The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

So thinking about implementation generally, what is implementation? Today, I’m just using the term as a construct to describe a lot of different types. But it is research that addresses complex, real-world variables in practice settings. And it does that by research that investigates barriers and solutions for the delivery of sustainable, effective protocols that will maximize outcomes for a large number of consumers.

It also is research that includes stakeholders. When I talk about stakeholders, I’m talking about practitioners, clients, caregivers, administrators, all of the stakeholder in that protocol that’s being delivered. Also, the other characteristic of implementation science is that it actively integrates research and practice. Actively. All along. That’s a slightly different model than talking about efficacy to implementation.

So implementation is about: how do you move evidence into practice? Or, how do you find evidence in practice? So thinking about those in both ways.

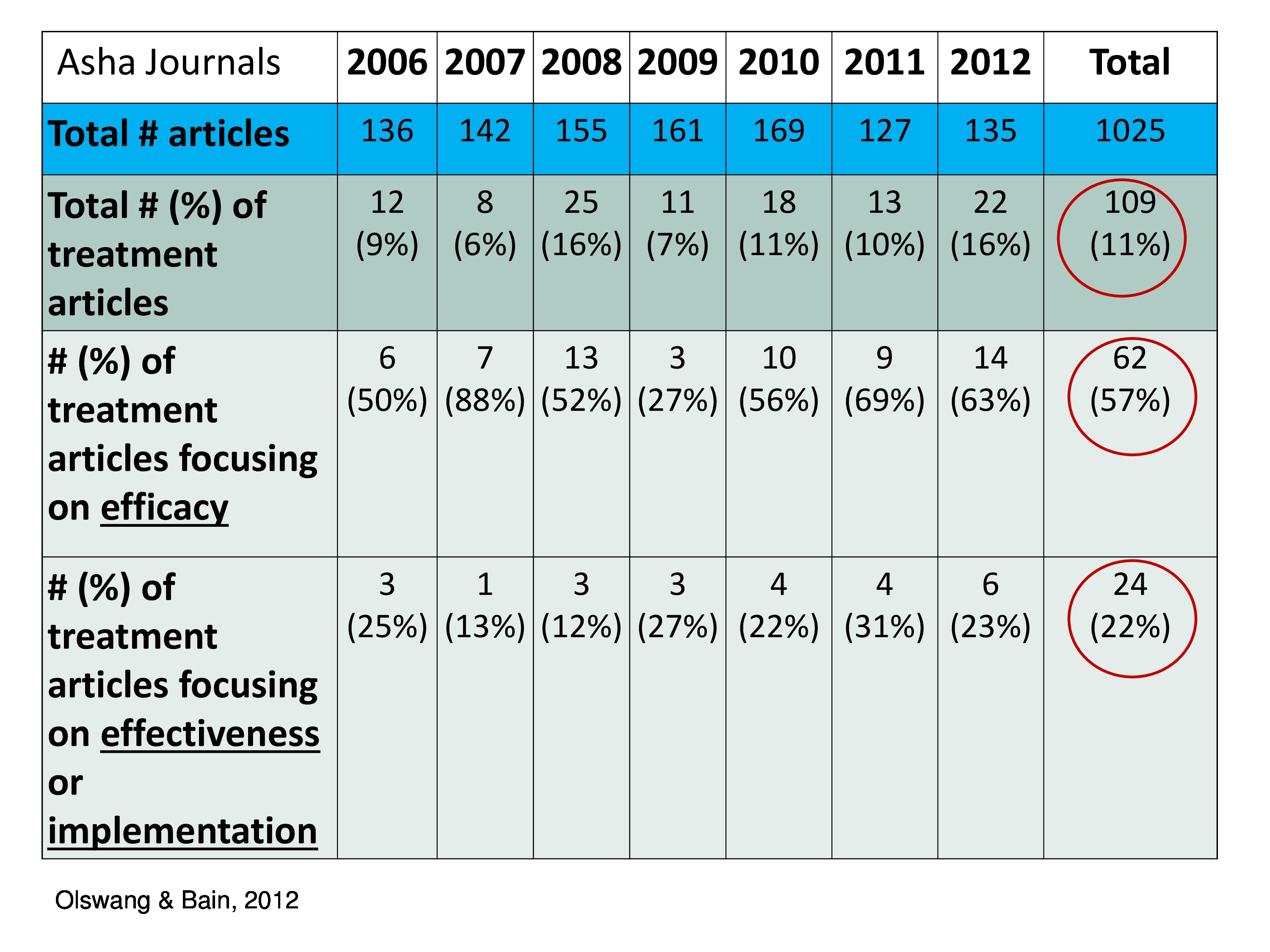

How have we been doing in our discipline? My colleague Barb Bain and I looked at, reviewed some journals — ASHA Journals — from 2006 to 2012. And we broke them up into these categories. So we have total number of articles. Then we have total number and percent of treatment articles. And you can see over these years that we have out of 1,025 articles — these by the way didn’t include letters to the editor, these were research articles. Out of 1,025 we had 109 that looked at treatment, so only 11 percent in our own journals.

What percent of the treatment looked at efficacy? Well, we’re doing pretty good. Those of us who have been doing research looking at intervention, treatment and these data — 57 percent were about efficacy. Not so good moving along the pipeline moving along the pipeline into effectiveness and implementation. Only 24 articles out of the 109 tackled that, only 22 percent. So as a discipline, we’re not really doing a lot of implementation — effectiveness/implementation. If we’re going to respond to the needs in healthcare and education and this new need to do business differently, we have to begin thinking about that.

So, this is just a little preach here, I’m preaching, that we really have to start thinking about a different way to think about our research. Maybe not different — an expanded way. Because we’re not throwing out the efficacy, but we’ve got to expand.

So, let me move on to my part about this. That is the applied researcher’s perspective.

I came back to get into research as an SLP. I was a practicing clinician. I was working in early intervention. What drove me back and what drove me to do research was this basic question: Am I making a difference? I was working with toddlers, young children, and I was thinking, what’s my work and what’s maturation? This is what drove me back to thinking about research. So my research always has this as its goal. My personal research. And my lab’s research and my doctoral students’ research.

So, what did I want to know? I wanted to have evidence about what to treat. How do you pick your treatment objectives? There should be evidence for that. When to treat? Then, how long to treat. Those are the basic questions as an applied researcher that I wanted to ask.

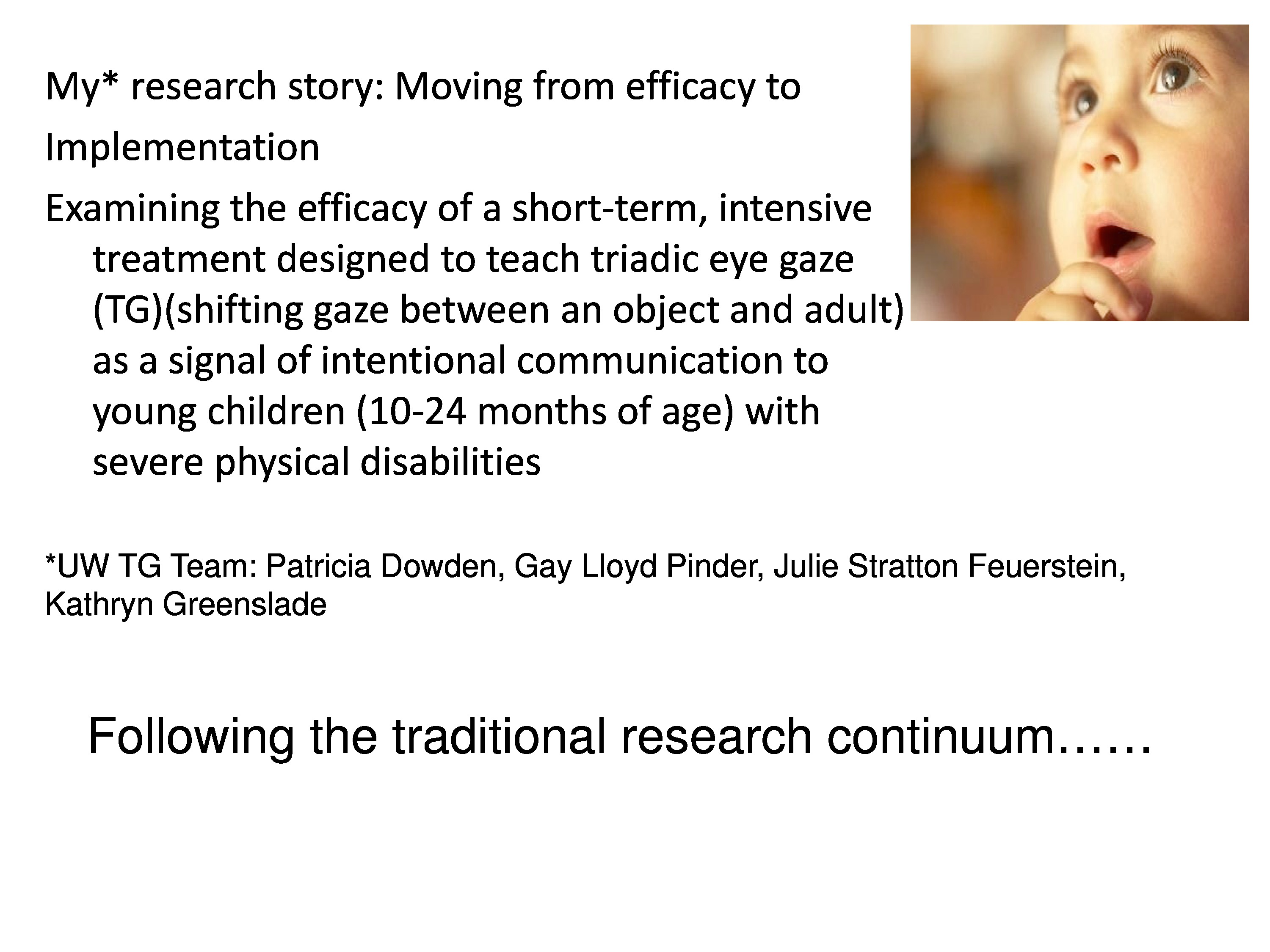

I want to use myself and one part of my research as an example, to illustrate to you the issue that I’m confronting right now about implementation, and what I’m thinking about and what my lab is thinking about. I say here it’s my research story, but it’s really my UW team (TG stands for triadic gaze) — Pat Dowden, Gay Lloyd Pinder, Julie Feuerstein and Kathryn Greenslade — that we’ve been working on these questions for many years. So, I’m going to talk to you about that.

Moving from efficacy to implementation, we’ve been studying a short-term intensive treatment designed to teach triadic eye gaze (TG) to young children with severe physical disabilities. And triadic eye gaze is looking from a person, to an object, back to the person. That connection that has been shown in the literature to be the hallmark of intentional communication, linking together the object and the person.

We’ve been embarking on this research to look at a particular treatment we developed and to take it through this research pipeline, the traditional research continuum.

So, it started in the 1990s. We did two feasibility studies in the 1990s. The first one was a time series, single-case ABA multiple baseline across contexts study. And, yes, we showed our treatment did create change. It was very promising. This was a work with Gay Lloyd Pinder and Kathleen Coggins.

We went on to do another feasibility study, this one was a little more sophisticated. It was a time series study, ABA, multiple baseline across contexts, but now we’re replicating across three children. Again, these are children with severe disabilities. These are children who are characterized by sensory motor, perhaps cognitive deficits, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, other syndromes, so these are very severely impaired babies.

With all of these studies, these feasibility studies, we had a single SLP who is delivering this service, this child-focused treatment, directly to the child — caregivers observed — two times a week, for 15 weeks. It was in the clinic, we had outcome measures one time a week. Efficacy research. Systematic, well-controlled, and saw nice responses to the treatment and replicated across the three children.

We then went on to do another feasibility study, and this feasibility study was another time series, a multiple baseline study, but this was across caregivers. We wanted to see if caregivers were involved in delivering this treatment, how did they do? There was one SLP, but this time the SLP was treating the caregiver, not the child, two times a week. This was a controlled length — three weeks — and we had outcome measures.

This study showed that we could teach caregivers part of the protocol. We were really successful with part of the protocol, but not all the protocol, which was interesting. And the children responded to the parents, and the children showed some change but not as much change as when the SLP delivered the protocol.

So here we are, three studies done in the 1990s, and into the early 2000, and we’re having good evidence to show to continue this path of research.

Then we were fortunate to be involved with a project with folks at the University of Kansas, and we were able to conduct a randomized controlled study — this was from 2006 to 2012. I just wanted to put here that we had 46 children and families who consented, but ultimately, we had 18 children who met our criteria, who were able to stay in the study, their parents were able to stay in the study. So this is not easy research to do. And already now we’ve got over a decade of work that we’ve done.

Nine children in our experimental group and nine children in our control group. The experimental group got our triadic gaze treatment, that focused, intensive treatment given by the SLP plus their standard of care. Then the control group got only their standard of care. Now we have three different clinicians, so we’ve trained a variety of clinicians. We’re expanding our study into something that’s more like effectiveness moving down this pipeline. We also have a different SLP collecting the measurements. And the treatment was done in the homes, but still twice a week for 16 weeks.

As with the feasibility studies, we found very promising results we had greater changes in our experimental group than our control group. We have identified a treatment that is showing great promise. We are eager now to begin thinking about how do we get this out there, how do we begin thinking about how treatment might change for birth to three. Children in this young age group. Again these are babies, 10 to 24 months, I’m not sure I said that. It’s on the slide, but 10 to 24 months, seen in birth to three centers, and it’s a model that is a little different than is often done in birth to three because right now in birth to three there’s a lot of naturalistic, there’s a lot of coaching that’s being done. And we’re advocating and we’re demonstrating the effects of an SLP-delivered child focused intensive treatment. And our belief is that this intensive treatment, teaching intentional communication through eye gaze, can kickstart the child into moving forward.

We’re advocating a service delivery model that’s a little different, and a treatment that’s a little different because oftentimes in babies with physical disabilities the SLP is not the primary service provider, but the PT and the OT.

A lot could be different and that’s where we are faced now with our challenge. How do we move this into practice? How do we move it into birth to three centers?

The challenges are, to name a few, include understanding the intricacies of service delivery systems in birth to three centers. Including — these are some of the challenges and the intricacies:

- The needs and priorities of the stakeholders. That is the organization, the administrators, the practitioners, the children, and the families. Here we have this really good protocol, and here we have the birth to three centers and what are their needs and priorities.

- The constraints of the real-world logistics that influence how we train. We have a nice protocol but now we need to train practitioners. What are the constraints for implementing that? Then we wish to get, of course, implementation fidelity, having it done the way we’ve been doing it. And sustainability — or stability over time. All in this new context.

- And outcome measures. What are the appropriate outcome measures and are they sensitive to different phases of implementation, and different stakeholders.

These are the questions that our team has been thinking about. Can the treatment be implemented as designed? What adaptations need to be made for the birth-to-three center? What type and degree of training are required? What kind of training works best with the needs of the birth to three center? And how does buy-in of practitioners/administrators influence the outcomes. Are they equally as excited to have our protocol as we are to share our protocol? Those are some of the questions.

We are moving forward with this effort. I want to leave you on my part with the challenge and the thoughts that I have. And that is, moving into practice is every bit as scientific as efficacy research. And there are variables to control, there are variables to investigate. You can’t just write your article. You can’t just give a workshop. There is more to it. There is something more proactive in terms of the research that you’re doing to prove and to demonstrate that you can do this with fidelity and sustainability.

What I want to leave you with is this question that keeps sort of haunting me, and that’s prompted me to be an advocate of implementation science and to begin thinking about it and having our doctoral students think about it, our new investigators think about it. That’s this question: If I would have been thinking about implementation when I designed my first feasibility study, or my second, would I have designed it the same way? Or would I have had my stakeholders be more involved. Because right now I still have this gap between our treatment protocol and implementing it for birth to three. So this question is what’s really prompted me to be excited about having myself and our team and everyone in this room think about implementation science earlier rather than later.

References

Pinder, G. L. & Olswang, L. B. (1995). Development of communicative intent in young children with cerebral palsy: A treatment efficacy study. Infant-Toddler Intervention: The Transdisciplinary Journal, 5(1), 51–69

Pinder, G., Olswang, L. & Coggins, T. (1993). The development of communicative intent in a physically disabled child. Infant–Toddler Intervention, 3, 1–17

Olswang, L. B., Pinder, G. L. & Hanson, R. A. (2006). Communication in young children with motor impairments: Teaching caregivers to teach. Seminars in Speech and Language, 27(3), 199–214 [Article] [PubMed]