The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Holly Storkel:

We’re picking up basically where the review leaves off. So we’ve walked through all of the sections, how to write each one of them. You’ve seen a little bit about how grants are reviewed and so forth. And so, now we’re back to the point where you have gotten that review back.

And so, the first thing you’re going to see is your overall impact score. As we mentioned before, this will be available to you on Commons fairly quickly after the grants are reviewed. If your grant was not discussed, you’ll just see little asterisks or something in your score. So if you don’t see a number that tells you that your grant was not discussed, it was in the lower half of applications.

William Yost:

When you look at the individual scores you get on the criteria, significance and stuff, you’ll see a number like one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine. And then when you see your impact score, it’s 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, or something like that. That’s because all the members of the study section vote in one, two, three, four, fives. And then that average is taken and multiplied times ten. So it can go between 10 and 90.

Holly Storkel:

So then you see there, you’re going to get a number between 10 and 90 if you were scored. And here’s just a little bit of an idea of how you might interpret that number, that generally 10 to 30 might be fundable on that round, but you should talk to your program officers about that. You know, what’s fundable changes from round to round and will vary by mechanism and so on.

If you get a score between 40 and 60, that’s probably not going to be fundable. But again, talk to your program officer to get their impression. But that is some encouragement to you that there were things that they liked. It was discussed. That tells you it was in the top half and so you should feel good about that. And this is now where you might be moving towards a resubmission.

And then if you have scores below that, that’s perhaps less encouraging. And so, you really will need to see what the content of the reviews are like to decide if it’s worth your while to go through with a resubmission, but it could be that you’re going to need to do some considerable rethinking and re-crafting, re-conceptualizing of your grant, given that negativity, and potentially the same for the applications that are streamlined. But again, it all just depends on what those comments are.

For many grants, you’ll also get a percentile score. This is typically done mostly with the R01s, but there might be a few other mechanisms that also get percentile scores, depending on what institute you’re in and so forth. So you might see a percentile score.

William Yost:

And just so you know why and what that is, the why is that different study sections wind up sort of being calibrated differently. So if you happen to have a proposal that was in one study section and got lots of 20s and 30s, that quality may be no different than a study section that has a stricter kind of culture of 40s and 50s. So to normalize that, that’s basically what this is, is a normalization process. It turns it into a percentile across the study sections with a sort of a three-year running average. So it takes into account some history of what those study sections did. And that does set the pay line for R01s in NIDCD.

Holly Storkel:

And then eventually, you’ll get a summary statement. That takes several weeks before that appears on Commons. So then you should talk to your program officer. Again, they’re going to be the ones who can help you interpret your score and figure out what’s going to happen next. And so, we’re going to consider sort of two different scenarios. One is the good score, where it’s going to move on immediately to Council and you think you have a good shot at getting funded, and the other is a poor score or not discussed, and this is where you’re going to immediately move into resubmission mode.

Advisory Council

William Yost:

Let me just jump in here and talk about council for a second. You’ve heard it a lot, but we haven’t really talked a lot about it. For early stage investigators and new investigators, it does have a little bit more of a prominent role in what might happen at this stage than other kinds of investigators.

By law, every institute NIH has to have an Advisory Council. The Advisory Council’s primary role is to make the recommendation to the director of the institute of what should be funded. Does Council read every proposal? Absolutely not. Does Council read every summary statement? Absolutely not, okay. We do things– I used to be on a Council. I won’t say we anymore. Council does lots of things in blocks, it relies heavily on staff. But at the end of the day, every single proposal has passed through a Council vote as to whether or not the decision that has been decided upon, funding, not funding, et cetera, meets their approval.

The key issue is at NIDCD, 10% of the budget is set aside for Council discretion. And that’s the highest percentage in NIH. There’re others that do 10%, but some institutes do less than that. So Council itself has 10% of the money to fund things. And Council funds things basically in two ways. Staff suggests to Council proposals that are in that 40 to 60 or maybe 30 to 60 range, depending on the pay line, the mechanism, et cetera, whether they believe for certain reasons a grant that wasn’t funded should be put into that 10% that we are going to consider. And then that is assigned to a Council member or two or maybe three to evaluate. So the staff might say that I think Holly’s proposal should be considered, and we look at it and make a recommendation to the entire Council and then the entire council votes. Or a Council member can look at the summary statements and decide based on the summary statements for usually reasons of discrepancies and what they see in the summary statements. They may see lots of twos and threes and a couple nines and they look at the rationales for the nines and they don’t quite believe that’s substantial enough to have kept it out of funding and then they make a case. And there could be lots of cases. These could be RFPs that were sent out that the NIDCD has decided there’s a target area that they want to support and they’ve had one. And this is in that area but didn’t get funded. We’re supposed to support those so we might elect to argue that it should be moved up.

For ESI and NIs, new investigators, most likely, but not necessarily 100%, if you are discussed, you will be asked to submit a letter to Council. And that letter can be more than the one page you have for your revision, which we’re going to talk about in a minute, to talk about your grant, talk about the review, talk about the summary statement. Those letters go to staff and then staff assigns them to one or two, usually two, Council members. Council members are to read them and if they think that helps them in making decisions about whether or not they want to pull that grant into that 10%, they will use that in their presentation to the general Council as to why they think that proposal should be done. And that is for ESI and NI investigators the primary tool Council members use. You know, I got a letter. They got this new pilot data. They’ve done this. They’ve done that. And that could be extremely persuasive to move that into the 10%.

One final thing and I’ll shut up. Most of the time, but not all of the time, the number of proposals that council recommends moved into this 10% funding is more than the 10%. And the discussion that takes place guides staff into how to make a decision to disperse the funding to those people who are in the 10%, so that they stay within the 10%. That is to say that many times, you might find yourself talking to your program officer with sort of good news, maybe not so good news. Good news, we’re going to fund you, but we’re only going to fund you for three years. Or we’re going to fund you, but we’re only going to fund you at 80% of your budget. Now staff will avoid doing that to the extent possible for EIS and NI within NIDCD. They will try to fund the full time and amount, but it just depends on the cycle and how many things were in the 10% pool whether or not you might wind up getting the good news, not so good news message. You probably don’t care as long as you just get the good news message, but it might be an issue if you have research that needs a certain amount of a budget. All right, I’m done.

Letter to Advisory Council

Holly Storkel:

That’s what we’re going into next is the option of writing a letter to Advisory Council. And this will be clear whether you are invited to do this. You’ll get an official thing that asks you to write a letter and you should also talk to your program officer for their advice before starting that letter about whatever the current advice is. I think right now or at least when I last did this, she said we could write two pages in the letter. No more than two pages for the letter. And another thing to be aware of too, it’s good to look at who’s on Advisory Council even before you submit your grant. So we’ve talked a lot about finding who’s on your study section, but you might also just want to look ahead to Advisory Council, too. And you know, when I looked at it, when I had to write a letter, there were not hardly any child language people on there. So it’s good to know that, and it’s good to see too that there’s people from the community, there’s practitioners on there. They’re not just scientists that are on that panel. So you want to look at that and be thinking about that, particularly for your abstract. All Council sees is your abstract and your summary statement. They don’t see your grant and they are going to maybe see this letter that you’re going to write as well and that’s it. So make sure that you are writing it for Bill, who’s an audiologist, even if you’re a child language person.

William Yost:

Let me just amplify that a little bit. Remember now, this is the Council of NIDCD. This is not like AUD or LOC or something like that. This is speech, hearing, language, balance, taste, smell, and anything that’s close to that. And it’s not just scientists. Someone from ASHA has been on Council many, many times. People from industry. Parents, people with disabilities, hearing loss, et cetera. A whole variety of lay non-science people are on. They’re very smart, very educated, and very knowledgeable. Maybe even more so than some of us who are sitting there as scientists about what’s going on in the field and what the needs are. So if I make a plea to them to include a grant in the 10%, I’m not going to use jargon. I’m going to take the most general overview I can. And where do I get that information if it’s not exactly what I know inside and out and, because it very often isn’t, because I’m the only hearing guy or at least the only perceptual hearing guy on the Council. There may be two other people who do hearing. Where am I going to get the ammunition to present it? From your letter or from your abstract. That’s where I get the ammunition that I can use to convince Council members to go along with my request.

Audience Comment:

So I have a question for you, Bill. So over the past few days, we’ve looked at how study section works and we’ve sampled level of discussion that occurs. Can you give us a sense of the level discussion that occurs for an application that you want to advocate for?

William Yost:

The level of discussion at Council at this time can be basically none. To maybe 15 minutes, maybe 15 minutes.

Holly Storkel:

So what goes into this letter? I think we’ve said a lot of this about if you’re kind of on the bubble and you’re asked to write a letter, this letter is going to be very important. And the first part– I’m going to show you an example letter. The first part of your letter is going to sort of set the stage for your advocacy for your application, and then the remaining part is going to look a lot like the introduction to resubmission, where you’re responding to specific reviews. So I’m just going to show you a portion of the letter that’s a little bit different and then everything we talk about in terms of what goes into the response to reviews or the introduction to resubmission would be information that you would include for Council as well for this letter.

In writing this letter, it’s good to familiarize yourself, which you probably should’ve done before you wrote the grant anyway, with the NIDCD strategic plan. So what you’re asking council to do is really to designate your areas or your grant as high program priority so that it can go into this 10% pool. Well, if you want to be high program priority, you better know what the priorities are so that you can argue for that.

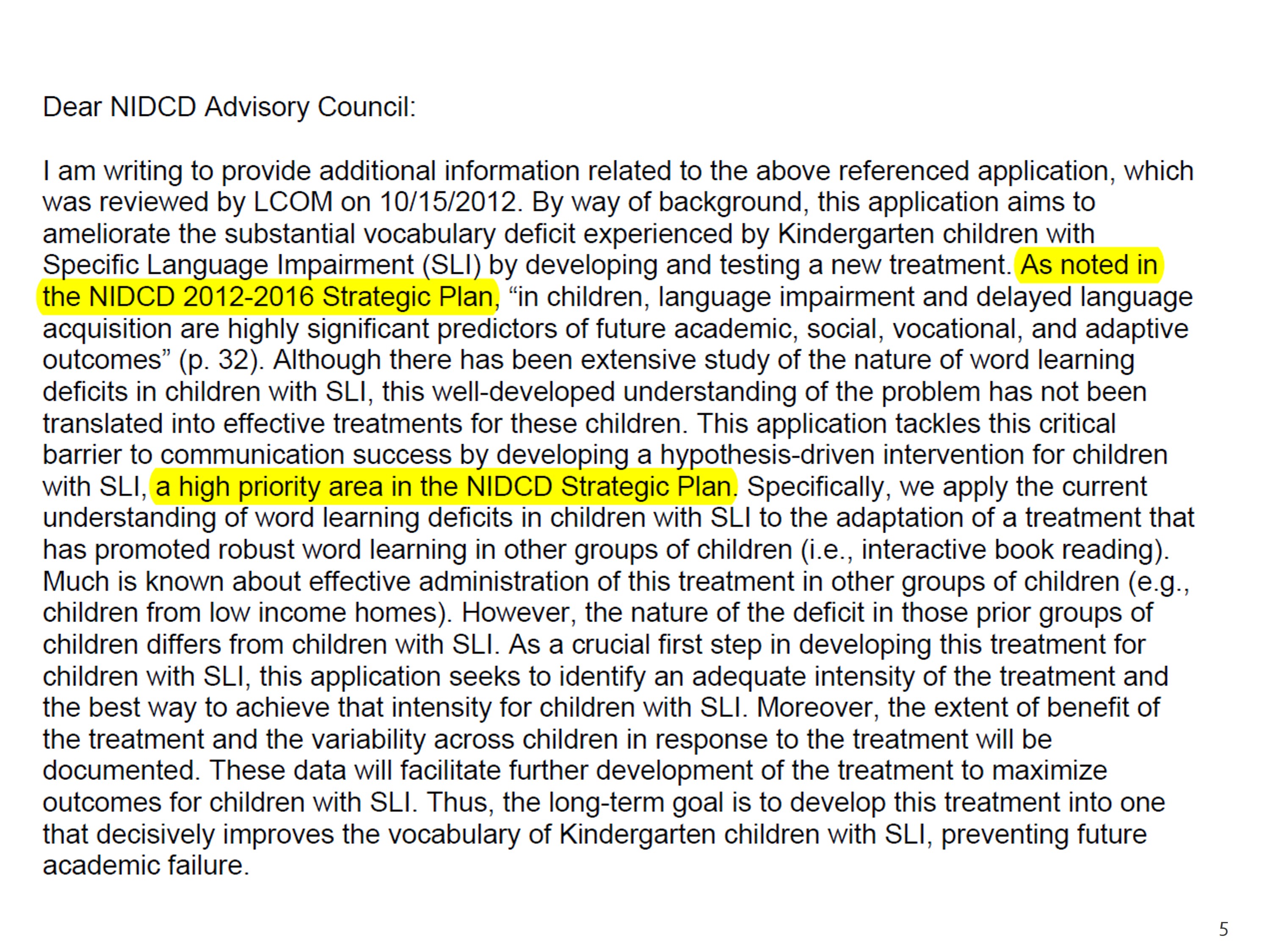

So here’s a letter that I wrote to Council. Again, this is just the introductory portion of it. This is from this book reading grant that you guys saw the abstract and specific aims from. So you can kind of compare maybe how this intro to the letter looks a little bit different from what’s in the abstract and specific aims slides.

It just starts off by again kind of setting up what the grant is about to advocate for it. And the things that are highlighted in yellow is where I’m trying to tie this to the strategic plan. So it even has a little quote from the strategic plan about the importance of looking at children with SLI, the importance of developing hypothesis-driven intervention techniques. All of that straight from the strategic plan. So you really want to show how the work you’re proposing ties into the strategic plan of NIDCD so that your Council member can start to advocate for you, in terms of how this is high program priority.

The strategic plan is updated every three years. And it’s on the website. So it’s easy to find.

I won’t read this to you, just in the interest of time, but you’ll see that it has a lot of the same elements that you saw in the abstract and specific aims, but written again in a way that should be very accessible to anyone who has any kind of interest in communication disorders, so trying to avoid a lot of jargon, trying to really sell the importance of the work. So you want to write something like that, that kind of casts your work in a bigger picture and does that self advocacy for your grant. And then after this section, what you’re going to do is now kind of respond to the reviews in the same way that you do in an introduction to resubmission. And so, we’re going to look at some of those specific things.

William Yost:

Everything that we’re going to talk from now on in about applies either to the letter or to the revision. The cover sheet, the one page you have in revision to address the concerns. So there’s no difference here. All the caveats, everything we’re going to talk about apply equally to both kinds of correspondence.

Holly Storkel:

And just another note, too. My program officer offered to read my letter before I actually submitted it and I definitely took advantage of that, so. And just as we’ve said for other things too, you would want several people to read that letter even before you gave it to your program officer. It’s not something that you just, you know, zip off in a quick 30 minutes. This is the thing that’s going to determine whether you get funding or not.

And actually, just as a follow up to that, I did get kind of the good news, bad news call after that, where my program officer called me and said the good news is you’ve been recommended as high program priority. The bad news is I don’t know exactly when I’m going to be able to pay your grant or how much I’m going to be able to pay it or whatever. I could call you tomorrow and tell you that it’s paid or I might be calling you in — I think we were talking maybe in the spring — and she said or maybe in the fall I’d be calling you, you know. I’m not really sure. And, in fact, she did call me the next day to say it was going to be funded and funded at pretty much the same level.

William Yost:

And that discussion’s more likely to happen these days because of the crazy budget world we live in. When NIDCD or any part of NIH or the VA or any place doesn’t get a budget or gets a continuing resolution, they become extremely conservative. They don’t want to burn their money in the first cycle and have nothing left for the second and third. So they’ll underspend maybe a lot in the first two cycles, hoping that that was conservative and they will in fact get some reinstatement of a budget towards the end of the fiscal year, which ends in October. So oftentimes, you get a call in September and saying remember back in January when we had this conversation? Guess what? We’re going to fund you because of this very, very late money, okay. So yes, indeed, it can be in some instances a very long time between when you first talk to your program officer and got the good news and then got the not so good news. It may be a long time.