The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

What is the most important building block of a research career? Publications. Something we all know and love and dread.

I’m going to take you through some tips that we use in telling people how to publish something and get it out there in the best format possible.

Your publication record is the thing that defines your career, defines who you are, and defines your reputation. This is the core that goes to grant committees, that goes to tenure committees, that goes when you apply to jobs, so it’s essential.

You have to get the papers out. Sitting on your desk doesn’t mean that they count. They don’t count until they are in a peer reviewed journal. That’s the only thing that counts.

Most important — do not waste time doing chapters. Chapters are something that you can do when you get old like myself and have lots of white hair. As you’re early in developing your career, don’t spend time on them. One more chapter, one less paper. The papers count.

Requirements for Authorship

There are now requirements that are published by most journals. There are sort of three stages to a research study. One is the conceptualization or the design. The second is acquiring the data. And the third is analysis and interpretation of the data. Then finally, writing the manuscript.

There are now requirements that are published by most journals. There are sort of three stages to a research study. One is the conceptualization or the design. The second is acquiring the data. And the third is analysis and interpretation of the data. Then finally, writing the manuscript.

To be an author of a publication, you must have participated in one of the top three, as well as participated in the manuscript writing. Of course, you have to have had a role in reviewing that final manuscript before it goes in if your name is going to be on it.

There are lots of discussions about authorship, as I’m sure all of you know. That should be revisited at different times during a study. It should be discussed very frankly, and in a very business-like fashion at the beginning of a study. People’s roles change over time. Somebody gets sick, somebody leaves, a new person arrives. So it’s important to revisit that as you go along.

Selecting a Journal

Selecting a journal is really important. When I was at NIH, I once had an Institute director called me up and say, “Why did you publish that article in a low- impact journal?” Well, it happened to be a journal that was important for my field, but the impact score was a 1. To her, that was a total waste of a publication. It probably turned out to be a highly cited publication of mine, but certainly your review committees and grant committees will look at how high-impact a journal is that you publish in.

Why is high impact important? The citation rate for high impact journals is much higher. That’s how they get high impact scores. They are rated based on the citation rate of the articles that they publish.

So you want to look at the ratings of each of the journals. Many of our journals in our field are down at 1s and 2s. That’s low impact. Writing for a high impact journal means you have to make our science attractive to people in other fields. That’s a sell job. So picking your journal before you write your article is going to be essential because that’s going to determine how you’re going to write it.

You want to look at the mission statement of a journal, you want to look at the articles that were published in that journal. Your topic or which journals are other people publishing in. There’s a program called Journal/Author Name Estimator (JANE) which allows you to enter the title or abstract of your paper that you’re planning to publish, and it will find journals based on the content and the words that you use.

I often also go into Medline and do topics that are related to my topic and find out which journals some of the recognized leaders of the field are publishing in.

Start with Your Figures

So you’ve worked your butt off, you’ve got your data, where do you start in writing this up?

A lot of people sit down and start writing the introduction. Bad thing. Not a good way. An introduction can go on and on and on. Because there is always more data and information to cover. The introduction is going to be one of the last things you write.

You’re going to start with the results. Take all your data. Find out which is the most important data, and organize your results according to that. Spend time on making sure that your figures illustrate your major findings.

You don’t want to do tables. Tables are boring. Nobody likes to read them – particularly reviewers of articles.

You want to have figures that make your results clear. Not bar graphs, but rather box plots that show the variation of a group. You want to demonstrate as much as you can on what happened in the data.

I do not do tables unless I really have to. And often I’ll put them in as supplementary material.

With box plots, never show just means. Always add standard deviations or standard errors.

If it’s a repeated measure, people being studied over time, I often have a line for each subject and show what everybody in the group did. It’s a much better way to illustrate a before and after result.

Then Write Your Results Section

After the figures are done, then you will write the results section. You start off by stating the hypotheses for the study. That will also be the end of the introduction, and you’re going to go back to the introduction later. But you start off by writing the hypotheses. Why? Because that’s what you had to answer, and that’s what your results have to address.

If you have several hypotheses, start with the first hypothesis. What did you find? Have a figure to show that, if it was something important. If it was non-significant, don’t waste time and space on a non-significant result, just put it in the text.

Write up each one of your hypotheses, which were the questions of the study.

Discussion Is Next

After the results section is done, then you go to the discussion. Because the discussion is taking your results and placing them in the science. How do they relate to what other people have found, how do they change the field, what’s the impact of what you found? Don’t write up what you plan to do next, that’s not important for this study.

You want to make sure you’re communicating what your final results were and how they compare with other people’s results and what they clarify.

Limitations. Put your own limitations in, don’t let the reviewers write it for you. Make sure you acknowledge what your limitations are and address that in as best you can.

Then do the final conclusions. So the discussion is taking your results, putting them in the context of the field, and interpreting them that way. Show where you differ from other people’s results and try to interpret that.

Write the Introduction as a Justification for the Study

Now you go to the introduction, because now you know exactly where you’ve gone with this study. The introduction is not a review of the literature. It’s an argument for why this study had to be done. What you’re doing is a logical argument of so-and-so has found this, so-and-so has found this, these two pieces of results differ. They might differ because of X=Y, therefore you need and absolutely have to have a study determining whether X=Y. It’s a logical argument on why this study had to be done, and what the importance of it is.

Methods

Methods. Try to keep it as succinct as possible. Sometimes people are replicating something that they did in a previous study, and so you can cite the study and say, such-and- such was done similar to — and refer to the previous study, rather than repeating yourself entirely.

If the subjects participated in any other published study, it definitely has to be included in the subjects description that all of these subjects were already studied and published in a previous study. You can’t be showing this as though it was a completely novel group of subjects.

Then organize your outline for your statistical methods and your data analysis according to the hypotheses. That will make it very easy for the person who is reading this to then go from the introduction (which ends with the hypotheses), to the methods (which is organized by the hypotheses), and to the results (which are organized by the same hypotheses). This makes it much easier for the reviewers and readers to follow the findings in the study.

Write the Abstract Last

Next Steps

The next step is you have to send it to all your co-authors. Make sure they agree with it, and get their permission to submit it. You absolutely have to have their written permission before you can submit anything with their name on it.

Then, people often forget the essential point of selling it to the editor of the journal. The letter to the editor when you submit an article is absolutely essential. You want to sell your study, say why it is important to their readership, and why they would be interested. How many of their readers might be finding this a significant study.

Revisions

As long as they don’t totally outright reject the paper, you should revise it and send it back.

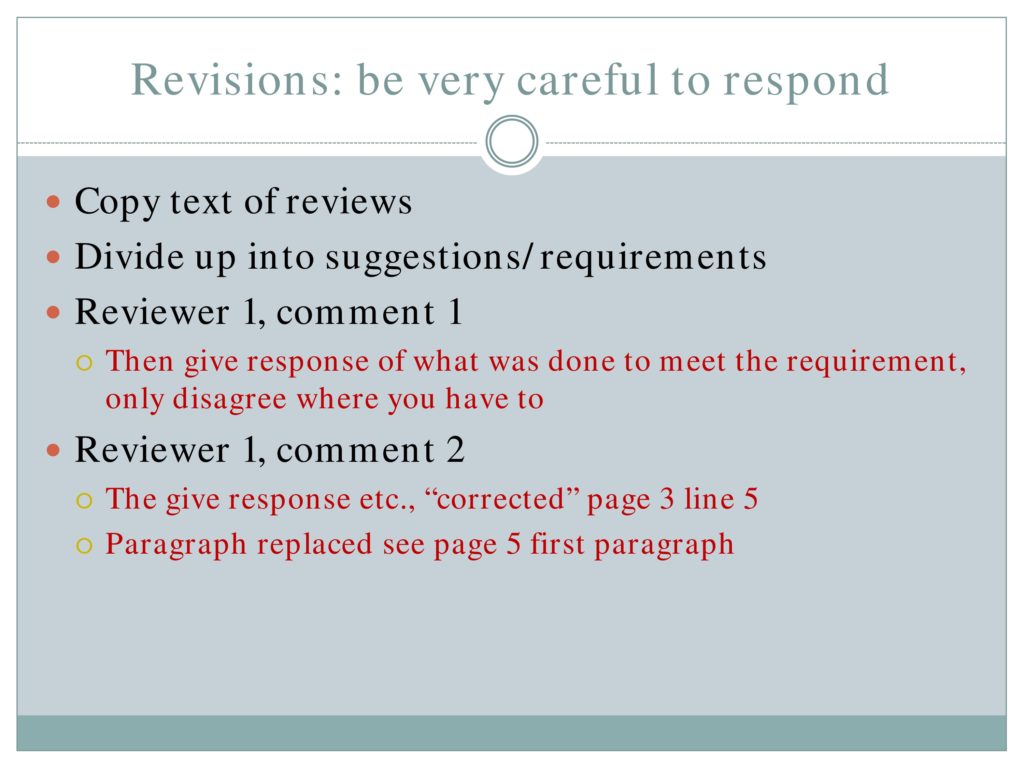

When you revise and send back, be very responsive. List all of Reviewer 1’s comments . After each comment, say what have you done in this manuscript to address that comment. Sometimes you may want to justify something that you did, still add that justification into the manuscript, too, so it shows you were responsive in addressing their concerns.

Always say where you did it. When they get this back, the reviewer is not going to want to wade through the 20-page article to find out where you changed your reference to so-and-so. Always give the page and the line number where you made that change.

Rejections