The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

I’m going to talk a little bit about conceptual frameworks. There’s lots of them. The challenge is making sure you’re using something that really addresses your particular implementation question.

I’m going to talk about a model that I developed with some colleagues where we had this phased model over time that talks about multiple system and organizational levels. I’m describe some studies both in terms of their design for addressing implementation questions at different levels, but also addressing effectiveness or efficacy while assessing implementation issues as well. I’m going to describe those studies in different settings. So that’s where we’re going.

When I think about implementation science, it’s a broad field. There’s lots of traditions that inform implementation science. My particular take is from policy organizations and how that impacts it. But there’s lots of different approaches that you can use when you’re thinking about this. All the way from social network theory, how interventions move among populations of providers or clinics, or how organizations network. To much more top-down policy: how policy mandates impact what’s being done in particular fields, especially if you’re working in school systems, how policies can affect what can be done in schools and in special education. And some of my colleagues that I work closely with, Aubyn Stahmer and Lauren Brookman-Frazee, work very frequently with school systems. They focus on implementation for autism spectrum disorder interventions in school systems.

Implementation Frameworks and Strategies

I like to make a distinction between frameworks and strategies. A framework is really a proposed model of factors that you think are likely to impact implementation and sustainment of evidence-based practice. It’s a theoretical model. A good model should identify kind of the key factors that you may want to address in a research application, or in improving care.

I will probably make this point a few times: if you’re putting together a proposal and thinking about that it’s really important to tie your framework in throughout your whole project. So that your theoretical model leads to your approach, how you’re going to address it. But also to all of your measures and your outcomes and implications for the field. It’s not just, “Hey we got our framework.” I’ve seen a number of applications as a reviewer for NIH that people say, “We’re using this framework,” but then the rest of the proposal doesn’t tie in. It really needs to be cohesive. So you need to think carefully about your frameworks as your thinking about implementation science.

And in contrast, the strategy is really a systematic process of the approach that you’re going to use to adopt or integrate an evidence-based innovation into usual care.

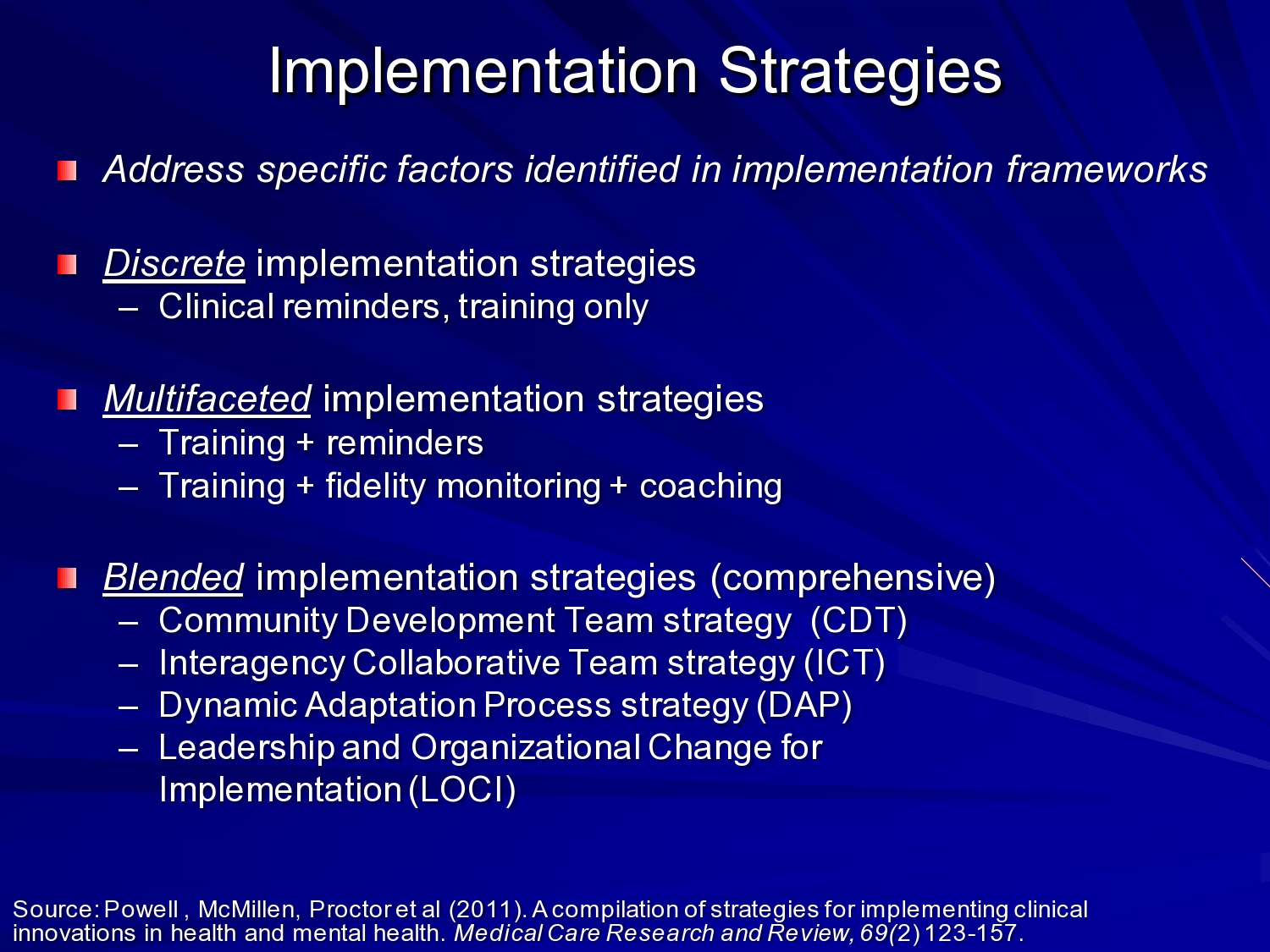

Byron Powell and colleagues at Wash U did a nice review of implementation strategies and identified what they called discrete, multifaceted, and blended — getting more complex as you move down that continuum.

An example of a discrete intervention: I worked with some folks at the VA on implementation of an HIV clinical reminder. And that implementation strategy was designed to increase HIV testing among at-risk veterans. And so the intervention was a software program that would go out when a vet was coming into the VA, no matter what service they were coming in on. It would go out, look at the medical record, identify risk factors for hep C and HIV, and if it met a threshold, then the nurse or physician would get electronic clinical reminder to invite the vet for testing. So there’s an example of a very discrete strategy that’s targeted at point of care.

There are also multifaceted implementation strategies. So you might have a clinical reminder, but also build leadership support to support physicians and nurses in actually using those clinical reminders. Because there’s lots of clinical reminders, so what do they attend to in that process.

And then blended implementation strategies are even more comprehensive in terms of you know building collaboration, building buy-in, coming up with specific strategies, and really melding all of those together.

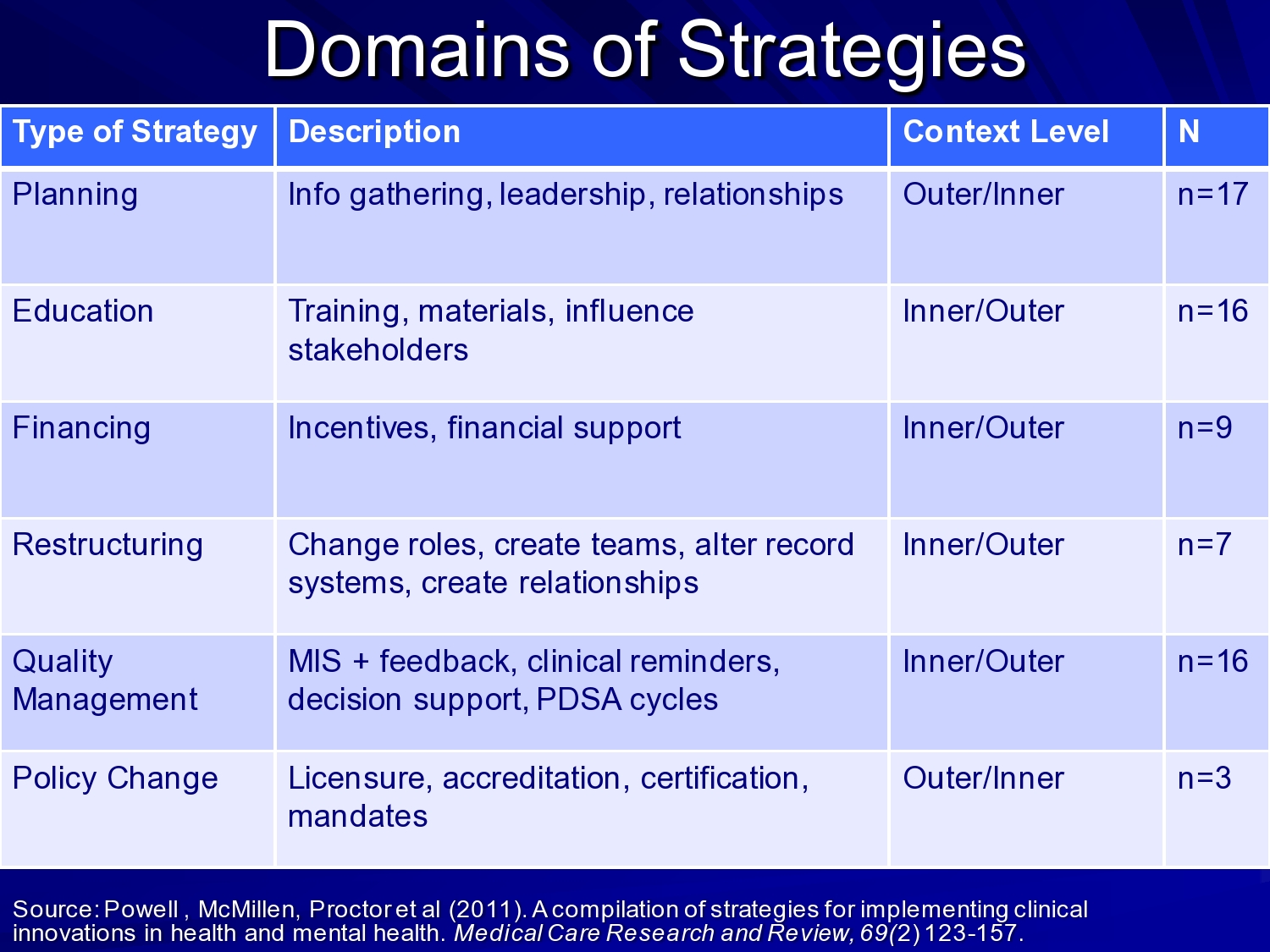

Byron and his colleagues really identified these domains– planning, education, financing, restructuring, quality management, and policy change — as types of strategies within those different levels of intensity or comprehensiveness of strategies.

I don’t want to belabor this, but it’s important to think about your frameworks, and then how your strategies may fit into your frameworks too. Because you want a strategy that’s congruent with your theoretical model of change. If your theory says it’s all happening at the clinician and provider level, then your strategy should address that level. Just some things to think about as you’re planning your work.

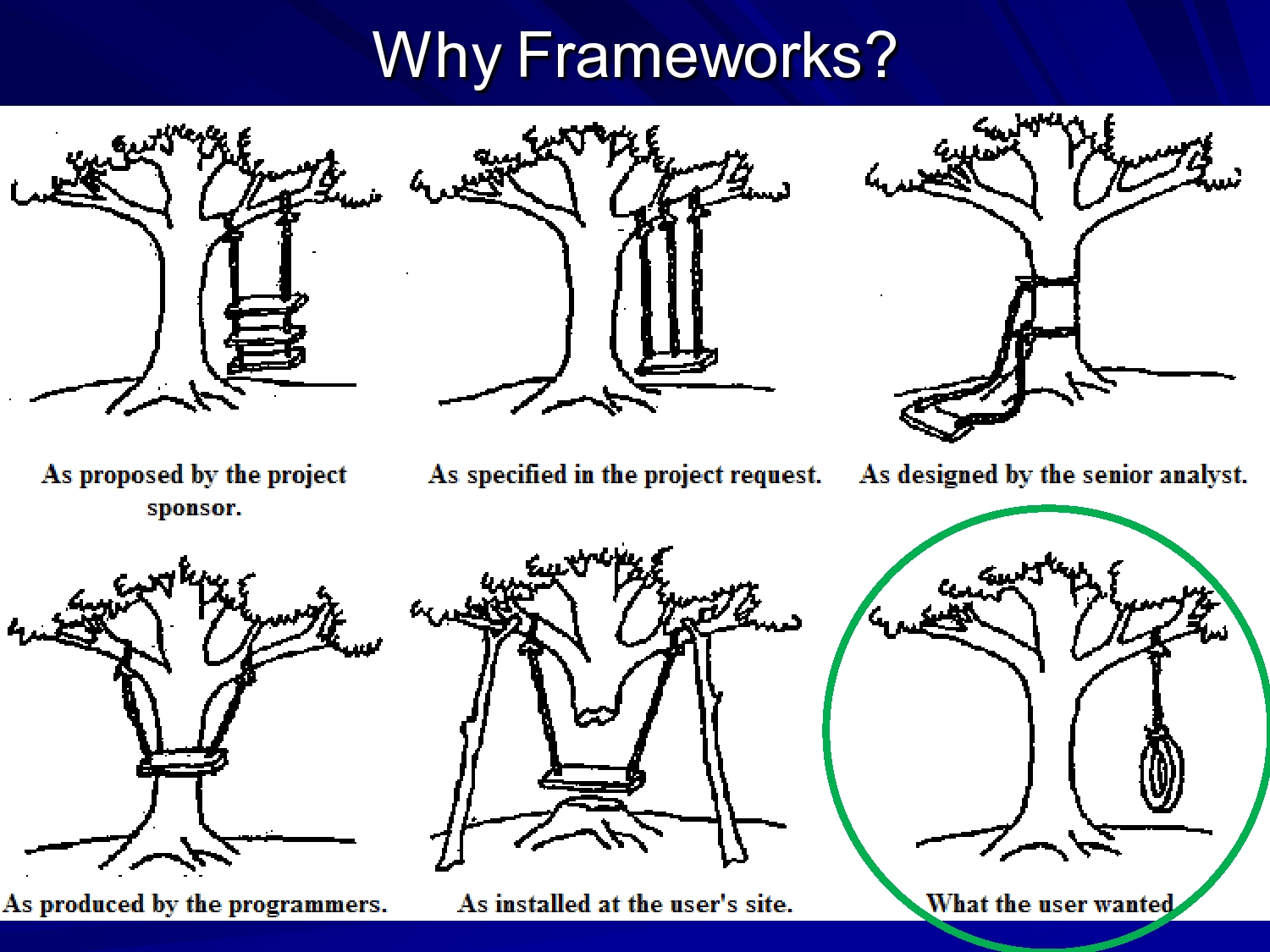

Why do we want frameworks? Well if your goal is to have a simple tire swing on the tree you may propose that, but then if you ask your engineer to design it you may get something different from what you really wanted. So hopefully, the framework really guides your thought about what you’re looking for, how you’re going to get there, and what the end product should be. We often think of frameworks as static, but your framework should be able to also help guide your process and what you attend to as your implementing evidence-based practice.

So also coming out of the hotbed of implementation science at Wash U, Rachel Tabak, Ross Brownson, and David Chambers did a review of implementation frameworks and models. They identified 61 different frameworks to review. I think you probably were exposed a few frameworks yesterday, but there’s lots out there to select from and think about what fits what you’re working on.

They evaluated frameworks on construct for flexibility, focus on dissemination versus implementation, and socio-ecological level whether it was individual, community, system. But many frameworks span these different levels. They really, in a table, outlined some of the frameworks across some of these dimensions. So it’s a really useful resource.

I highlighted just a few here, the consolidated framework for implementation research developed by Laura Damschroder and her colleagues at the VA. The ARC (availability, responsiveness, and continuity) developed by Charles Glisson to support his organizational change intervention. And then our EPIS or conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation.

And I want to say at this point that with your particular research questions, your framework selection becomes important depending on where you’re going to submit your grants, where you’re going to go, and what the accepted or understood frameworks are.

I was working with some colleagues on a hep C application for the VA. And we used my framework — of course I want to use my own framework — but it didn’t quite fit with the paradigm in the VA. The reviewers at the VA were much more familiar with the CFIR framework. So in our revision, we changed frameworks and modeled our methods to fit that conceptual model. It’s not just how your framework fits, but it’s also grant strategy and development strategy to make your work as competitive as possible as you move forward.

So I’m going to talk briefly about the use of levels and phases. We see in many frameworks these common elements of multiple levels. Often implementation occurs in complex systems. Complex systems means you need to decide what you’re going to attend to.

I worked on a project with Sheryl Kataoka up at UCLA on implementation of cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in the schools. It was in middle schools in LA Unified School District, and what we were doing in that developmental study was looking to see if we could use Katherine Klein’s implementation model which was developed for the implementation of software technology in manufacturing plants and bring that in. This idea of creating an implementation climate in the schools, and we combined that with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s collaborative breakthrough process to try to see if that was an acceptable way to build buy in for implementation of CBITS in the schools.

We had to think about the school district. So on our collaborative team on the project we had mental health director for LA Unified School District. We also had provider organizations present, and their directors. We had the researchers and developers of the CBITS intervention, and also input from the actual service providers who go and deliver in the schools. So we’re thinking across school district, school principal buy in, community-based organizations, researchers, providers. So all of those levels, for us, were important in this process.

That’s just one example of thinking about how multiple levels. Because if the school district has a policy that’s at odds with what you’re trying to do, it is very difficult to get change to occur regardless of whether you have a charismatic principal at one school, or your know, in one district a district superintendent that’s supportive. Or you may have district superintendents that are not supportive, or principals that don’t buy-in. So all of those levels are important in the implementation process. It’s important to identify concerns at those different levels.

I also think about implementation in terms of phases over time. And different models have different names, but essentially there are phases related to identifying problems, thinking about how you’re going to address those problems, actually implementing change, and then sustaining change. So there may be issues in those different phases that you attend to more or less as you go through the implementation process. Or your implementation project may focus on just getting people ready to implement, or it may focus just on actual implementation.

The phased approach kind of helps me think about what I want to do and what do I want to address in the implementation process. And at the, towards the end of the talk I have a model of how we’ve been trying to create a process for doing that.

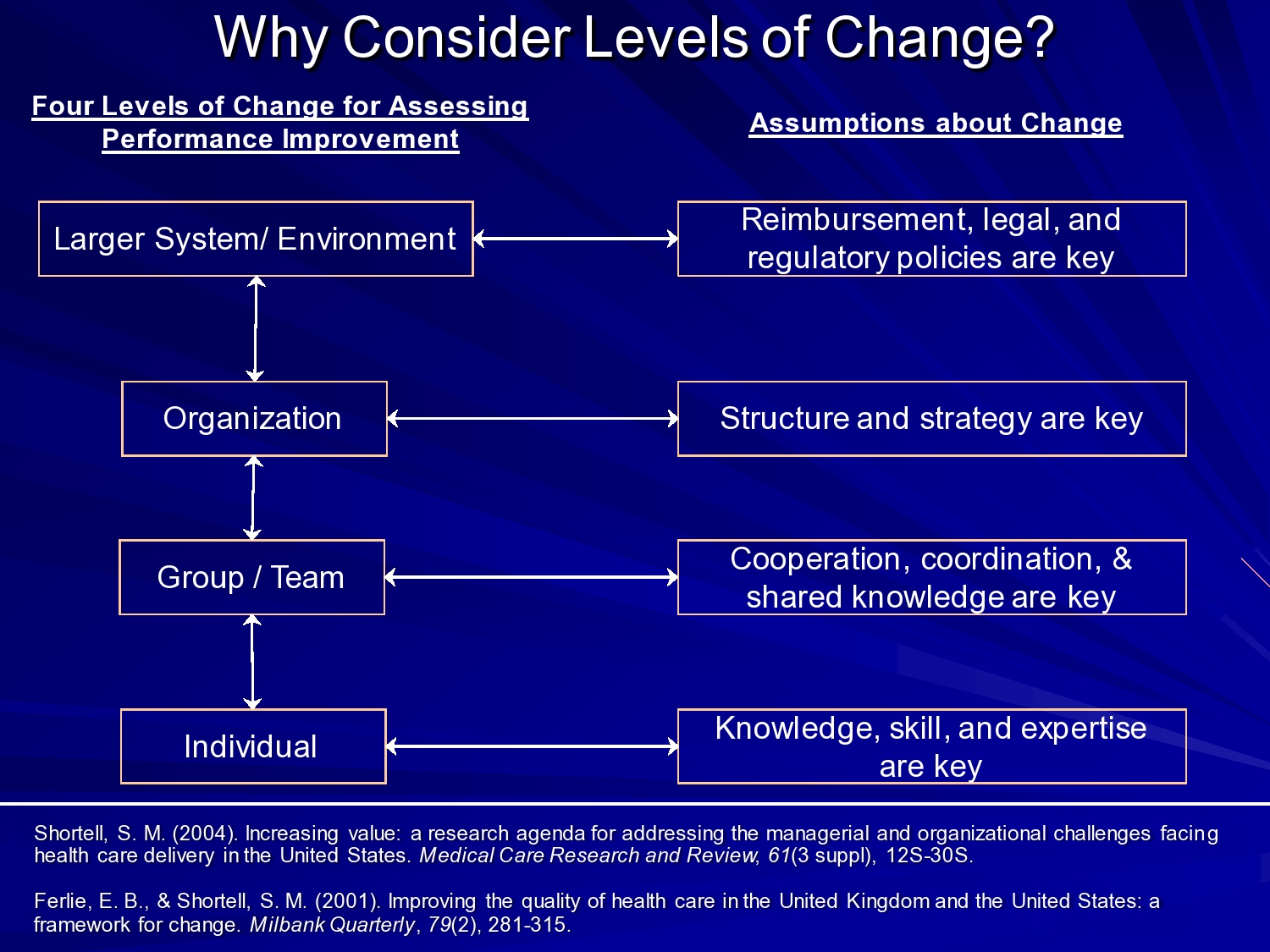

This idea of levels of change I mentioned to you, it’s not new. Steve Shortell and Ewan Ferlie talked about this in regard to quality improvement in health care. And identified some issues in the larger system environment. Reimbursement, legal and regulatory policies and the organization structure and strategy. I think in mental health and social services we also see organizational, culture, and climate in leadership is important at this level.

But also at the group and team level. How teams and workgroups work together. This has really been shown by Amy Edmondson at Harvard Business School who has done some really interesting studies looking at implementation of minimally invasive cardiac procedure in surgical teams. And what she showed is where you had a strong physician leader who created a climate of psychological safety, and support, and problem solving among the team. They were able to successfully implement minimally invasive procedures and sustain them. Whereas, in teams where that was not the case, where you had adversarial relationships, where people were afraid to speak up actually went back to more invasive open-heart surgery, incision, open the chest, and do the heart surgery. So when you think about that in terms of the impact of these implementation factors on patient care and patient process it’s a really critical application of implementation science.

And at the individual level, I think this speaks more to provider’s knowledge, skills, and expertise. But also to those receiving services. So we see also advocacy groups especially around ASD that are very important and sometimes shaping policy and shaping views of what’s acceptable in terms of practice. So these multiple levels can be really critical.

And then in terms of the phases, I talked about that. So I’m not going to belabor it.

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

CFIR domains are:

- Considering the characteristics of the intervention.

- The outer setting — this is kind of the policy or larger system setting.

- The inner setting within the organization.

- Characteristics of the individuals involved — and that can be the providers, clients, and also management. People who were involved in the implementation.

- And the process of implementation.

This came out of the VA, like I said and is a pretty widely accepted model.

What Laura did in her study — and this was early, she published this in 2009, so it was 2007 or 2008 when they were doing review of the existing models — they have a nice table that kind of lays out different frameworks, similar to what are Rachel Tabak and her colleagues did. But it lays out the different elements of different frameworks. And then pulls them together to the CFIR.

Availability, Responsiveness, Continuity (ARC) Organization Improvement Model

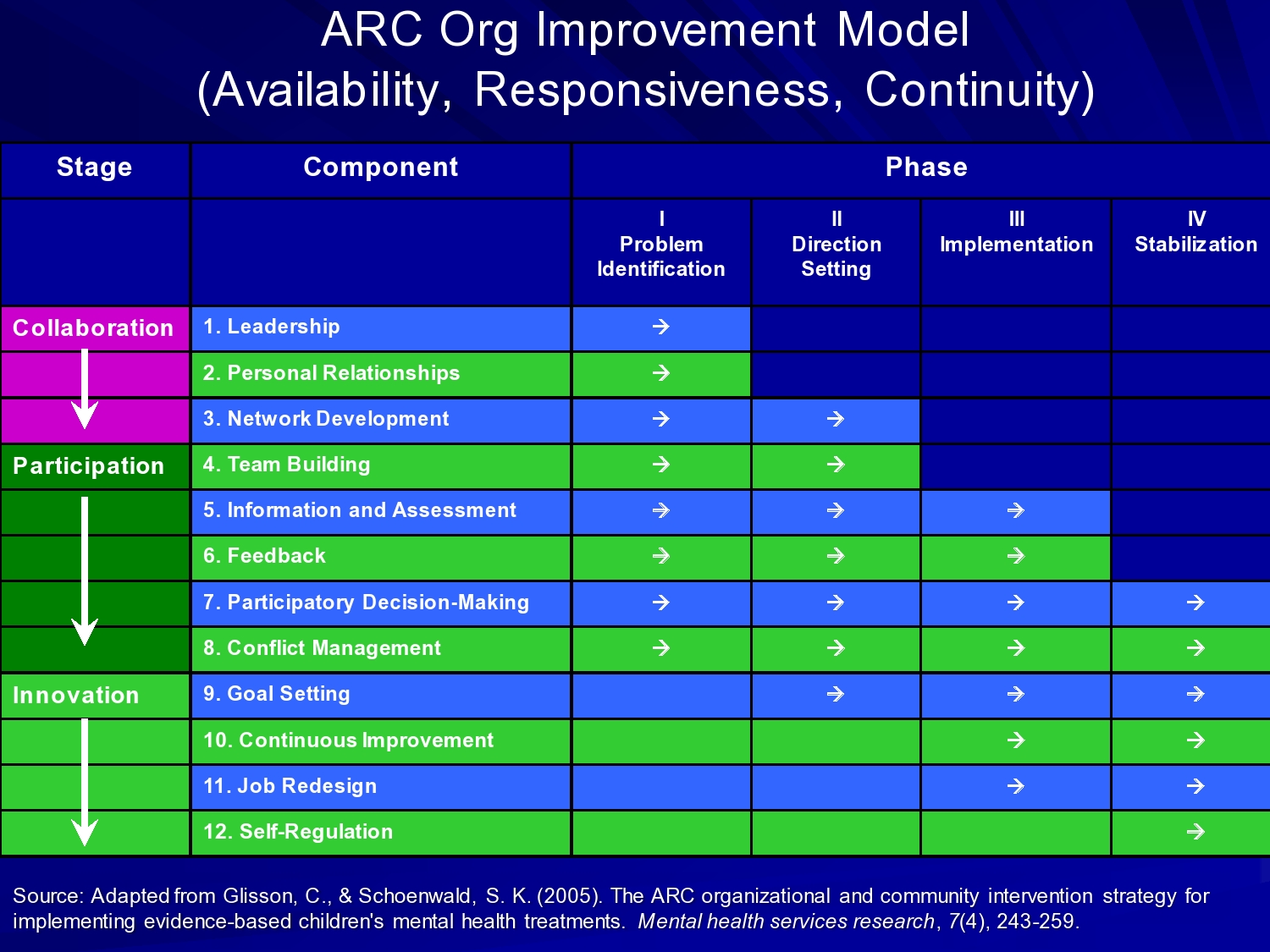

In Charles Glisson’s approach, he’s got stages of collaboration, participation, and innovation across phases that we think of as implementation phases. Problem identification, direction setting, implementation, and stabilization — which you can think of as sustainment, or sustainability.

But then the components that he works in on in his ARC organizational intervention, are things like leadership, and relationships, and networks within organizations and across organizations, teambuilding, developing information and assessment, feedback processes, participatory decision-making.

Conflict management, which I think is an important one. Some of our recent qualitative work has looked at the process of implementation over a large service system, and what we’ve seen is initial kind of buy in and collaboration, and then as things get going peoples, different stakeholders own agendas, and interests, and needs kind of come to the fore and then negotiation occurs. And in a successful implementation, those are resolved and coalesced, but you kind of have to be prepared. I’m going to talk about this a little bit with the problem-solving orientation. The problem-solving approach in implementation. It’s not like you’re going to set it up and we’re just going to go, and there’s not going to be problems. All those things have to be worked on in negotiating.

So goal setting, continuous improvement approach, and job redesign, and self- regulation are the components of Charles’ model. And I’m going to talk about outcomes of one study of his model in a little bit.

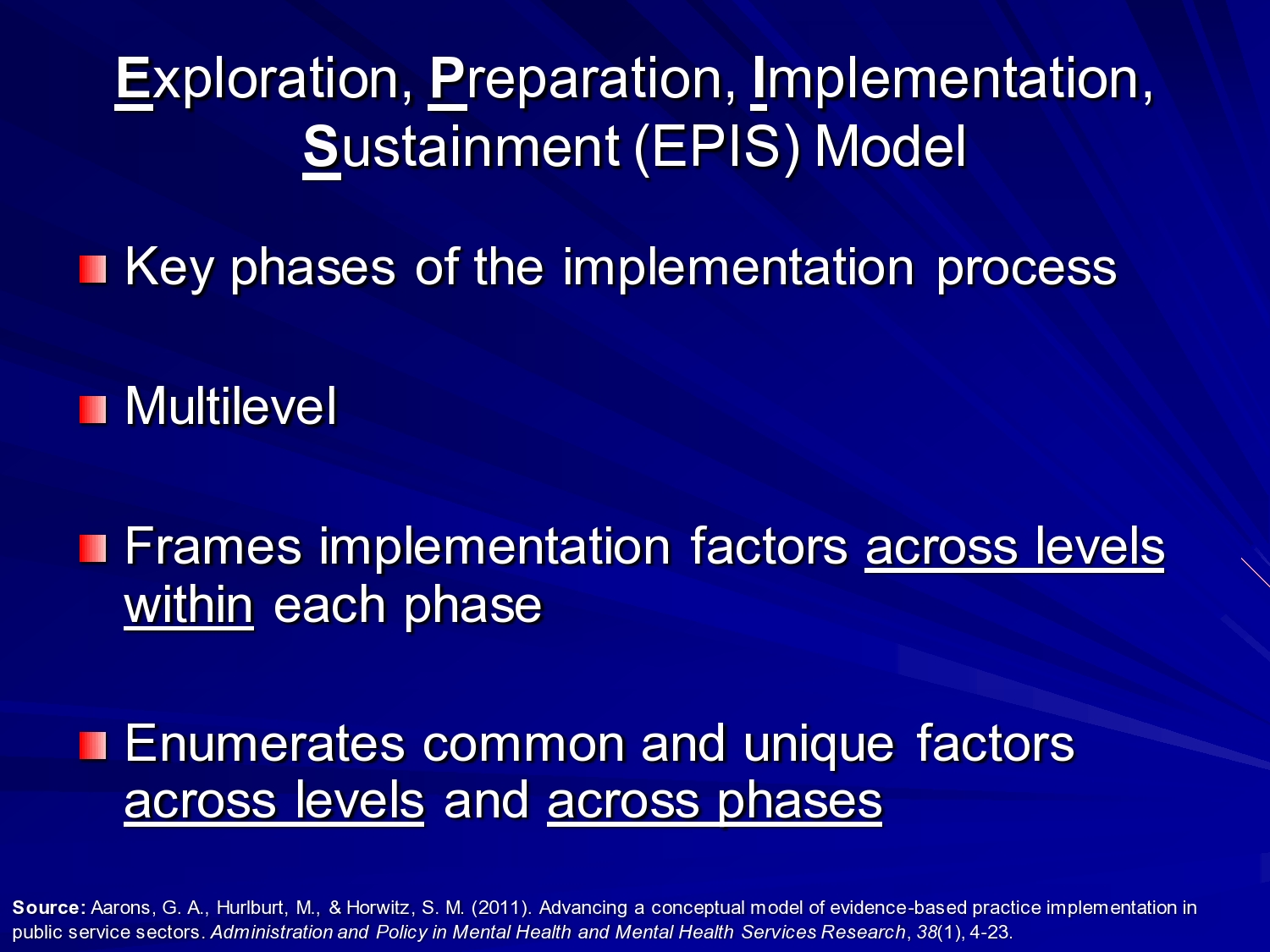

Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) Model

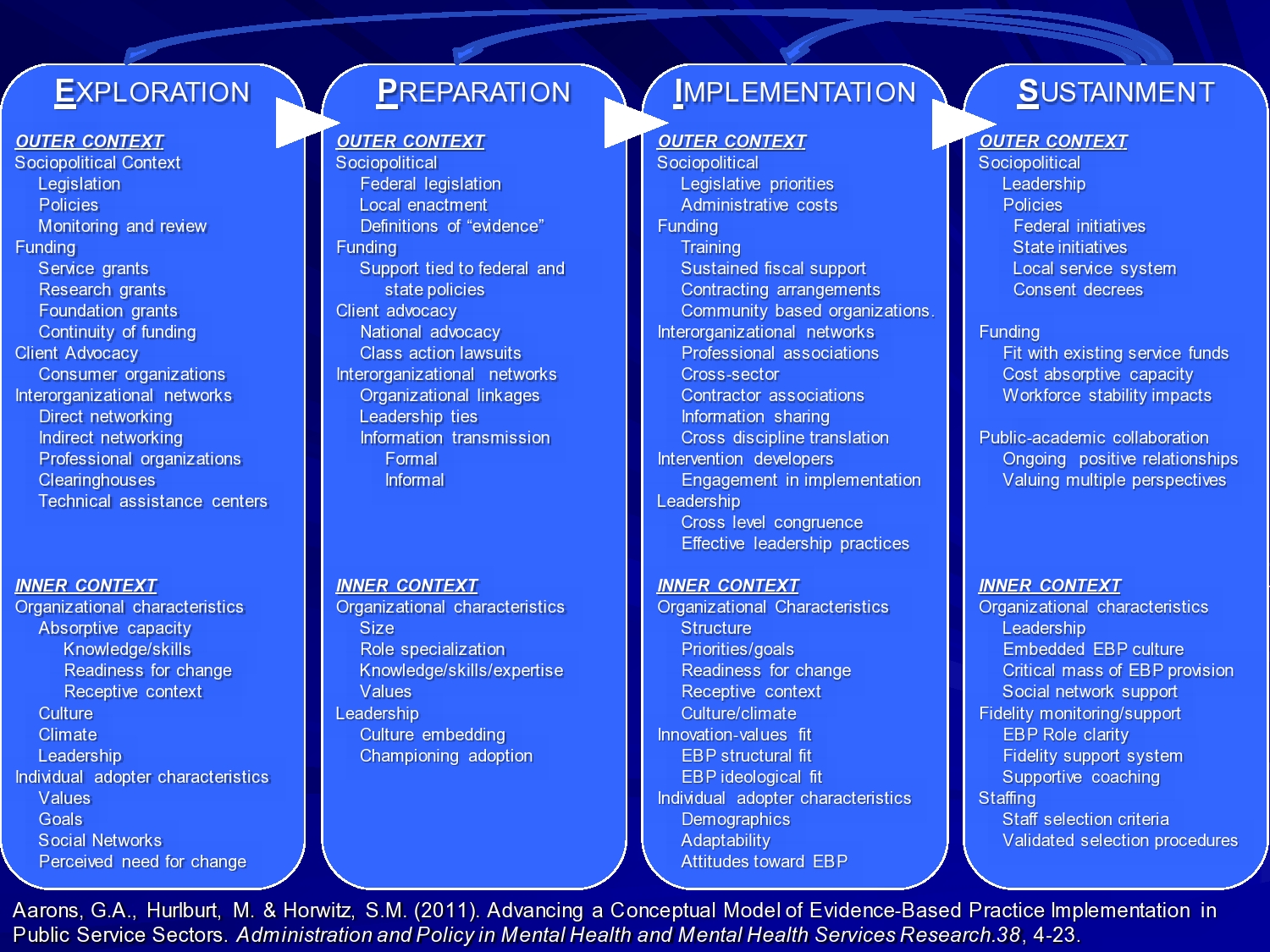

In the EPIS — this is the framework I developed with Mike Hurlburt and Sarah Horwitz under the implementation methods research group. John Lansford was PI of that center. We identified these four phases: Exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment. Within each of these phases, there are certain outer context or system issues to consider, and inner context, or within organization and population issues to consider as you move forward. So it enumerates common and unique factors across levels. And in the model there’s a lot of stuff.

So with this model what we tried to do was, based on a review of the literature, identify most of the things that we could find that are important based on existing literature in these different phases and across levels. But this is not meant to imply that you need to address every single thing. The idea is to think about for my particular intervention that I want to implement, in a particular setting, across these phases of exploration, thinking about what we’re going to implement, preparation, identifying the barriers and facilitators, and addressing those. Actual implementation where we’re beginning training, doing fidelity assessment, those sorts of things, and in sustainment how do we keep this going after the grant funding runs out. What are the things we want to attend to across those phases for our particular study?

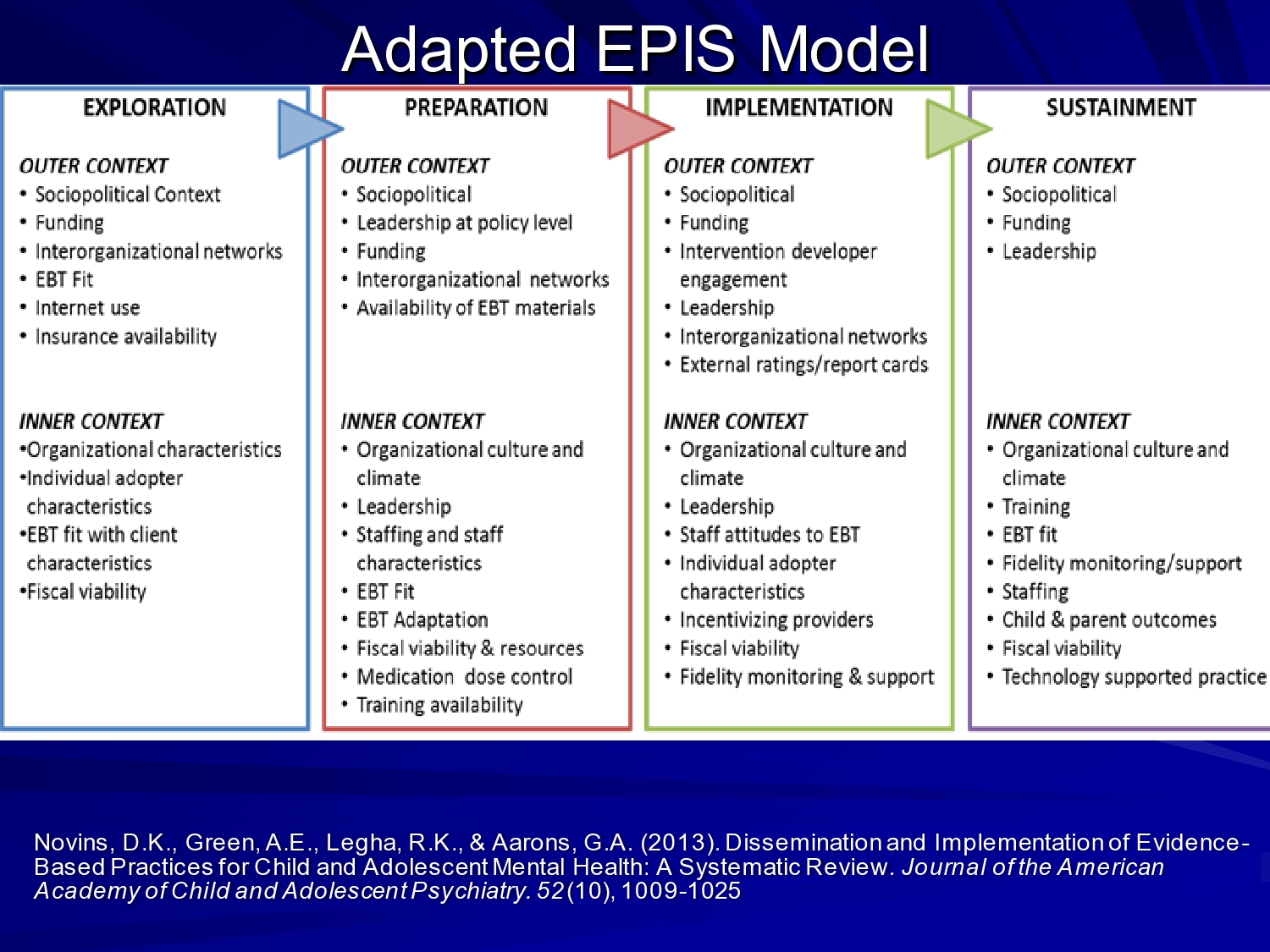

Doug Novins led a systematic review of dissemination and implementation studies in a children’s mental health, and for children’s mental health disorders. And in that review we identified these factors based on the studies that ended up in the systematic review. So you can see it’s winnowed down. And this is across studies. If we were to pick any one study and say what were the factors that were looked at in any one study, this list would be winnowed down even a little further.

So when you’re thinking about these frameworks it’s really important to think about your context, and your issues.

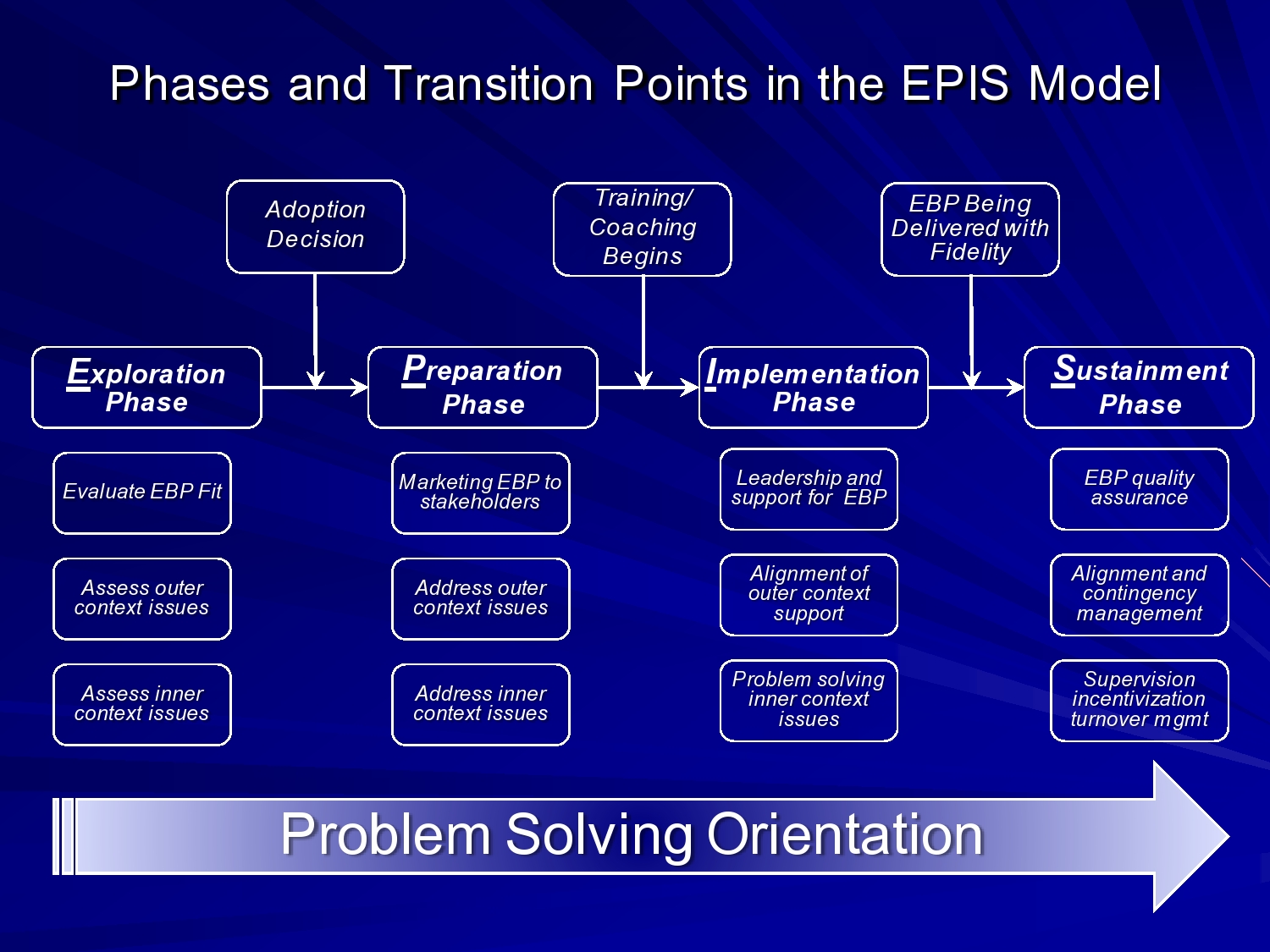

In the EPIS framework, I think about these transition points. So in the exploration phase you’re thinking about the fit of the evidence-based practice. Is the system ready? Are organizations ready? Providers, are they ready to go? What do we need to do to make this happen? Both in the outer and inner context.

In the preparation phase, once the adoption decision is made, then you enter the preparation phase. And then, you know, we’re marketing to stakeholders. We’re building collaboration. We’re really addressing the outer and inner context issues that we’ve identified.

And then once we’re ready. I should say when we feel ready, which we’re almost never really ready, you know the training, the coaching, whatever model — and intervention implementation begins. And then it’s a matter of, you know, alignment of outer context support and problem solving outer and inner context issues.

Once the evidence-based practice or intervention is being delivered, with fidelity or the level of quality that we’re comfortable with, then we’re really moving into that sustainment phase where we sustain this over the long run. And I keep putting this problem-solving orientation and I’d like another bar that says you know, in this phase should be thinking about sustainment. So in exploration you should already be thinking about sustainment. It’s not just necessarily a demonstration of efficacy or effectiveness, and we may not be doing an intervention for sustainment. But we may want to be attending to factors in our research design across the way that are going to help us sustain an intervention once we get through our trial.

Mixed-Methods Research Approaches

So we’ll switch gears. Often in implementation studies, especially hybrid studies that pair effectiveness and implementation issues, we want to use mixed methods. There’s a lot of interest in mixed methods, and they’re part of many training programs in implementation science as well, including the Training Institutes on Dissemination Implementation Research and Health, sponsored by the NIH and also the Implementation Research Institute training grant.

I like to use mixed methods, and it’s interesting because when I came out of grad school, when I was doing my post doc, I was quant jock. I had done five graduate statistics courses, and I remember doing structural equation models by hand in graduate school. And I thought that was a badge of honor. So it took me a while to come around — but it wasn’t till I was really faced with understanding implementation challenges, kind of from the ground up. We can look at quantitative measures, but do they tell us the real story?

So integrating mixed methods. I was very fortunate to work with Larry Palinkas who’s up at USC now, medical anthropologist. Thinking about designing these studies and addressing some of the issues that we deal with in implementation studies where your unit of analysis may shift from a patient or from a client to a team or an organization. And suddenly your power to detect effects kind of dries up, because your unit of analysis really changes.

So it’s really important in thinking about design. If our quantitative design isn’t as strong as we would like, how can we strengthen it with the qualitative component? And what more can we learn and how can the two methods inform one another? You can answer confirmatory exploratory questions and verify and generate theory at the same time.

So in the study I’m going to talk about in child welfare system in Oklahoma, we did annual meetings where all of our stakeholders, including agency directors, and folks who were directing services in the community would all come to San Diego every year. And we would review our quantitative and qualitative data that we had, and do preliminary analyses, and we would talk about what that means, and what does it mean for the next phase of the study, and how are we going to integrate that. So we really were truly trying to mix methods, not just a quantitative component and a qualitative component and never the twain shall meet. But really bringing those together.

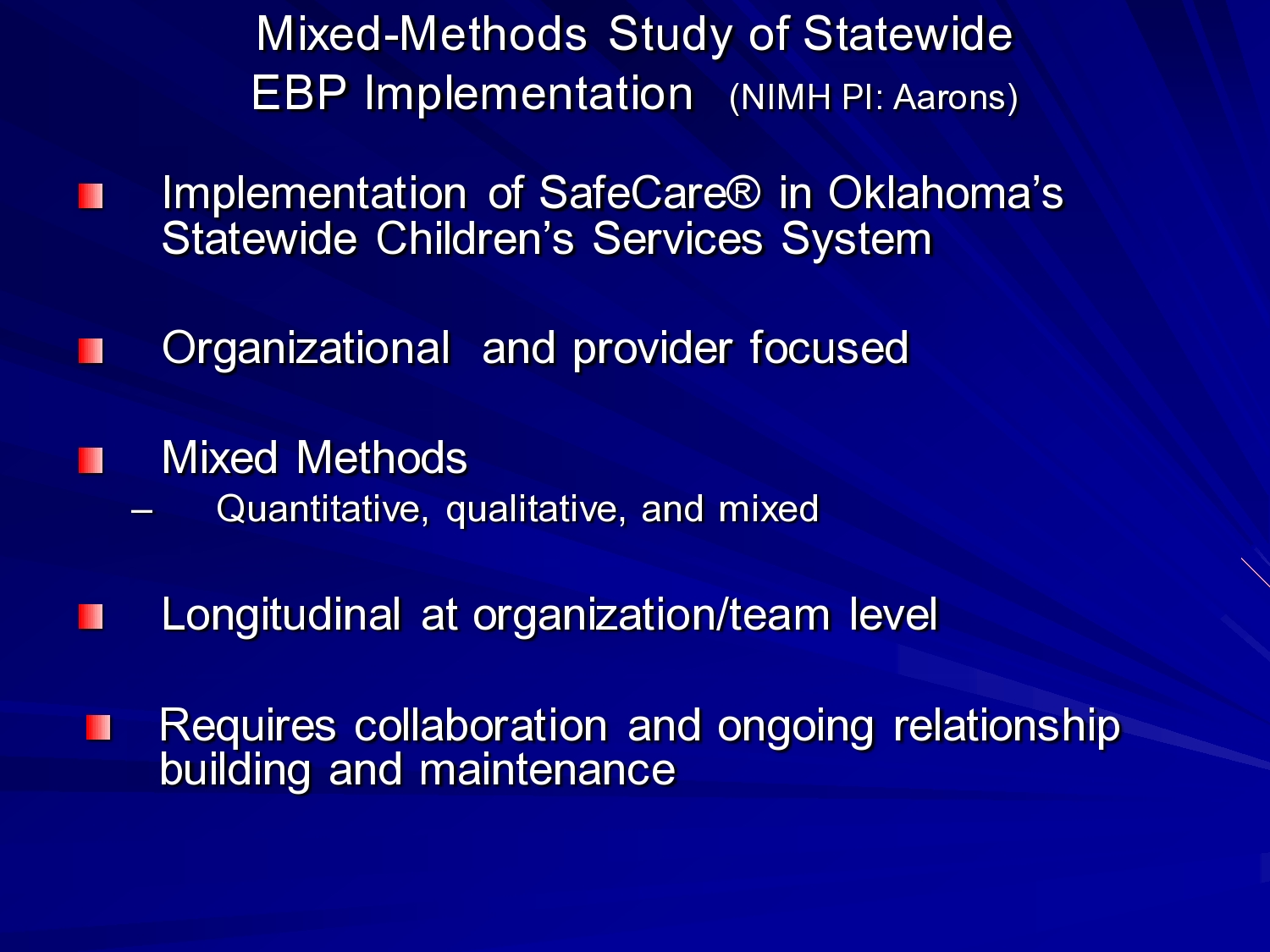

So I want to talk about this mixed method study of statewide EBP implementation. This is an implementation of SafeCare in Oklahoma’s statewide children services system. SafeCare is a child neglect intervention. In child welfare 65 to 75% of cases are because of child neglect. And while abuse, physical abuse and sexual abuse really hit the headlines, there are more child deaths from neglect than other forms of child maltreatment. And it’s as I said, it’s just highly prevalent. It’s the leading reason for families to become involved with the child welfare system. And in addition to harm to children in terms of you know, physical harm, emotional harm, there’s also development delay associated with it, poor functioning, poor school functioning. Lots of other outcomes in childhood and adolescence that are a function of a child neglect.

The study was mix methods of quantitative and qualitative. So we were doing quantitative assessments of the organizations, trying to look at things like leadership at the team level, culture, and climate of the teams, and how that impacted providers. And out qualitative methods involved focus groups with providers and interviews with agency directors, area directors and the child welfare system folks. Because we were interested in this statewide implementation of all the factors that might impact how it’s implemented and sustained. So it was longitudinal at the organization and team level. We actually with a no-cost extension, followed these teams for 6 years, 12 waves of data collection, with a 95% or better response rate across all waves. It really required ongoing collaboration and working in the trenches, and being able to say to the organizations in the service system we have something to give back and to share as we go forward and we’ll do this process together. And I think that was really helpful in the engagement process in the statewide system.

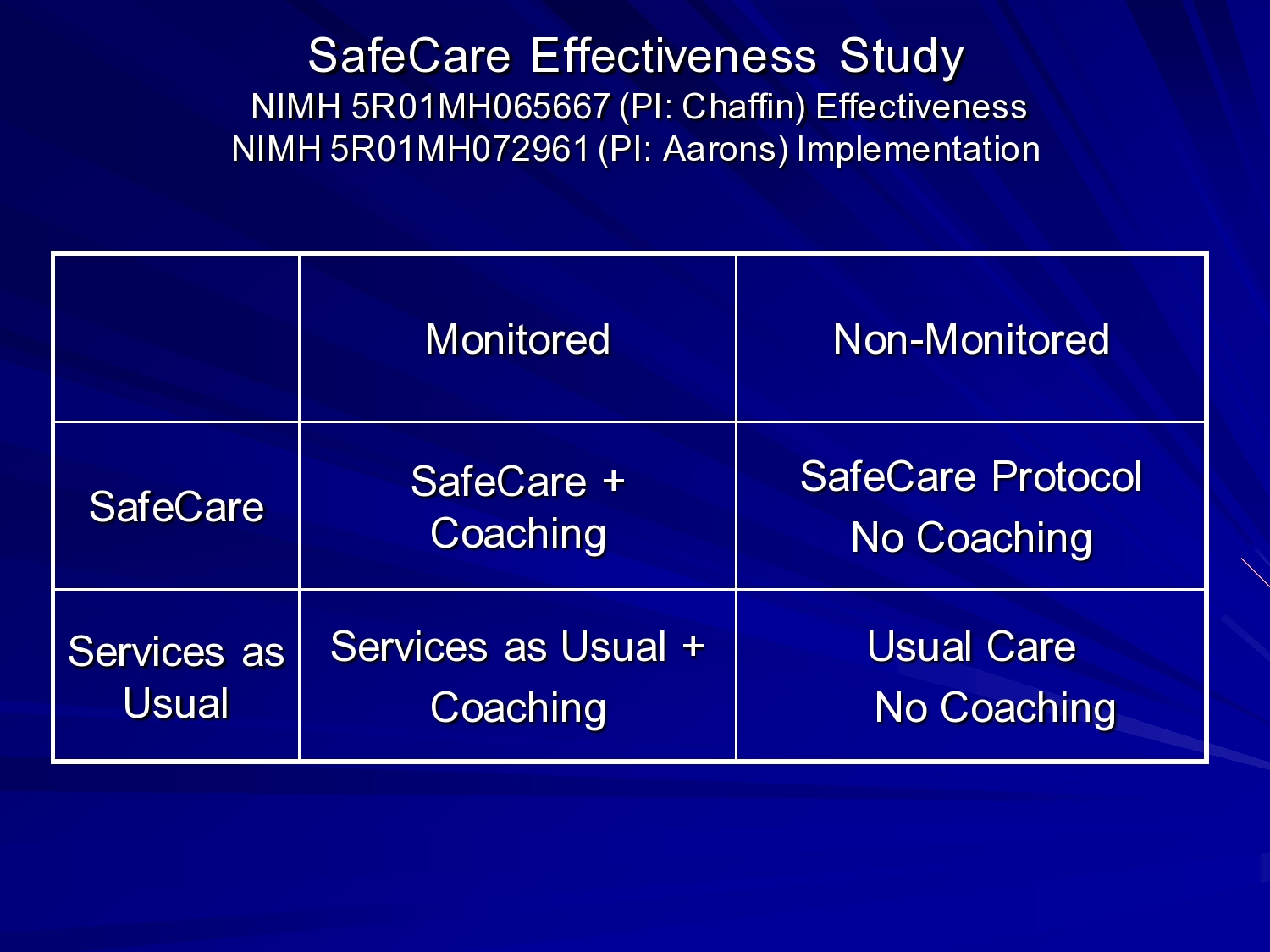

So I built this on top of Mark Chaffin’s, at the University of Oklahoma, effectiveness trial of SafeCare. They had assigned teams, and they had to do assignment of teams versus just randomization because of differences in regions.

So randomization. Everyone thinks randomization is the gold standard. Yes? No? I don’t know? Reviewers often do, and policymakers often do. But randomization is based on the law of large numbers. If you had 6000 regions I’d say yes randomize. If you have six, you’re going to get inequities. So there was experimentally controlled assignment.

The red is the teams that were implementing SafeCare, and the green were usual care, regular home visitations. This is all home visitation services, where the home visitor would go once a week, meet with the family and work with them. So and services as usual was fairly unstructured. Go in, try to assess what problems there are, and address those problems. Whereas with SafeCare there’s really a focus on home health, home safety, and parent-child interactions and improving the communication interactions between the parent and child or the parent and infant.

So in the study, there was the SafeCare condition and then teams within SafeCare or services usual were randomized to coaching or no coaching. So this is the fidelity monitoring, fidelity assessment piece. A coach would go out with the home visitor in the home, observe them, and then coach them on the model. Or you know kind of demonstrate different activities and things like that.

So Mark and Kathy Simms came out to our center to talk about the study that they were doing. And in our discussions we thought, wouldn’t this be a great opportunity to look at implementation issues.

This is something we were talking about earlier. You can be opportunistic in terms of thinking about implementation studies. If there, for example, is a policy change, or if a state decides to implement something broadly, can you build an implementation study on that? Can you work with the policymakers or agencies to bring in a particular practice that’s going to improve care? And then can you build a study on top of that?

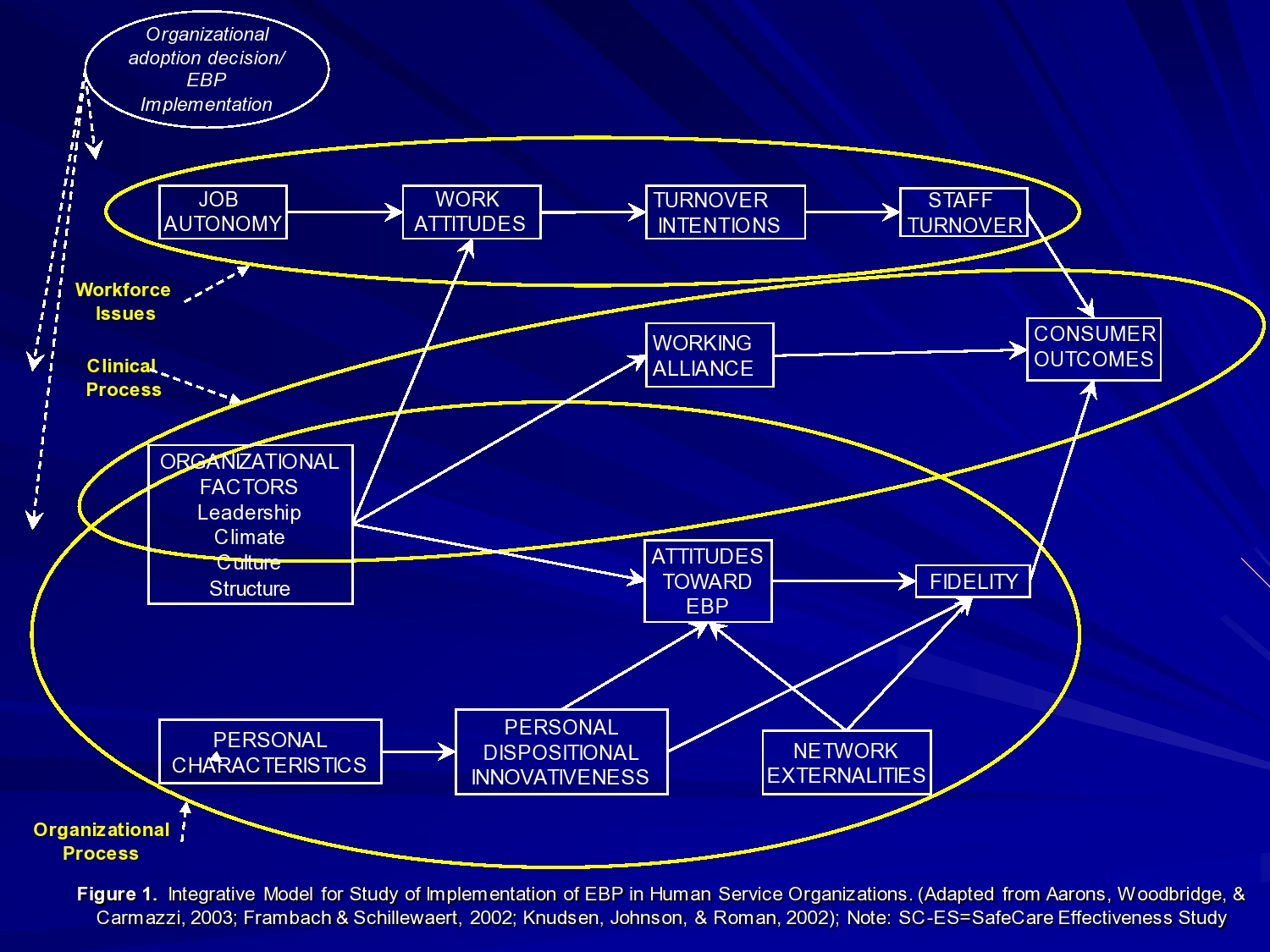

So I proposed this R01 in which we wanted to look at workforce issues. The impact of implementing on job autonomy and work attitudes. People’s perceptions of their work. Because they were used to just being able to go to the home, do their assessment, do whatever. And now you’re imposing an evidence-based intervention. Very structured, manualized, and not only that, but for half the teams, someone was going out to watch them and observe them doing their work. So we thought it, you know, reduced job autonomy, probably reduced work attitudes, and increase staff turnover.

We also wanted to look at things like clinical process, like what happens with working alliance of the relationship between the provider and their clients when you’re doing a more structured intervention.

Organizational factors. Like I said, leadership, culture, climate, and structure at the team level, and then look at. So that’s the clinical process piece. And then the organizational process is the organizational factors and how it impacts the individual provider’s own adaptability, flexibility, their attitudes towards evidence-based practice. The fidelity with which they’re working on the model, and then ultimately outcomes.

And we’re actually trying to put a model together to look at a lot of this stuff together, but we had looked at some of those outcomes separately.

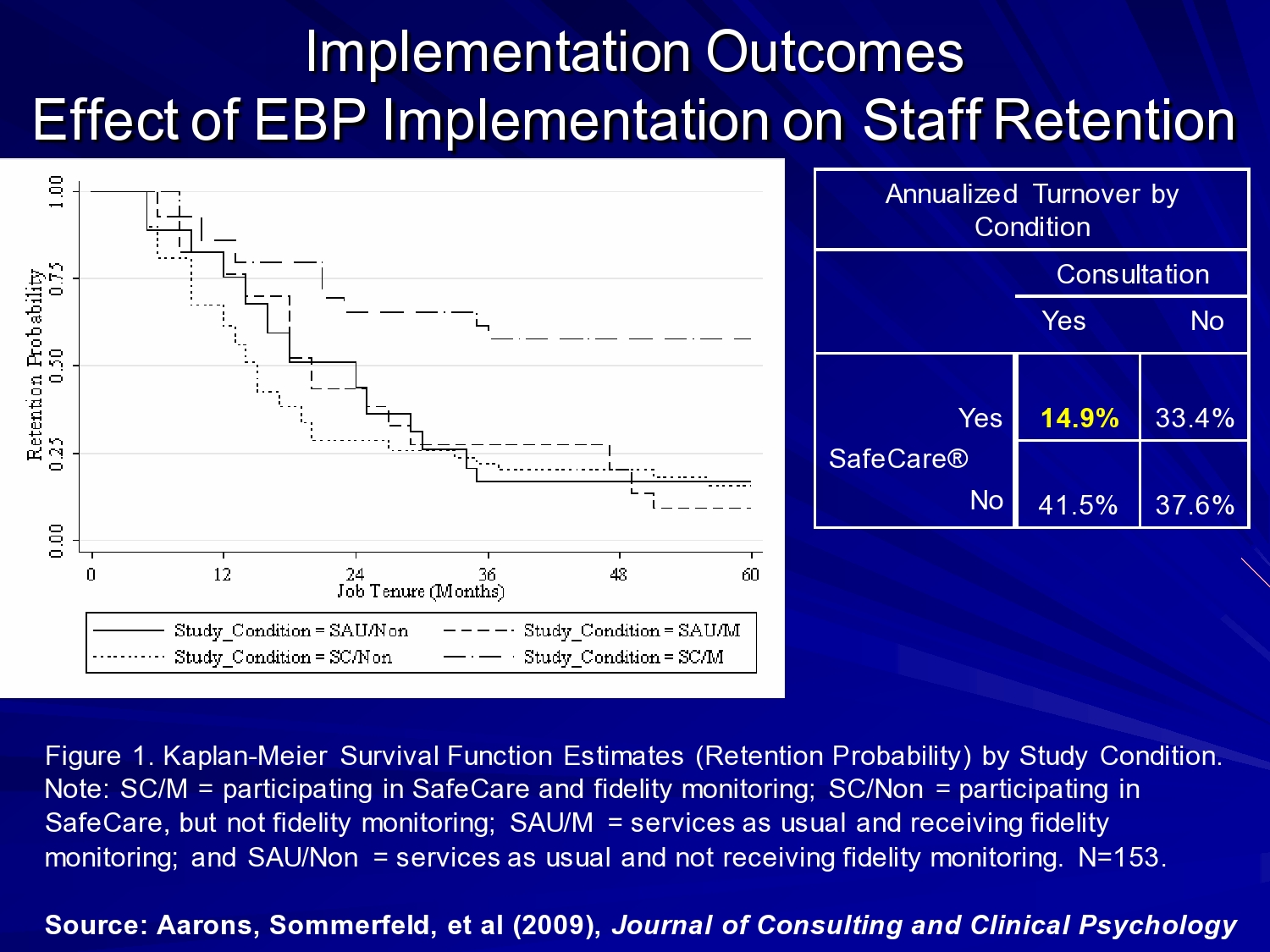

The first quantitative piece we published was looking at the effect of the evidence-based practice and coaching on staff retention. And we had hypothesized that in the SafeCare condition with coaching, you would have reduced job autonomy, and you would have higher turnover rates among those teams. And we found exactly the opposite. This is a survival analysis. This is the SafeCare with coaching team. Essentially what we found over the course of 60 months was that higher probability of retention. And you can see the annualized turnover by condition. And SafeCare with coaching was 14.9%, and the other conditions, 33, 37, 41%.

In this kind of setting, the workforce is critical when you think about what it takes to implement, to train providers, get them up to fidelity on an intervention, and then have them deliver the intervention where you have high rates of turnover. It’s a very tough issue. And it’s an issue that’s faced in almost every setting that I know of, whether it be with you know physicians providing telemedicine. Whether it be you know, bachelor’s level home visitors in this case, whether it be master’s level speech therapists, whatever. People move around, so the more we can keep trained professionals in the field, the better.

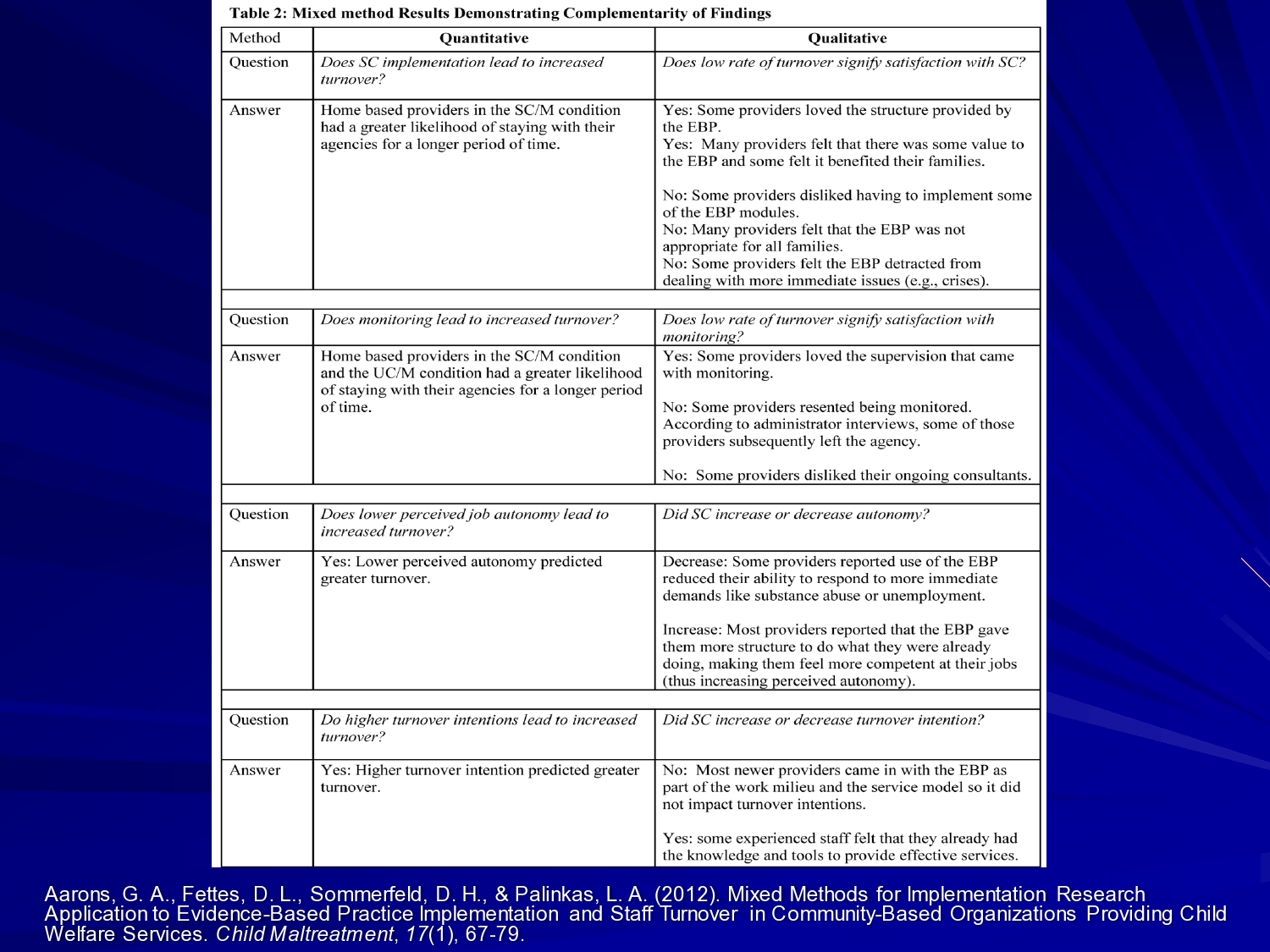

But we also wanted to know qualitatively what does this mean a little bit. So does the low rate of turnover signify satisfaction with SafeCare? And the answers from our qualitative analysis was yes some providers love the structure, many providers felt that there was some value to the EBP, and felt it benefit of their families, but some providers disliked having to implement some of the evidence-based practice modules. Some of them were harder than others. If you’re doing home health and your client is a nurse, and you have to go through those steps, that makes it uncomfortable interacting with your client. And some providers felt that SafeCare detracted from dealing with more immediate issues like the crises that tend to occur with these families.

So what we try to do is use our mixed methods to contextualize our quantitative findings here. Early in the study, we actually used quantitative measures of whether providers liked SafeCare or didn’t like SafeCare. Kind of their attitudes toward SafeCare once they had a little bit of experience to do maximum variation sampling for our qualitative interviews. So used a quantitative to inform our qualitative sampling approach. And we used the qualitative to inform our quantitative data collection.

We also looked at just the focus groups, and worked with the providers to understand the factors associated with SafeCare implementation for them. And you know the things that were critical were acceptability of SafeCare to the caseworker and to the family, appropriate to the needs of the family, the caseworker’s own motivations. So sometimes you find a shift newer caseworkers who were coming out of school, or coming into an internship may have liked the structure for example, that it provides in delivering casework. Their experiences with being trained. So having a brief more focal training where they can get out in the field and practice rather than a long protracted training period. And the extent of organizational support. So at the team level do their organizations and leaders really support the practice and support them in delivery of the practice. And the impact of SafeCare on the outcomes and the process of their case management.

So part of what SafeCare involves is checking off skills that the parents are learning. So it gives them a metric for seeing, are the parents getting better at interacting with their child? Are they getting better at providing a safe environment, a healthy environment for their child? So those aspects of the intervention might be something you’d want to look at in a study. Can we change the way we provide feedback to providers or to organizations around an intervention so that they understand their clients are improving, rather than just going on a sense that things are improving?

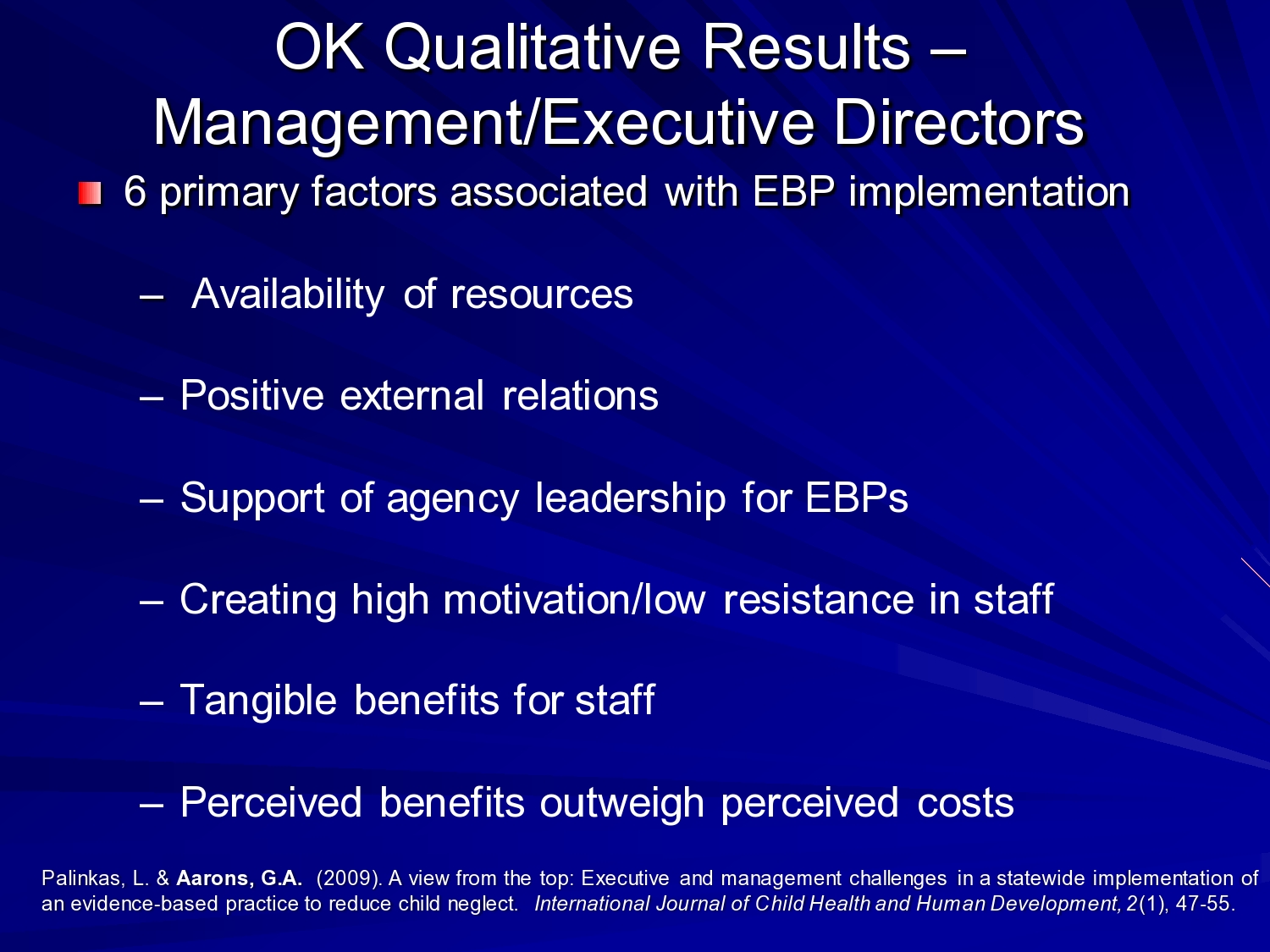

From our interviews with managers and executive directors, the factors that were important for them were availability of resources, both in their contracts with the state, but also extra resources for the families. You know switch covers for outlets in the home, doorknob covers, locks for cupboards where there may be toxic chemicals and things like that. And actually, you know, one of the interesting things I learned is that you know, it’s not so much toxic chemicals that are implicated in poisoning for kids, it’s things like strawberry flavored shampoo, or you know these kinds of things we may not consider putting up for kids, but those are really the more common sources of poisoning for kids. That’s an aside.

The managers and directors, their positive external relations both with the agencies, how they compete against one another, but how they also collaborate when need be in the system. The support of the top agency leadership for evidence-based practice. So having real buy-in and support from the top leadership that kind of filters down through the organization. Creating high motivation and low resistance in staff. So really trying to sell it to their providers, and tangible benefits for the staff themselves. You know, I’m learning a skill that makes me a better professional, I can be more effective with my families also, and we’ve seen this too, going back to the turnover issue sometimes when folks get credentialed it makes them more marketable. So that’s also a challenge.

And the perceived benefits of implementing the evidence-based practice outweigh the costs.

So you can see, you know a difference between when we look at the provider level, what’s important there, and the managers and exec director levels. And that has implications for how you might design an intervention to actually improve the context for implementation of evidence-based practice.

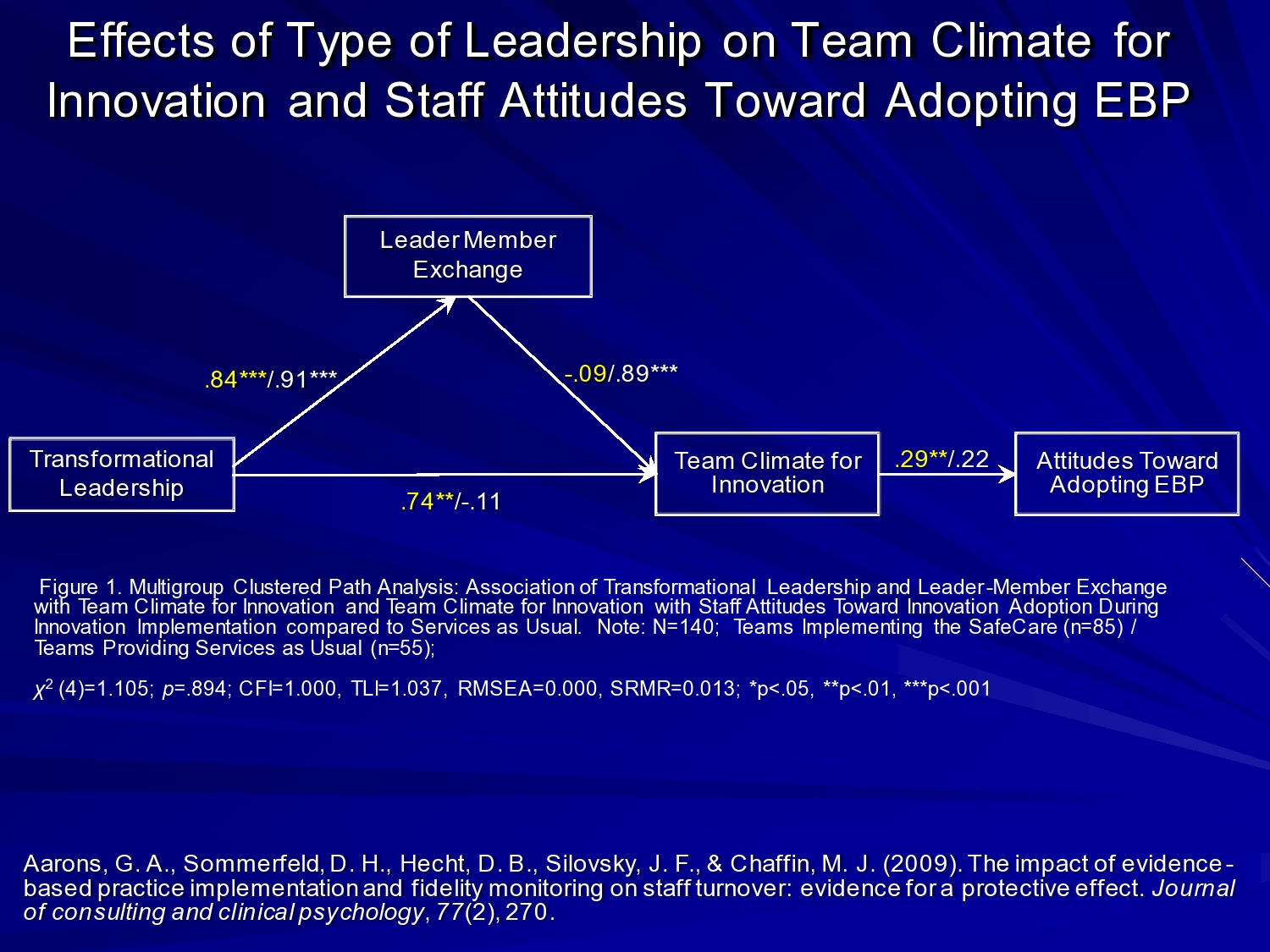

We also wanted to look at the issue of leadership, which is one of the areas that I’m interested in. And so we looked at the impact of transformational or charismatic leadership. And this really is comprised of things like you know individualized consideration. Do leaders — team leaders now we’re talking about for each of those 21 teams we saw — do team leaders pay attention to the individual needs of their staff. Can they intellectually stimulate their staff? Can they get them excited? Can they motivate them? Can they be inspirational in that process?

And what we found on the left in yellow are the teams implementing SafeCare. On the right was the services as usual, where you had strong transformational leader during implementation that created a more positive team climate for acceptance of innovation, and more positive attitudes towards adopting evidence-based practice.

One of the areas that I’m working now, also with developmental funding from NIMH, is we developed a leadership and organizational change intervention that we want to test more broadly to see if we can bolster this kind of leadership to create a positive climate and get better implementation and fidelity. Take it beyond just providers’ attitudes, but see if we can get better fidelity and outcomes where we have those multiple levels of support across an organization and team.

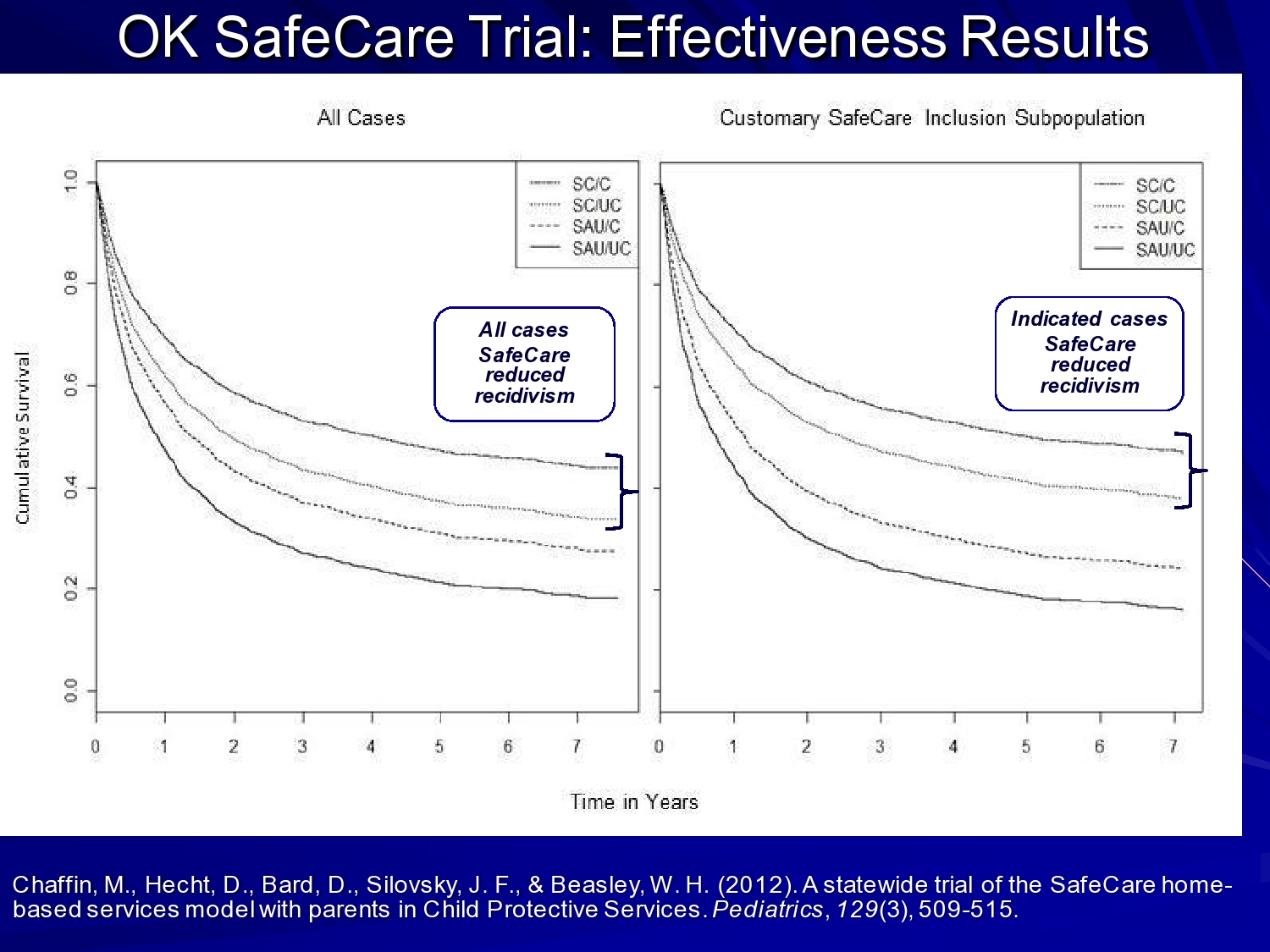

So this is the hybrid part of the study. So this is Mark Chaffin’s effectiveness data they published in Pediatrics. And he showed that recidivism, or re-reports for abuse and neglect were reduced for the population overall in the services. But for those indicated cases those families where neglect was really the primary issue, an even stronger effect. So, we’ve been looking at implementation issues, but as I said, we built it on top of an ongoing effectiveness trial, so we’re able to look at both, and now we’re able to combine data sets to look across the entire intervention.

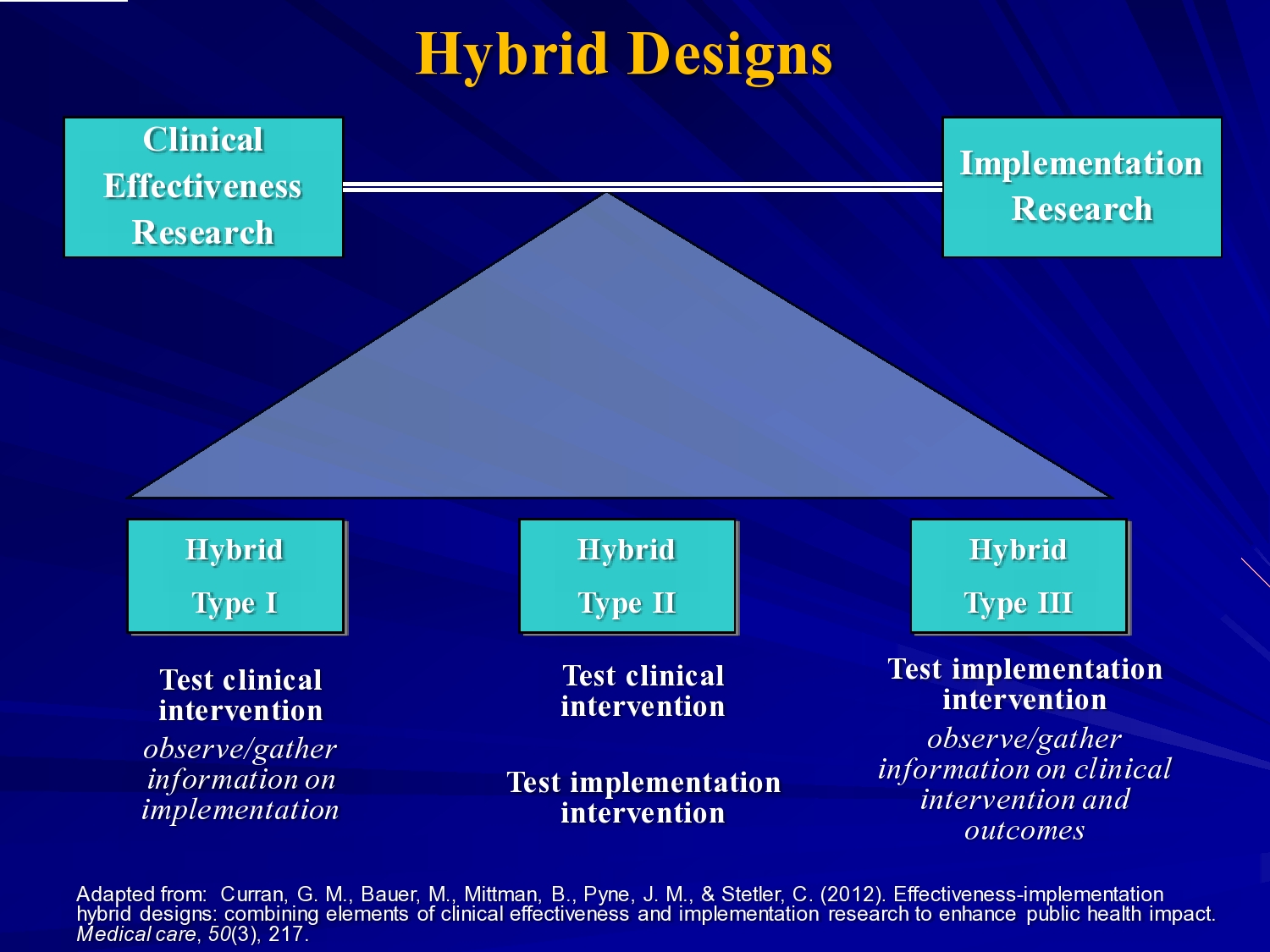

Hybrid Designs

That brings me more to hybrid designs in general. Geoffrey Curran and his colleagues talked about these hybrids type 1, type 2, type 3. I think what we’re seeing mostly is hybrid type 1 studies, where they’re looking at primarily effectiveness, but also looking at implementation factors along the way, more observational. But we are also seeing some type 2s, where you’re looking at both. Manipulating an intervention, and also testing out an implementation strategy.

The study I want to talk about is one Tom Patterson and I are working on. Tom is an HIV prevention researcher, and he developed an intervention to reduce HIV transmission from sex workers.

He developed this, and he did his efficacy trials in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez. And found good efficacy for the intervention. His intervention is a cognitive behavioral intervention where they train sex workers to negotiate safer sex with their client. So in these settings in Mexico, the understanding is that you’re not going to be able to eradicate it, but can we do a harm reduction approach.

We partnered with Mexfam, which is a large community based organization in Mexico and 13 sites of their women’s reproductive health clinics training their health workers to do outreach to sex workers now. Bring them in for testing, they’d also train them in this model with the goal of reducing STIs, and in particular HIV. So those are the sites we’re actually just wrapping up data collection in the last 3 sites.

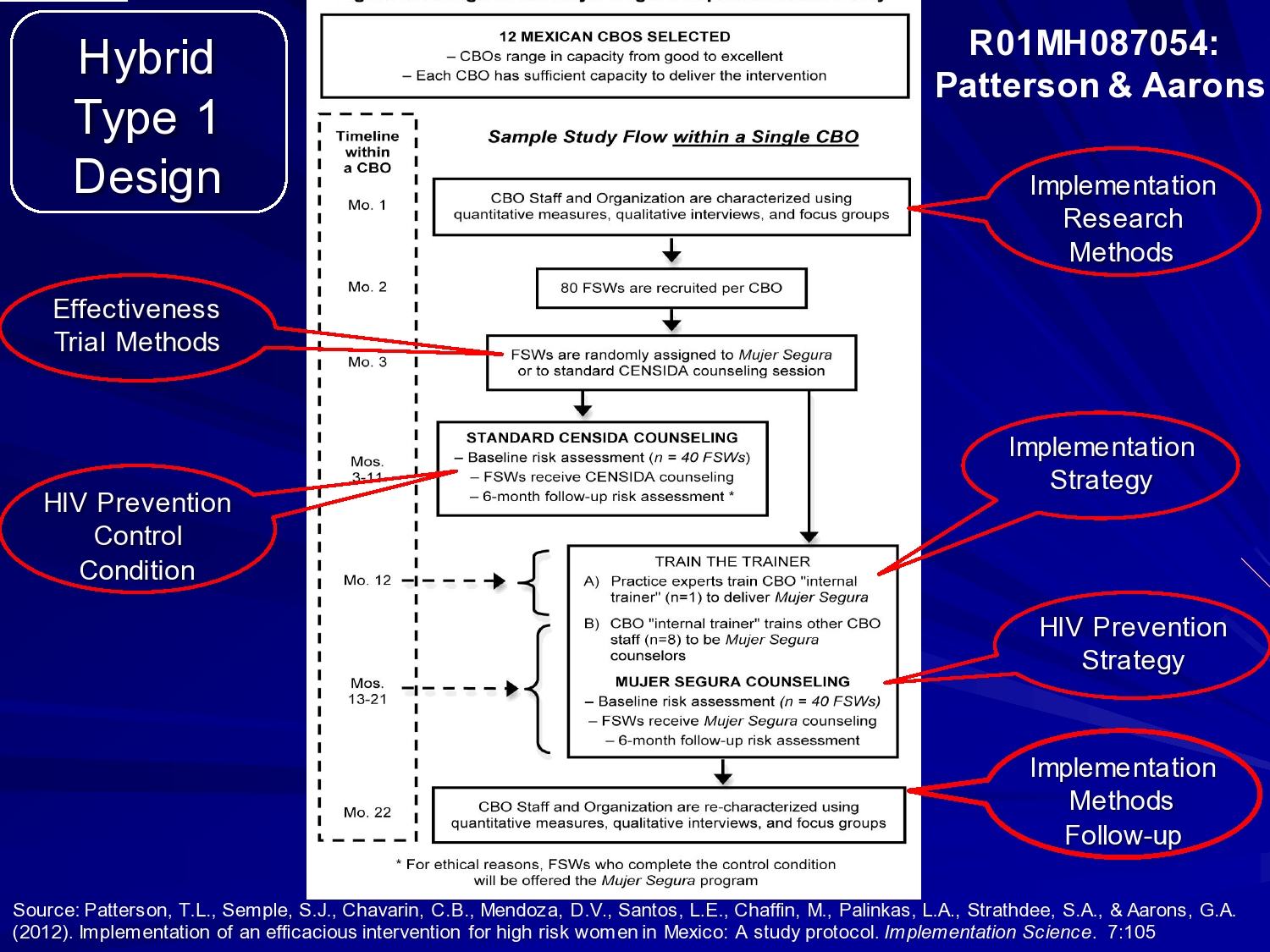

This is the study design, and this is the best way I could illustrate it. I tried to really highlight what were the effectiveness trial methods and what were the implementation research methods.

For implementation, we’re observing the implementation process and using a train-the-trainer model. So our Mexican physician goes to each site and trains a person at that site in the intervention. They then train staff in the agency, but that’s at all sites. So we’re looking at the process, but we’re not actually comparing that to a different implementation strategy.

The research methods are to do quantitative measures, and qualitative interviews, and focus groups at each clinic just prior to implementation, recruiting the sex workers, and then randomly assigning — this is the effectiveness trial — randomly assigning the sex workers to Segura, the healthy woman intervention, or a standard HIV counseling session.

The implementation strategy as I said, is train the trainer. The HIV prevention strategy is the Mujer Segura cognitive behavioral intervention. And then at the end of each site’s recruitment of the sex workers, then follow up over time, then we go back and do our implementation methods again at the end of the study.

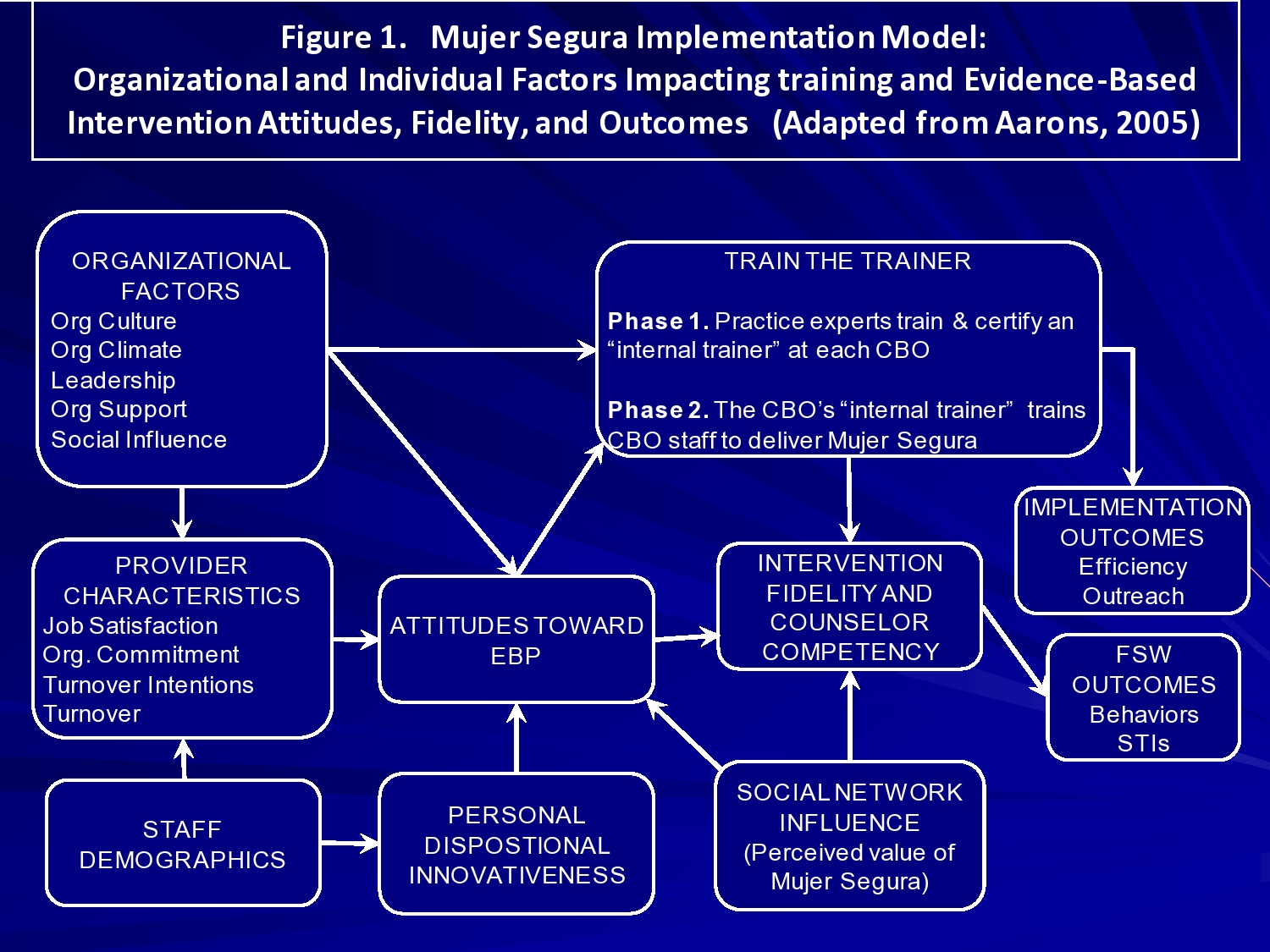

What we’re looking at in terms of the implementation framework is pulling again from a multilevel framework looking at organizational factors, the culture, climate, leadership, organizational support, and social influence at each clinic and their relationship to Mexfam Central and Mexico City. Also looking at provider characteristics such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, their turnover intentions, and turnover demographics. Their experience, their attitudes towards evidence-based practice. Their personal innovativeness, and the impacts of that on intervention fidelity, and counselor competency, and then outcomes. So we’ll be looking at that both with quantitative and qualitative measures as we get our data in. Okay so that’s that study.

Cascading Models

I want to talk briefly about some other models and questions. Cascading models typically address scale up issues: how do you take local expertise and move that into a community?

So, you may have different hypotheses in this type of study. You may be interested in equivalence rather than difference. When you have the highly trained providers, can they train another organization in the community, can they train yet another, and can you get equal levels of fidelity? So now the hypothesis shifts from a hypothesis difference testing to equivalence.

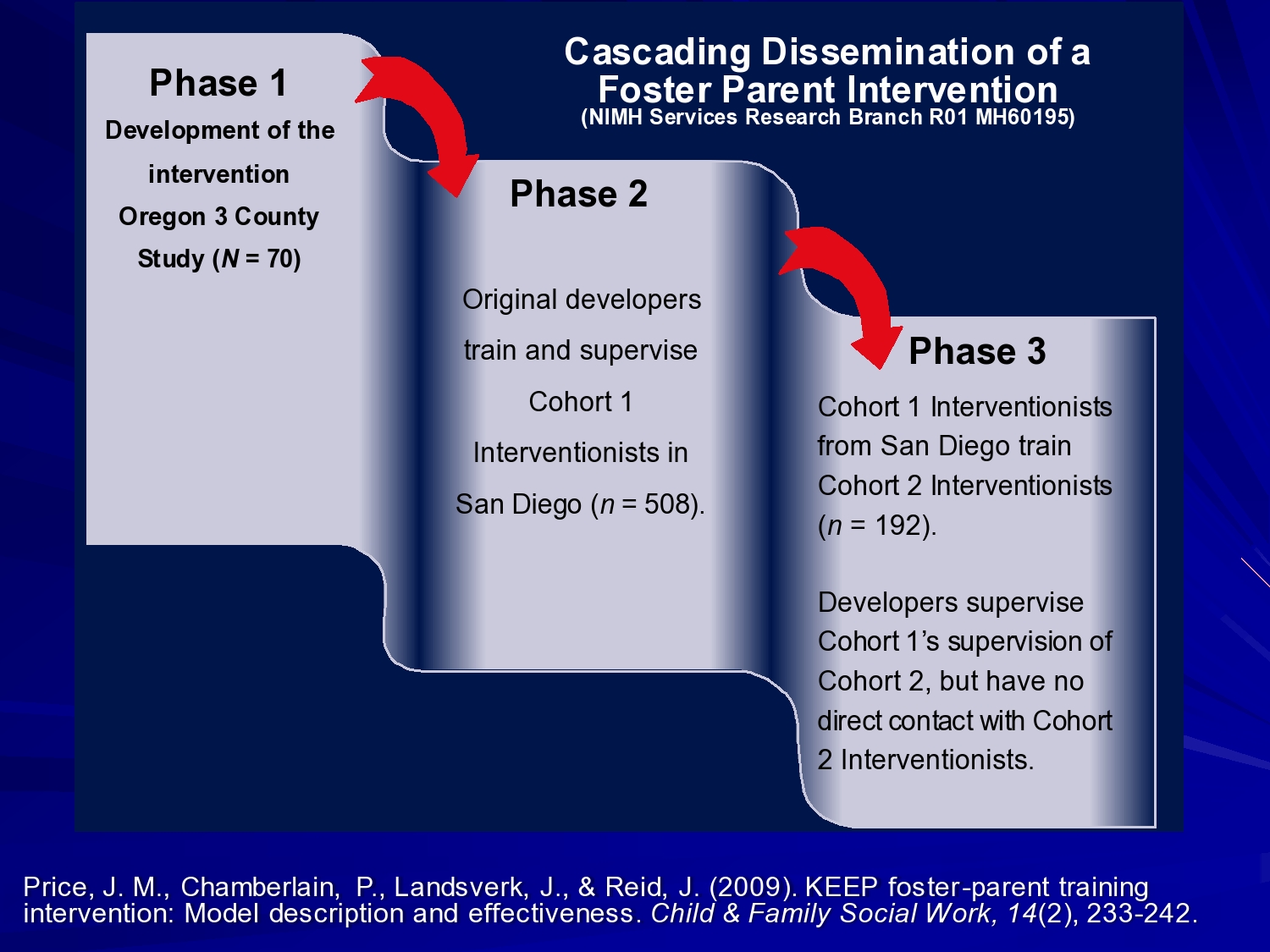

A nice example of this is Patty Chamberlain and Joe Price’s cascading dissemination of a foster parent intervention. This is multidimensional treatment foster care for kids with behavior problems in foster care. This was developed up at the Oregon Social Learning Center. Efficacy tested in 3 counties in Oregon.

In phase 2, the original developers trained and supervised intervention, this in San Diego. And in phase 3, those interventionists trained another cohort in San Diego.

So the idea is: Can you roll this out in a community and get good levels of fidelity? The answer is yes, if you do it right.

Baseline rates of behavior problems didn’t differ for phase 2 and phase 3. So you didn’t see worse problem. So essentially the intervention, even though it rolled out away from the developer was not ineffective.

No differences between rates of trial problems and treatment termination. Assignment was associated with significant decrease in child problems for baseline overall. So overall, the intervention was working. And no decrement in treatment effect when the intervention developers pulled back and had staff trained locally.

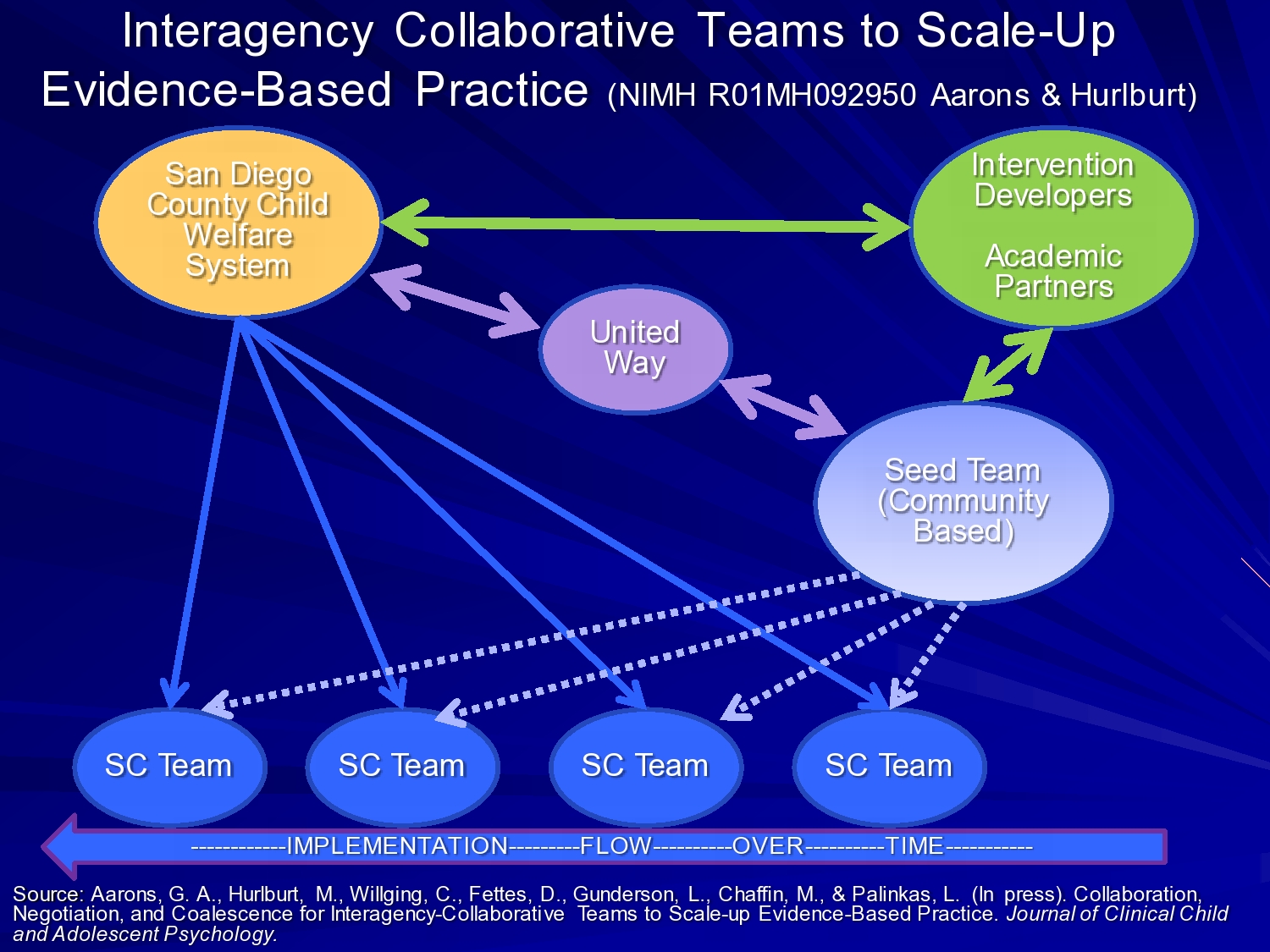

Another one that is in process right now is a study here in San Diego County called interagency collaborative teams to scale up evidence-based practice. And this again is a multilevel where the academic partners — myself and my colleagues and folks from OUHSC and SafeCare — work with San Diego County Child Welfare, the United Way as a funder of services.

The United Way, in this situation, decided that rather than giving $5,000 or $15,000 grants to print pamphlets and put those in pediatrician’s offices. We want to make wholesale system change. We want to try to impact an entire system. So United Way stepped up and provided training dollars for a few years to support building a seed team in the community. The intervention developers from Georgia State University trained the seed team to become certified trainers and coaches and then the seed team trains successive SafeCare teams across the county in the rollout.

And we’re just looking at initial fidelity data using a really interesting latent variable model that Mark Chaffin is doing, and showing just minor decrements in fidelity, but not significant decrements in fidelity over time as it rolls out.

The other unique feature of this study is the interagency nature. These teams are made up of providers from multiple organizations who work together on these treatment teams. So the idea is to spread the expertise across the contracting organizations for which they work.

And we used a metaphor analogy of a computed, distributed computing system in our proposal. So trying to think about that innovation criteria in our proposal. So what does this mean when we distribute expertise throughout a system? Can we do it effectively?

Additional Examples

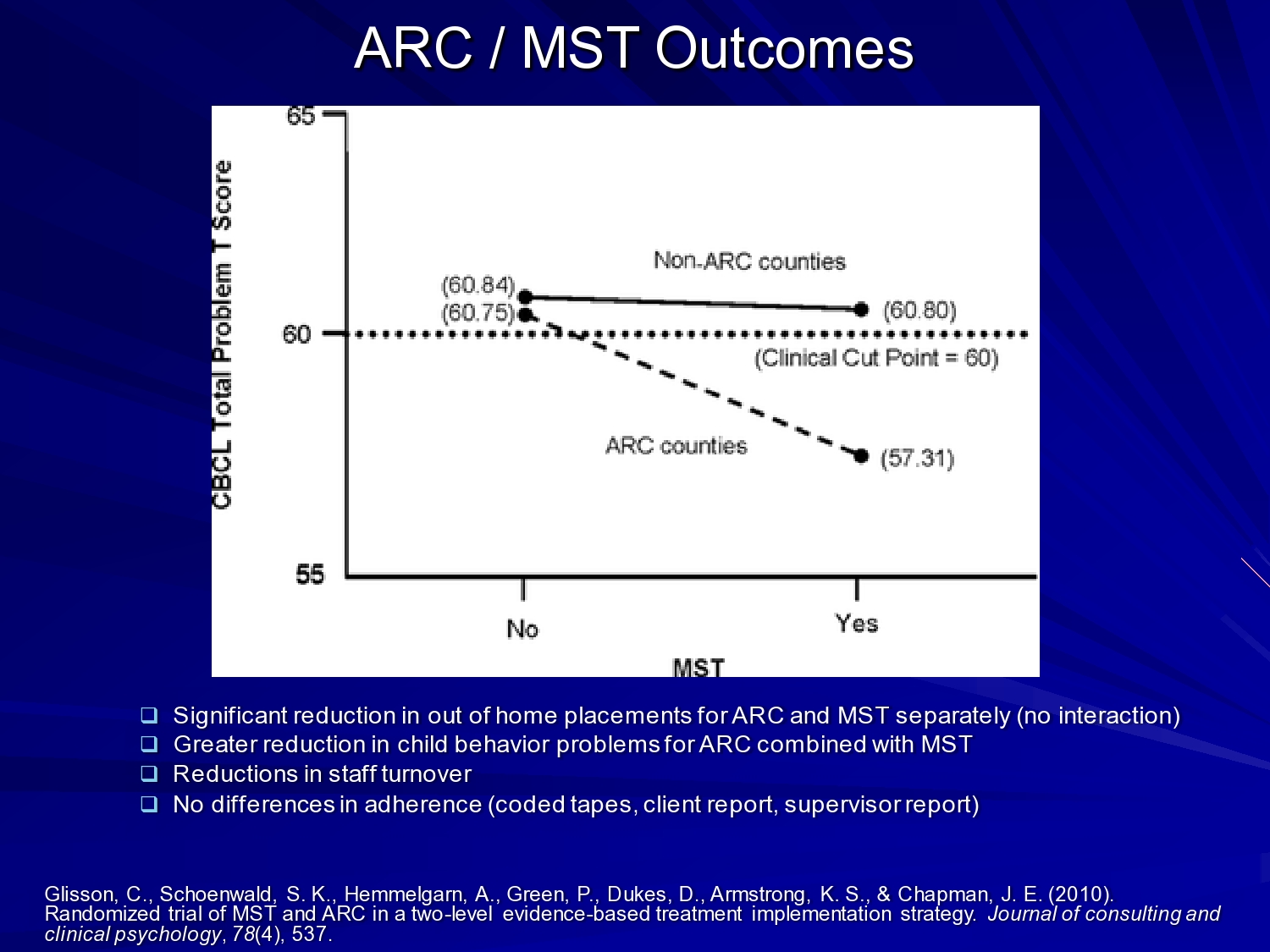

So I showed you Charles’ model. Just quickly talking about outcomes now. You know Charles Glisson’s intervention is really interesting because it focuses on improving the culture and climate of human service organizations. And as far as I know he’s one of the only people to demonstrate that if you improve worker satisfaction, organizational climate, and culture, you can get improved clinical outcomes, even if you don’t change the clinical intervention.

In his previous studies he did correlational studies, then a kind of proof of concept. And then this one, this is an implementation of multi-systemic therapy in a 2 x 2 design crossed with his ARC organizational intervention. And he was able to show you know significant reduction in out of home placements in behavior problems for ARC and multi-systemic therapy separately. So, both were having an effect, but having an effect on reduced child behavior problems in the ARC counties where MST was present. So really interesting study were you’re looking at those organizational issues and looking at the clinical issues and clinical intervention at the same time.

So the last study I want to talk about is just thinking about adaptation.

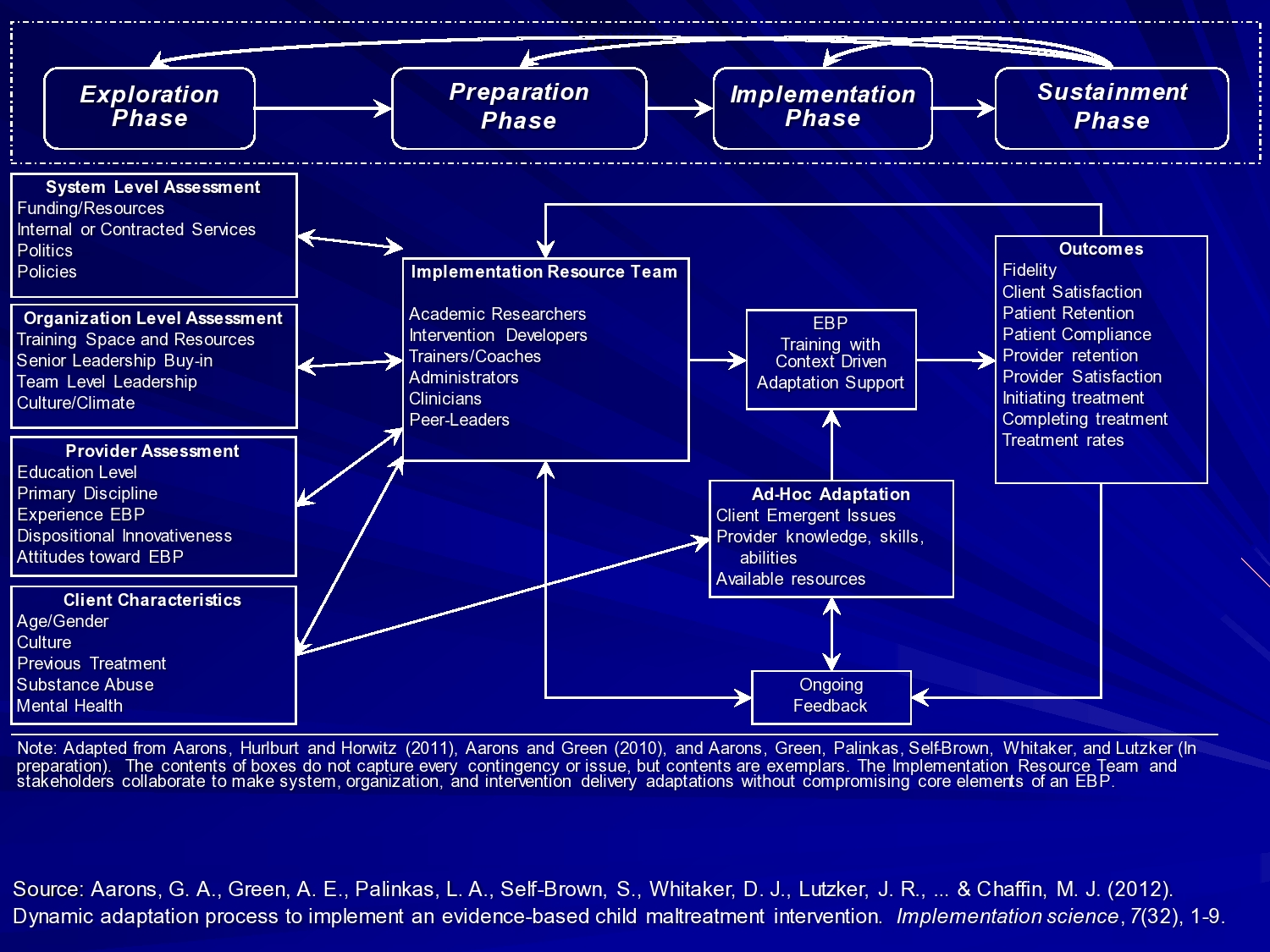

This is an integration of the EPIS framework with a process to really utilize it. So in the exploration phase, and this was funded by the CDC, what we developed was a system-level assessment, organization assessment, provider, and client to understand characteristics in the exploration phase. And it’s not just adapting an evidence-based practice, but it’s saying what do we adapt in organizations, what do we need to adapt in terms of the service system to help support this in the long run thinking about sustainment. And then convening what we call an implementation resource team that involves academic researchers, intervention developers, trainers, and coaches, administrator, clinicians, peer leaders through the preparation phase.

Once we start implementing then we build in some outcome assessment that we can feed back in the system. So in this case we use Web-enabled tablets with online system. So at the end of every session the home visitor hands the tablet to the client and it’s coded in the tablet, which module they’re working on, which session and they complete a very quick like 1-minute fidelity checklist. And that data comes back to our central system and we can feed that back both to the implementation resource team and to the ongoing coaches to provide feedback to the providers. So what we’re trying to do is to kind of create a system that works across these phases to really help support effective implementation.

So I think that’s a lot to think about. I could talk about other studies that I had ready in under resourced countries and task shifting studies, and a really interesting study in Nigeria using churches as a service delivery setting. Echezona Ezeanolue from University of Nevada is doing that study around reduction of maternal to child HIV transmission. So there’s lots of interesting studies that I think can inform how we think about applying your particular efficacy and effectiveness questions to an implementation framework. So I will just stop there. Thank you.

References

Aarons, G. A., Fettes, D. L., Sommerfeld, D. H. & Palinkas, L. A. (2012). Mixed methods for implementation research application to evidence-based practice implementation and staff turnover in community-based organizations providing child welfare services. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 67–79 [Article] [PubMed]

Aarons, G. A., Green, A. E., Palinkas, L. A., Self-Brown, S., Whitaker, D. J., Lutzker, J. R., Silovsky, J. F., Hecht, D. B. & Chaffin, M. J. (2012). Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implementation Science, 7(32), 1–9

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M. & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23 [Article] [PubMed]

Aarons, G. A., Fettes, D. L., Hurlburt, M. S., Palinkas, L. A., Gunderson, L., Willging, C. E. & Chaffin, M. J. (2014). Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(6), 915–928 [Article]

Aarons, G. A. & Palinkas, L. A. (2007). Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(4), 411–419 [Article] [PubMed]

Aarons, G. A., Sommerfeld, D. H., Hecht, D. B., Silovsky, J. F. & Chaffin, M. J. (2009). The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 270 [Article] [PubMed]

Aarons, G., Woodbridge, M. & Carmazzi, A. (2003). Examining leadership, organizational climate and service quality in a children’s system of care. The 15th Annual Research Conference Proceedings, a System of Care for Children’s Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base [Conference Proceedings] 15–18

Chaffin, M., Hecht, D., Bard, D., Silovsky, J. F. & Beasley, W. H. (2012). A statewide trial of the SafeCare home-based services model with parents in child protective services. Pediatrics, 129(3), 509–515 [Article] [PubMed]

Chamberlain, P., Price, J., Reid, J. & Landsverk, J. (2008). Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare, 87(5), 27 [PubMed]

Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M. & Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217 [Article] [PubMed]

Damschroder, L. J. Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A. & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50 [Article] [PubMed]

Ferlie, E. B. & Shortell, S. M. (2001). Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. The Milbank Quarterly, 79(2), 281 [Article] [PubMed]

Frambach, R. T. & Schillewaert, N. (2002). Organizational innovation adoption: A multi-level framework of determinants and opportunities for future research. Journal of Business Research, 55(2), 163–176 [Article]

Glisson, C. & Schoenwald, S. K. (2005). The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research, 7(4), 243–259 [Article] [PubMed]

Glisson, C., Schoenwald, S. K., Hemmelgarn, A., Green, P., Dukes, D., Armstrong, K. S. & Chapman, J. E. (2010). Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based treatment implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(4), 537 [Article] [PubMed]

Johnson, J. A., Knudsen, H. & Roman, P. (2002). Counselor turnover in private facilities. Frontlines: Linking Alcohol Services Research & Practice, 5(8),

Novins, D. K., Green, A. E., Legha, R. K. & Aarons, G. A. (2013). Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(10), 1009–1025 [Article]

Palinkas, L. A. & Aarons, G. A. (2009). A view from the top: Executive and management challenges in a statewide implementation of an evidence-based practice to reduce child neglect. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development, 2(1), 47–55

Patterson, T. L., Semple, S. J., Chavarin, C. V., Mendoza, D. V., Santos, L. E., Chaffin, M., Palinkas, L. A., Strathdee, S. A. & Aarons, G. A. (2012). Implementation of an efficacious intervention for high risk women in Mexico: Protocol for a multi-site randomized trial with a parallel study of organizational factors. Implementation Science, 7(1), 105 [Article] [PubMed]

Powell, B. J., Mcmillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Carpenter, C. R., Griffey, R. T., Bunger, A. C., Glass, J. E. & York, J. L. (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Review, 69(2), 123–157 [Article] [PubMed]

Price, J. M., Chamberlain, P., Landsverk, J. & Reid, J. (2009). KEEP foster‐parent training intervention: Model description and effectiveness. Child & Family Social Work, 14(2), 233–242 [Article]

Shortell, S. M. (2004). Increasing value: A research agenda for addressing the managerial and organizational challenges facing health care delivery in the United States. Medical Care Research and Review, 61(3 suppl), 12S–30S [Article] [PubMed]

Tabak, R. G., Khoong, E. C., Chambers, D. A. & Brownson, R. C. (2012). Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(3), 337–350 [Article] [PubMed]

Teddlie, C. & Tashakkori, A. (2003). Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research, 3–50