The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Introduction

I’m either blessed or cursed — I counted up the other day that I’ve done 12 population level trials and that’s a lot. I have a lot of skinned knees and I have some hard won lessons learned that I’d like to impart with you very briefly in the course of about 45 minutes.

I’m going to talk about some fundamental units of behavioral change. I’m very interested in finding small things that make a difference because the truth is its only small things that make a difference. Otherwise, nothing would be happening in the world, because big things are ridiculously hard to do. Just try to implement national healthcare in the United States as an example.

I got interested in this because of my studies at the University of Kansas. I was very, very fortunate that Don Beyer was my dissertation advisor and Todd Risley and Montrose Wolf were on my committee along with Jim Sherman and John Wright because I was also interested in media, which is how I became involved in a very large project with Sesame Street to test a way to prevent pedestrian accidents to young children which was the third leading cause of death in the United States. Can you imagine you’re looking for a dissertation topic that no one has ever done an experimental study that was successful in, and that’s a big deal. And the prior experimental study resulted in more children dying. So one of the first things to remember if you’re going to do anything large is that you have the possibility of harm and you need to measure adverse effects. I never do a study without trying to measure for the possibility of adverse effects. Don’t believe that you’re going to cure cancer without killing a few people as a possibility, so you got to do that.

So, I’m going to talk about a testable approach for improving speech language and hearing outcomes at a population level. My very earliest work in graduate school was in the infant development laboratory where Frances Degen Horowitz and her students did all of that work that showed that babies were smart. The doctors didn’t think so, but we saw the babies and they were.

Building a “Carbon Valley”

We, however, are carbon-based and we run on carbon, each other.

Now, what we have to do is begin to create a Periodic Table. From the Periodic Table, if you’re a chemist or an engineer or something you can create an amazing array of things but you actually know the properties of each one of those components, how they work in the world and then we begin to learn how to put them together to make something that’s completely novel that has never happened before in the universe.

That’s a pretty cool thing, but we need to think about that also in the context of speech, language and hearing. What are the fundamental units that we’re manipulating? Do we have a science for fundamental units?

I mean I think back of Todd Risley’s study and Betty Hart’s study of the meaningful differences. That is the most amazing study in the world. Micro-coding of all of those interactions in the PD-11 computer that that was done on was on the reverse side of my office, and I could hear that damn thing operate all of the time. We had a 10 megabyte hard drive that was the size of a telephone booth. That was a big deal and it happened.

So I am arguing today for creating that Periodic Table for our work, simplicity.

Now, the Meaningful Differences study has 1,485 citations. Does anyone here have an article that’s got 1,400 citations? You know, that puts you in a world class level, okay. That’s pretty damn good. One of the most influential studies, yet we have failed to convert that into a population level practice to make meaningful differences at a large scale to improve the speech, hearing, and language of young children.

Charlie Greenwood has developed a little app. I think it works now on, or could potentially work on a phone and it can code the same kinds of things that we had all of those observers that went out in the meaningful differences study, but we’ve not used that particularly. For example there could be an app that was giving feedback to families about their meaningful differences in language composition; that’s a possibility to use silicon to change carbon lifeforms.

Creating Nurturing Environments

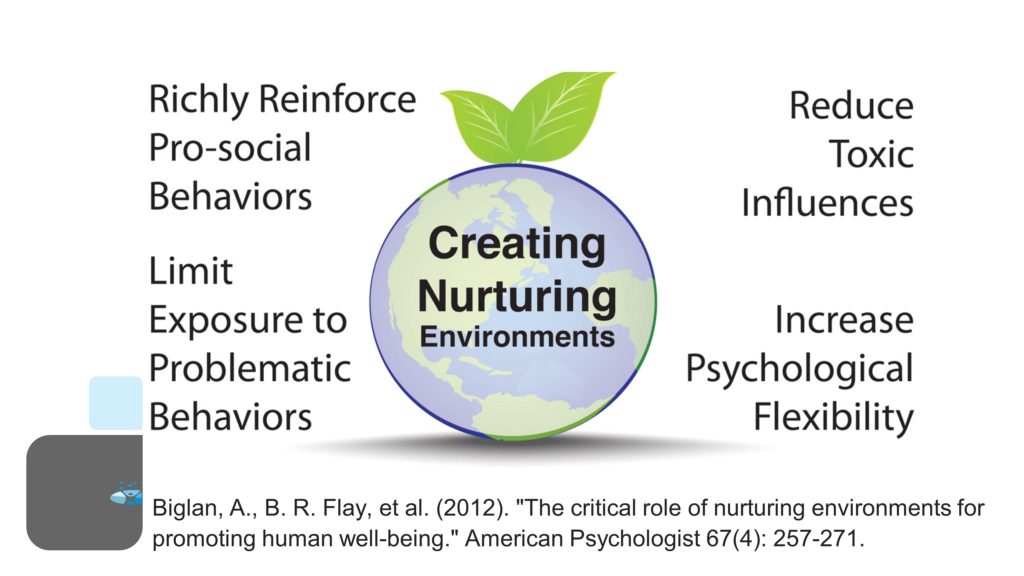

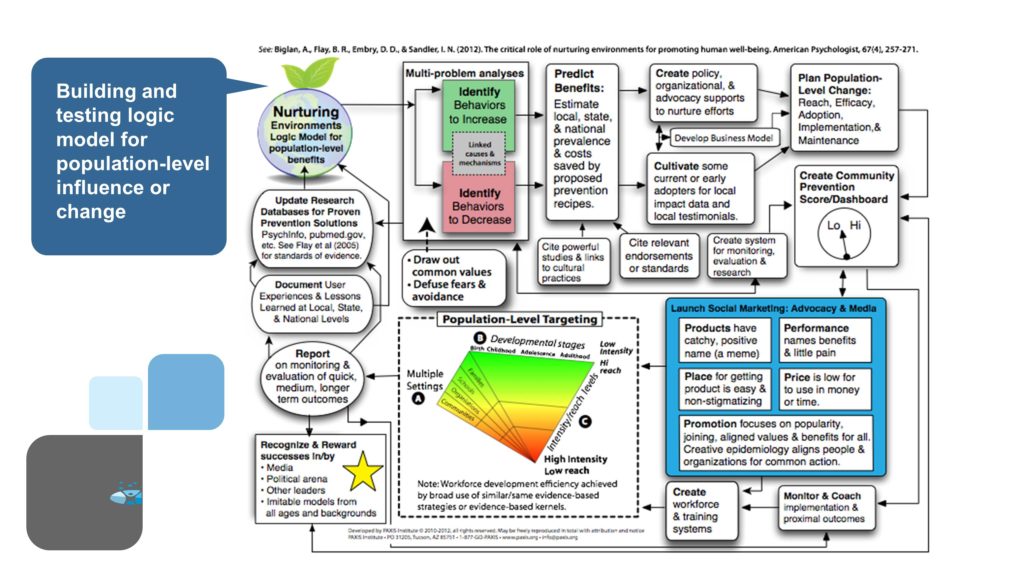

So, Tony Biglan and I and Brian Flay and Irwin Sandler have a paper published in the American Psychologist called “The Critical Role of Nurturing Environments in Human Development” and that was one of those life bucket list things to get, you know, it’s an article in the American Psychologist and I knew it was coming out and just one day I went out to my mailbox and opened it up, “Oh there’s, and oh my God! It’s the first article, wow! Score one Dennis.” So, we proposed that there are four things that are categorical to help us frame what we might need to do to make changes.

One is to create a nurturing environment and does language and speech and hearing acquisition require a nurturing environment? What did we learn from the meaningful differences study? Hell yes it requires a nurturing environment and it’s a huge effect from very tiny things. So for instance their study shows that the kids who are doing well are richly reinforced for positive behavior and their language acquisitions.

We have to limit exposure to problematic behavior. Rob over here is involved in a lot of that, in trying to reduce problematic behavior in schools. Because we know that that problematic behavior is basically contagious. The other reason we know that it’s contagious is, what is the principle predator of humans since the invention of stone tools? Other humans. And what is the principle source of safety for said humans since the invention of stone tools? Other humans with other stone tools. So understand the evolutionary dynamics that we are operating in human systems. Humans are the only species that are both eusocial and predatory of each other at the same time. That’s a very interesting complexity.

So limiting the exposure to problematic behavior. In meaningful differences we see that by the issue of folks all of the negative imperative, “Stop that, don’t do that,” those kinds of things that have sort of catastrophic effects on children’s development in increasing oppositional defiance and conduct disorders. And by the way, most mental, emotional and behavioral disorders are not disorders. They are evolutionary adaptations to when human society goes nuts. That’s an important thing to remember.

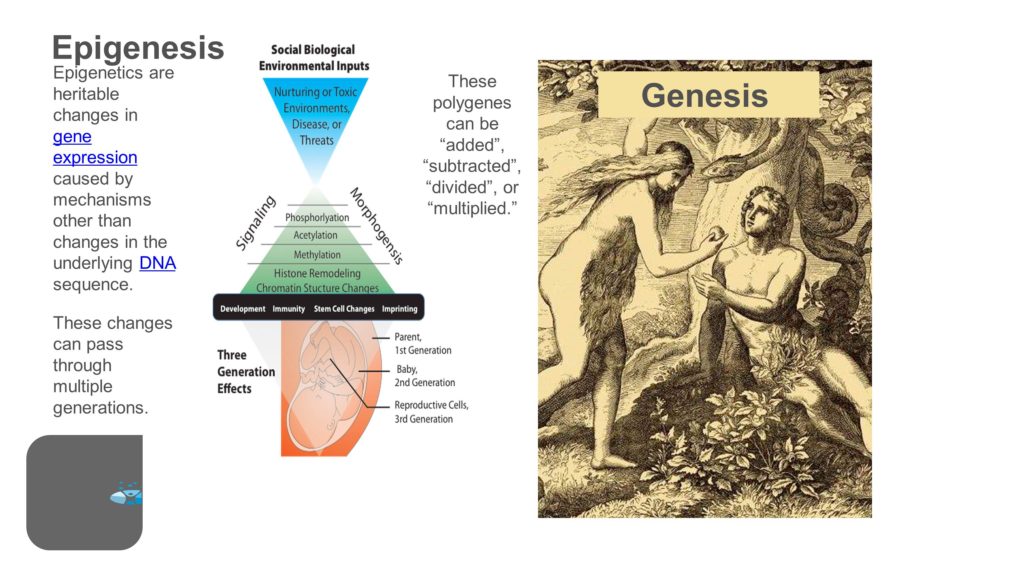

And now reduce toxic influences. Toxic influences can be social and they can be biological. One of the things is a lot of us were trained in behavior analysis and, you know, we were not supposed to touch those physiological things. Which is like, “Those are bad, don’t talk about those things.” You can’t do that! You can’t ignore a whole branch of science! So now we’re interested, for example, in what are some of the causes of the rising levels of mental, emotional and behavioral disorders which include learning disabilities.

For instance, has anyone noticed that we’ve had a major dietary shift in America? Okay. You may or may not know that one of the most significant dietary shifts that account for mental, emotional and behavioral disorders is the change in the omega-6 and omega-3 ratio in consumption even during pregnancy. So, if a woman consumes low-levels of omega-3 fatty acid during pregnancy i.e., fish, oily fish, she will likely — 32% of those woman’s children by age 8 will have development disorders, 32%. Now, if they eat oily fish only 15% will have developmental disorders by age 8. That’s in a huge study, the ALSPAC Study in the United Kingdom funded by the National Institutes of Health. So we have to pay attention to those kinds of things, and I want you understand the physiology of omega-6 and omega-3, it’s linkages, how it affects human behavior, the acquisition of behavior, the reinforcement system all of those things begin to make sense and then when you look at it in the evolutionary and anthropological context you begin to understand why some of those things were selected by humans.

For instance one of the things we know that autism; is autism spectrum disorder increasing in this country? Yes. It appears to be. I mean the first time people started talking about I only had one kid with autism spectrum disorder at the University of Kansas, and we got all those kids across the state because we were the sort of tertiary place. I only had one. Well, I learned for example that vitamin D deficiency helps predict the rise in autism spectrum disorder, which varies by latitude, and varies by skin color and diet. There’s a whole bunch of very interesting things can vary in there.

We also have to increase psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility, this is the work, of Steven Hayes his really great work on relational frame theory. Now, I do recommend that if you try to read that book, put it beside your bed side because if you suffer from insomnia it will cure it without any adverse effects. It’s very heavy reading but important. Psychological flexibility is necessary for us to adopt and use new practices, for us to be able to open ourselves up to a new theoretical construct. Just because I was trained in behavioral analysis doesn’t mean that I should be blind to anthropological things or findings in medicine. I better be smart about these things.

Evidence-Based Kernels

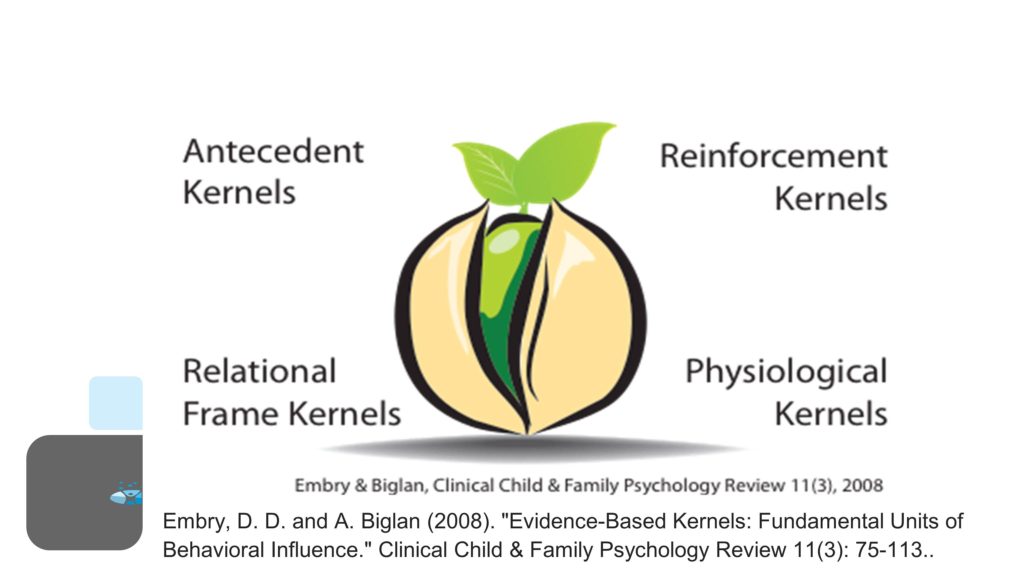

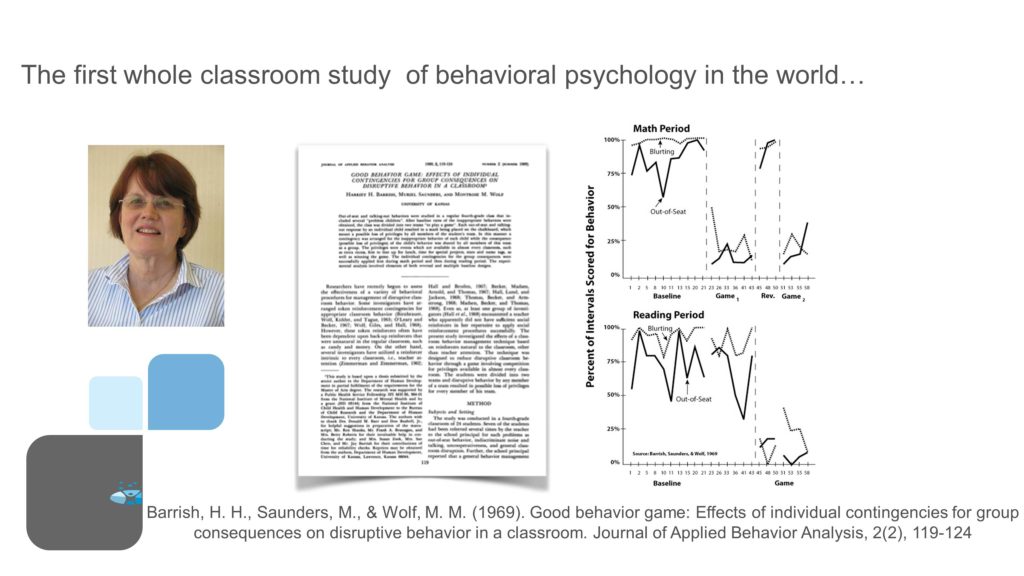

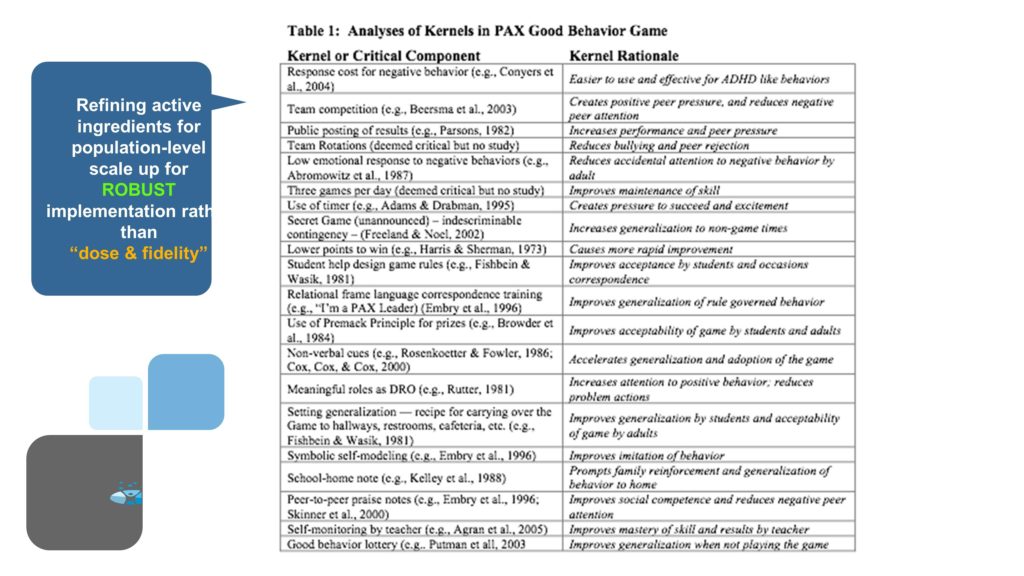

Now, Tony and I wrote a paper in 2008 called “Evidence-based Kernels; Fundamental Units of Behavioral Influence” because I’d written several papers before. I had gotten in an argument with Rico Catalano. We were arguing with this thing Tony had set up, and I was saying that you know when I get a medicine it has the label on it for the active ingredients. In our prevention science and treatment science and intervention science we ought to be listing the active ingredients and the inert ingredients cause there’s a lot of inert stuff in things. And Rico said, no, no, no because people will start to roll their own, and I said that’s a good idea. It was California.

So, we started arguing, and then one of the things I asked him — they were doing a comprehensive school reform study, and so were we, and I asked him, I said “What’s the first thing you teach teachers?” You know, what’s the first practical thing after you get done with the theory? “Oh, we teach them a universal signal for quiet, and we have them put up the peace sign and they use a chime or a bell or something like that.” And I said, “Ha, that’s funny we use the same thing except a harmonica.” “Why do you do that?” “Well, if you can’t get the children’s attention and change transition times it doesn’t matter what all the rest of the stuff is. You do this properly, you get approximately 144 more hours for meaningful responding in the classroom and teaching.” So, thinking about kernels came out of that.

Antecedent kernels would be one of them, relational frame kernels. For example for those of you who are familiar with our work in Peacebuilders, we gave the kids what’s called an I AM Manual, an I am statement: I am a peacebuilder; I praise people; I give up putdowns; I seek wise people as advisers and friends; I notice and speak up about hurts; I right/wrongs; I offer help; I promise to build peace at home and school and community each day. Very powerful when you have that kind of relational frame of identity because people start to reinforce it in each other. And then physiological kernels we’ve talked about.

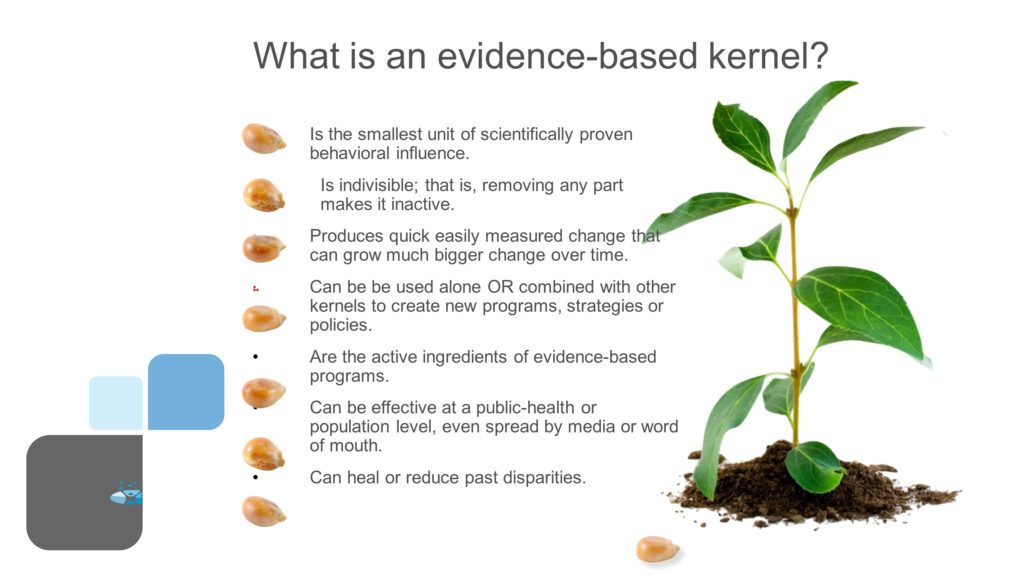

An evidence-base kernel is the smallest scientifically proven unit of behavioral influence. It’s indivisible. If I take away that harmonica, it doesn’t work nearly as well. If I take away the lanyard, it doesn’t work as well because I’ll be leaving the harmonica over there and I’m here, so I lose time. The lanyard make sure that’s around my neck to remember it. The sound is soothing because children often with developmental disorders, if you use a chime or a bell the high frequency sound just causes the alert circuitries in the brain to register a nuclear attack. So it produces quick and easily measured change that can grow bigger change over time.

Think about when you’re doing something. If you’re saying, “We’re doing an intervention, and it’s going to take 6 months to see any measurable change” you better rethink it, because you should be able to see micro-measurable changes in days or weeks maybe even minutes. Because that’s how nature works.

Now, they can grow and they can be used alone of combined with other kernels to create new programs or strategies. And most of the active ingredients, if you look at the list of the national registry of effective programs and practices on NREPP, most all of the ones with the highest level of effect size have, if you go back and read their bibliography, they have essentially evidence-based kernels that were all tested in single subject designs. So they have lots of active ingredients that are easily noted. They can be effective at a public health or population level, even spread by media or word of mouth, and they can help heal or reduce historic disparities.

I go to these damn adverse childhood experiences things; how many of you have been to one of those things? You all heard about adverse childhood experiences, the Kaiser Permanente Study, well just go sit through a day of that. Then people sort of forget they keep running on, “well you want to do that over in the Title One schools,” and “You need to remember that was done on middleclass working people in Kaiser Permanente.” So this is everywhere. It’s like a disease and trauma informed treatment. We’re just going to be, you know, we’re going to have a special ambulance every day running to pick up people. So better start thinking about trauma-informed prevention. We’ve got to think about those disparities.

Population-Level Influence

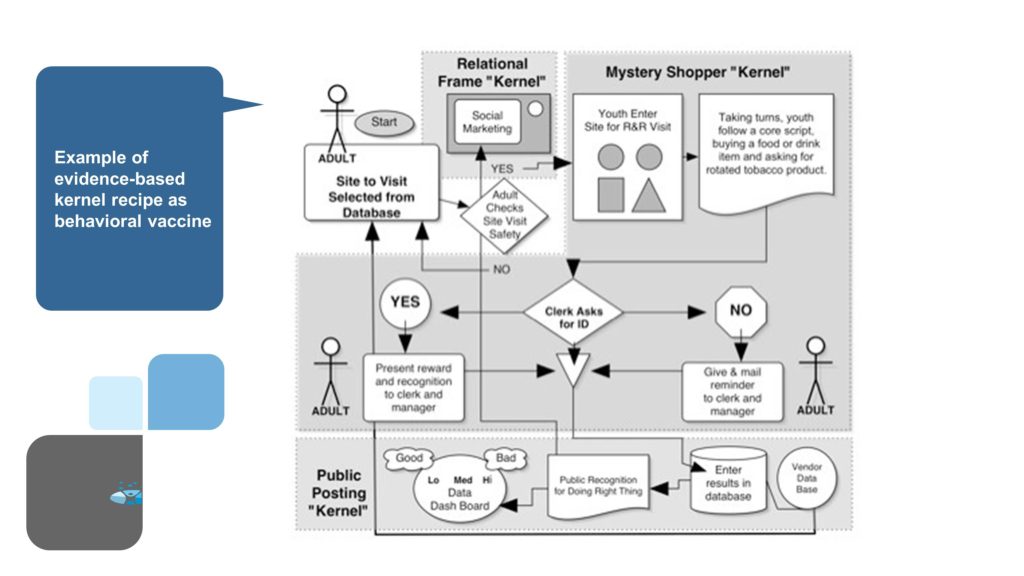

So, now here’s an example of an evidence-base kernel recipe as a behavioral vaccine. We have a relational frame.

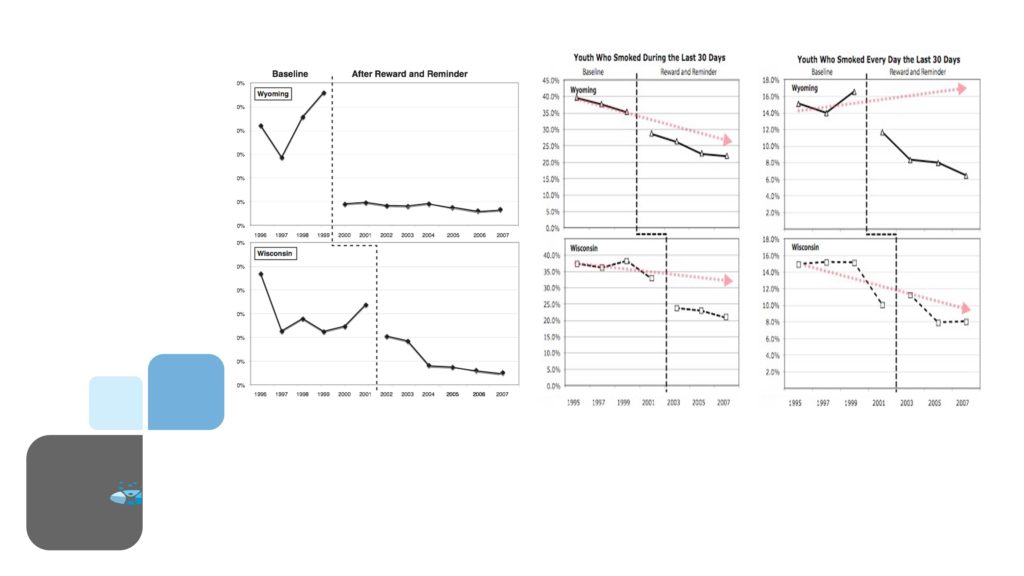

In Wyoming and Wisconsin we do the right thing by not selling tobacco to minors. That is the language of promotion. We have mystery shoppers which is an evidence-base kernel. The mystery shoppers go to the store, and do mystery shoppers look for the good or the bad? They look for the good. Because if you’ve done the right thing you get some kind of maybe not a Granny’s Wacky Prize but you get a gift certificate and an atta boy and atta girl kind of thing. So the mystery shoppers went out and reinforced the clerk and store, and they did it on public posting so we had a scoreboard every day for every single county in Wisconsin and those were announced on the radio station. So the kids who did the mystery shopping let’s say they were in Eau Claire, Wisconsin and they called the morning AM show. Every community has a morning AM talk show. So they call up and “Hi, this is the Wisconsin youth team, and we’re out at Bill’s Bait Shop at Lake Woggy Noggy. And we just want to tell you that Bill’s Bait Shop did the right thing by not selling tobacco to us minors, and they’re helping our youth be healthier and happier for their whole lives. So ring that bell on your radio show” Ding, ding, dong you know the cow bell rings, and we gave out cards to all the elected officials who that with their names printed on it that they could give to the managers of the stores or the clerks thanking them for doing the right thing. They said, “Well, how do we know if they’re doing the right thing?” I said, “We’ve gotten the rate down to less than 5% of the time that they’re selling tobacco. So you’re going to be rewarding most of the people and the poor shmuck who gets the card from you that sold is going to be reminded, oh this the community norm, hum.”

Next Steps

Questions and Discussion

Question: Clearly at some point you leave the evidence-based trail as you mix kernels together. You probably don’t have the time or money to test all those permutations. What is the method to get from kernels to packages and feel like you’re still walking the evidence-based walk?

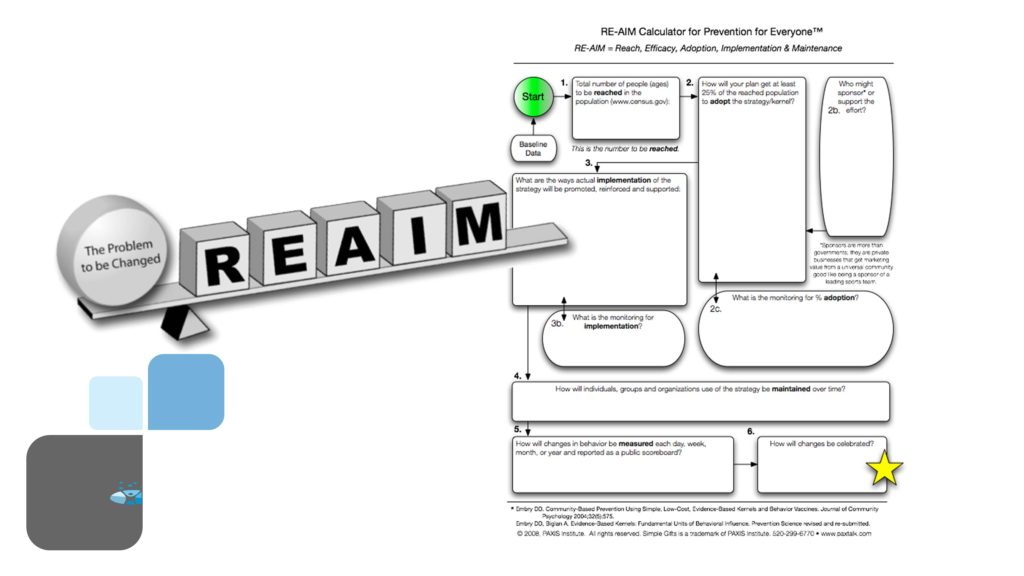

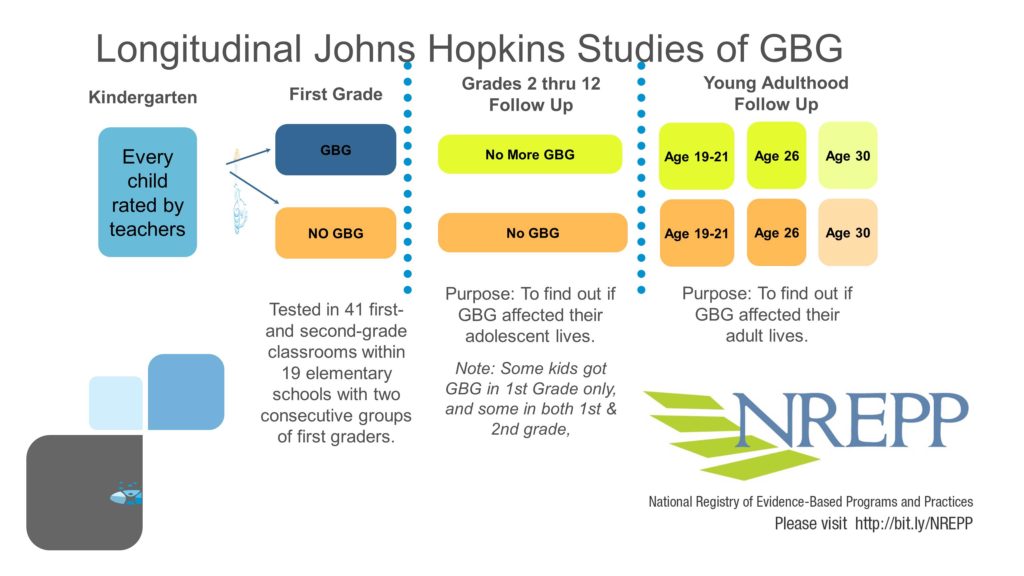

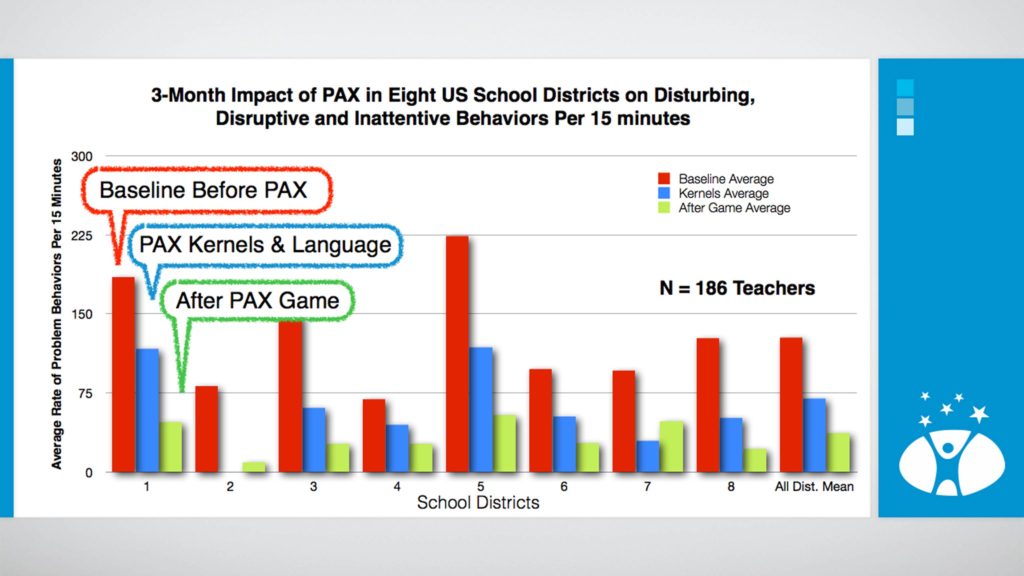

It’s a great question. So, the answer is continuous measurement. For example with PAX GBG, we have an operational measurement system that is measuring essentially engaged minutes — which is opportunity to respond. And we’re measuring the rate of disturbing, disruptive behaviors per hour. It’s a coarse one, but we use that as we do new permutations to keep looking at that. We’ve done this in more than 650 schools; thousands of classrooms, all 38 states, and now to Canada, Ireland, Estonia, etcetera. So we use those data to look at them, and we’re very alert for problems. And then you kind of tweak the permutation. The first thing we look for is the rapid rate of adoption, and then the sustainability

The other thing that we’ve done, and I suggest you do this, is never go for large print runs unless they’re dirt cheap. Because you’re going to wind up throwing away a whole bunch of paper. That way you can make incremental improvements. We use demand digital printing for our manual. Now, we’ve actually gone to offset because we’ve gotten it stable enough that it’s pretty reliable. That doesn’t mean that we don’t want to make changes, but we’re doing that very carefully. So have your ongoing measurement system that’s both for proximal outcomes and process outcomes. We created a rubric to measure those kind of implementation factors, and then monitor that and then every now and then.

We’re also very attuned to spontaneous innovations that people do. Some of them suck. Some of them are fantastic. One of them was a teacher, when we were observing in Syracuse. Normally the teachers announce what the disturbing, disruptive — we call them spleems, that’s a relational frame that controls the physiology. But the teacher asked the kids to predict what would be PAX (the good) and spleems before they played a game, and then asked them to debrief after. And as soon as I saw it, “Oh my God that’s self-regulation right there. We’re putting that in now. Why didn’t I think about that?”

Question: Looking at interventions, there is a great deal of reward to individual clinician researchers to develop an intervention that has their stamp on it, that’s associated with them. Having been involved in some projects that look at related interventions for a particular area, you see these common elements that I think could vie for status as a kernel. How do you break down the tie that people have to their particular package?

Question: You probably noticed you got a real reaction out the audience when you said, “Always do a single subject design before you move to an RCT.” A lot of us really love our single subject experimental designs, but most of us have also found that our grant reviewers don’t really love them. Do you have any tips on getting that practice through the levels of scrutiny from other fields that are not as positive about those methods?

Question: I was intrigued by your connection between Silicon Valley and Carbon Valley. When I think about Silicon Valley, I know one of the mantras was “Fail big, fail often.” How does failure fit into innovation and answering the questions that we want to have answered in Carbon Valley?