The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Getting that all-important academic position. The good news is that in communication sciences and disorders, we’re quite different from most other fields. Very often, because of the small PhD generation in our field and the relatively high demand, there might be 6-8 applications for an opening. Sometimes even fewer than that. If you want to find, for example, somebody for a faculty slot in motor speech disorders, good luck if you can get 4 applicants. It’s not easy to do. That’s true even in some of the traditional areas of communication disorders. Stuttering, language disorders. We are not turning out enough PhDs to replace people like me who have retired.

So, the good news is there are a number of positions available. Which means there is a very high likelihood of finding a position. There are variable opportunities for teaching specialization. You might have to be flexible. It’s not very often you’ll find, for example, that you will get to teach in just one narrow area. You might be asked to teach in other areas because it’s impossible for most departments to dedicate one faculty member to each specific area like fluency or voice or swallowing, and so forth.

What do you need? Well certainly, an important area of expertise. Something that you can say, I’m really the expert. When I was in grad school I used to be told that when you’re done with your dissertation, you should be one of the world experts in that area, and you should be able to claim your expertise.

You also should have a willingness to teach in other areas, again, to buttress your desirability as a faculty member.

For some smaller programs you will need to do clinical training along with research. Some programs in our field cannot afford to have people who do only research and teaching. They might also have to participate in clinical supervision. That’s a two-edged sword. It comes with opportunities, but it comes with certain burdens, and it’s a critical question of balance for many people.

How to Prepare

What you must prepare. A job talk. This is extremely important. Sometimes I think we don’t really help students appreciate the importance of a job talk and to appreciate the art and science of a job talk. There’s really a lot that goes into it. I’m surprised there aren’t more articles that say, “You’re going to give a job talk, here’s what you should consider.”

It is absolutely essential to rehearse, rehearse, and rehearse. If you can do so, prevail upon your friends and others — your enemies — and give your talk before them. Get feedback. Find out what works and what doesn’t work. Because this is going to be one of the things that leaves the strongest impression during your interview. You’ll meet a lot of people. But there’s one point when you’ll have an audience sitting in front of you, and you want to really convince them this person if very knowledgeable, this person is a good communicator, this person I would like to have as a colleague.

Develop long-term goals. At least 10-year goals for research and career development. For a position that requires teaching along with research, develop a statement of your teaching philosophy and goals. If you’ve never tried to do that, it’s a good exercise. What do you admire about the people you met who are good teachers? What did they teach you about this strange craft of teaching? And what kind of philosophy do you think you would like to have as a teacher. Something that ideally would sustain you for decades of teaching in the classroom and being a mentor.

A research plan for the first five years is very important. It doesn’t mean you have to follow that. It’s not like a contract. But it indicates you are thinking ahead. You have a vision for what you want to be, you have a vision for the research plan as it unfolds. And it should, ideally, have a sequential nature. You could say, “You know, the first three things I need to do are these, because it’s going to establish these fundamental principles.” These will, in turn, lead to other areas. If you’re interested in clinical research, you might say, this is the first kind of thing I need to do because I think it’s going to have a lot of impact in the formulation of a clinical intervention. Then have follow up plans to demonstrate that it really does succeed in what you hoped.

Very important, this is another area that we don’t really prepare people well enough. When you go to a job in academia, you should walk in within your hand a start up package, what you need. You should have a pretty good idea. And don’t be super conservative. You should not feel embarrassed or modest. You should think on the order of — I’ll say it — $100,000. That’s a target figure, you’r not going to get that everywhere.

But when you’re starting off in a career, that university is making an investment in you, and the start up package is a sign of their commitment to your career. It gives you what you need to get a laboratory started. If you don’t get $50,000, don’t feel bad, but at least bear that in mind as a typical starting figure for many departments of communicative disorders. If you’re in chemistry, it’ll be a million. So communicative disorders is a bargain in academia. Because our people will often start somewhere between $50,000 to $150,000. When I say $100,000 and you have in mind a $200,000 lab because you are doing some work in cortical processing, go for $200,000, don’t hesitate. But make sure that you’ve justified the items. Have an itemized list and be sure you can defend every item in terms of its entire package, and in terms of each component. So do some shopping. Walk in, so that when they ask you, “What do you need for equipment?” you say, “Oh, I’m glad you asked. Here it is. If you have any questions, let me know.” Be willing to negotiate. But be sure that you have a firm idea of what is needed to get your research underway.

Your CV should show increasing independence that is demonstrating you are ready for a faculty position.

Why is a research plan important? Generally it is required in employment applications as one of the “Big 3” — your CV, your research plan, and letters of reference. Share you research plan with the people who are going to write letters of reference for you. They should know you not only from your past experience, but they should have a sense of your research goals. Formulate that carefully. Have it read by friends, have it read by faculty and colleagues. This provides a road map of your scientific career. It shows what you have done, and what you hope to do. This is essential as a personal statement of your preparation and your goals.

When applying for a faculty position, the research plan is typically accompanied, again, by a statement of teaching experience, interests, and philosophy.

What to Look For

When you look for a faculty position, ask: do they have good facilities or good prospects of getting them. Get it in writing. In my career, unfortunately, I’ve had many people who took a job with the oral assurance from a dean or other person that they will get a laboratory space and they will get equipment. Never accept that. Always get it in writing. Get it in writing before you accept the position. It’s not that everybody is dishonest, it’s that crazy things happen everywhere. And fiscal emergencies can sometime interfere with the most sincere endorsements and assurances.

It’s a good idea to judge how faculty interact within and outside the department. Try to determine if you will be protected from committee work while you work on your tenure. It doesn’t mean no committee work, it means you shouldn’t have an excessive burden of committee work.

Will you have an advisory or mentor team. Increasingly common nowadays are teams of mentors to help junior faculty get through the hurdle of tenure.

Start up funds and laboratory facilities, and what are the funding expectations.

Guidelines for New Faculty Members

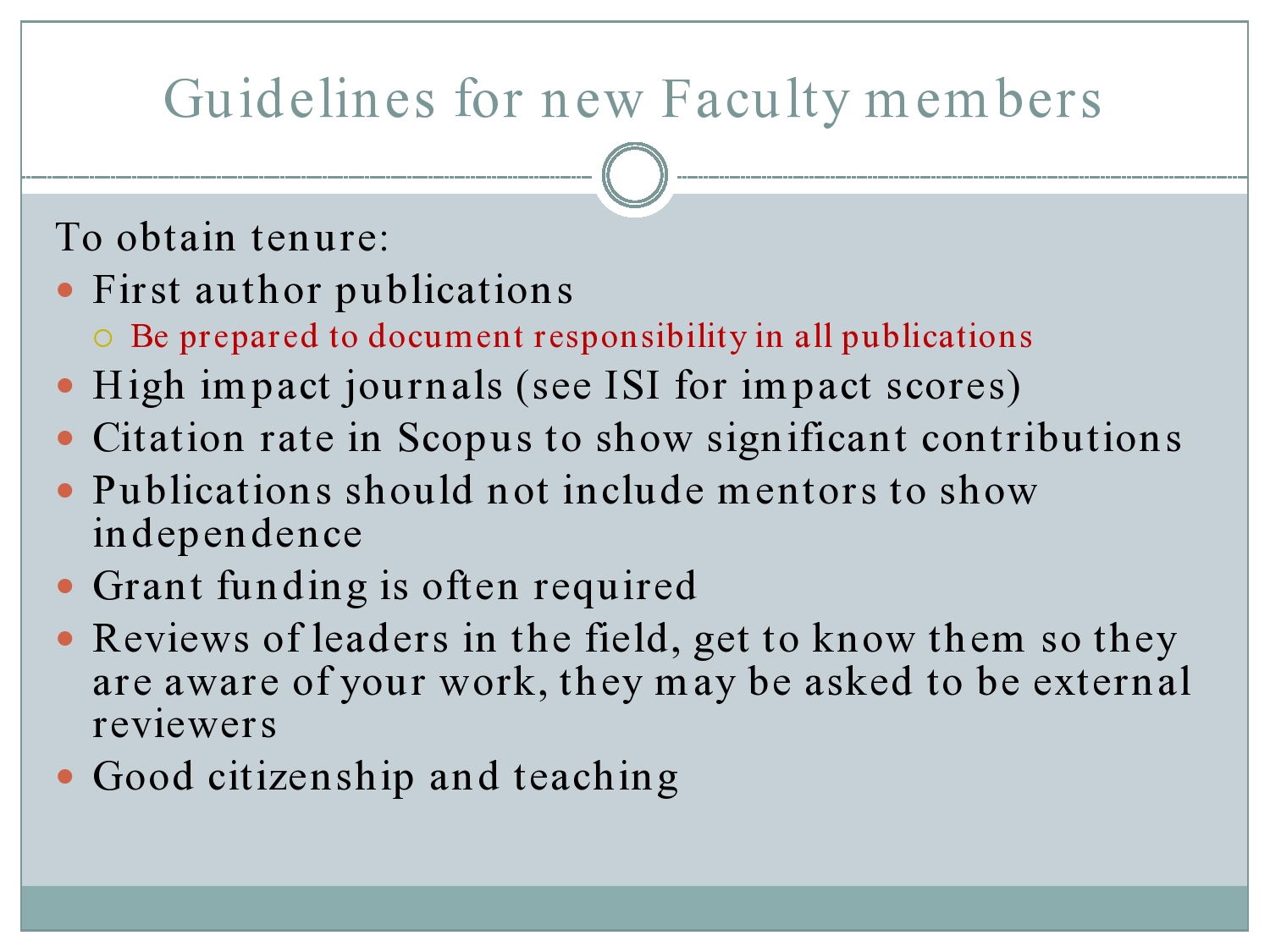

And guidelines for new faculty members, or suggestions. First author publications — be prepared to document your responsibility. Increasingly universities require that when you go up for tenure promotion committee review, you can indicate what role you played in every publication. Write that down, and make sure that your coauthors agree. Have an understanding of what did you do. Was it data analysis? Was it writing? Was it all these things?

Look for high impact journals. You can look at the ISI for impact scores. Look at the citation rate in Scopus to show significant contributions.

Your publications should not include mentors — not all the time — because you want to be freed of any apparent reliance on one individual. Grant funding is often required.

You want the reviews of leaders in the field, so it’s important they get to know you.

And demonstrate good citizenship and teaching.