The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

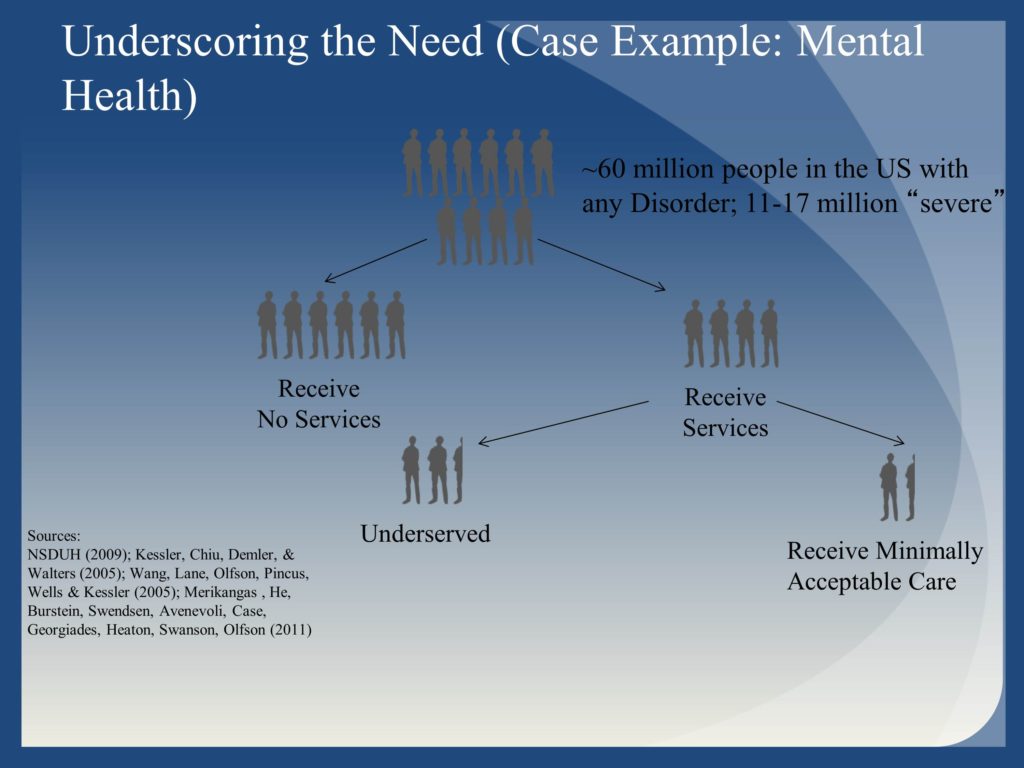

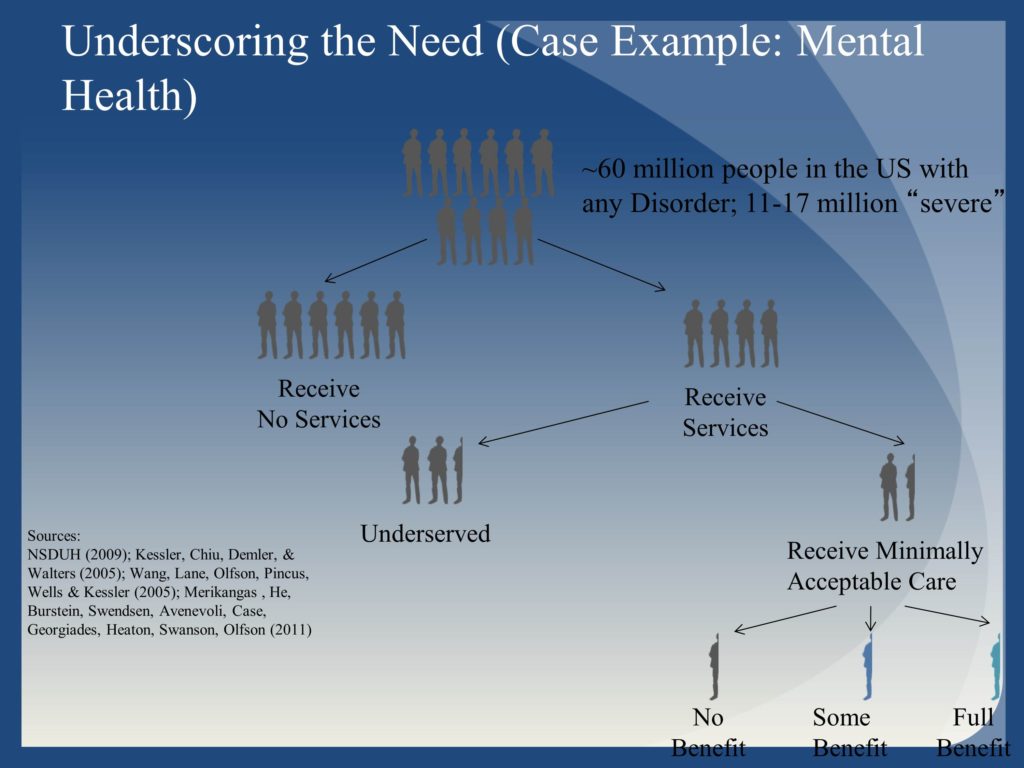

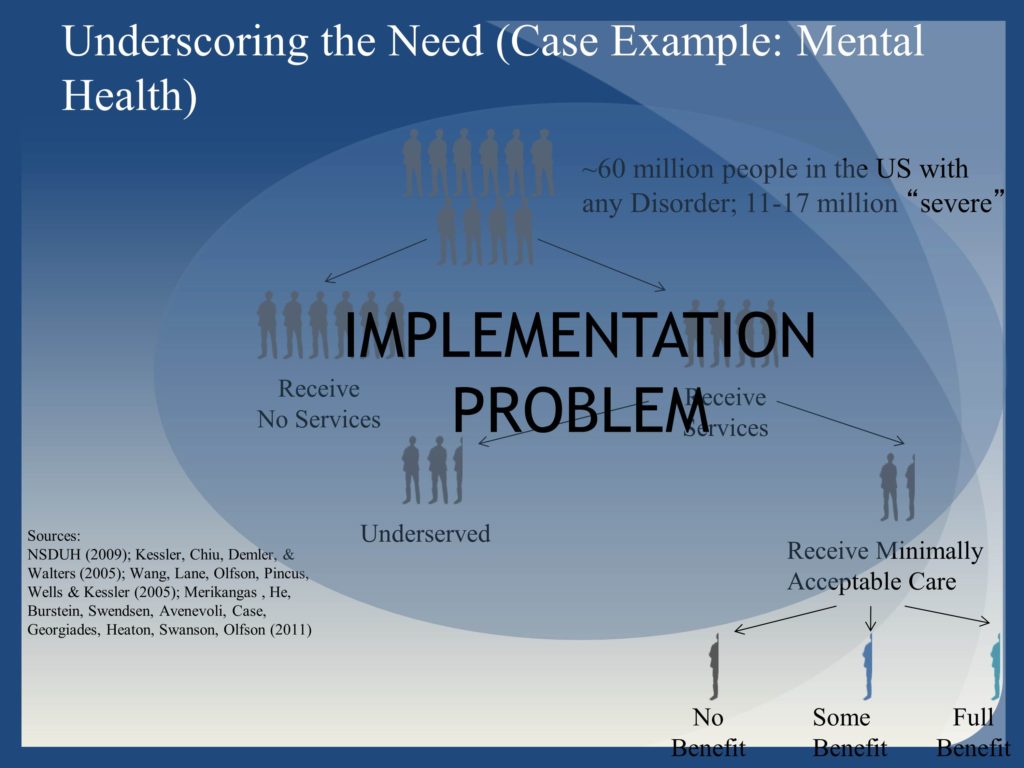

Conceptualizing the Challenge

Current Progress

Building a Better System

Questions and Discussion

Question: Are other NIH Institutes joining the program in dissemination?

Question: Thinking about conceptualizing projects that would fit into this, there must be lots of projects that come through that fit into our typical study section, as well as into D&I. Do you have any thoughts or suggestions about framing projects and making sure they go to the right place?

The more general answer is that this is why it’s so good to connect with program staff prior to submission. Program staff, who often have applications scattered across ten or fifteen study sections get a really good understanding of the nuances and the kinds of applications that may be most appropriate for any.

We do see within DIRH more and more of these hybrid studies, where they are trying to answer questions about the effectiveness of interventions while informing implementation. That is the committee that’s been receptive to that. But I would always start with, here are the key questions that I’m most interested in answering. Let program staff help to identify the right place. I think it can be a challenge to try and fit a particular study section. Especially if it’s not quite what you want to do. I think there’s enough diversity among the study sections and history of seeing different permutations with different levels of influence of say, intervention, effectiveness or efficacy with implementation, that I think the better thing is to have that individual discussion. Some expertise may be more abundant on certain study sections.

There’s not a perfect answer, but the best thing to do is have that dialogue and say, here’s what I’m thinking. Then in your cover letter, you absolutely have the right to specify, this is the committee that I think makes the most sense for the following reasons. That makes it easier for the referral offices to say, “Okay, that makes sense.” If it doesn’t of course they have the discretion to go elsewhere.