The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for length and clarity.

Overview of the Lidcombe Program

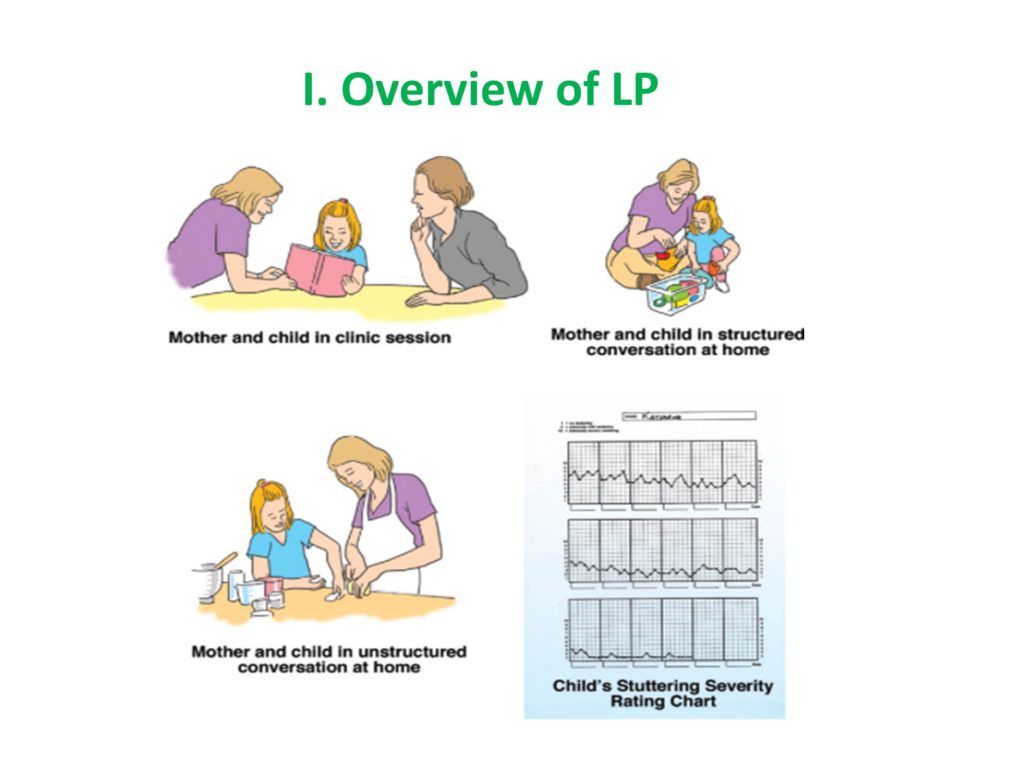

This is the flow chart of Lidcombe. It begins with a clinician meeting with a parent, and that goes on weekly or fortnightly, and the clinician’s job is to support the parent and teach the parent the program. The parent takes it home and works with the child in what are called structured conversations every day of the week, just 10 or 15 minutes to start out in these highly structured conversations which might be naming pictures or playing a game where the child had a short response.

Then it moves to unstructured situations like if the parent or caregiver is alone with the child, it works best rather than having other kids around, but it’s done in the car, in the grocery store, in other places. I think some of the magic is that the treatment is done where you want the generalization because these are preschool kids, so you want it at the home and you want it other places that the child is normally hanging out.

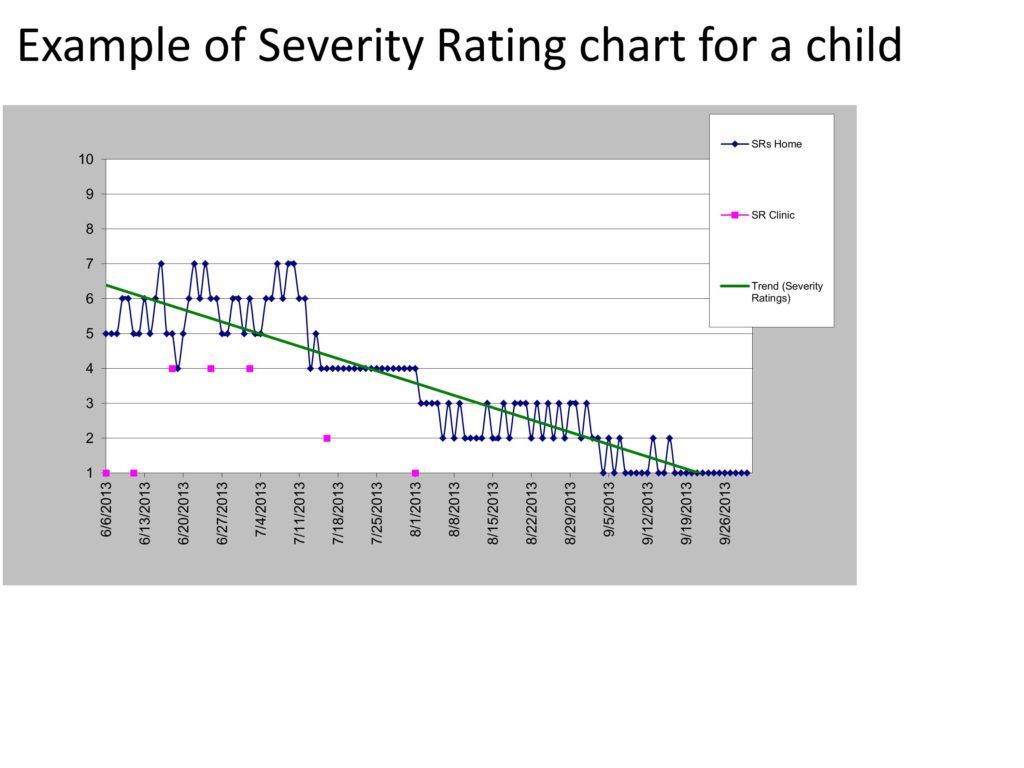

This last little icon is showing how progress is tracked both by the parents and by the clinicians, so I’ll show you an expanded version of this severity chart, but it seems to be an important element.

The engine behind this is verbal contingencies. At the beginning, there are structured conversations in which the parent and child are, let’s say looking over a picture book and the child is naming the pictures. Then, not very frequently, but like every five times a fluent utterance is praised, a stuttered utterance is — we usually call them a request for correction. I know in Western Australia they call them pick ups.

An example would be if the conversation is going on and the child stutters on a word like tr-tr-tr-tr- truck. The parent, in the most upbeat way, says, “Could you say truck again?” and the child most often will say it fluently, and the parent says, “That’s great! That was really smooth.” So the praises need to be varied because they need to be reinforcing. So, “That was really smooth talking.” “Great talking.” “That was wonderful.” The model that the clinician gives the parent is a very sort of upbeat model, and we’ll talk about the fact that this whole thing is fun for the child.

I asterisked the verbal contingencies because it’s got to be adaptable for the particular family you’re working with and the culture. It was developed in a Sydney suburb called Bankstown which was a very immigrant-rich environment. People were coming from all sorts of cultures. I’m sure you’ve experienced this. But you go to Europe or some other country and people are puzzled with your praises. The Australians were giving me examples with people from Arab cultures, where all they were willing to do is do a thumbs up or nod or a wink or something like that or some other signal for “say that again.” So I just want to emphasize that the flexibility within the core principles is a very important element of the Lidcombe Program.

I might say that this element of working with the child and actually saying something about the stuttering is one of the sticky points. It may be why it’s had difficulty being accepted in the United States because in the 1950s, some of you may know, there was a researcher-clinician named Wendell Johnson, who had a diagnosogenic theory that one of the things that causes stuttering is when a parent inappropriately thinks normal disfluencies are stuttering and calls attention to them or has some facial expression that disapproves of them, then stuttering starts. So there is a fear the Lidcombe Program will make stuttering worse. You’ll see in some of the studies I’m going to talk about an effort to show this was really not the case motivated some of the work.

There are weekly or fortnightly clinic sessions where the clinician asks the parent to demonstrate what they’re doing at home with the treatment. When the parent is demonstrating the treatment, you’re seeing is there fidelity in what is going on at home with what you’re hoping is going on at home.

So you also have these Severity Ratings that are done. This scale was developed by the Australians and shown to be valid and reliable for clinicians to teach to the parents to use for the daily ratings. 1 means typical fluency for that child’s age, 10 means the worst stuttering that a parent could imagine their child having. It’s funny that it never seems to be a big issue. Most kids start out between 5 and 7 in terms of the severity. But the clinician is always checking on the agreement between what they think the child’s rating might be — usually at the beginning of the session you have a period of about five or ten minutes in which you are recording the child and making an online judgment about the fluency and when that’s over and the child is still in the room you say — the clinician says to the parent, “What number would you put on that? What number would you give for the Severity Rating Scale?” Then the clinician says, “Well I would give it this.” And if there is more than one number difference in the Severity Rating Scale, then the clinician works with the parent to get them on the same page, as it were.

There are two stages of Lidcombe treatment. The first stage usually takes about 15 sessions, goes until the child is essentially stutter free, and the criterion for stutter free is three weeks in a row in which of those each seven-day week the Severity Ratings are 2 or below, and at least four of those seven days are 1s. And that’s gotta be three in a row. So it gives you the sense of there being stable fluency.

Stage 2 is, I don’t know why but the Lidcombe developers really didn’t like to call it a maintenance stage, but that’s what I call it — but it’s fading. It’s fading of the number of sessions. You have the session every two weeks. Then you begin to fade that so it’s every four weeks, then eight weeks, sixteen weeks. At the same time the parent is fading the amount of praise and pick ups that they are doing, so the child begins to maintain the fluency without that. In those first three weeks is when you’re most likely to get the relapse. So, parents will decide to come in more regularly or — Because it’s parent delivered, the parents feel they are having this beneficial effect. It’s not like, “I’ve got to go back to this clinician.” Actually most of the time we hear from parents that their child relapsed last week, but they knew just what to do. And because stuttering runs in families, if the first child is treated with Lidcombe and the second child starts to stutter, sometimes we don’t even hear about it until later when the parent has just figured out how they are going to deal with the situation.

Development of the Lidcombe Program Through Clinical Research

So let me go back to the history of the development of Lidcombe. Essentially, in the ’60s and ’70s, clinicians started using operant conditioning through verbal and non-verbal contingencies to reduce stuttering. A lot of that was single-subject design and it was coming out of the Kansas model.

But in the University of Minnesota, Dick Martin, Sam Haroldson, and people like that were doing a lot of studies, including the famous puppet study that came out in ’72, in which they had three or four single-subject design experiments where the kids were watching a puppet show, and when the kids stuttered, the puppet show would go dark and it would stay dark for several seconds and then it would come back on. Some of the kids would actually say, “Hey Susie Bell goes dark whenever I stutter.” Or something like that. These kids were followed up and it was found it was quite effective.

So Roger Ingham, who is an Australian, was doing a postdoc in Minnesota at the time and got quite interested in the methodology. His student, Mark Onslow, who is at the Lidcombe hospital tried the puppet show idea, and that didn’t seem to work. So he tried a few things.

They did experiments and refinements that they didn’t publish. But they learned that the program has to be highly supportive. So if you think about the puppet example, it’s just punishment. But they realized that praise was really important. That’s probably obvious to us all now.

It’s not only the verbal contingencies, but the whole deal has to be a lot of fun for the child. In other words, it can’t be too serious, it can’t be too glum. It’s play-based, so the kid’s got to be looking forward to it. And that ratio of positive to pick ups is high. And the SRs, the continuous assessments seem to be important. But I’ll show one study that maybe wasn’t so sure.

In any case the initial research was efficacy studies. At first there were three non-randomized phase II trials. Then there were two phase III randomized controlled trials.

So the Jones et al. study was in New Zealand because they wanted to get a country where it wasn’t as widely used. I don’t know why, but when we lived in Australia it was amazing, but one person would get a Sony VCR, and everybody in Australia would get the exact same thing. You know, pairs of pants or a kind of surfboard, it just spread like wildfire. So I think maybe that’s why Lidcombe was easily adopted in Australia.

Tina Latterman came over to Montreal and she studied with us for a while, as well. She’s from Germany, and her PhD dissertation which was a randomized control of Lidcombe in her native Germany. Tina found some resistance where German parents didn’t think play was a good idea. Education needs to be drill work and very serious. Also, the German parents objected to the use of plastic toys. They thought only wooden toys should be used, and that was what Tina had learned Lidcombe with. She was able to make adaptations and work quite successfully. I think it’s quite widely used in Germany.

So Jones et al. did a follow up — a 3-5 year follow up of the kids who had been in that first RCT, and they found their fluency had stuck.

There’s so much objection to the idea of punishment. A well-known center in Europe just were writing all sorts of negative reviews of Lidcombe even though they weren’t using it. They were going, “This makes the child feel terrible about their stuttering. How could you do this?” So research was done to show that Lidcombe is safe. That’s often where you start trials of a new drug or something. So Woods, Shearsby and those folks did a study when they used the Achenbach child behavior checklist. There’s a Q- something that begins with “q” like q-something. It’s an attachment scale. They showed not only was there no disruption in the parent-child bonding, but also the child was feeling much better about himself and so Lidcombe was having a benign effect. Which of course, you wouldn’t be surprised at that if it fixed the child’s stuttering.

Harrison et al. started to do some early dismantling studies. Liz Harrison was responding to the feeling that, “Do you really have to do anything with the stuttered speech? Couldn’t we just leave that out?” And she was able to show in this study that if you left that out, it would take longer and you wouldn’t get as good outcomes.

So let me just make sure I hit everything there. I actually think this is one of the most important studies that I’ll be talking about. Sue O’Brian published last year, with the Australian stuttering research crew, a study that showed it’s almost as effective when used by community clinicians. What they found — they compared, they looked at outcomes nine months after. Nine months was chosen because that’s what the RCT studies had done. So they wanted to compare these community SLPs’ outcomes with what the RCTs had shown you can expect after nine months. This was a good article because they talk about their fidelity checks, then they quote a number of different people on what is really important to consider in implementation studies.

Then the Lidcombe folks did a study of delivery by telehealth. As you can imagine, it started out by the telephone, and progressed to Skype. This latest study by Skype was RCT with 49 kids all within a relatively circumscribed area. Some of them randomly got a webcam, some of them randomly got face-to-face. They were absolutely equal in the amount of time it took and what the outcomes were. By the end of it, when the parents who were face-to-face found out the other parents had gotten a webcam — 2/3 of them wanted that. They would prefer that, because they didn’t have to come in to the clinic.

Additional research (Koushik, 2010) has shown that you may not have to see the parents every week.

Quickly, I’ll go over our research. We looked at our first 15 kids two years after they had gotten fluent and found that our results — when this was done by grad students — were at least as good as the Australians. And that pre-treatment severity, rather than frequency which the Australians say, predicts outcome.

Then we have a study that’s under review right now. It’s really the first study to show that girls do better than boys, which is not surprising. I think there’s this confluence or joining of natural recovery factors and the fact that girls just respond better to treatment.

And we’re trying to dismantle Lidcombe also. There has been some suggestion that it makes kids more fluent because their language is less. So a couple of our students — I thought I’d mention their names, Hannah and Elissa — a couple of our students have shown that the language of kids who have been going through Lidcombe doesn’t change any more than the language of controls who we’re just measuring for the same amount of time. They also looked at what they called parent conversational pressure, in terms of parent MLU, type/token ratio, and when the parent utters a statement that requires a response. So that didn’t change over the course of Lidcombe. Then Danra has done some work showing that fortnightly treatment is more effective than weekly treatment in terms of efficiency — fewer sessions are required.

The last slide is that we’re about to get our act together to do some implementation work looking at the EEE (Early Essential Education) SLPs in Vermont who deal with ages 3-5.

Some of the challenges we think we’re going to face include arranging the initial training so they are not only doing Lidcombe, but so we can also get them on board with feeling as part of a team in which they will be gathering data and we’ll all be working together. Then what has been mentioned several times and that is providing support — follow up support by people going out to their place, doing a listserv. Also, how do we standardize data collection; and what are the scheduling difficulties that they’ll have in their environment?