This presentation was delivered as part of a workshop session on the application of adaptive design principles to clinical trials in speech-language pathology. For an overview of adaptive designs, see Adaptive Trial Designs for the Development of Treatment Parameters.

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

The Need to Optimize Therapy Prior to Clinical Trials

It occurred to me that when we look at the history of clinical trials in our field, that this concept which comes primarily from pharma and from drug trials and also chemotherapeutics for cancer, might be extremely adaptive to our areas of interest. Because we do not know if we have the optimum treatment to study before we go into a clinical trial. And really what this does is allow you to determine what would be the best way to handle your treatment.

Now in pharma and chemotherapy, they’re often worried about toxicity. And so what they’re trying to determine is the best ratio between how much of a treatment is toxic and will kill the patient and how much will benefit the patient without killing them.

So we don’t have that problem in most of our cases. We’re more concerned about fatigue and other issues like how many times can the patient come into the clinic and partake in therapy. But so those are very real constraints. They’re not as dangerous for the patient but they are constraints. And we need to know what kind of therapy approach and how intensive it would be to try and optimize therapy before we do clinical trials.

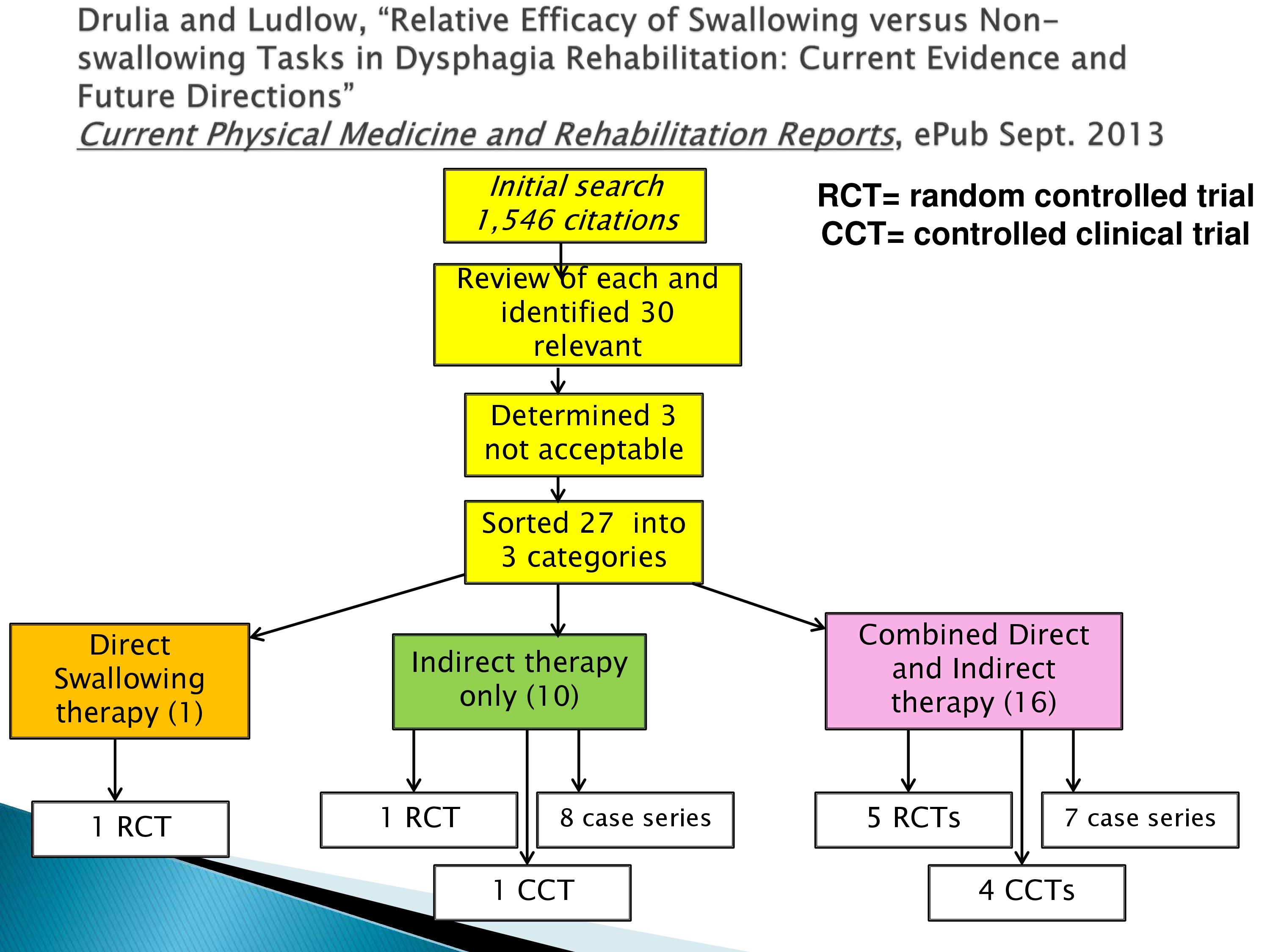

Now one of the concepts of this started when I did a review last summer for a journal and they wanted us to discuss what had been done in the last two years in clinical trials in dysphagia. And they wanted me to address non-swallowing tests and swallowing tests. And this turned out to be a different kind of study than we envisioned. We thought this would be a snap. How many clinical trials are there anyway? And we had quite a surprise. There were quite a few random controlled trials in a two year period in dysphagia.

We started off reviewing everything in the literature. Then we honed it down to what were clinical trials or controlled clinical trials where they didn’t have random assignment. And we ended up with three batches.

The yellow batch over on the left which was one trial where people did just swallowing therapy. In fact, in this case, the Mendelsohn Maneuver.

Another where they did indirect therapy. That is some other therapy that wasn’t directed towards swallowing.

And then a third where they combined direct swallowing therapy with another indirect therapy. And I’ll explain to you these indirect therapies are either brain stimulation such as transcranial magnetic stimulation or direct current stimulation. And in this case, just that was provided. In these kinds of studies which are 16 — so this is clearly where the field is going — they combined transcranial magnetic stimulation while the patient is doing therapy or direct current stimulation while the patient was doing therapy.

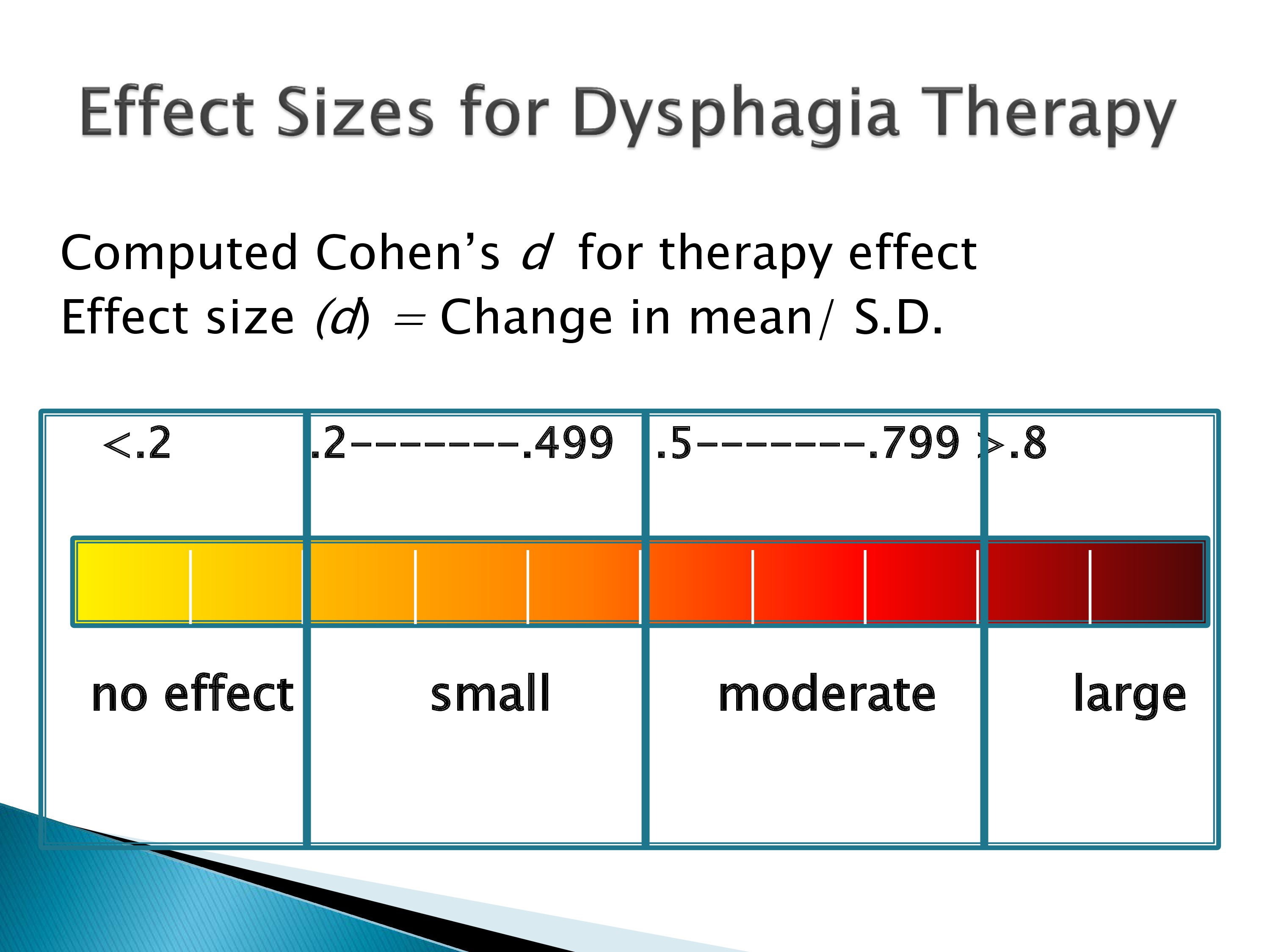

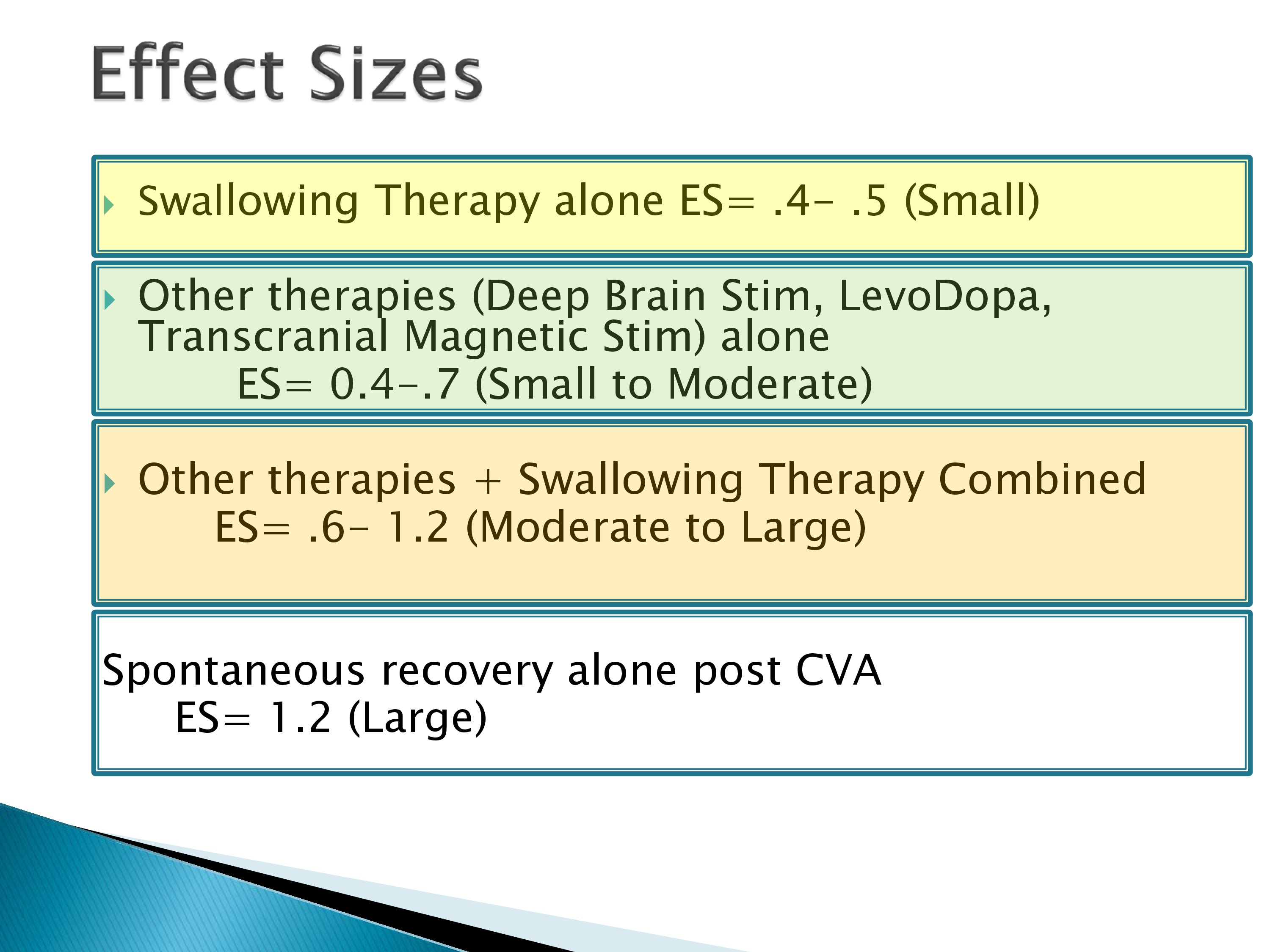

Well, we used their data and computed effect sizes. And if you compute the Cohen’s d, the general understanding is no effect is down at .2. You get a small effect between .2 and .49. A moderate effect between .5 and .79. And then a large effect size is something like .8 where it’s close to a standard deviation in the data that you’re getting a change of therapy or a treatment.

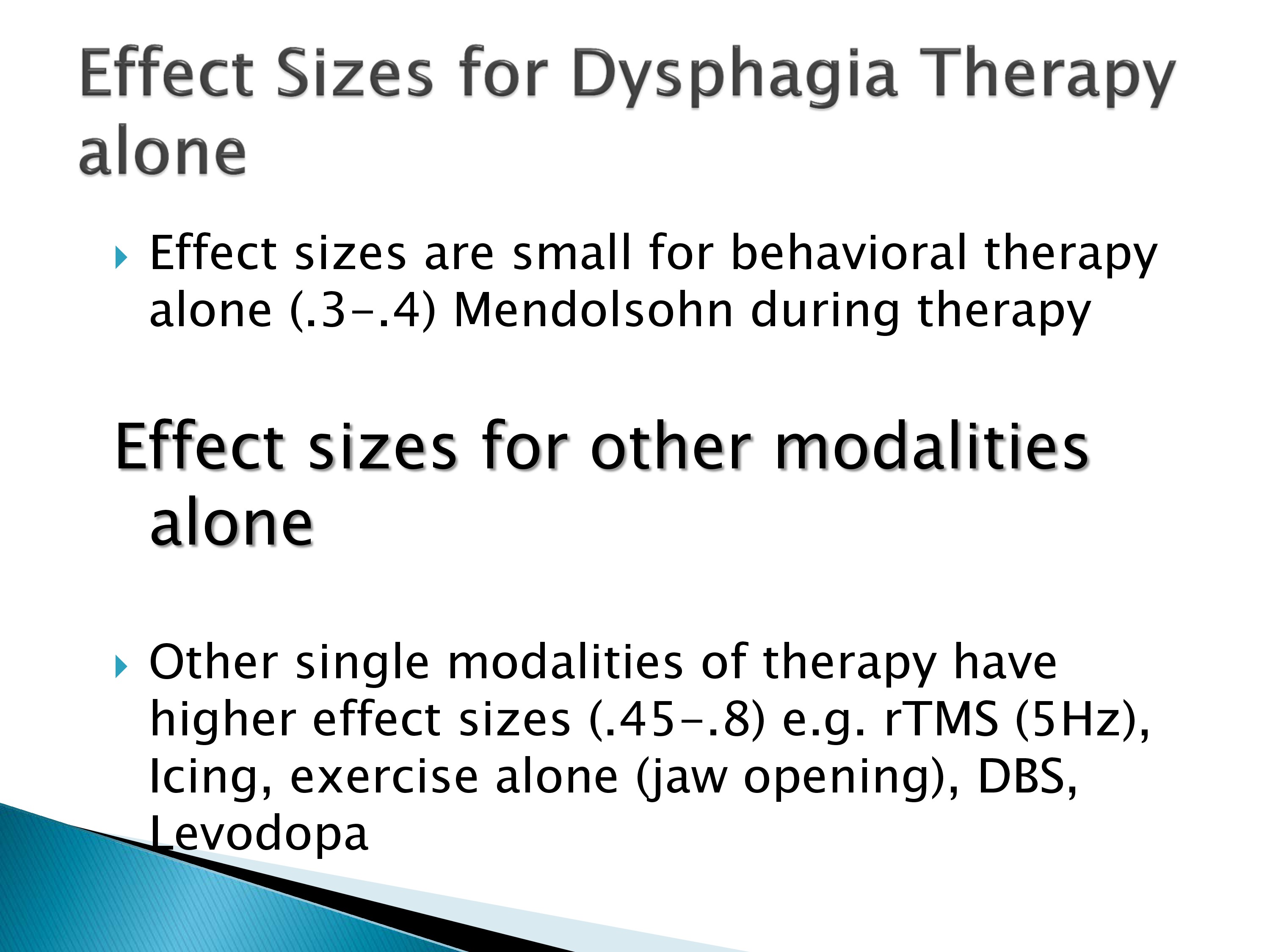

And when we looked over these random controlled trials, we found that the effect sizes for behavioral therapy alone were very small, .3 to .4. The effect sizes for other modalities were a little bit higher but not huge, .45 to .8. This is like repetitive TMS, deep brain stimulation, icing, or levodopa. And these had moderate effect sizes.

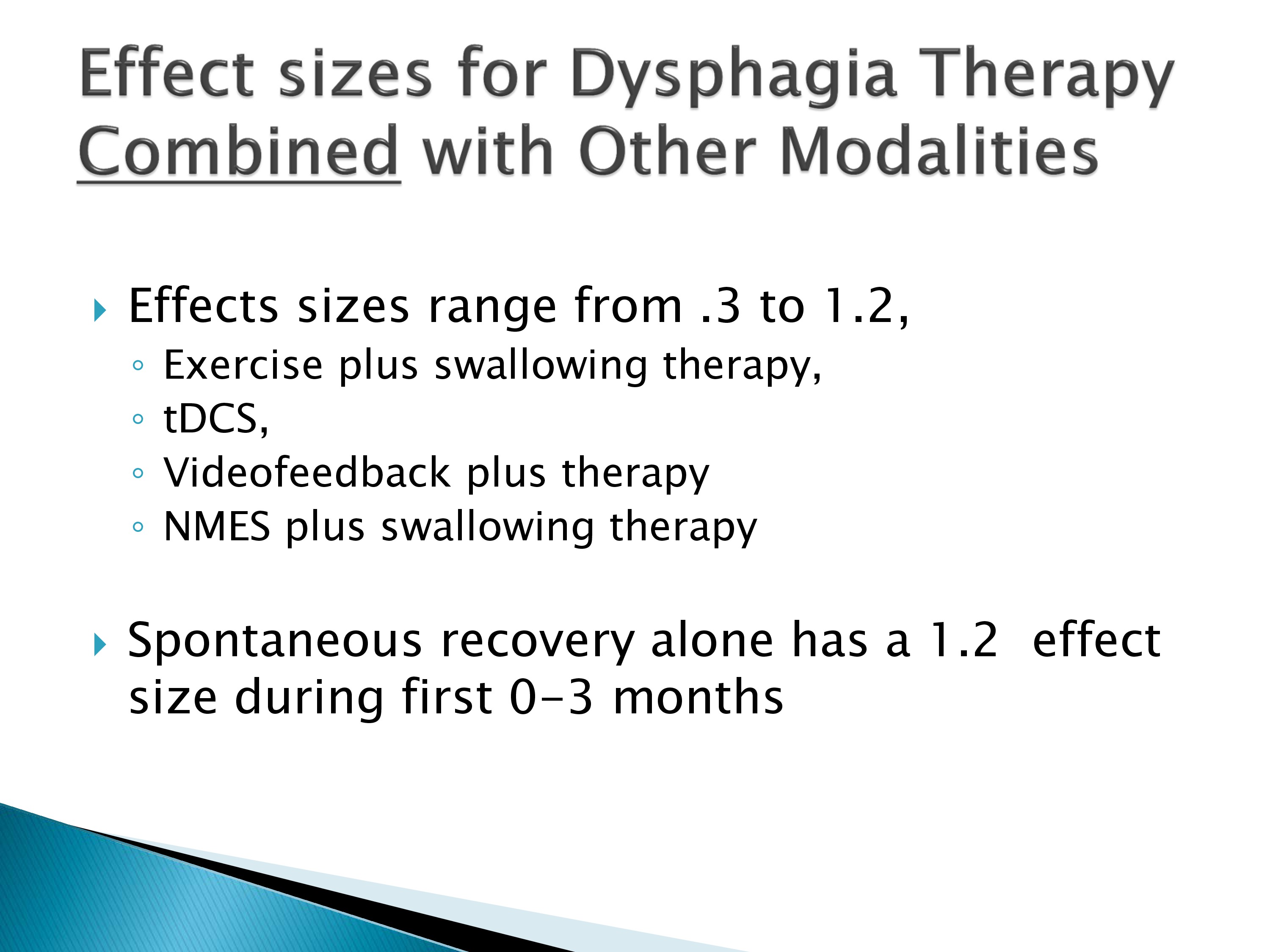

When they combined dysphagia therapy with these other therapies such as direct current stimulation, video feedback, or neuromuscular stimulation plus swallowing therapy, the effect sizes range some were low. Some were 1.2. But many of these were studies during the early recovery process in stroke, and you can see that in their sham group or the controlled group they had an effect size of 1.2 which is huge compared to the therapy. So it’s drowning out the therapy effect size.

So in this review we concluded that the effect sizes are not overwhelming. Swallowing alone was low. Other therapies alone were moderate — small to moderate and then combined therapies had a much better range but compared to spontaneous recovery, they’re not overwhelming.

So this suggests that we need to have optimized therapy before we do clinical trials so that we get the best that we can possibly can before we start comparing different treatments.

Methods for Optimizing Therapy

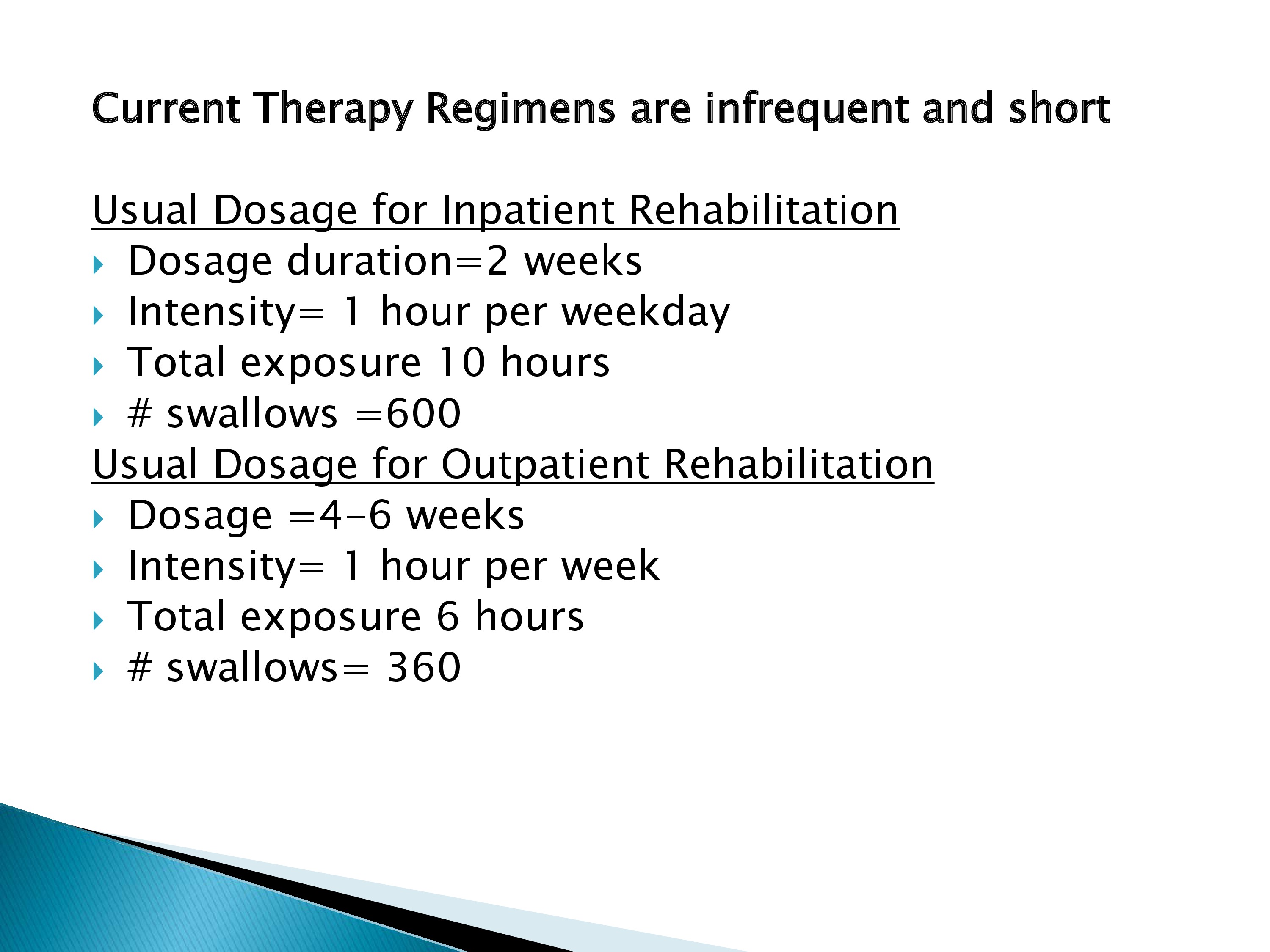

Now, in all of these studies, surprisingly, everybody used a very similar regimen.

They used an infrequent and short regimen in that the patient was seen 1 hour a day for 10 days or you know, the weekdays during 2 weeks. So that gave them a total exposure of 10 hours. During that time, they could do as many as 600 swallows.

Outpatient rehabilitation was even more infrequent and there, the dosage was — well, the duration of treatment was 2 to 4 but they were only coming in 1 hour a week. And had an exposure of 6 hours of therapy to try and change their swallowing.

So we need to consider other regimens to try and optimize the effects of our therapy. And one might be prolonging the therapy. Another by multiple sessions a day or shortening the therapy to avoid fatigue which is our adverse event. Combining other modalities while you’re doing the therapy as well.

Adaptive designs allows us to examine each one of those parameters and find out what would be the best way to deliver the therapy and what would provide the most bang for our buck, so as to speak. We need to find out how many trials a day a patient can do. What the most effective session duration. Why is an hour always used? Maybe some patients that’s too long. Finding the most effective treatment dosage in the total number of sessions.

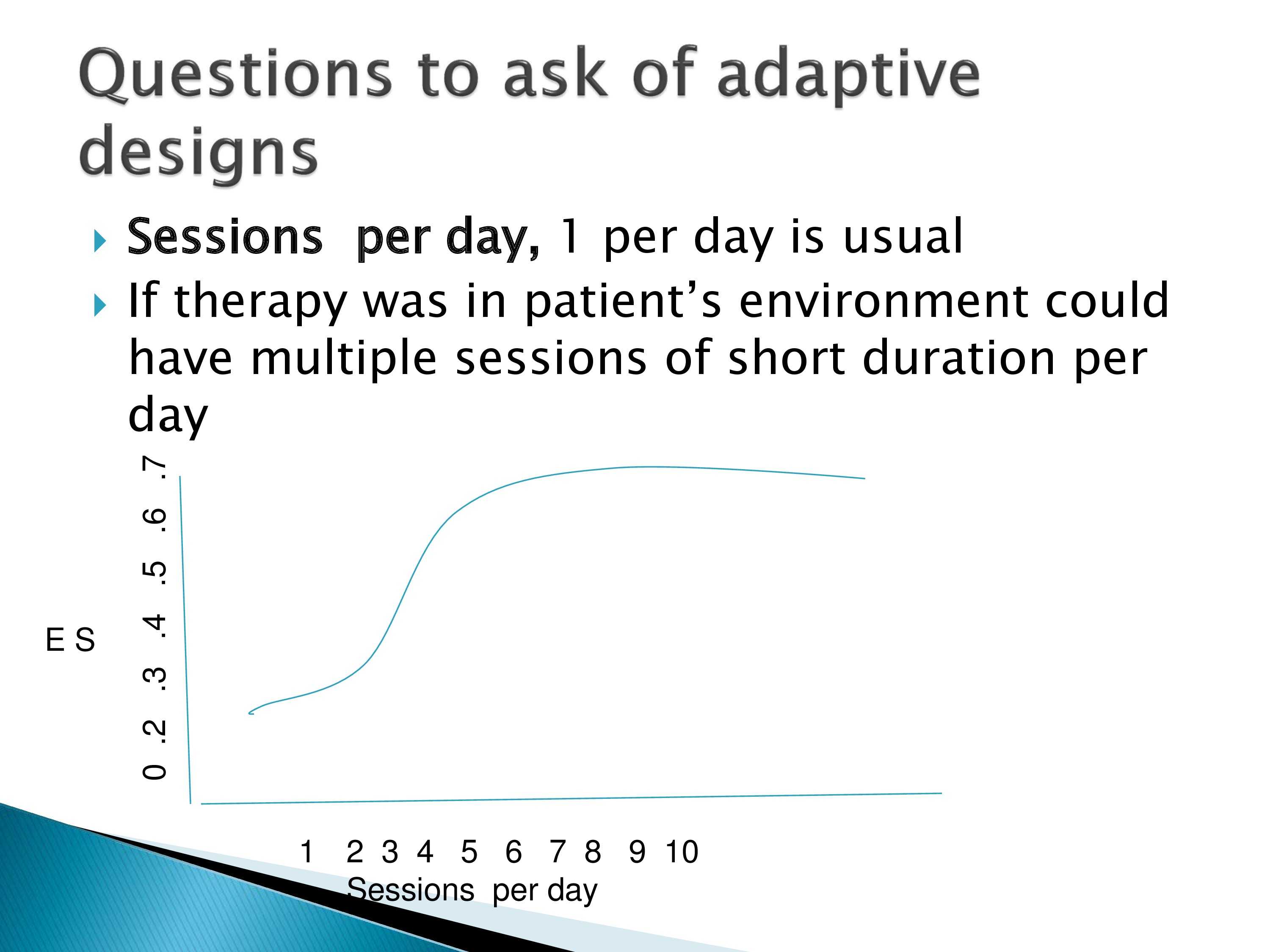

So we want to look at curves where we change, get the effect size for different numbers of sessions per day. Perhaps one session isn’t the optimum. Perhaps we need to do four or five sessions a day and we get a better effect size with that.

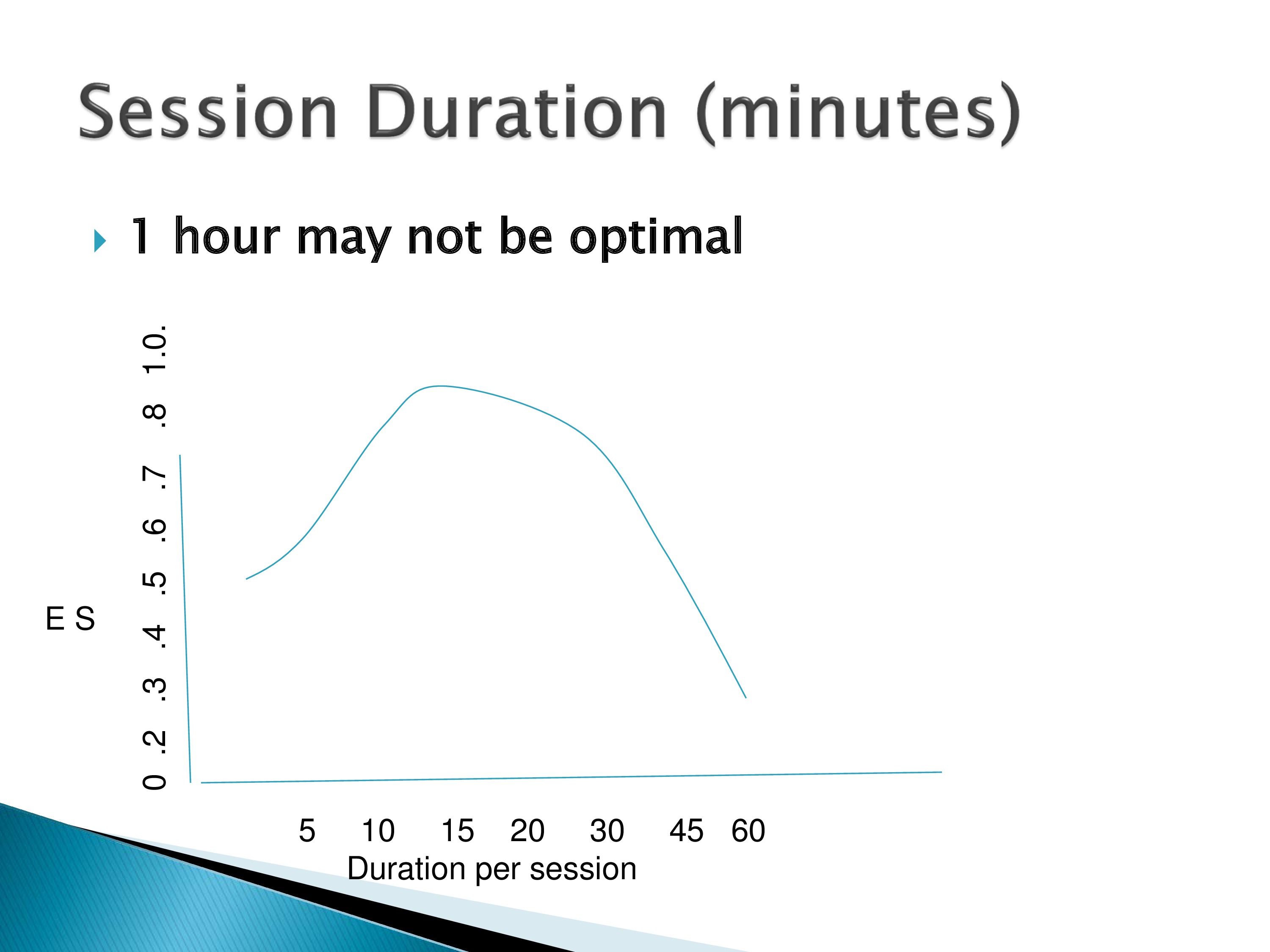

Another is the session duration. These are hypothesized curves. Maybe 15 minutes is better, 16 minutes is not. So we need to be able to examine those aspects.

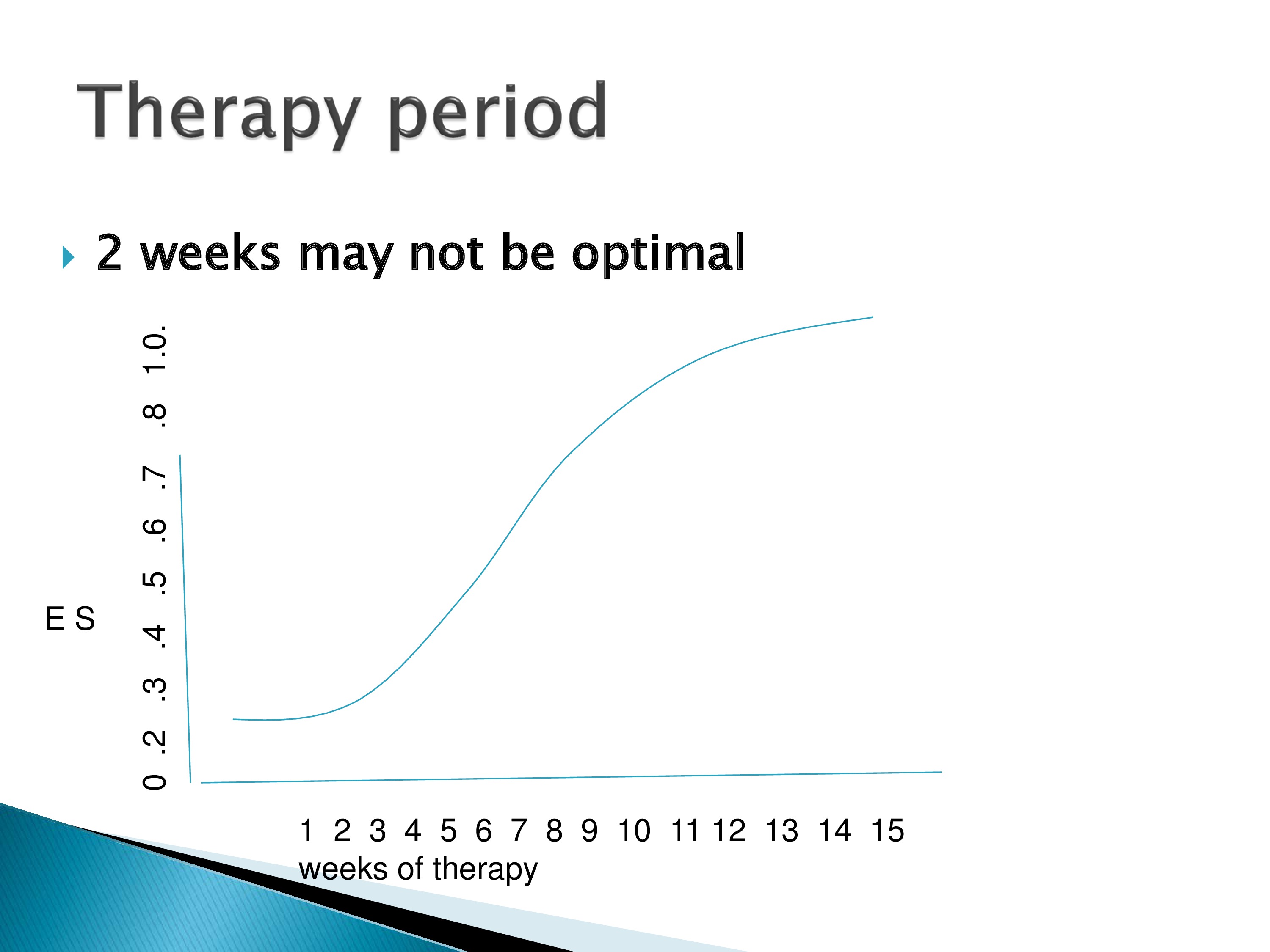

And then, how long should therapy be? Maybe two weeks is not best. Maybe we want to get further up on the curve and try and get a higher effect size for a longer duration of therapy.

So where would we use adaptive designs? Before we do the large random controlled trial. They can help us identify an optimum treatment regimen and avoid a costly lengthy RCT with a not optimal, effective therapy.

Maybe different regimens for different types of patients or different treatments for different types of patients and those can be examined as well.

But I should warn that all of this needs to be done very closely with a biostatistician, and we have invited Dr. Yeatts to present to us on this type of design and how it can be used. And she will help us translate some of this from what’s used in other areas of research for clinical delivery to our area.

Reference

Drulia, T. C. & Ludlow, C. L. (2013). Relative efficacy of swallowing versus non-swallowing tasks in dysphagia rehabilitation: Current evidence and future directions. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports, 1(4), 242–256 [Article] [PubMed]