This presentation was delivered as part of a workshop session on the application of adaptive design principles to clinical trials in speech-language pathology. Susan Langmore, a swallowing researcher, discusses challenges in her clinical trial, while Sharon Yeatts, a biostatistician, provides her thoughts on potential opportunities and pitfalls in integrating adaptive designs to this work. For an overview of adaptive designs, see Adaptive Trial Designs for the Development of Treatment Parameters.

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Susan Langmore, Boston University:

What I’d like to do is talk about the clinical trial I ran and how I wish I had heard Sharon Yeatt’s talk six years ago, because there is a lot that I would have changed.

The Phase 3 Trial Design

This is the trial that we ran from 2007 to 2012, although we just are still finishing analyzing the data, and my co-investigators were Cathy Lazarus and Jeri Logemann, and Tim McCulloch, and Doug Van Daele. And then it blossomed into many many more people being involved, which I’ll get into.

So our design was a Phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Patients with head and neck cancer three or more months post radiation or chemo radiation with moderate or severe dysphagia. They were randomized to one of two groups, and we had a two to one proportion; twice as many of the patients got electrical stimulation, surface electrical stimulation, and swallow exercises, and these were swallow maneuver exercises. A certain kind of swallowing exercises, three of them, and some stretching.

The other group, one third of the patients had sham estim, and the same swallowing exercises, and the same stretching exercises.

It was a home program; they were taught to do it, and then they were sent home. It was intensive; they did it twice a day each session took about 30 minutes, so that’s an hour a day, six days a week, for three months coming into the clinic once every three weeks.

The outcomes were penetration aspiration scale, diet, quality of life, and other swallow measures taken from fluoroscopy.

We didn’t precede that with a Phase 1 or two trial, and I thought about that as I was writing this up. The toxicity, if you’re thinking toxicity not tolerability of estim or exercise after radiation therapy is over was considered low risk. I think we were strictly thinking of that and we–there’s was no–so there was no Phase 1 trial done.

A Phase 2 would have been great for several reasons. The most effective dosage was not determined, and has still not been determined. For this group or many others, we examined what we thought was a very aggressive dose; what we thought they would tolerate.

And what it turned out–actually I’ll just jump ahead is compliance was very good. I don’t think it was too aggressive. Most of our patients did 100 percent or certainly over 75 percent of what was prescribed.

But the other questions, the effective exercise, swallow maneuvers as an exercise and/or estim had only low level evidence with head and neck cancer patients. We had some pilot data, there have been case series, but with that population, really nothing has been shown to be really efficacious, which ironically was one of our arguments for doing this — that we really needed to try something, and this hadn’t been done.

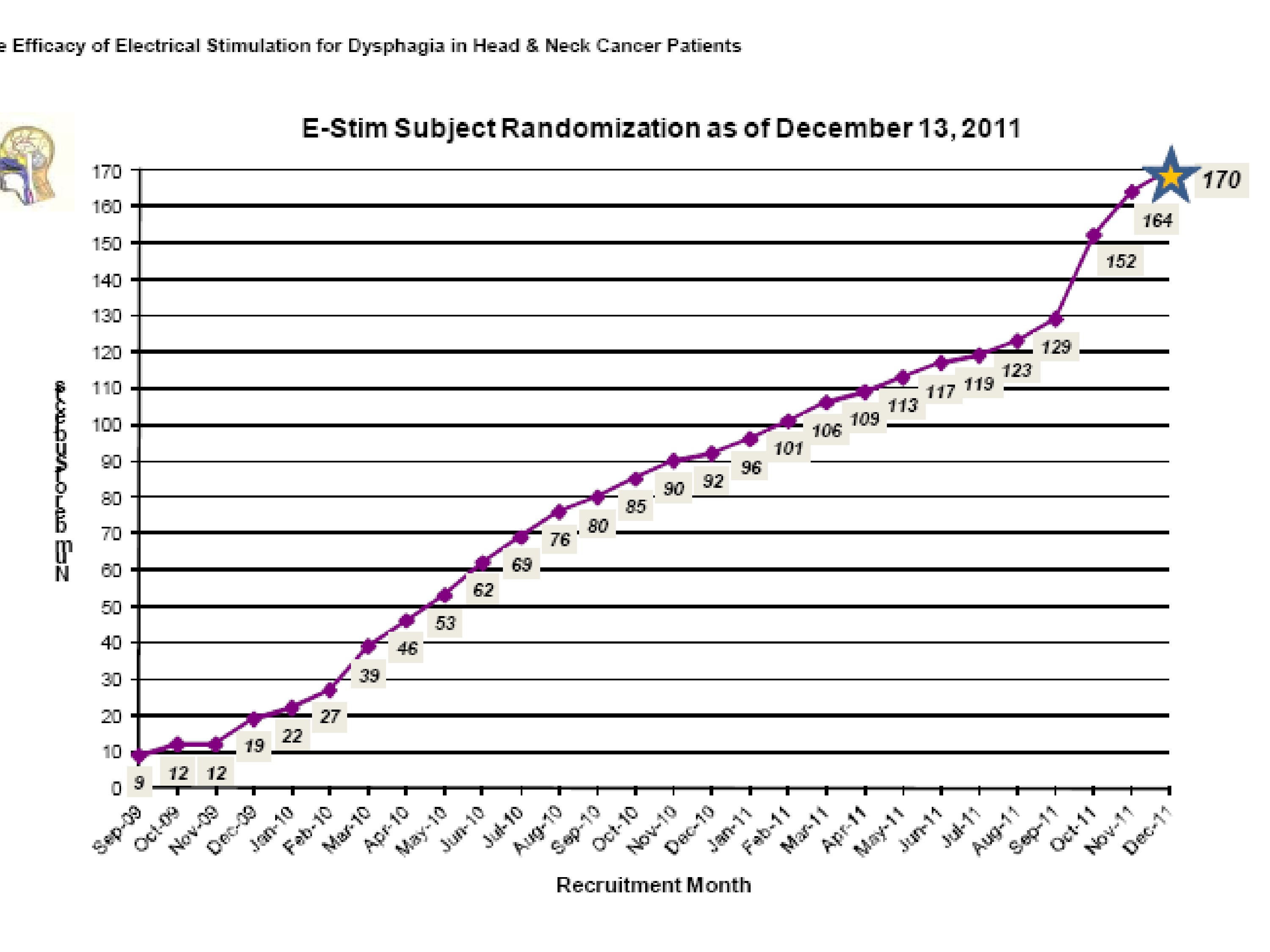

So our–we did reach 170 patients which wasn’t completely as many as we wanted, but it was enough to stop, and the funding ran out so that was another reason we stopped.

Major Results

Our major results we had two questions- were there significant differences in the two groups, the real–we called them the real estim, the sham estim, but remember they all got the exercises at the end of treatment, adjusted for differences in baseline performance.

And it turned out there was only one significant difference, and that was the penetration aspiration scale for thin liquids and overall taking all of the boluses.

However, the sham group performed better than the real estim group, so that was a surprise.

The next question was, and I’m jumping through this quickly of course, did either or both groups make significant improvement? There was no difference between the two, but did either of the groups make significant improvement? And yes, only for diet and quality of life, but not for any swallow measures except the sham group for penetration aspiration.

So we were left with the kind of trial where we were twiddling our thumbs and wondering what did it mean. We concluded that estim did not add any benefit beyond the swallow exercises, which actually didn’t seem to add any benefit either, and that swallow therapy using swallow maneuvers as the exercise and stretching delivered after chemo radiation may improve patient’s diet and quality of life.

They all reported that diet and quality of life was significantly better at the end. So those were our positive outcomes in the absence of many swallow measures that would support it.

So estim did not add benefit, the swallow therapy delivered after chemo radiation may improve diet and quality of life, but may not improve swallow status as measured by PAS and some other measures.

Major Obstacle

So I want to mention some of the problems and maybe have your input or the audience’s.

Accrual of patients was very difficult, and this led us to have to alter the design, and I think that was very unfortunate. Five sites were not enough to collect the data.

We ended up with 16 sites over four years, and that was good. That was fine. It took a lot more planning, but we ended up with lots and lots of sites.

But the most important thing I think is the eligibility requirements had to change, so instead of getting the most significant and you had to aspirate, we said penetration was okay.

And that I think is okay, but the number two, instead of looking initially we had wanted to look at three to six months post radiation time only; a very narrow window, not too long after radiation. And what happened was we had to expand it to we’ll take you anytime from three months on up to several years, so it turned out that our patient population in the group was the mean was four and a half years after radiation, and the range was anywhere from 3 months to 22 years. So a huge range and in years. I’m sorry, that’s a typo, not large range in severity, a large range in years.

You know head and neck cancer post radiation poses its own problems that, and that is this late effect. After radiation we have a late affect after 5 years; we have a late affect after 10 years.

And so it makes it really hard to think about how to design a trial to look at late affect unless you’re willing like the Framingham Study to stick with them for 10 years.

What Would I Change?

So what would I change? I don’t think for ours a Phase 1 was necessary. That may not be true if you’re doing patients during radiation; that’s a big issue if you’re doing people during radiation. Compliance is reputedly very poor because they’re in pain. They’re getting radiated, they’re tired, they may get chemo too. Compliance is not real good, and so that’s a big issue during, but in our group it wasn’t.

But a Phase 2 trial could have looked at several things, different intensities of therapy. Well, I don’t know ours was pretty intense and seemed okay, but different types of exercise; we tried three specific swallow maneuvers. We don’t know if others would have been better. And no one had ever shown this.

In fact, to date, there’s only a couple of trials that have shown long term benefit from a swallow maneuver. Gary McCulloch lately looked at Mendelsohn Maneuver, and found good outcomes for stroke patients. No one’s found efficacy for head and neck cancer patients after radiation, or time post chemo radiation.

And I think that’s where the field is narrowing down to; they’re saying well, maybe the earlier the better, so it could have been–I think the big question is in this population when is the best time to intervene?

There’s some evidence that intervening during is beneficial, but we get a lot of patients directly soon after radiation therapy and we wonder you know what about this zero to three months after? Maybe this is not too late, and maybe I can make good progress with them then and they’d be more compliant. How about three to six months? Three to nine months? And so we didn’t answer this question, but I’m wondering if that’s the kind of design that would be really useful for the field.

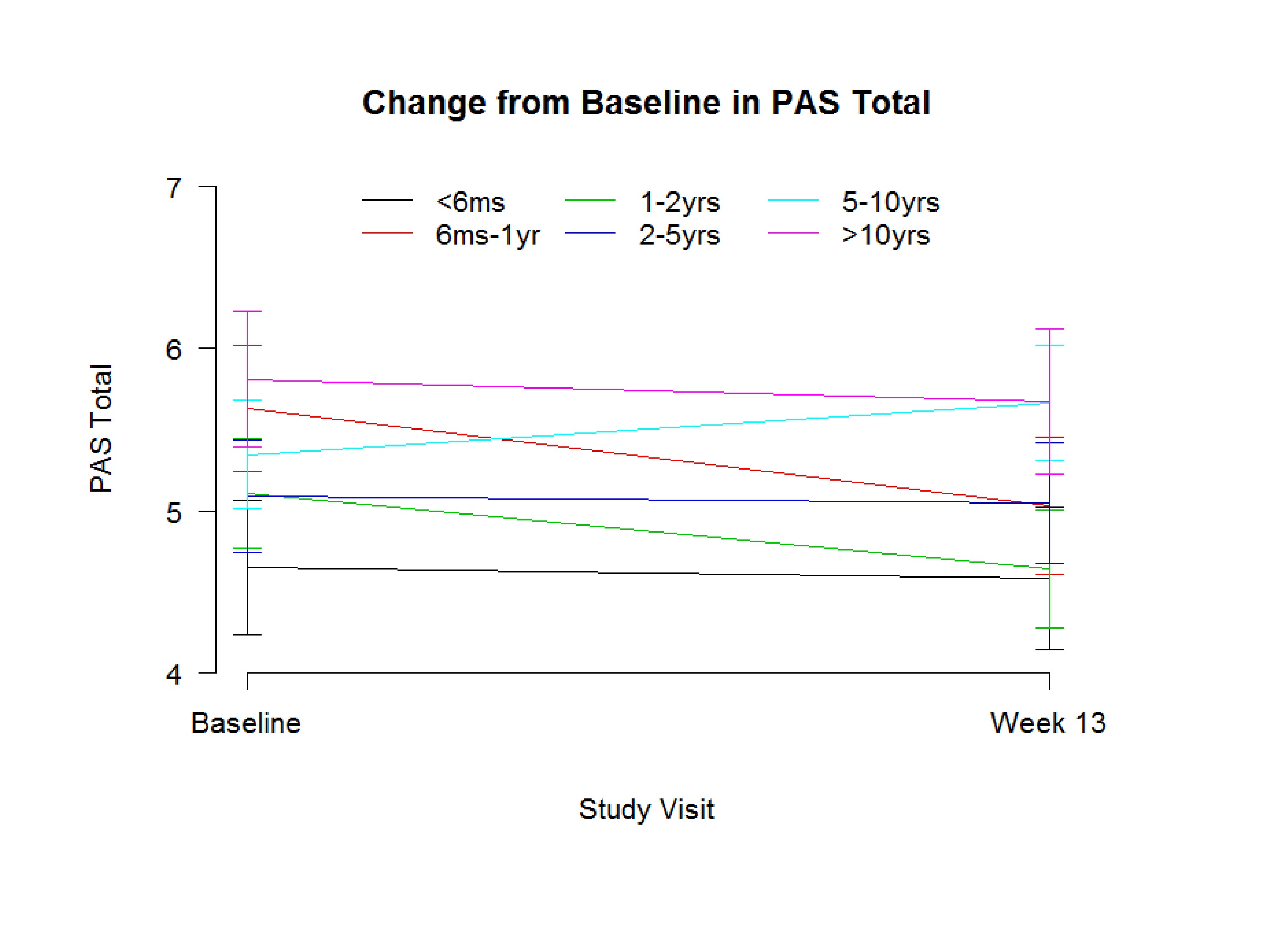

I want to show you this. We just got this and it’s not looking in one patient over ten years, but we had a fairly equal number of patients who were less than six months, and if you look at the change in PAS. Now remember we couldn’t enroll them unless they had a PAS of four or higher. And this is the standard deviation, but the group that was six months, was zero to six months, less than six-months post radiation they did have the best PAS score; the lower is the better.

The group that was ten years or out were the most severe. Now, we can’t say over time you get worse because we enrolled them at 10-years post. But that would be the kind of question you’d want–you’d really want to know, do they get worse over time?

Our patient population, yes, the further out the worse they were. And then you look at who got better, and the one to two-year group did get better in the penetration aspiration scale. And I believe this is the six months to one-year group did get better. So over the 12 weeks of therapy, the three months of therapy, so maybe that does mean this group over time is more amendable to change, and we should be–and maybe overall because we had patients 20 years out, we didn’t see many changes in swallowing, but the patients who were just zero to six months out, and six months to one year out did do better.

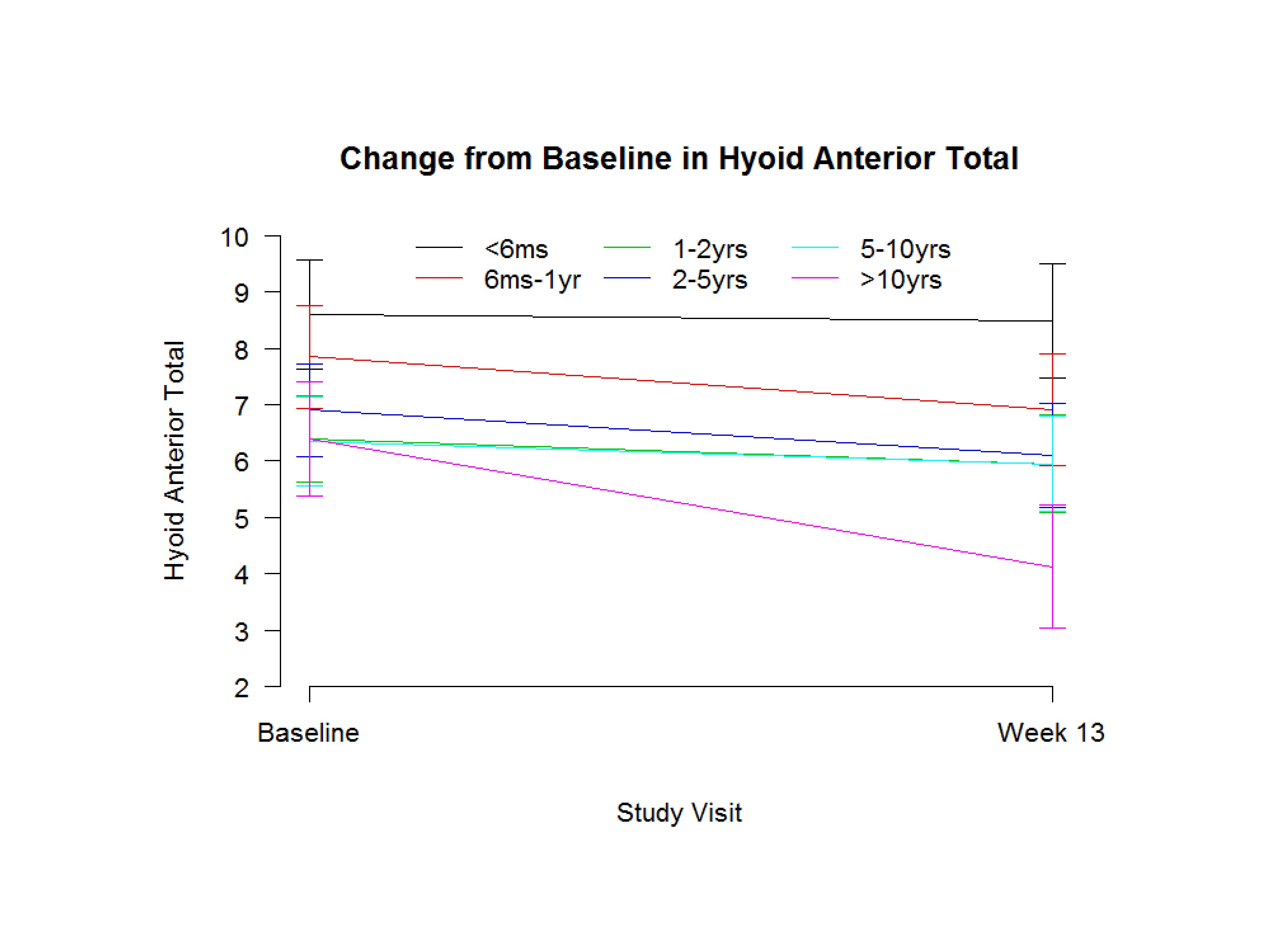

And this is just another one–Hyoid Anterior Total. The six-month group had the best anterior movement; this is millimeters. But the group that’s ten years out they were the worst, and they got worse over time, which is very surprising. But they–you know certainly in our population, in our trial, the group that was five to ten and ten years out were the worst.

Sharon Yeatts, Medical University of South Carolina:

So I describe the phases of clinical development, because that’s how most folks are trained. But to really think outside the box when you’re trying to think about these questions and not maybe think too much about which phase it goes in.

So this question of when to study these patients is a really nice example.

I talked about those modeling designs as being dose finding, but there’s no reason that in a pilot study you couldn’t think about along the x axis the time out from the radiation treatment and figure out what that dose response curve looks like and try to figure out where is the optimal place to intervene.

There are other ways to incorporate some of these other questions that we have. The hardest thing, right, is to answer questions that address variables that we have no control over. Like the time from treatment end. In one of our studies we were trying to establish whether treatment had to be initiated within 12 hours or we could get all the way out to 24 hours, and there are very nice statistical ways that you can do that.

You can think about in a more complicated question where you have so many groups, because you’re taking patients all the way out. You could think about enrolling patients in sort of bins that correspond to time, and during the course of an adaptive design dropping the bins that aren’t being helpful.

You could think about actually designing a study to answer that question. Sometimes the factorial design works really nice where you’re comparing two interventions with a couple of different time intervals, and you want to be able to say maybe one intervention works better in those later patients, and another one works better early. But it–you do have to kind of think out of the box and really think about which question you are trying to answer.

It’s actually easier to do that maybe than to convince the funding agency that that’s the question that needs to be answered before you can go forward. But there are definitely ways to incorporate those sorts of questions on those variables that we have no control over into your designs.

And of course we try to do that as early as possible, because as you’ve said once you get to the end and you can’t say anything it is really hard then to convince folks that well maybe if we had changed this it would have done something different.