The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

I was asked to help frame some of the most important questions in implementation research. And I approached this not so much from study questions, but also questions that I think a field should be addressing as it begins to move toward implementation science.

I will also talk about important concepts and measures, and then talk a little bit about some data sources for implementation research.

What is our repertoire of evidence-based practices?

The first question is: “What’s our repertoire of evidence-based treatments or programs that are ready and suitable for implementation?” And yesterday my colleague, Matt, said, “Not everything that’s evidence-based should be implemented.” And I think we all know, unfortunately, that we have systems of care where programs that are not evidence-based are well entrenched, and continue to be delivered.

I’ve been interested to hear from your wonderful questions and the discussions we had yesterday about the progress in your field of developing evidence-based treatments, and evidence-based programs. So take stock and think about whether they are ready for dissemination.

Now, fields vary, and although I view myself as an implementation researcher at this point, I would not say that every field has the right balance of whether it should be emphasizing implementation, or continuing to develop new evidence for the programs and treatments. And those are not either/or — every field needs to emphasize both. Certainly as researchers we know and hope that there will be new evidence in the future.

So I’m not in any way saying that we should stop the pipeline about evidence testing, evidence development, or effectiveness testing. But you might ask yourself, “Are there some areas that we don’t have good evidence yet?” If so, then I would caution you to emphasize continuing to strengthen what you know about those programs.

But when we have effective interventions, certainly it’s time to deliver them.

The latest research shows we really should do something with all of this research. Several of us work in the area of mental health, and we are sobered by the fact that about 10% of people with serious mental disorder receive evidence-based care. So certainly we’re not done improving treatments, we’re not done developing programs, but we have a ratio that needs to emphasize the rollout, the delivery, and the implementation of what we do know.

What is the implementation gap?

Then a very important question is asking how big is the implementation gap? What is the quality of service that we are delivering? To what extent are we providing, and to what extent are the individual’s families and communities we work with receiving evidence-based care?

I cited that dreadful 10% level in mental health. What is it in your field? Do you know that? Do you know the proportion the people receiving speech, language, or hearing treatment that are receiving the best care, that are receiving evidence-based care?

There’s a way to calculate this. It gets us to that very challenging concept in our research, the denominator. So we need to know how many people are receiving services as the denominator; in the numerator, how many are getting evidence-based programs and treatments.

And then if we want to be even more ambitious and take on a public health perspective, our denominator becomes even more challenging. We don’t look just at the people receiving care, but at the people who need services. So what percent of that group is receiving evidence- based care?

Are there studies in your field that calculate this? And here we get at some of the infrastructure problems in research; particularly troubling in social work, and from some of my conversations with you yesterday I think also troubling in your field. We have to have procedure codes. And we have to have them readily available. Either we have to go out and ask people in kind of epi-studies, or we need to be able to look in some database and see some indication of the service that was provided, and those procedure codes need to be nuanced, and sensitive, and specific enough that we can tell one program from another, not just that they got our services. So this sounds like this is an important question for your field, and I would encourage you that this is a really important area to start an implementation research agenda.

What is the implementation context?

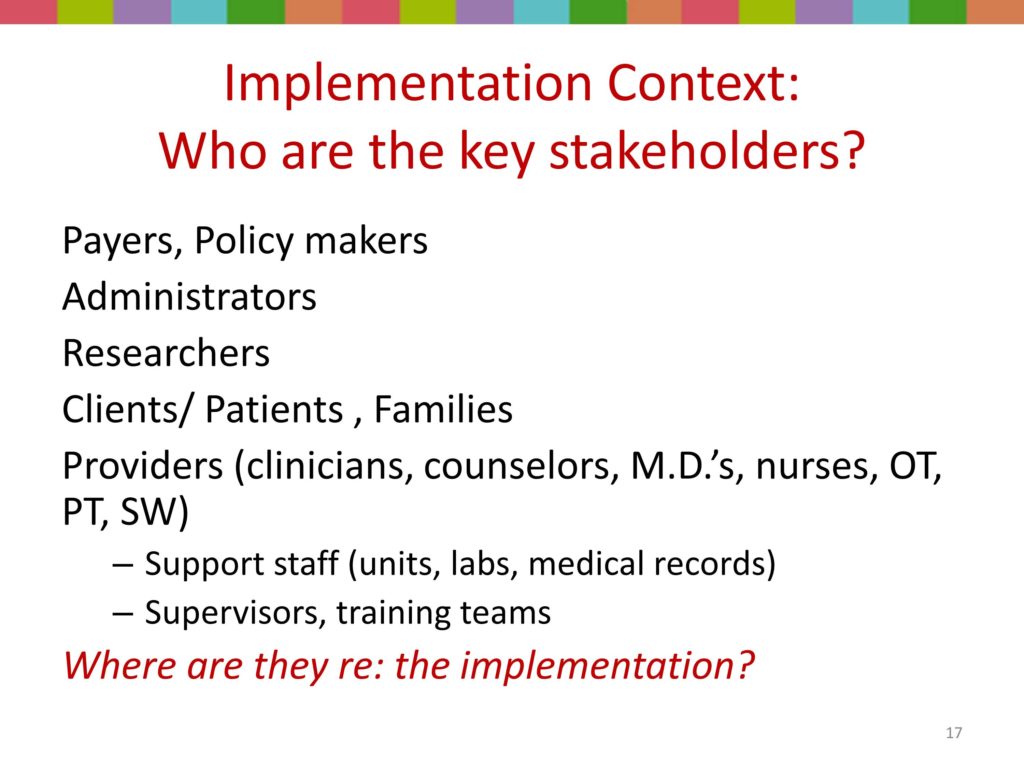

Now, another really important question is, “What is the implementation context?” And we got at this yesterday. Somebody asked a really good question, “Okay; I’m delivering services and somebody is improving, but insurance says services have to stop.” So we talked about how the policy, the payment environment is sometimes out of whack with delivering quality or evidence-based services.

There are a lot of issues about context that I’m going to spend a little bit of time talking with you about: who are the key stakeholders, who and what are the policy and practice drivers. Greg set the stage for helping us think about readiness for change, organizational climate, and of particular importance, a settings’ implementation history — what are the prior and current barriers and facilitators?

I think one mistake implementation researchers often make is that when we’re going to get on our horse and go out and implement something, we think we’re the first game in town. But you know what, people have already implemented something; they have a history with implementation.

They may not have a history of participating in implementation research, but they have adopted something, they’re holding onto certain things, and they’ve also changed, although we may think that the change we’re bringing them is the newest sliced bread. But there is a history, and it’s very shortsighted of implementers or implementation researchers to ignore or not capture that. I’m going to come back to the issue of context in a little bit.

What implementation strategies/processes are effective?

Another question, “What implementation strategies and processes are effective?” And this is really the area of implementation research that mobilizes me most at this particular moment in time. And there’s a reason for that. I still remember the day that the strategies question was put to me. And it led to I think my very first conversation with David Chambers.

At our School of Social Work in the year 2000 — much to my surprise because I was not on the curriculum committee, I had been working to strengthen the evidence-based for social work practice. But I’ll never forget the May faculty meeting when the curriculum committee brought to our faculty a proposal that our school deliberately offer an evidence-based curriculum.

Somebody said, “But I’ll have to shut down my course because there’s not evidence-based intervention in this area.” We said, “No, no; that’s not what it means. It means we’re going to be transparent about the extent of evidence. We’re going to say, ‘There’s a lot of practice wisdom behind this. There’s a lot of support for this, but here’s the extent of what we know about research supporting this’.”

So thereafter we tried to engage the stakeholders in our school community, a very important component of whom are our field instructors, because social workers have practicum. We use agencies as educational training grounds, and we try to work really hard to be sure that what we do in the classroom is aligned with what’s happening in the field. So we knew that we had to take the very next step and engage field educators, our practicum instructors, our agency sites, and our conversation and our commitment to evidence-based social work training.

A very astute field instructor said, “Okay. I think this is really important. I get it. But tell me, what are the evidence-based strategies for me, an agency director, to increase my agency’s delivery of evidence-based services?”

So David Chambers had just joined the National Institute of Mental Health, and he and I began a conversation. I wanted to ask, “Here’s where we are in our school; here’s where I am in my quest for implementation research. I really want to know, what do we know about strategy?” His short answer was, “We don’t have the answer to that question quite yet.”

So we’ve embarked on a whole set of efforts, this whole front row where colleagues we really enjoy working together in trying to build capacity around this. So we’re still asking the field instructor’s question: “What implementation strategies and processes are most effective?”

How do we support settings’ capacity to implement multiple evidence-based approaches?

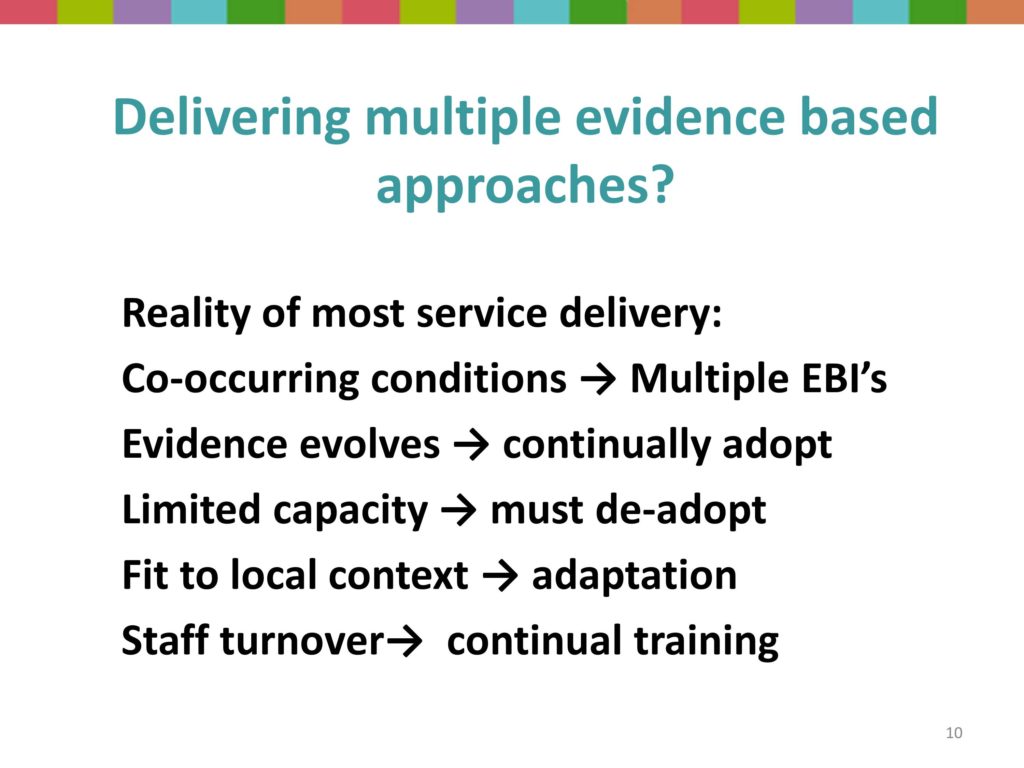

Then, of course, how do we support settings’ capacity? This is a question we’re just now beginning to tackle in the field. And this is a big hairy complex issue.

It’s also a function of researchers’ myopic views that agencies are interested in one new treatment, my treatment; you know, the program that I’m developing. So I want to take this treatment to this agency and say, “I have discovered something really great.” Well, guess what, you know, they’ve — the people they serve, the people that your profession serves, they have multiple problems. And until we get to a really specialized model of service delivery in our fields, where somebody does one intervention, and then we’ll have a problem of leaving our patients and clients behind, because they have multiple problems.

So most organizations face the very challenging task of delivering multiple interventions, most of which they want to be high-quality and evidence-based. But they also have to face with the fact that something new is going to be evident tomorrow, or in two years; and that they have limited — what we call “absorptive capacity,”. They can’t just endlessly take on more and more evidence-based practices, something has to get voted off the island, something has to get de-adopted.

Then of course there’s the challenge of fitting interventions to local contexts. And staff turnover means that a lot of that infrastructure or capacity building that they do walks. And so there’s a continuous process.

So the reality of agencies in striving to deliver multiple evidence-based interventions is this notion of it’s not new for them, it’s not the first time they’ve thought about adopting something, nor are they single-issue voters. They’ve got a lot going on.

How do we scale up and sustain evidence-based service?

Treatment evidence continues to grow.

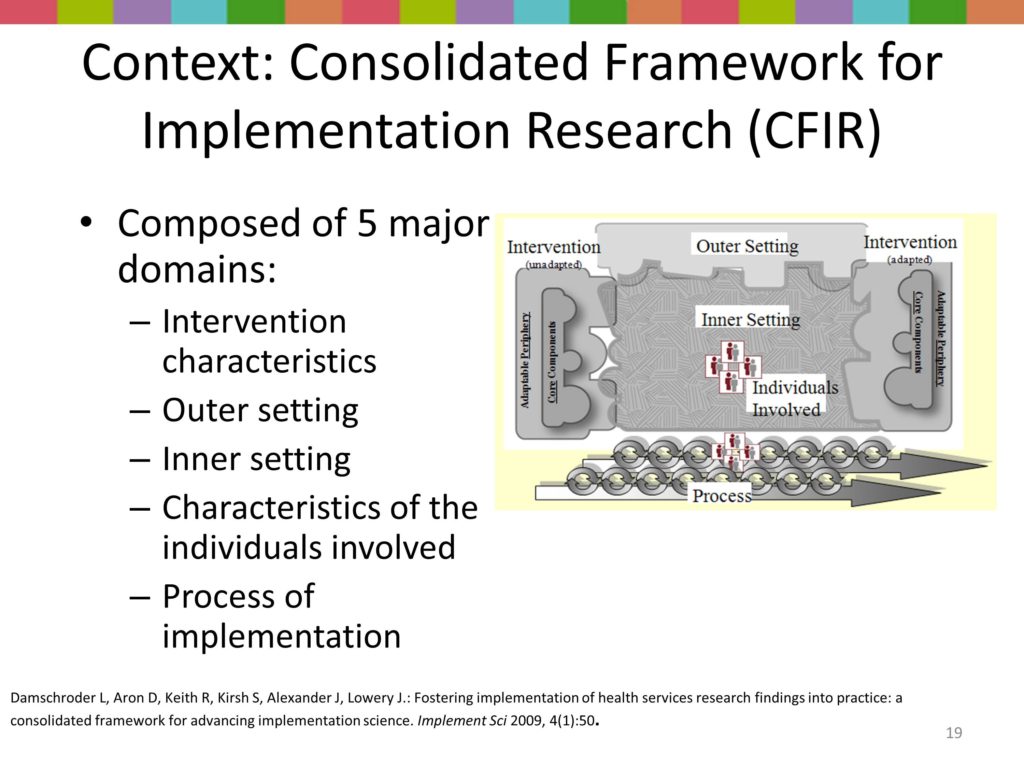

Key Construct: Implementation Context

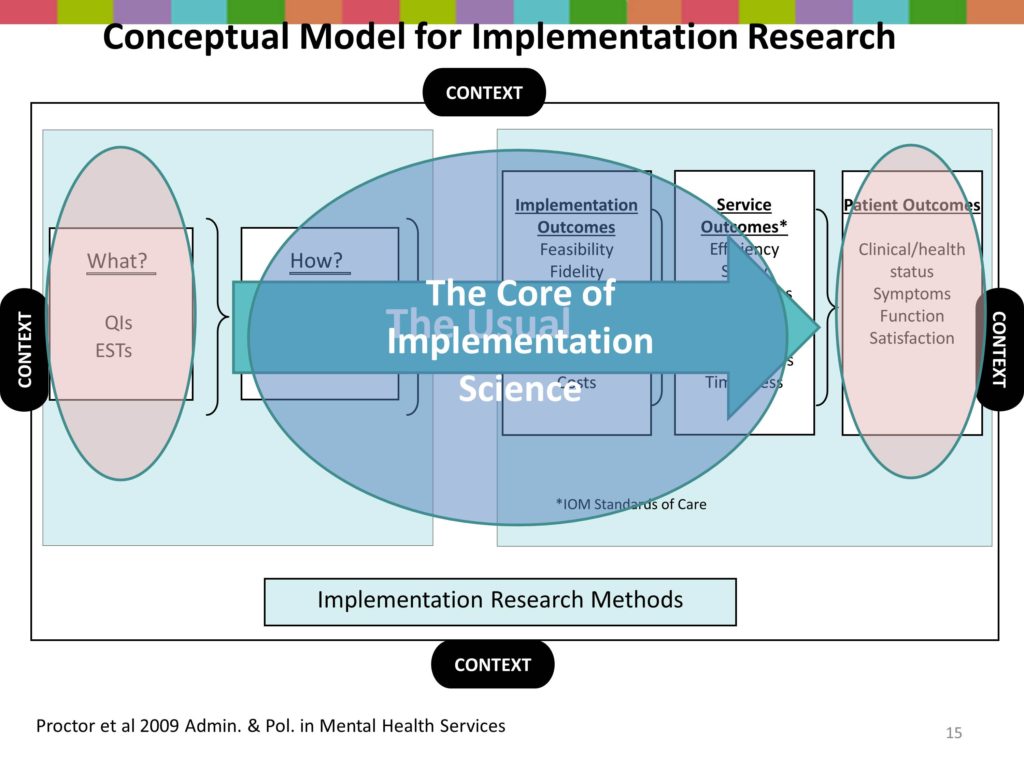

So around implementation context — we all have our models so here’s my model. Actually, this model was developed by our faculty team in the Implementation Research Institute. I know that David and Larry and going to plug TIDIRH, but the faculty team when we were preparing to launch our first NIH supported training program said, “We’ve got to figure out what’s important. So together we developed this framework.

With treatment efficacy and effectiveness research we’re very familiar with what’s on the far left hand here. That is an evidence-based treatment, or that is a program. And it produces patient outcomes. So that’s business as usual. We test an intervention for clinical outcomes.

But in implementation research, we have some new ingredients. We have, first of all, the how. Those are processes or strategies, the implementation strategies. It’s in the same box here with the what because both of those are professional activities, they’re programs, they’re interventions, they require that we do something.

We also have a couple of other boxes of outcomes. The middle box are service system outcomes, that the IOM has said all health professionals better start paying attention to. These are things like the efficiency, the safety.

I think we’ve all had a family member who’s gone in for surgery, and they write with a marker on the part of the body that’s going to be operated on that says, “Operate here,” so that we don’t get the wrong knee replaced. So that concept of safety we grasp it, you know, how important that is. I work with anesthesiologists who talk about how important it is to make sure that the patient not wake up during surgery, and I thought, “Oh my –” I didn’t even think of that as a possibility. But so there are a lot of safety issues that we’re all over when it comes to physical medicine. But there are safety issues in our fields too.

There are issues of equity, disparities, patient centeredness, and timeliness. And I worry a lot about timeliness in social work and mental health in that people wait a long time before they come for help. I know that’s true in your field too. Stigma, thinking why I ought to be able to manage this, this keeps people from coming quickly. And we are not very timely in the delivery of evidence-based or newly developed programs.

So in addition to business as usual — testing an intervention for a patient outcome, the IOM says let’s look at systems of care. And we had a great session yesterday on health services research.

There also are unique outcomes in implementation, and I’m going to talk about those in a few minutes, and why it’s important that we have distinct implementation outcomes. So the heart then of implementation research is looking at this area, the implementation strategies, the service system outcomes, and the implementation outcomes.

Now, hybrid designs have meant it’s not either/or. But I think my talk and a couple other talks later it may help you to know that we are talking about a different kind of research.

So then the context — all of that was surrounded by context. So that’s the first construct that I want to help unpack this morning.

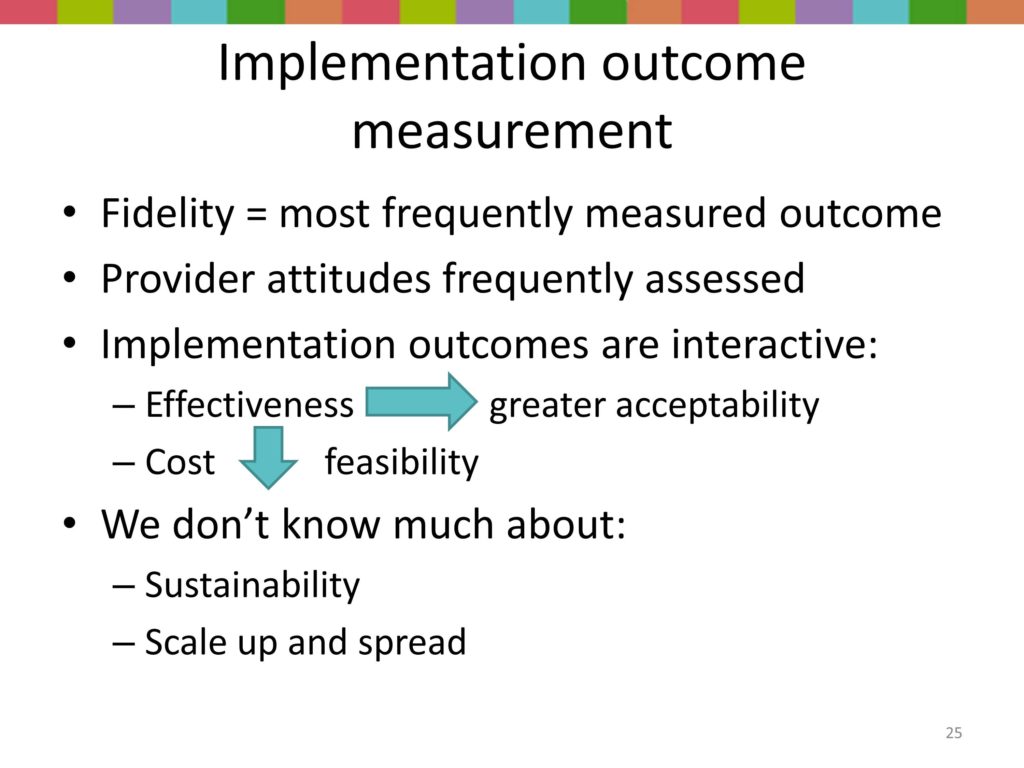

Key Construct: Implementation Outcomes

Key Construct: Implementation Strategies

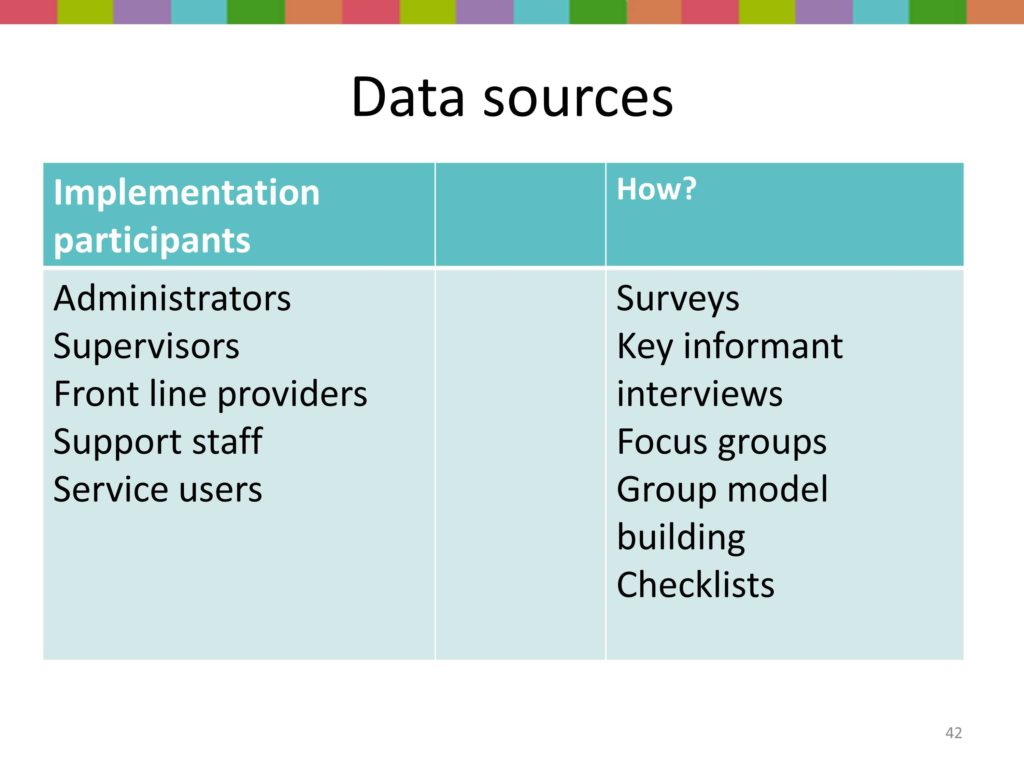

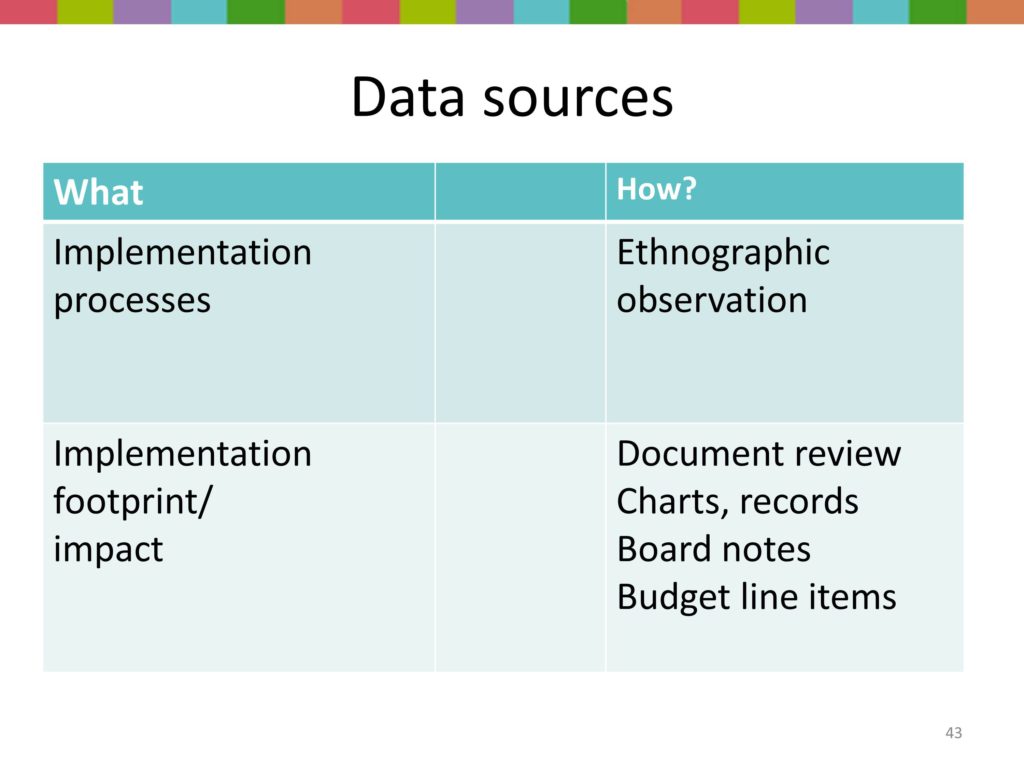

Data Sources