The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Point/Counterpoint: There are multiple paths to success.

There is not just one yellow brick road that takes you to social impact, R01s, tenure, pursuit of happiness and lots of stuff. There are lots of different roads of different colors and different difficulties. So the idea is this: What can we say about what those pathways are, and what are some guidelines that might be useful to you as you consider your own pathway?

What I’m going to do is to have two people who are going to do this point/ counterpoint. The first one is Professor Homer Heckle. Professor Heckle is going to take the point side of this argument. “And this is Postdoc or Not” So Dr. Heckle, would you take it away please?

“Professor Heckle”: A postdoc is the essential thing to do.

Postdoc or not? – Pro

There are a number of reasons why a postdoc is the essential thing to do. And here are some of them.

- It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity. Never again will you have the opportunity of being able to invest yourself completely in research. You will be free of teaching responsibilities. Committee responsibilities. And all those other things that populate the academic life. You’ll be able to concentrate on research projects. Day-by-day that’s what you’ll do.

- In the process, you’ll learn the skills and the culture of research. You’re going to be surrounded by other researchers. You’re going to think, breathe, sleep research. That’ll be part of your being. And you’re going to pick up lots of advice. Lots of guidance from people who have substantial research careers.

- You’ll learn how to compete successfully for grants. It’s a very competitive world when it comes to research grants. And there are lots of skills to learn. Lots of little tricks. Lots of strategies. By looking at other people as they prepare grants, you’ll get a better idea of how to go about this process.

- You will be able to promote the vigor of the discipline. In many fields today, for example neuroscience, psychology, getting a postdoc is almost obligatory. If you’re a neuroscientist, it’s almost impossible to get a job if you don’t have a postdoc. It’s not uncommon for people in neuroscience to spend 3 to 5 years in a postdoctoral position. Getting their skills; getting publications. What that does is to make neuroscience a very vigorous, research productive profession.

- Now if we have communication sciences and disorders where we don’t have a lot of postdocs, notice what happens. We’re going to have the weaker sibling. Communication sciences and disorders is not going to be as competitive, because the people who are applying for research grants, whether they’re R03s, R01s, or whatever, will not have the same kind of research background, and will not have the same research credentials as people in other disciplines such as neuroscience.

- You’ll learn about new methods and new topics in research. Maybe your PhD program didn’t give you everything you wanted to get, and there are some new, exciting ideas. And the only way you can immerse yourself in those is to go to a laboratory that’s active and to become part of that laboratory for some period of time. It gives you the opportunity to expand and to augment the skills, the knowledge that you acquired during your PhD program.

- It give you a chance to prepare papers for publication. So when you actually do hit the job market, you will have papers. You will already be published. You may have 2, 3, 4 papers. And that’s a good part of your credential set.

- And finally, you can develop your career plan. You will have time while you’re doing your research to think longer term. What are the kinds of situations that would be best for you.

Advice on Making the Most of a Postdoc

Now we have to be careful when we think about this, because the postdoc does not run itself. We have to consider carefully some of the things that would make the postdoc work. Because imagine this. If you’re finishing a PhD program, now you’re going to jump into some other laboratory or set of laboratories where you will undertake postdoctoral research. That’s a transition — a big transition. You also know this is a short-time position. You might be there for a year. Two years. Three years. Four years. Five years. Sometimes even more than that. So you’re thinking of moving into a position, but then also moving out of it, we hope, into a full-time job such as a tenure line faculty position.

So things to consider.

- First, the postdoc is more than a research job. It’s not just the situation where you do research. There are a lot of other things that happen. One of those has to do with professional development, which I’ll mention in a moment.

- So what you need to do is to make a plan. The postdoc does not run itself. You should be planning the postdoc carefully, even before you land in that laboratory. And you should have an evolving plan so that you can evaluate your postdoctoral experience as it’s moving forward.

- Ideally you get a head start. When you move into a new laboratory, there are lots and lots of things that take adjustment. And particularly, if you’re doing something like research with clinical subjects, there are lots of issues of recruitment. Lots of issues of the logistic type that need to be squared away before you can seriously get started. It’s very easy to lose months and months of your first year, because startup is very difficult and very challenging. Do everything you can in advance. Get a head start. Make the most of start times. If you need special equipment and it’s available to you, order it before you get there. Begin to have constant contact with your mentor at the postdoc institution. And be able to get as many things outlined as you possibly can.

- Take advantage of professional development opportunities. Most institutions will offer those opportunities in the form of lectures, seminars, and the like. You can also get various online resources. Think about your career the whole time. It’s not just research. You’re thinking about what happens afterward.

- Find a mentor and agree on your goals. It is very, very important that you and your mentor agree on what you want to accomplish during that postdoc period.

- In general, two or more brains are better than one. You want to get other people involved in your life planning. Particularly someone who is seasoned. Someone who has lots of experience when it comes to the world of research.

- Go international. If you possibly can, go to a conference. Maybe even develop some international collaborations. Network online as much as possible. And certainly develop your website.

- Learn how the hiring game works. You can talk with other people. How does it work? How do I apply? What do I expect when I go on a job visit? What should a job talk be like? How do I negotiate? All those kinds of things. Get pointers from people who’ve had that experience.

- Balancing work and life. First chapter in a lifelong book, because we’ll always be wondering, how do we balance those two?

And this is a general source of this advice. Making the most of your postdoc.

“Dr. Snyde”: A postdoc is a term of indentured servitude.

Postdoc or not? – Con

Change of roll. This is Professor Avery P. Snyde speaking now.

- Dr. Heckle, when I listen to you I think that your cortical association tracks are a bridge to nowhere. Let’s take a closer look at the postdoc shall we?

- First, it’s a term of indentured service. Yes, you’ll find yourself sitting in someone’s laboratory working towards their glory, but not necessarily your own. You may be there for three to five years. And during that time, one thing you’ll want to do is to get out. You’ll want your own tenure line faculty job. You want your own laboratory. You want to be in control of your own destiny.

- This is just a holding pattern. And we have thousands and thousands of people in a holding pattern. As already mentioned, in many fields, the postdoc is obligatory. So we have people who have no choice. There’s no job for them. We have an over-production of PhDs in many fields. There’s nowhere for them to go. Except we’ve created this wonderful world of the postdoc. Postdoc limbo I call it. So it’s a term of indentured service. You’ll be sitting there, whiling away your time. In the queue. Waiting for that position that’s going to open for you.

- Now, do you hear the clocks ticking? For whom do the clocks tick? They tick for thee. Biological clock? I hear it. Tenure clock? That’ll be coming. Mortgage payment clock? Another clock ticking. Retirement investment account. Should be ticking. All those clocks are ticking in one way or another, waiting for you to put money in. Waiting for you to have children. Waiting for you to do all those wonderful things that you have to do.

- Consider the potential loss of income in the term of the postdoc. And we’ll look at the graph that displays that a little bit more. And consider that as you’re in this postdoc position, any debts you’ve accrued to that time, you cannot pay off. You’re going to have to wait. Because you’re not going to be making a lot of money to pay them off. So you’re going to be, again, in this holding pattern.

- You also will find that if you don’t want a postdoc, that at least in communication sciences and disorders, positions are readily available. You can find a job without a postdoc. And I’m sure if we interrogated some of the mentors in this room, we would find that they did not have a postdoc, but they seemed to do alright.

- You can jumpstart your career by skipping the postdoc. Why take the postdoc? Why not jump directly into what you want to do, which is teaching and research. And remember, those publications you get during your postdoc, they’re not going to count a great deal, because when you get a tenure track position, they’re going to be giving emphasis through the publications you earned while you were working there, at that job. Oh they won’t hurt you to have some previous publications. But after all, what the institution is worried about when they hire you, is will you be productive in place where you are?

- And by moving directly to a faculty position and skipping the postdoc entirely, you move to independence as a teacher and a researcher.

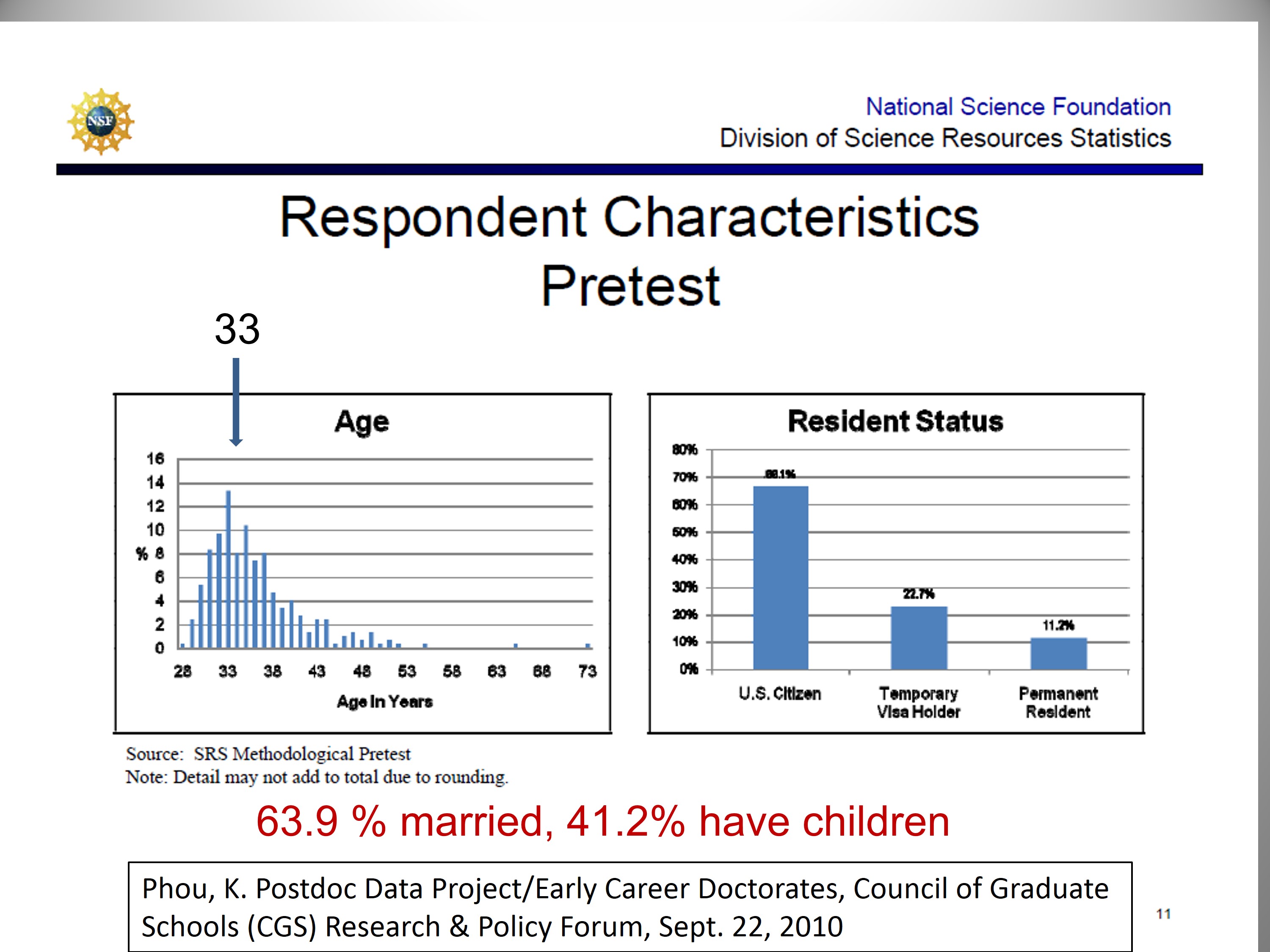

Characteristics of a Postdoc

Now let’s look at some of the characteristics of a postdoc. These are data taken from a survey. And as you can see, what we have are respondent characteristics. This is in part of a larger study, so this was a pretest. The average age of the postdoc is 33 years. Notice that 63.9% of them are married. And almost half — 41.2% have children. So they already have family responsibilities for the most part. They’re getting older. And you can see some of those postdocs are reaching up into the 50s. But most of them are between the ages of — oh it looks like about 25 to 35. Most of them are US citizens.

Average Debt at Graduation

And let’s consider these postdocs. Many of them went through college and had to borrow money. The average at graduation from a 4 year college, this last year, approached $30,000. According to the report Student Debt in the Class of 2012, if you went through a masters programs and had to acquire additional debt, you may be well looking at something in excess of $30,000. And it’s not unusual to find students who have anywhere from $50,000 to $60,000 of debt. So here’s this big monster in the room, waiting to be paid off.

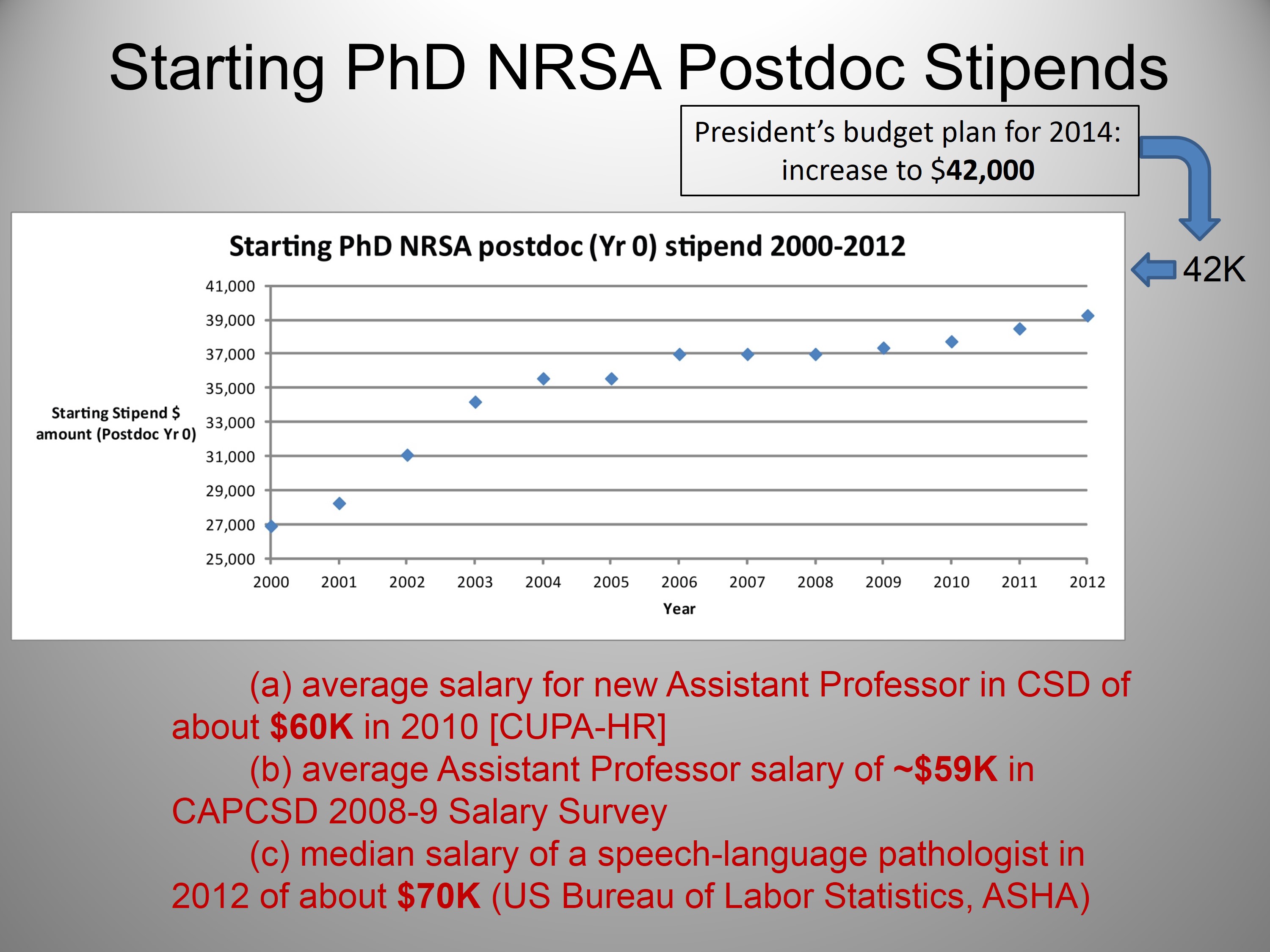

Starting PhD NRSA Postdoc Stipends

What do postdocs earn? Well these are the starting PhD, NRSA postdoc stipends. And notice that they were static for many, many years with a very small increase around 2012. Francis J. Collins, Director of NIH and President Obama both have supported an increase to $42K and Dan Sklare will tell us later if that came to pass. I haven’t gotten past page 3 of the US budget. So I haven’t gotten this far.

But notice in comparison. The average salary for a new assistant professor in CSD in 2010 was estimated to be about $60,0000. The average assistant salary of about $59K in the CAPCSD survey of 2008/2009. And the median salary of a speech/language pathologist in 2012 was about $70K according to the US Bureau of Labor and Statistics and data reported by ASHA. In other words, every year you are in a postdoc, even if you get this wonderful, elevated pay raise to $42,000, you’re losing easily $20,000 per year. If you’re in a postdoc for 3 years, you’re losing easily $60,000. Furthermore, you’re not making contributions to the retirement plan that you would eventually have if you took a faculty position. You’re not getting some of the other perks and benefits that go with a faculty position. And you’re not making progress towards tenure.

Factors Related to Successful Experience: Postdocs vs. Supervisors

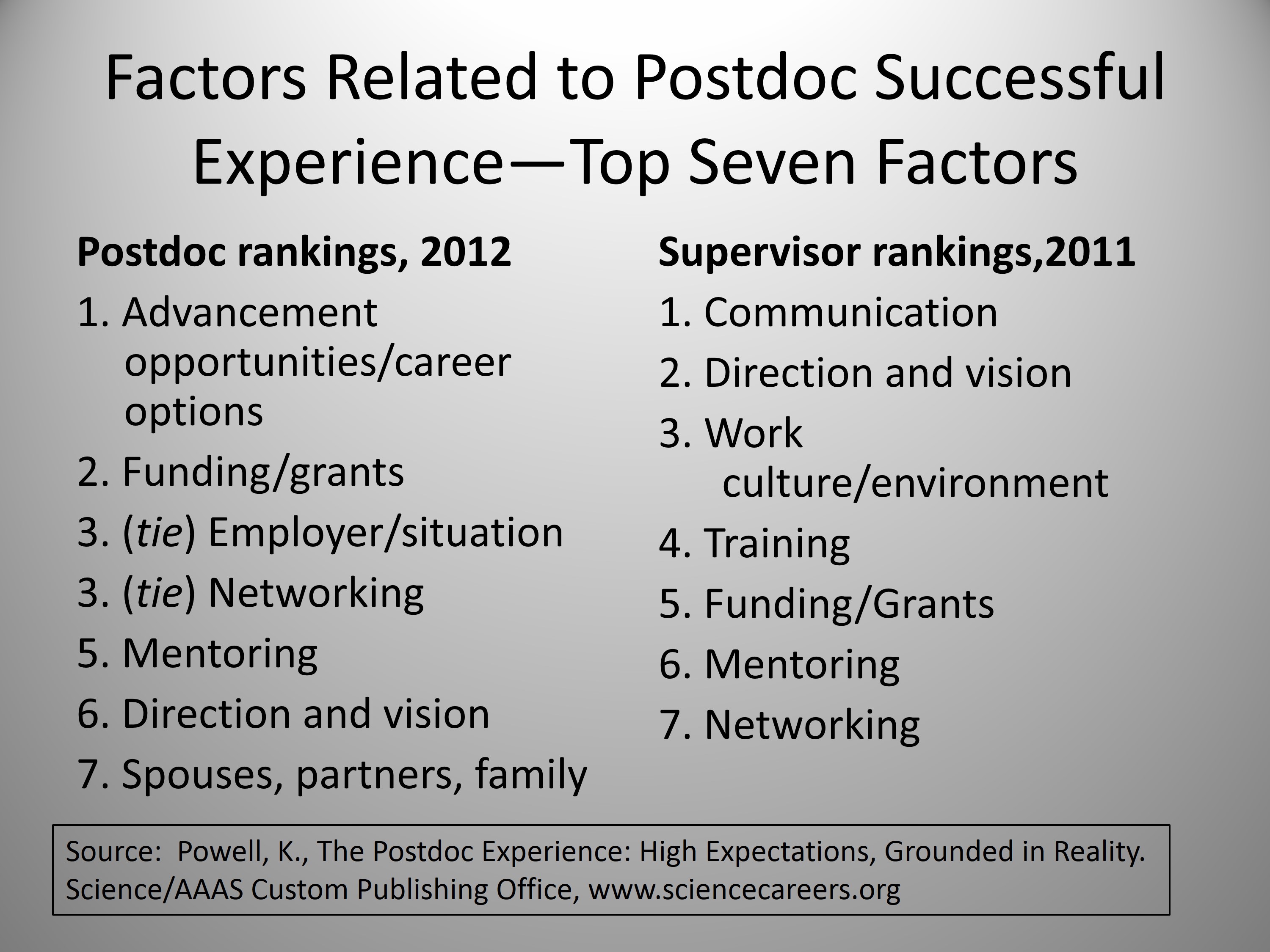

Factors related to postdoc successful experience. And all I want to point out here, is when they surveyed postdocs, and then they’d surveyed the people who supervised the postdocs, they determined a ranking of the most important characteristics.

So as to the postdocs, this is what they had to say. That’s to your left. What’s important: Number one, advancement opportunities and career options. That’s what they really want to know. Now notice on the list of supervisor rankings, do you see that item? No, it’s not there. We have a mismatch between what the protégés, the postdocs themselves wanted, and what the supervisors thought was important.

Well the supervisors were well-intended. They said communication. We all say communication. If you’re married, you gotta communicate. Got kids? You gotta communicate. Thing is, what do you communicate? And notice what we saw on the side over here are the postdocs. They had specific things that they wanted to get from that communication. Things like advancement opportunities. Career options. Funding. Grants. Employer and situation. Networking. Mentoring and so forth.

So one of the problems with the postdoc is it doesn’t necessarily guarantee that the person who is supervising the postdoc will provide what the postdoc really wants and needs.

Postdocs are not particularly standardized. So each one of them develops, in its own way, depending on the unique chemistry of that institution, that mentor and that postdoc. That’s why planning is so absolutely important. I’m not saying you shouldn’t take a postdoc at all. If you got a lousy PhD program; you don’t learn anything, yeah. Well get a postdoc. But if you do have a good PhD, and you are ready to be an independent researcher, you don’t need to go this route.

References

Smith, Z. & Sutton-Grier, A. (2010). Making the most of your postdoc. The Chronicle of Higher Education.