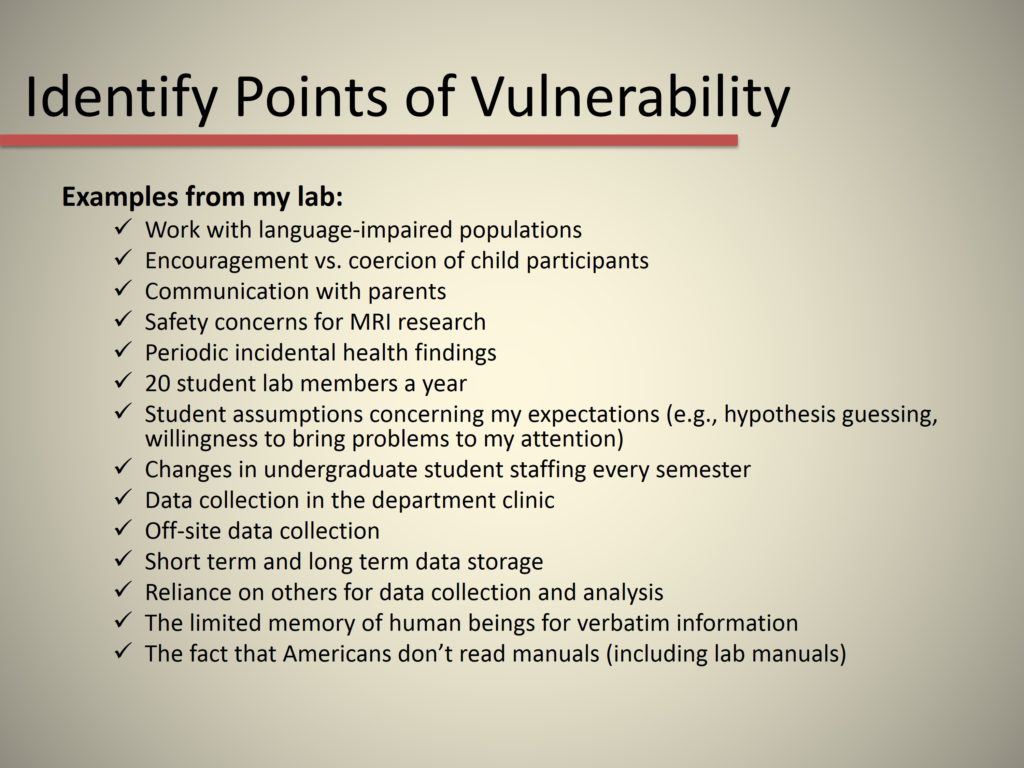

I recommend that you really think about what the points of vulnerability are in your own lab. Maybe this is a lab that is really your own lab or maybe it’s a lab where you are a student. But think about it: Where are the points of vulnerability? Where might responsible conduct of research problems arise? And what might you do to proactively work with them?

Identify Points of Vulnerability

So these are examples that come from my lab, and I’ll just highlight a couple of them. We talked earlier about periodic incidental findings. I had one of those come up two days ago. The fact that we do off-site data collection makes us vulnerable to breaches of confidentiality (more so than if the data was collected in our own lab). The fact that human beings have a limited memory for verbatim information, so even if I tell people things verbatim, that is going to drift away out of their memory. And the fact that we’re Americans, and we do not read manuals, including lab manuals. So, how am I going to make sure that people really do know what these principles are, given that no one has opened a lab manual in the history of my lab?

Discussion

What are YOU doing to reduce your vulnerability?

What we want to do is think about what the potential vulnerabilities are in the lab you’re in right now, and what you might do to reduce your own vulnerability to violations of IRB and responsible conduct of research issues.

Audience Comments:

- One of the things that came up was people who have appointments at multiple institutions. You have to be careful about IRB coverage for protocols at both institutions, transferring protected health information, and making sure that all is kosher between the institutions.

- The other has to do with training people, such as laboratory managers, in IRB-related issues, as far as: What’s an adverse event? Was it really an adverse event? Was it really related to the research study that was being conducted? And trying to balance that communication with those individuals.

- We discussed a vulnerability that is an ethical issue as well, more so than an IRB violation. We talked about if you are a clinician, and you have a patient you would like to recruit as a subject for a study, do you as the clinician who is working on that study recruit? It depends on if you have someone out there who’s available to consent for the IRB, but also, we talked about ethically how we usually defer from this.The point here is that, for your lab, you need for people who might be in the position to get in trouble with that to understand what their potential role might be and what the limits of that role is.

- We talked about a study that involved collecting data on the MMSE (Mini-Mental State Exam) and finding low scores. You don’t share that information with the participants.

- The problem is that a lot of times the PI knows what you are supposed to do, and the lab manager knows what you’re supposed to do, but the person on the front line – that’s where your point of vulnerability is. And you have to manage that point, the one on the front line. Because what’s to stop them from saying, “Oh, you’re really low.” You know you would never do it. I know I’d never do it. But the point is, I have to know that my front line people would never do it.

- We talked about several things. One of them is getting consent in people who have language comprehension difficulties and/or dementia. Anything that might get in the way of their comprehending the materials you’re presenting to them. And we talked about a number of possible ways to deal with this. One of them is to use a formal measure to assess whether they are competent to consent. Another is to have a place for a proxy person to sign and always have another person with them to provide consent in addition to them. You have to have simplified language in your consent form, the IRB usually asks for that.

- We talked about a couple of issues in terms of recruiting your own patients, and how you can distance yourself in research projects from that conflict of the dual role that you might have as researcher and clinician. In one case, it required a doctoral student hiring a research assistant because the doctoral student was the director of the school for autism. And of course she wanted to do her dissertation with children who have ASD, and so she couldn’t really know who participated or not. So the data were collected by somebody else, and she got completely de-identified data. That’s how we got it past the IRB. And more recently there was a similar project, where we were looking at first- and second-generation speakers of Spanish and some of the subjects who will be recruited are in classes where the doctoral students in linguistics who were involved in the project are adjuncts. It is the same kind of thing: You appoint a recruiter, and the instructor leaves the room, and then the data are de-identified so that the person who’s the adjunct can deal with data and not know who’s participated.

- We talked about an issue of what can happen when a long-term employee has been around who might be less cautious about leaving personal information about participants out. And about how that could be a little bit awkward, or a lot awkward, for new people who come into a lab to try to navigate ways to promote change. One suggestion was to make sure that people are doing their research training annually, and we also talked about the idea of when that might not be an issue. If it’s not actually in a public area, then it might not be as big of a deal as one might think.Along those lines we collect some of our data in our university clinic. You know what? The clinical faculty wander through there all the time, so we have to think about how we keep the research privacy in a space where other people who aren’t research-trained in research integrity and responsible conduct are coming through for legitimate reasons.

I think what we’ve discovered here is that it is a lot easier to identify the points of vulnerability than to come up with a strategy. But if all you’ve done is identified the points of vulnerability, you haven’t really done anything to manage your risk. And so you really need to turn to the idea of what are you doing to be proactive.

So think about these things proactively, and have a plan.