The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

I’m going to start off with a quote from an occupational therapist, Carolyn Baum, that I really appreciate. She wrote as part of a Coulter Lecture that she gave a couple years ago about the notion of participation.

She said, “I still meet rehabilitation professionals who believe that people can put their lives on hold until they’re recovered. A focus on participation challenges us to find ways for people to do things that they need to do while they recover” – and I like this part, I think, the best – “Participation itself may foster this recovery because it brings the focus to motivation, competency, self-efficacy. All of these are psychologic concepts that are known to support growth and plasticity.”

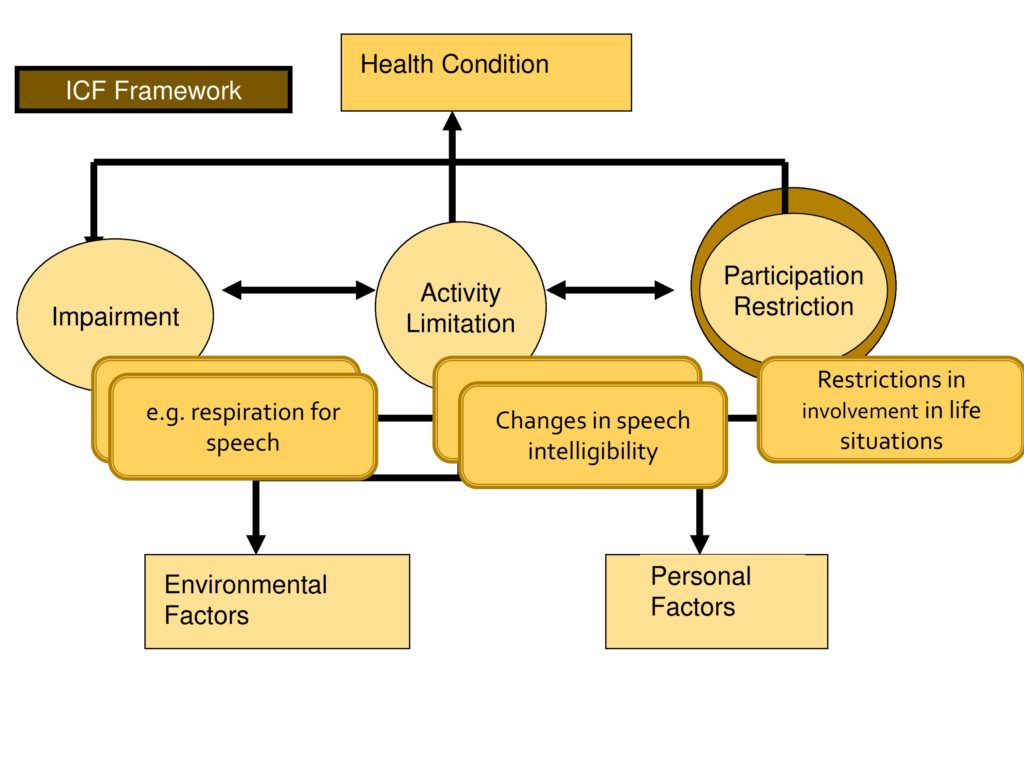

So it’s not just the end product, enhancing participation may go leftward on the ICF and enhance other aspects of recovery.

Another way of saying this is, “If intervention does not address the social aspects of communication, it may succeed in the narrow setting of the therapy room, but fail to bring about changes in the lives of people with motor speech disorders” or aphasia or other of our conditions that we work with.

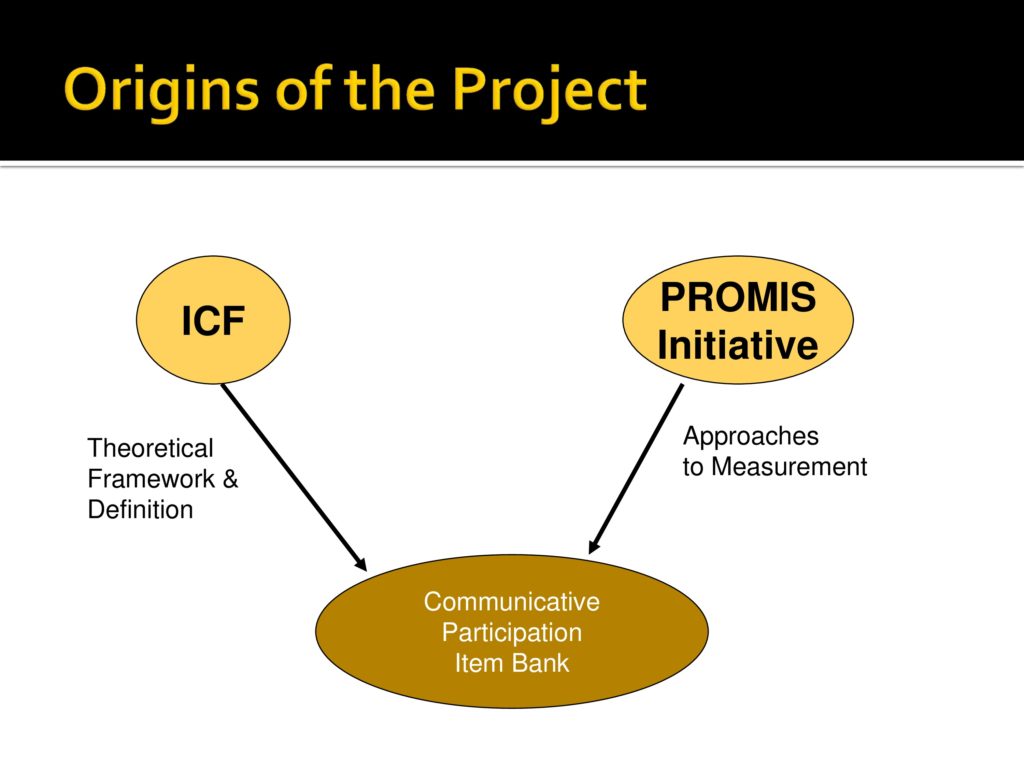

This is going to be looking at the last, really, almost 10 years of work in this area and we started off in about 2003, like Linda did, appreciating the need and the unique properties of the ICF, and that gave us the theoretical framework and definitions.

We were lucky enough at that time, also in 2004 I believe, Dagmar received her initial PROMIS grant, which brought the expertise in measurement to our group, and these two things happened at the same time and it was wonderful. Not preplanned, but wonderful.

I’m very lucky here because Karon has done such a wonderful introduction to PROMIS that I won’t belabor at this point, but PROMIS stands for patient reported outcome measurement, and it is intended to help develop a set of measures for things that are not measureable directly. A wonderful idea that you have to ask people how fatigued they are, how much pain interferes, what their level of self-efficacy.

It also depends on the World Health Organization, the ICF framework and I’ll apply it in the area of motor speech disorders because that’s my area, where impairment is changes in structure and function.

In motor speech disorders we do a wonderful job of measuring the components. We know how to measure respiratory support, vocal fold functioning, a lot of different features. We do okay at the level of activity limitation where speaking is an activity, and we measure that with things like changes in speech intelligibility.

We do a much less adequate job measuring participation and this is what really spurred our efforts in this area.

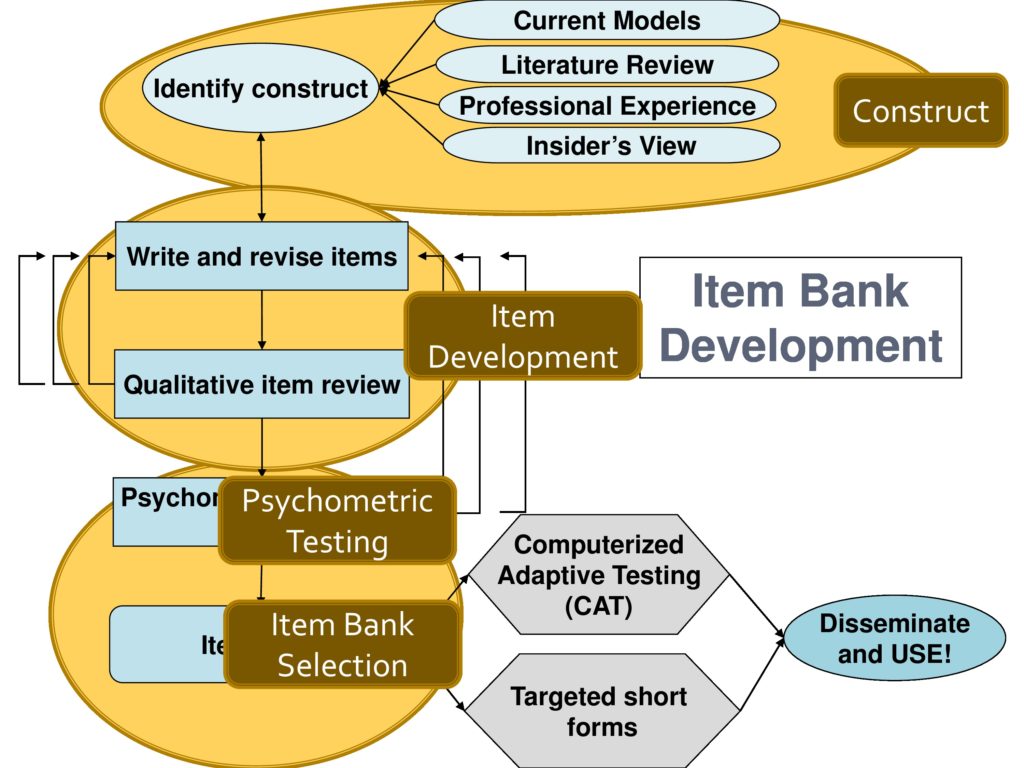

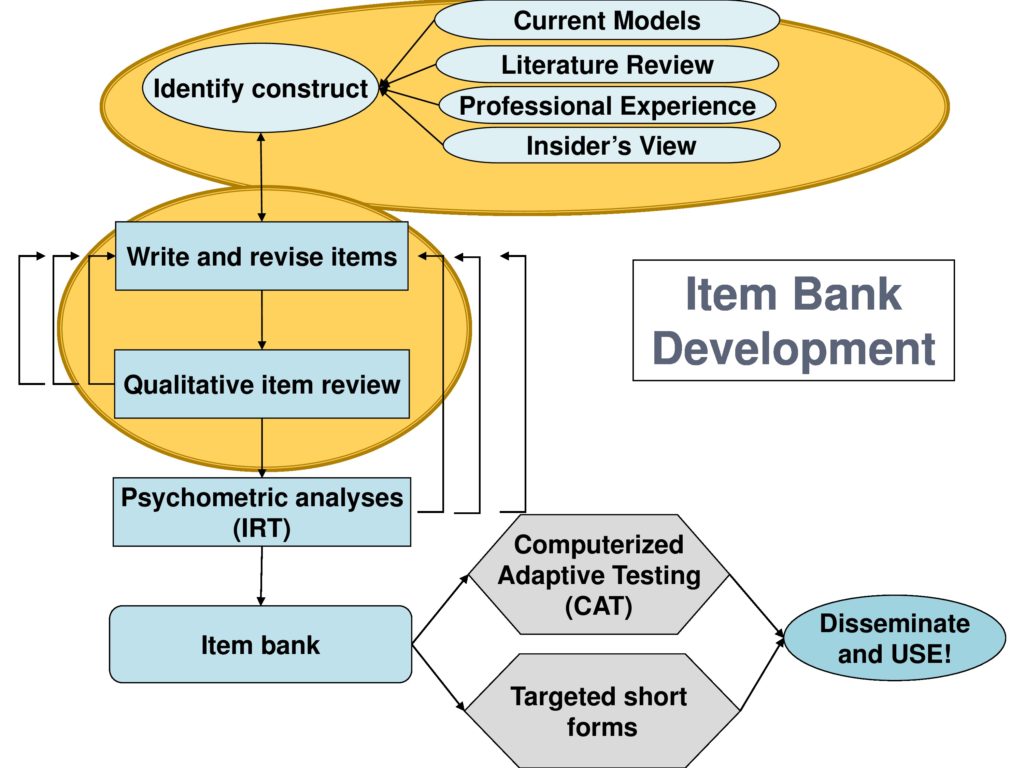

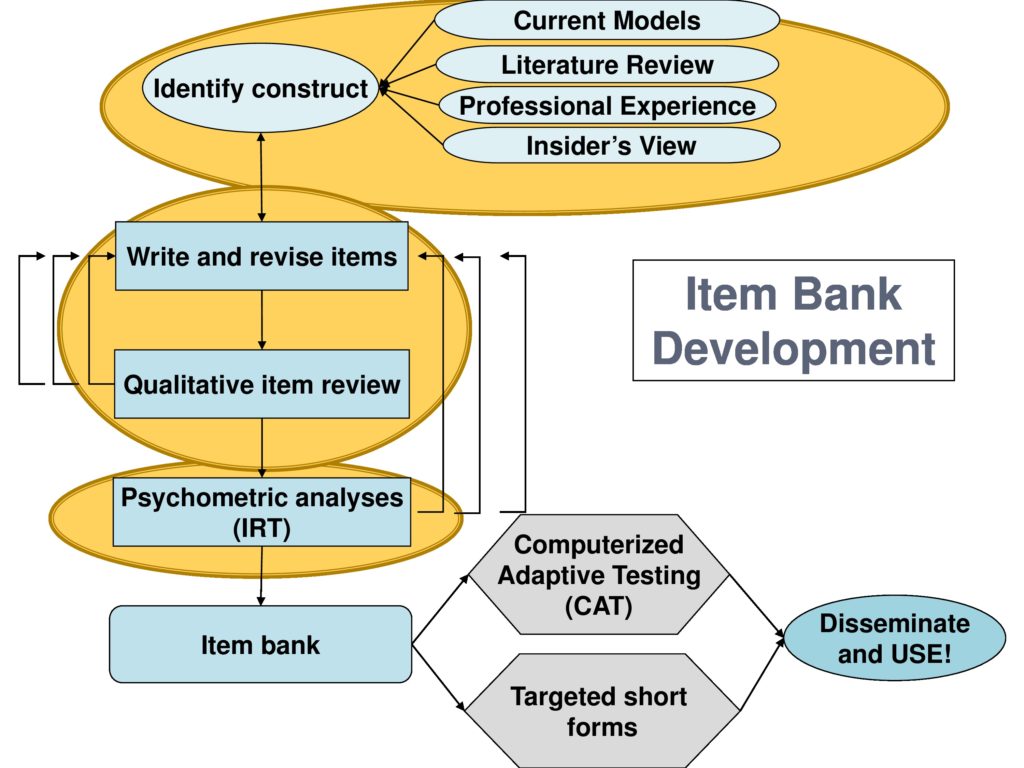

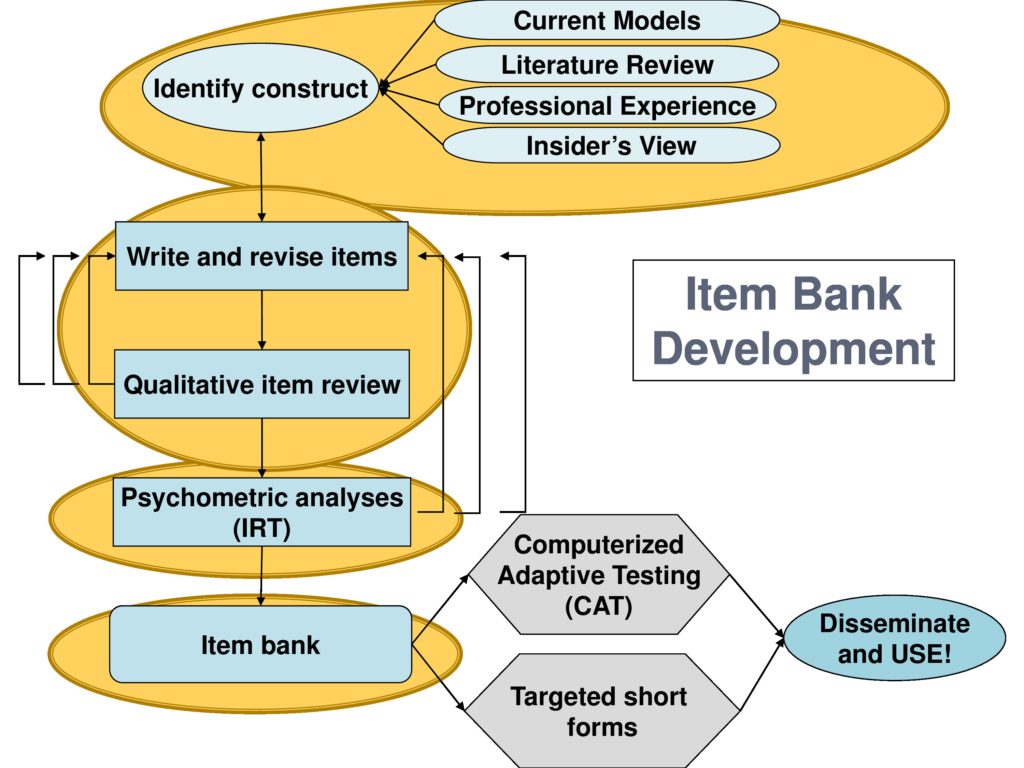

And this is an outline of my presentation and we’ll walk through it and again, this comes from Dagmar and the PROMIS people. These are the steps you need to go through in item development where the first thing you need to do is to identify the construct. And Karen is right that if you don’t spend enough time on this you will not succeed.

I remember in 2003 when we were writing the initial planning grant, Dagmar said well if you want to develop a measure, it will take you 10 years to do it and I laughed and said, “Oh Dagmar, you don’t know me. I do things quicker than that.” Well, I might’ve beat her by a month or so, but it really has taken 10 years. So you struggle with identifying and specifying the construct.

Then I’m going to talk about how you write the items and refine the items and this is really an iterative process where you do your best to write a set of items, you test them, you find flaws, you retest them.

You do psychometric analysis is the next step to throw out the items that don’t behave well.

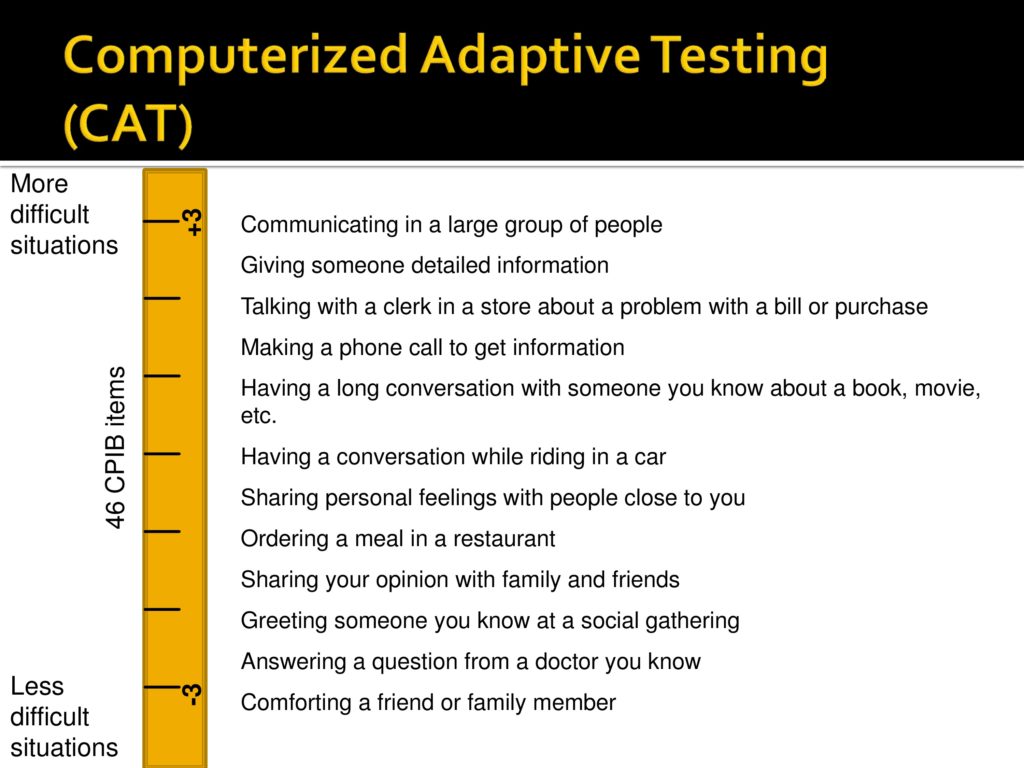

You develop an item bank which then can be used to either construct short forms or to do the CAT, computerized adaptive testing.

And I’m going to talk about these areas as a construct, the item development, psychometric testing, and item bank selection.

And I’m going to use this little convention here across the top to kind of keep you in tune with the part of the process that I’m talking about.

Identifying the Construct

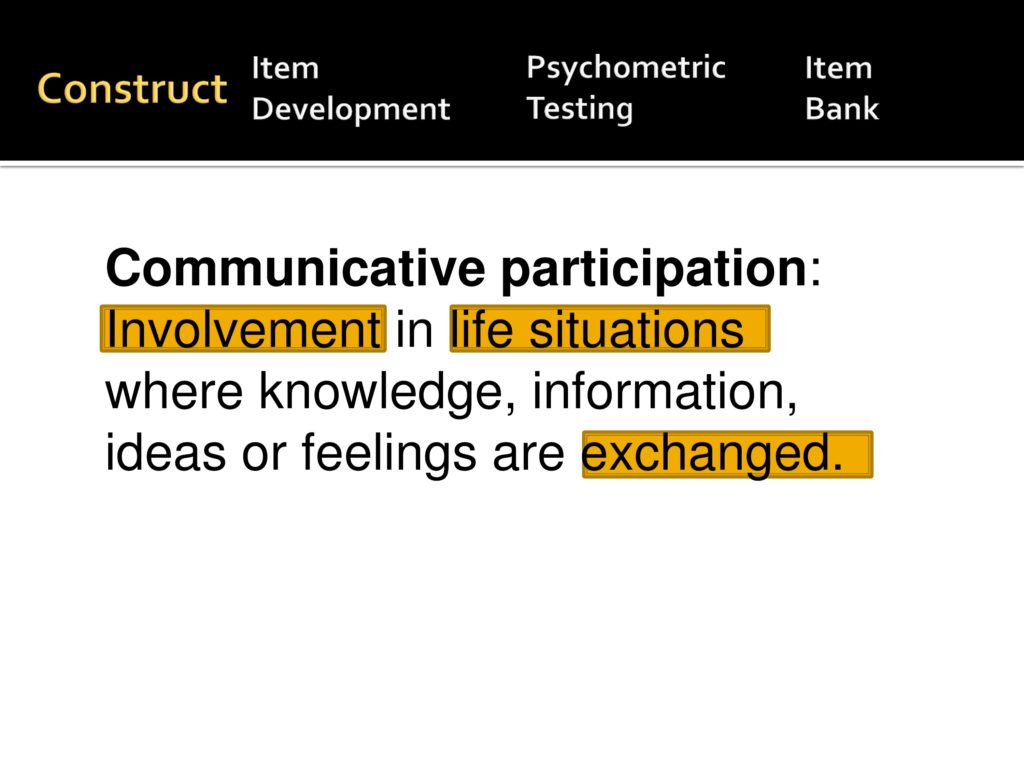

So we’ll start with the construct definition and the construct definition really draws heavily from the ICF where we’ve defined communicative participation as involvement in life situations where knowledge, information, ideas, and feelings are exchanged. And those three highlighted words are very important. It has involvement literally if you look it up in the dictionary is translated as to be occupied absorbedly. So you have to be invested in the activity.

I want to convey the concept of life situation, so it’s not in structured therapy tasks. Communication, I think, is unique because there always has to be someone else involved, it has to be an exchange. Communication involves at least two people.

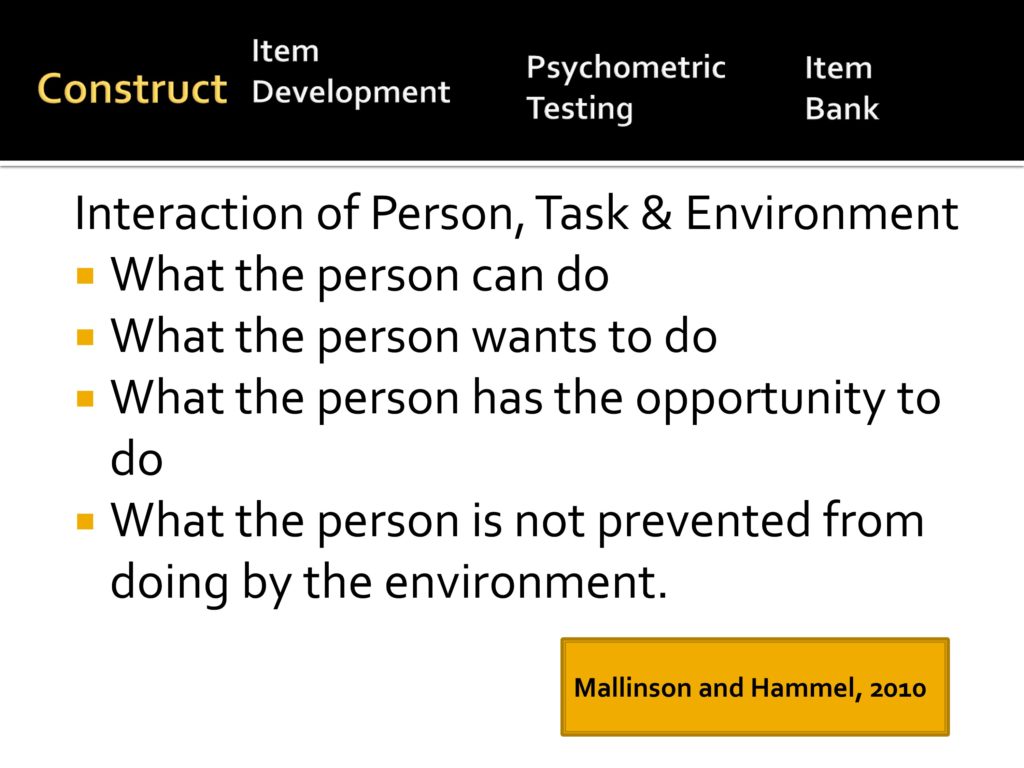

So drawing from more general rehab definitions, participation is really the interaction between person, task, and environment: What a person can do, what a person wants to do, what a person has the opportunity to do, and what a person is not prevented from doing by the environment. So it’s a kind of convergence of those.

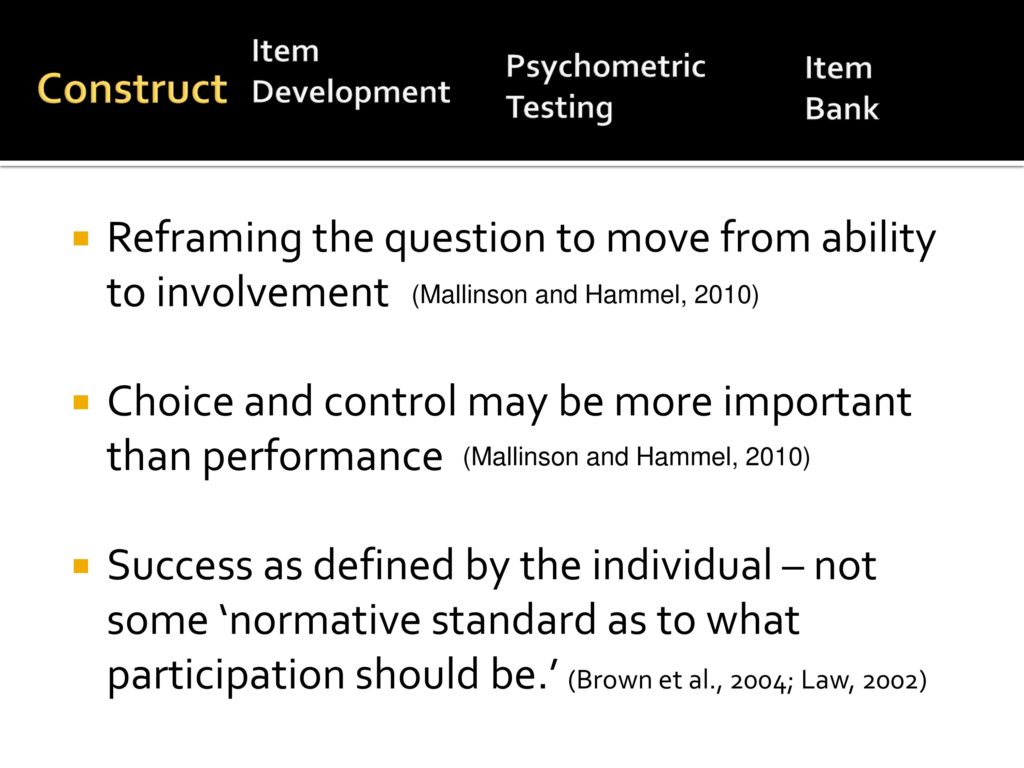

Again, from the more general rehab population, in this project we’re moving away from framing questions related to the ability to framing them related to involvement in life situations. We believe that choice and control is for our purposes may be more important than performance and that success has to be defined by the individual, not some normative sample of how much you should communicate.

Item Development

So back to our model. I’ve just talked about developing the construct and let’s move onto the item development.

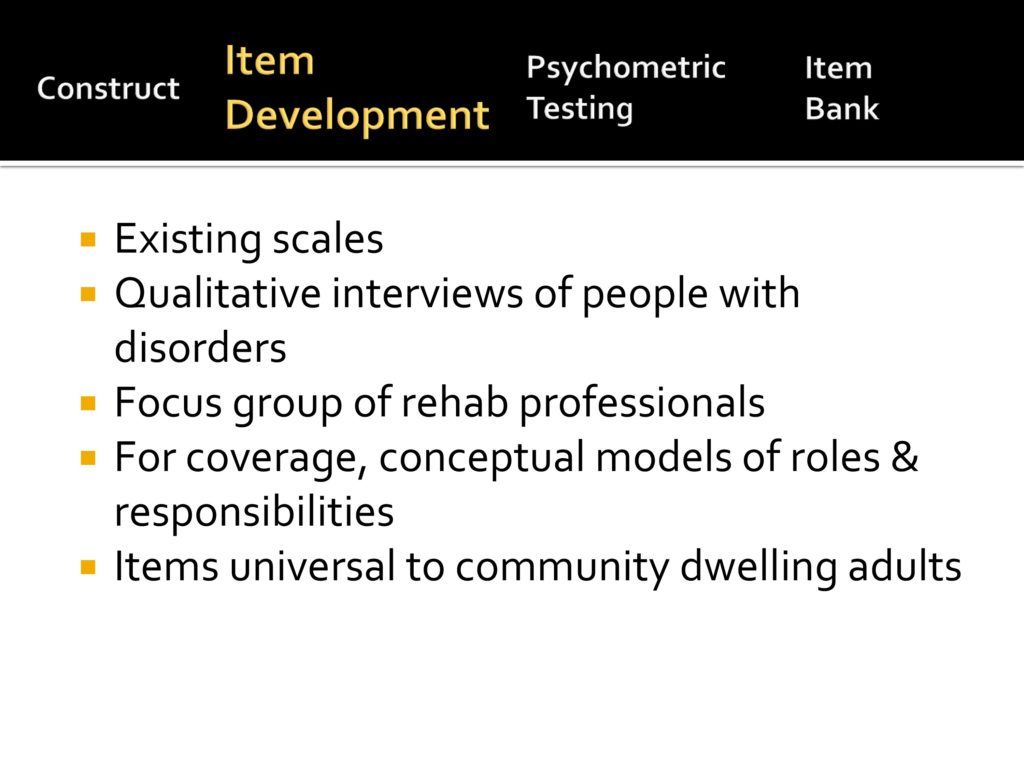

As you’ve heard before, item development has a series of things that you can do. First of all, we reviewed existing scales. Not wanting to reinvent the wheel, we did qualitative interviews with people with disorders, we did focus groups of rehab professionals. We relied on our OT colleagues especially to give us conceptual models of how people spend their time, which is fundamental to occupational therapy. And we wanted items that are universal to community dwelling adults, and I’ll tell you why we needed to do this as we continue to talk about item development.

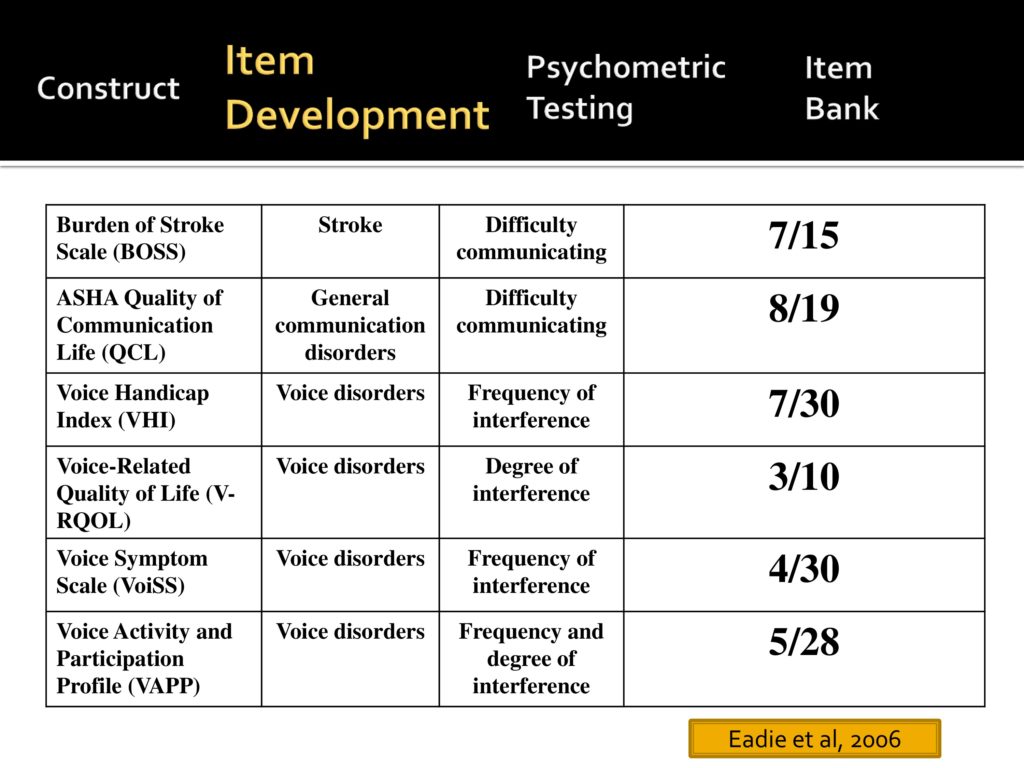

So the first thing we did is review current tests and Tanya Edie spearheaded this part of the project where we reviewed six published tests in the communication area. Some related to voice, some more general, some related to stroke, and we identified the number of items in each of those scales that we believe measure participation. What you see is that there’s no single measure that we felt was solely devoted to participation.

So we moved on and we said to ourselves, let’s develop a list of candidate items. Our first marching order from Dagmar, as we say, was to develop a set of items with a low level of not applicable.

In IRT you want to avoid items that people don’t do because they don’t fall on the scale. So we had to develop a set of items that are very typically engaged in by community dwelling adults. They represent a single factor, as we’ve talked about before, had a range of difficulty, asked about a single issue, were unambiguous, and fit the mathematical models.

And it’s interesting to hear other people who have tackled the same problem. Each group makes a set of decision based on what they, what they are faced with.

Here’s some of the decisions that we made. We said this measure will be used with community dwelling adults, not individuals in SNFs or in acute rehab settings. We wanted to cover range of life domains and a range of communication disorders, not just the aphasia, the dysarthria, the cognitive communication silos that we sometimes find ourselves in.

We wanted to focus on speech communication, although we truly believe that things like reading and writing are critical. We felt that we would have a better likelihood of being unidimensional if we focused on speech communication and we wanted to ask a single question about overall satisfaction.

Here’s some examples of the candidate items we started with; having a casual conversation with somebody you do not know well; talking with people you live with about things that need to get done around the house, so just every day communication items.

And then we went through a series of cognitive interviews, which are a very structured approach when you’re developing surveys that allow you to identify sources of response error.

So here are some of the questions:

- What does this question mean to the respondent? And it is very often that our team would think oh, anybody would know what we mean by that, and clearly they didn’t.

- How well does the responder, how well is that person able to recall the information?

- What time frame are you going to ask about?

- How does the respondent choose a response option?

And our initial interviews focused on a variety of people with adult onset speech problems and were heavily weighted in terms of spasmodic dysphonia because that was the population that Carolyn did her dissertation work with.

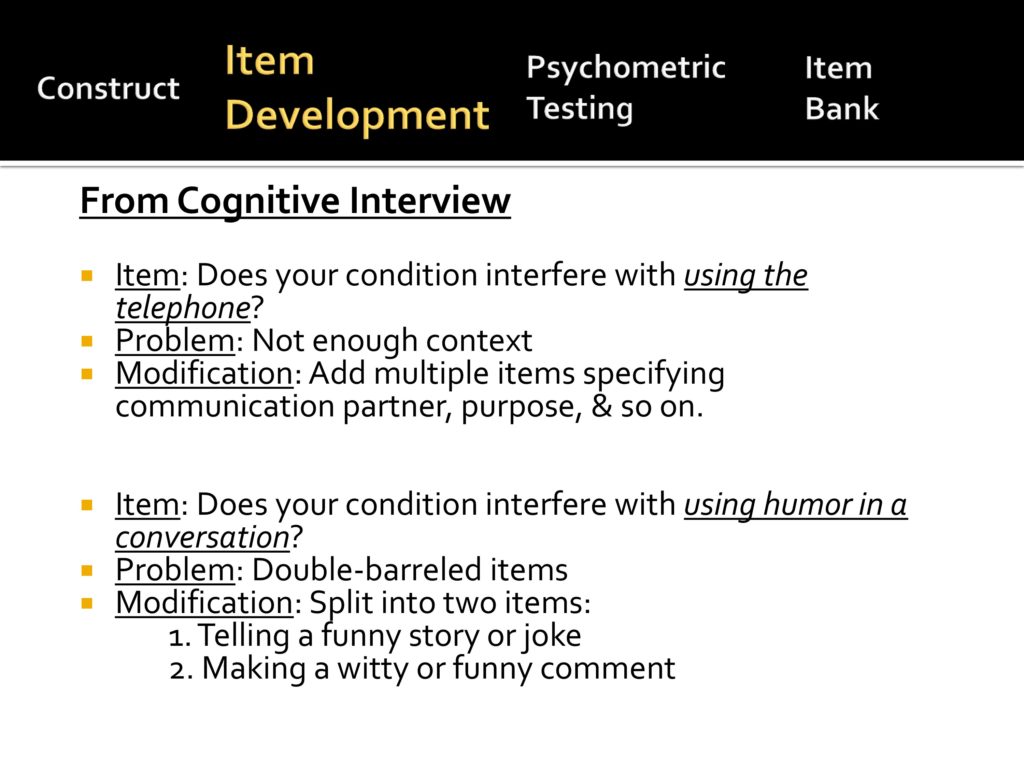

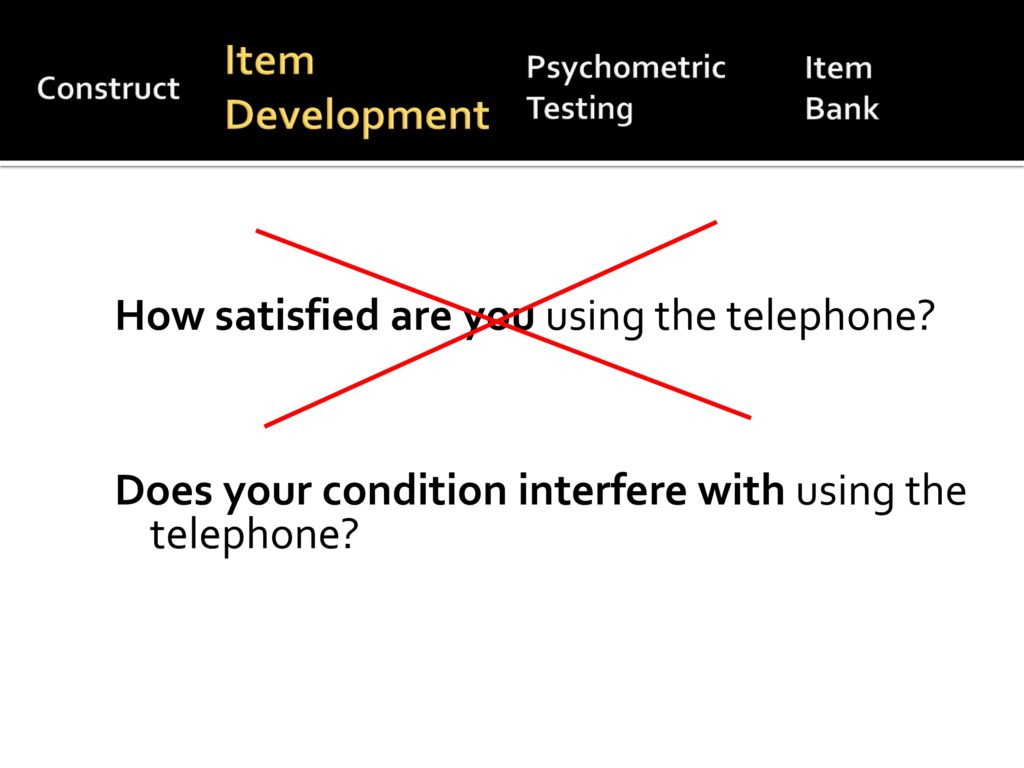

So from the cognitive interviews we learned a lot. For example, we had an initial item, “Does your condition interfere with using the telephone?” and people told us that it depends. There’s not enough context. So we modified that so that we had more information about communication partner, purpose, and so on. We made that into several questions.

Another item, “using humor in a conversation.” People said it depends. So we identified this as a double-barreled item, and we broke it into two; telling a story or a joke where you have the floor is very different from inserting a funny comment very quickly into a conversation. So we subdivided that.

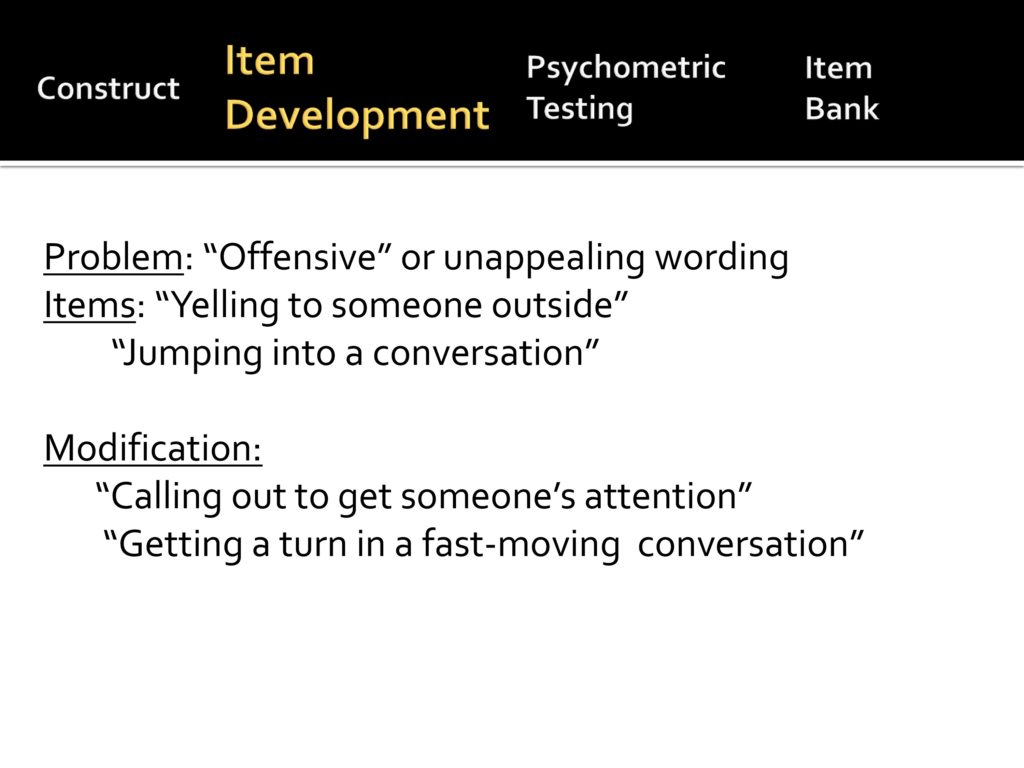

Even though we certainly didn’t want to be offensive, there’s some of our initial items that people thought were impolite. For example, when we asked people do you have problems yelling with, to somebody outside? They say I don’t yell. That’s not polite. Or jumping into a conversation. Oh I would never do that. So we changed those items slightly to say calling out to get someone’s attention, or getting a turn in a fast moving conversation. So those are kind of the subtle details of items development.

And then during your cognitive interviews you’re also trying to figure out what kind of questions you’re going to ask the respondent.

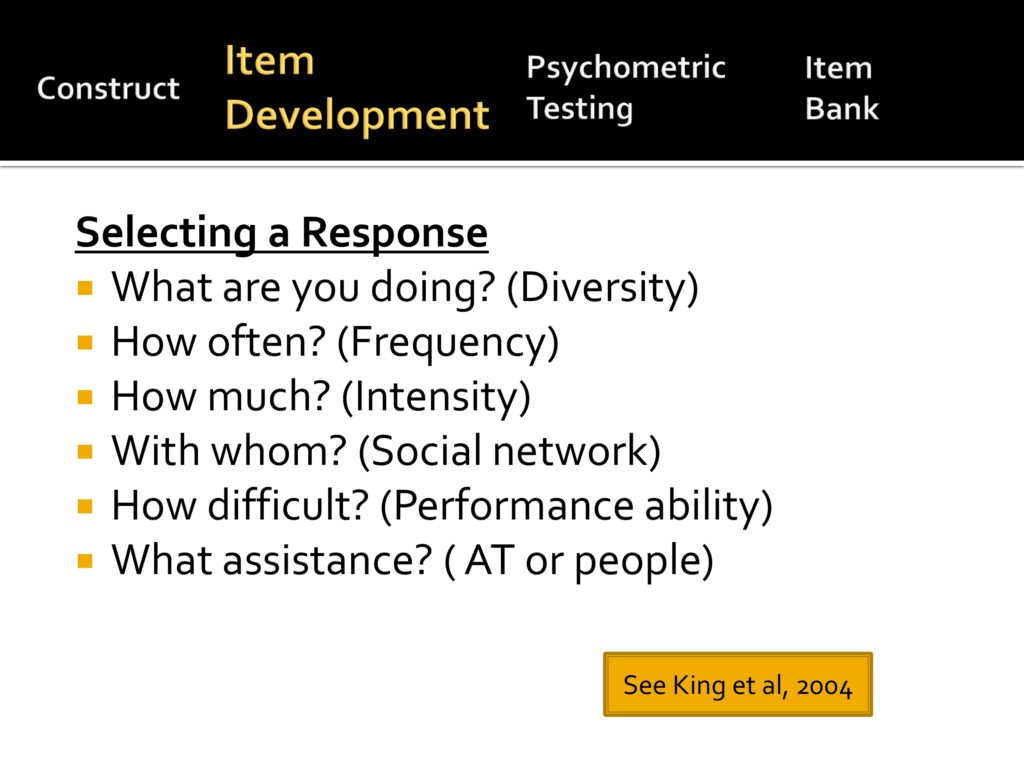

This comes from a pediatric measure of participation and they ask about each situation, six different questions, all of which are good questions. What are you doing/How diverse is your participation? How often do you do it? How much? With whom? How difficult is it? What assistance do you need?

We decided not to go in this direction because we didn’t know how to incorporate those six measures into a single measure, and by asking six questions about each item, you increase the testing burden.

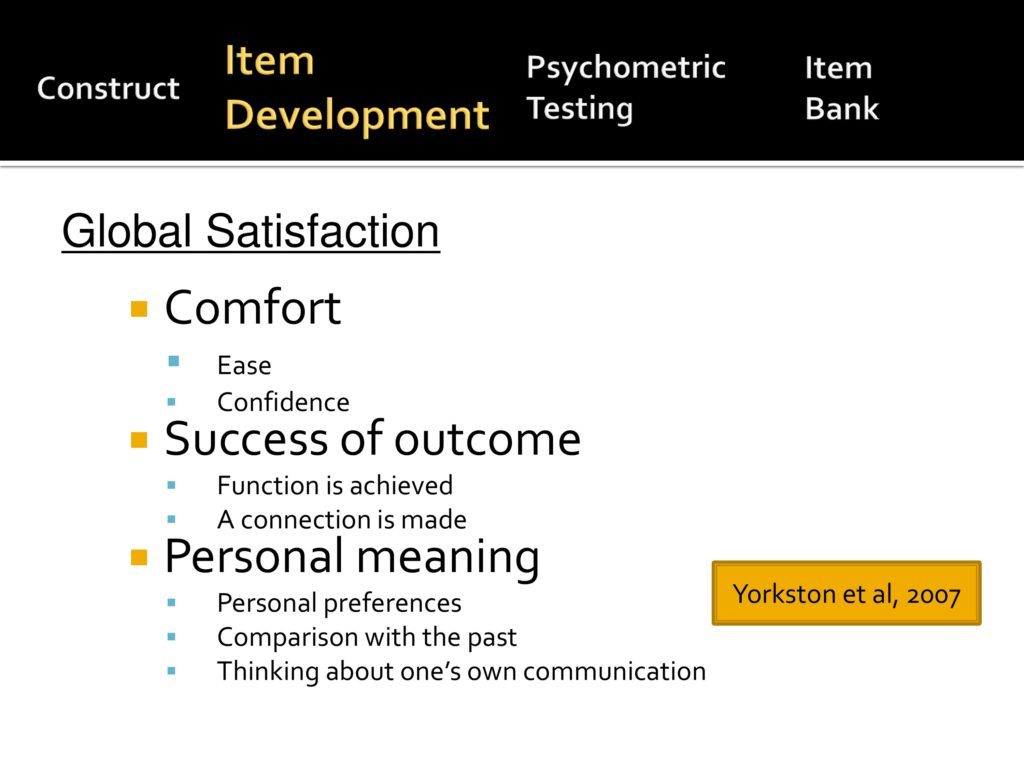

So one of our initial qualitative interviews was to say are people comfortable giving us a global indication of satisfaction? And our answer is yes.

And we asked them about the item stems; talking on the phone to get information, how satisfied are you with your taking part in that situation. And depending on what they responded, we said tell me why you rated it that way. Analyzing what they said in terms of themes, they really gave us several themes.

One is comfort. I remember one of the first women that we interviewed said, “Oh, satisfaction. You mean you’re asking me how comfortable I am.” And she was right. We were asking her how comfortable and comfort means how easy it is and how confident you are.

Other people talked about success of the outcome. I got my message across. Again, communication is special where it’s not only getting your message across, but making a social connection that was important.

Then personal meaning. I want to do this activity, this is important to me, or not important to me.

Then we took the items with our stem and did more cognitive interviews, and we very quickly learned that people were not interested in the word satisfaction and they very clearly told us I’m not satisfied that I have spasmodic dysphonia, don’t ask me how satisfied I am, ask me what problems it caused me.

So, much to our dismay we made it a negative. Does your condition interfere with using the telephone?

You notice that we use the word condition rather than speech because one of our people with a lot of insight, we call him “The Soup Man” because he told us when we said, asked him should we talk about your speech or should we talk about your MS? And he said don’t ask me about my speech because my MS is like a pot of soup. It boils away, and the speech may be the carrots that I’ve added to the soup. I can tell you when I added the carrots, but once they’ve stirred around a while I can’t tell you whether it’s my speech, the fatigue, my vision problem, the soup gets integrated. Therefore we are asking about a generic condition rather than speech.

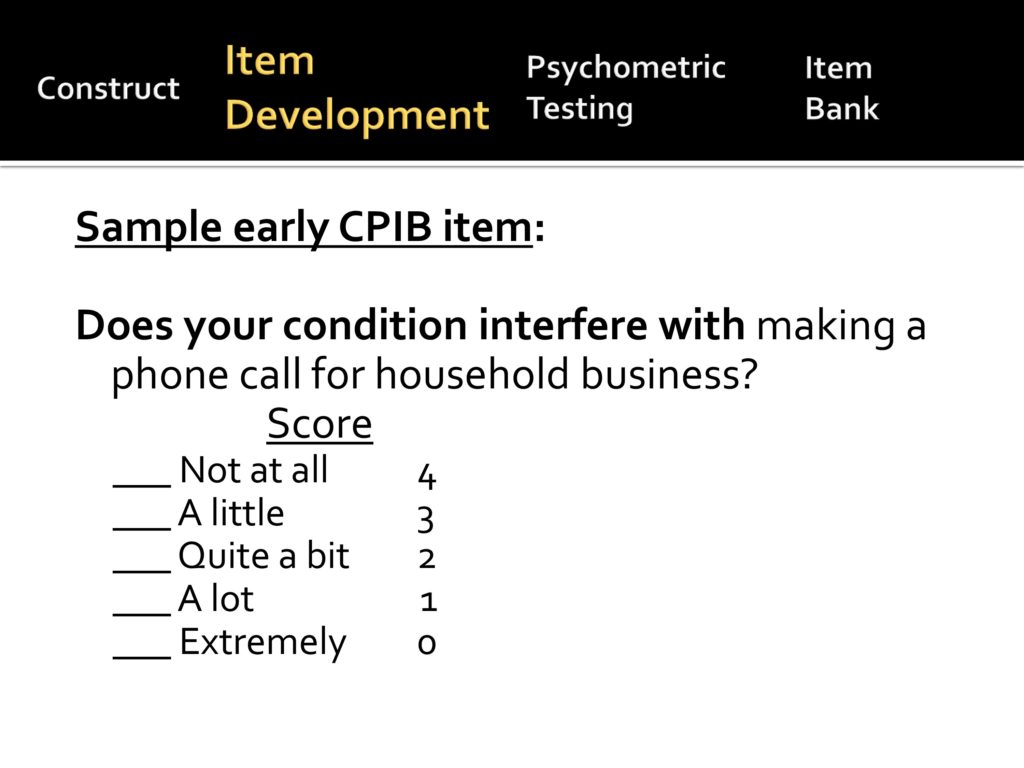

And here’s our early samples. Does your condition interfere with making phone calls for household business and we started with a five-point scale.

Psychometric Analysis

Back to our over overview, we talked about the construct, we talked about item writing, and here’s where I ask myself why am I standing here when Carolyn Baylor and Will Hula much more capable talking about psychometric analysis. My only relief is that Karon Cook isn’t standing in the front row.

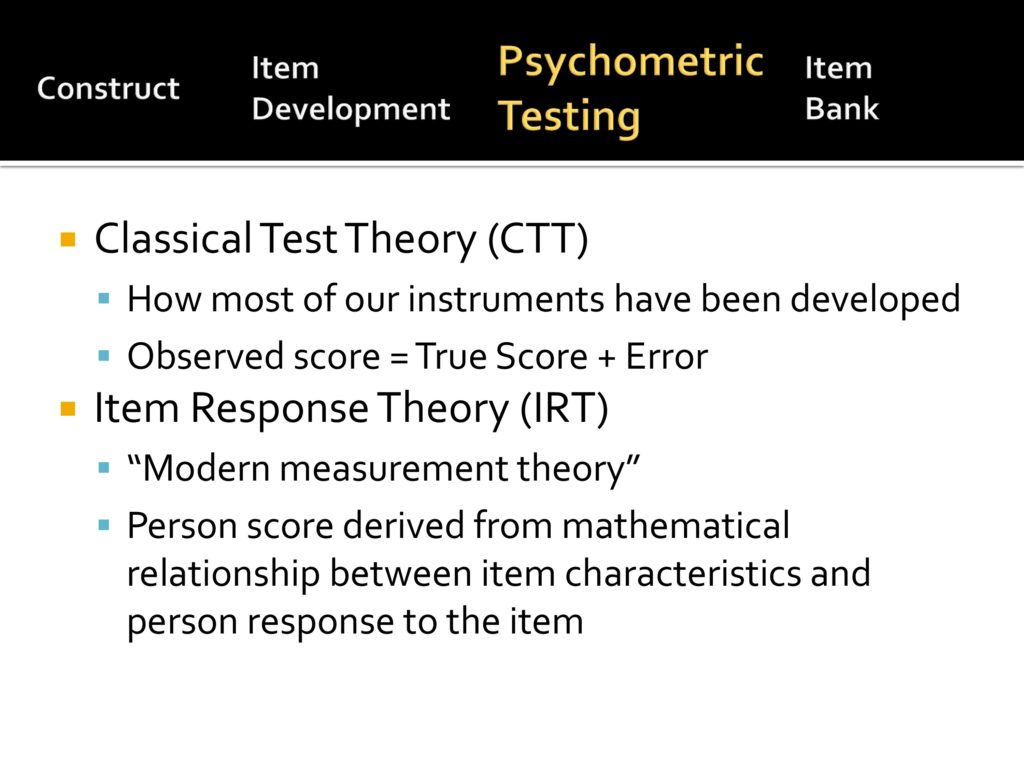

But here’s my attempt at talking about the psychometrics of this, and as Karon said, this is different from classical tests theory where you give the whole test and your observed score is really the sum of the true score, but plus errors, and you always give the whole test and you compare it maybe as a percentile rank to some known population.

Item response theory, also known as modern measurement theory, a person’s score is derived from a mathematical relationship between the item characteristics that you know a whole lot about and a person’s response to those items.

So advantages of item response theory, it measures something that you can’t measure directly, a latent trait. You know a lot about the characteristics of the item and the way people respond to it and it estimates a person’s level of the trait being measured.

Advantages are that it approximates an equal interval scale, it allows for mathematical operations; adding and subtracting, and averaging. It provides a common metric for equating across instruments if they’ve been developed with IRT, and it removes dependence on specific items and allows you to shorten testing.

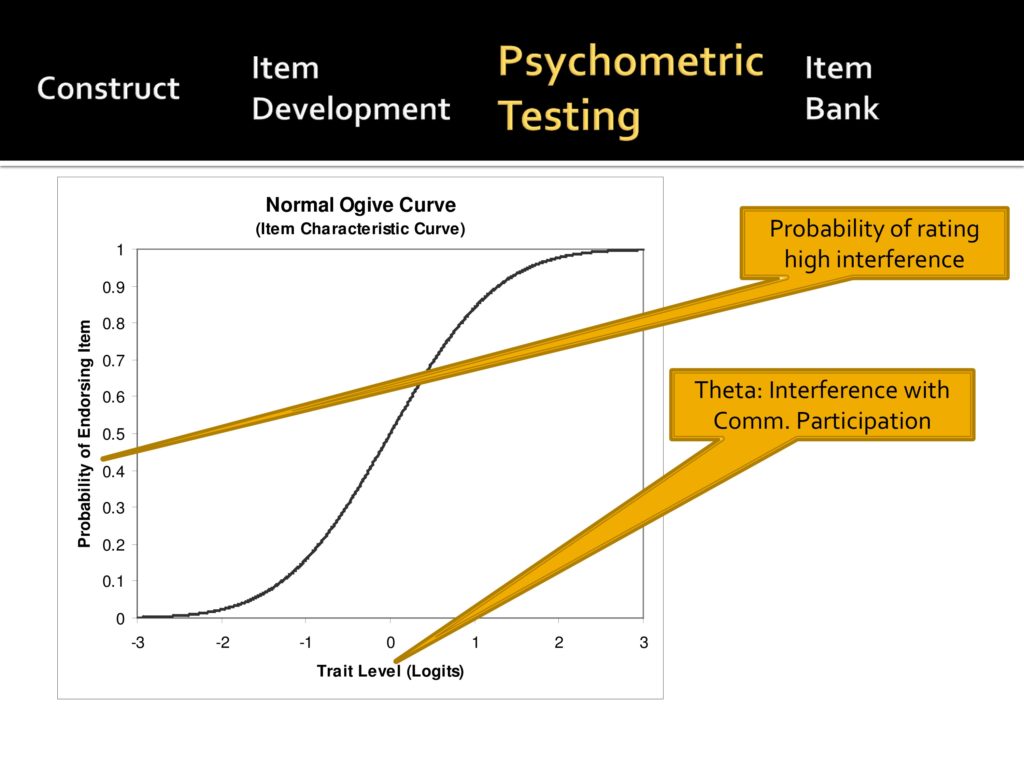

Karon didn’t dive this far and that’s why I’m a little uncomfortable with me diving this far. This is the Ogive curve where you have a trait level that’s measured in units called logits and the trait level is called theta. With our scale it’s interference with communicative participation and then along the vertical axis you have probability of rated high interference.

If you can see the minus three, that means a very low interference. A person who does not have a lot of problems, very unlikely to endorse an item. A plus three on the other hand, is very high interference, almost 100% likely to endorse that item. And there’s an S curve that goes between the two.

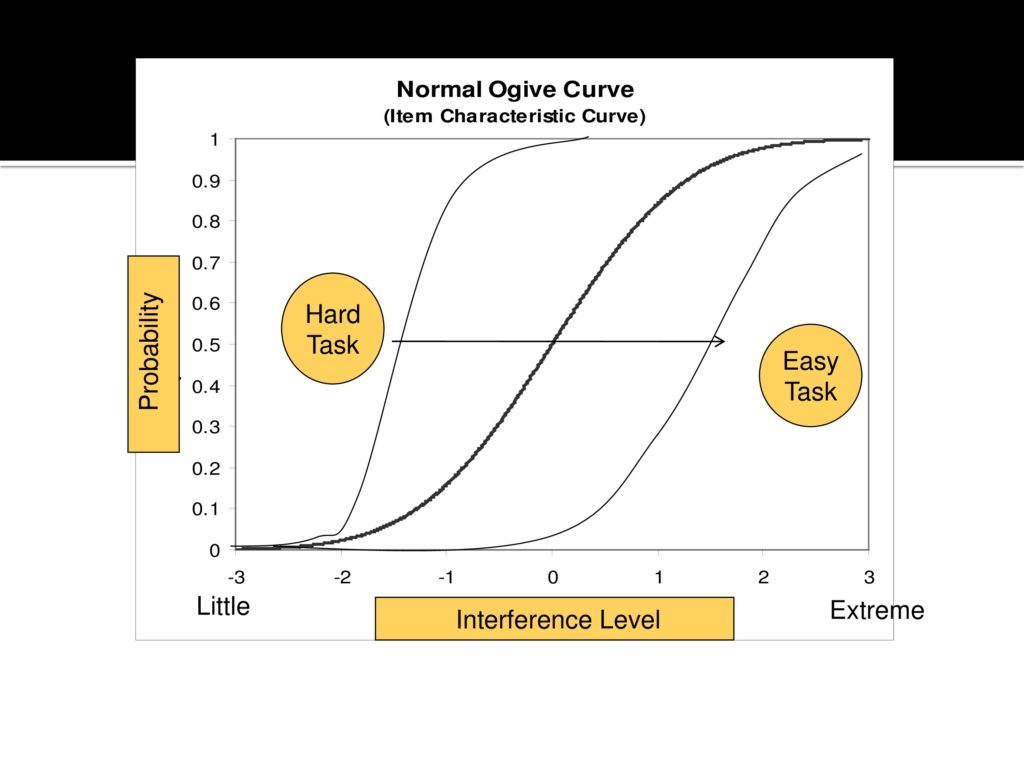

So when you develop a test, each item has an Ogive curve whereas a harder item, even people with just a little bit of interference will start having difficulty and reporting interference. With an easy item, only people with extreme interference will have problems.

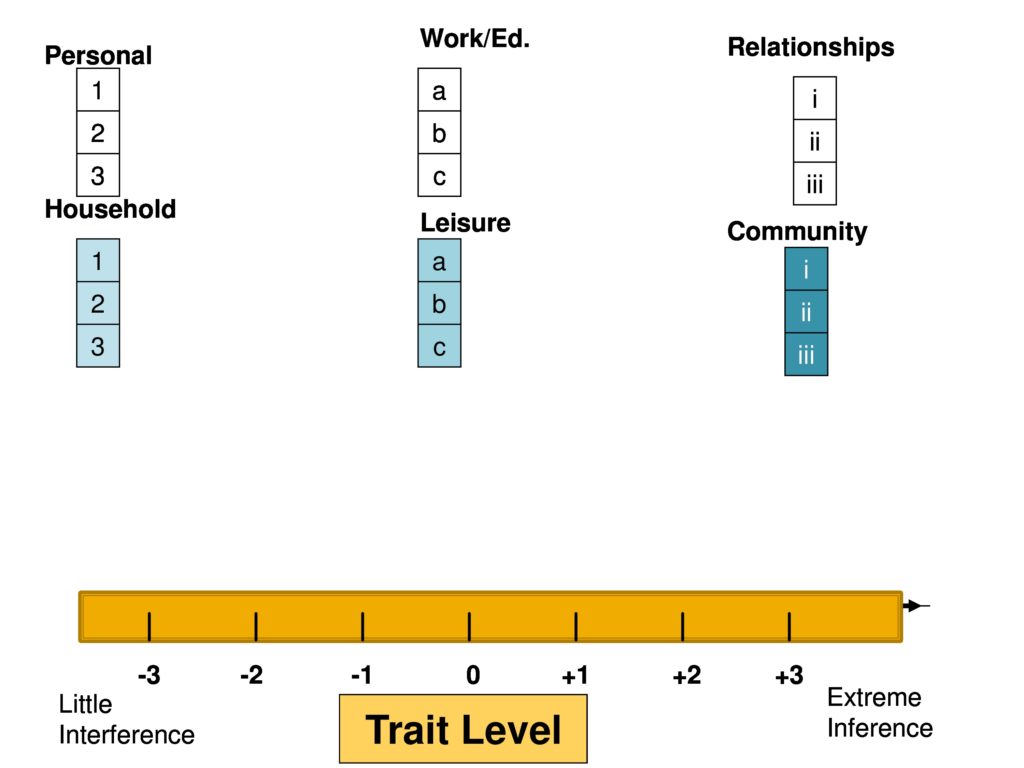

So what you’re doing when you’re creating your item bank is to have many, many of these. We have items from these domains that we, from an armchair, thought were important, we give the items to hundreds of people and then that places them along the trait level and in this case it’s just fine to have multiple items at a single trait level, as you see here. It’s not so good to have no items, for example at plus two.

So if we were developing this test, we would go back and try to create some items to fill in the gap.

So our original response categories were five.

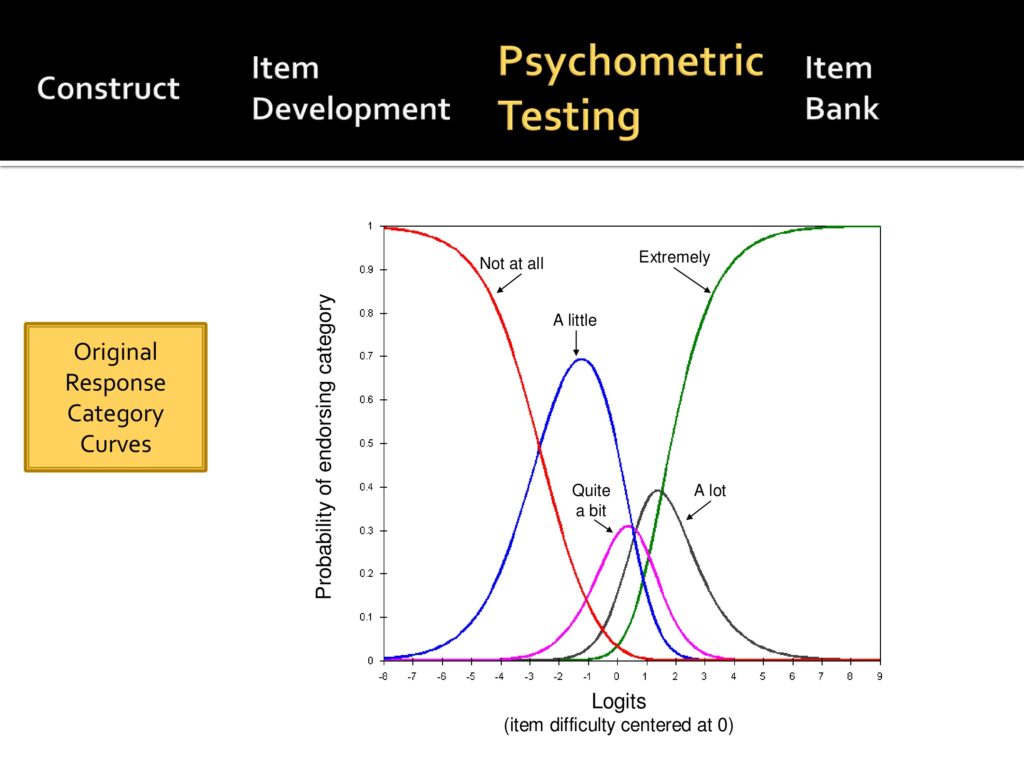

When we actually did the data on a large group of people, you see that there are two curves there that are kind of buried, quite a bit and a lot. This told us that those categories really should be merged.

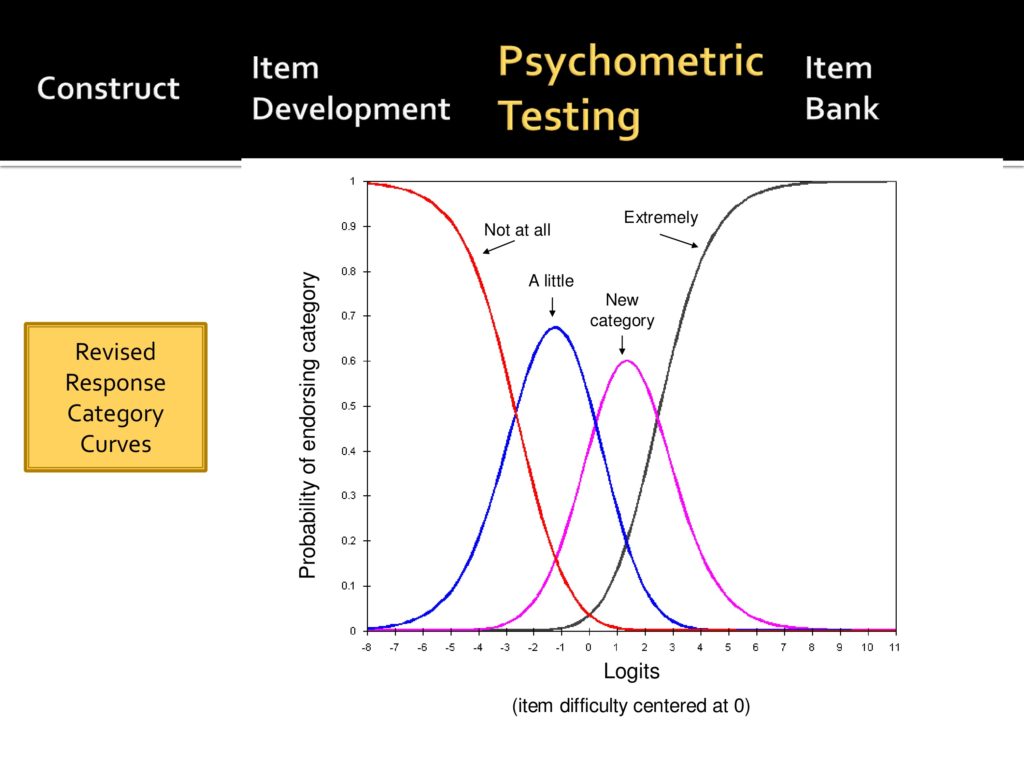

And when they were merged it looks, you see a distinctive peak with each measure.

And that resulted in an item that now only has four levels: not at all, a little, quite a bit, and very much. It reduces the burden of test taking on the person and makes it easier all the way around.

So now we have data from a large sample of people and then we begin to say does this data, this item bank, or list of candidate items abide by IRT assumptions. As we’ve heard before, they include essential or sufficient unit dimensionality, model fit, and local independence.

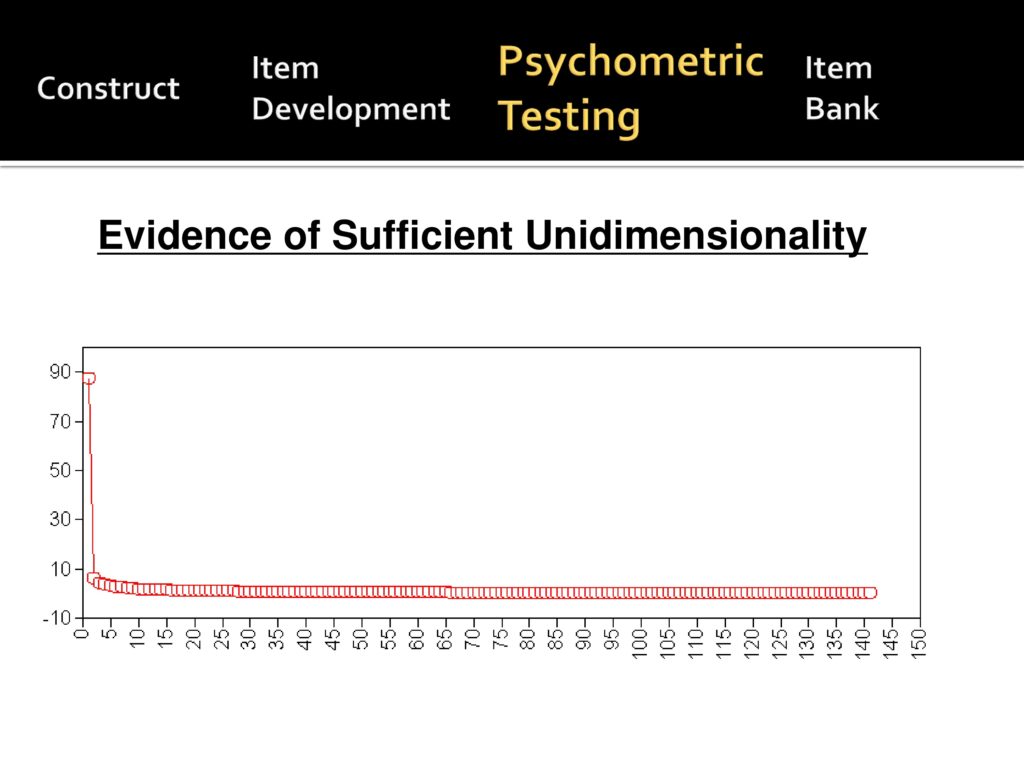

Here’s the data from our initial. We started with a little over 140 items to show that, to suggest that we have good enough unit dimensionality. We essentially have a single item and all the others are much, much less.

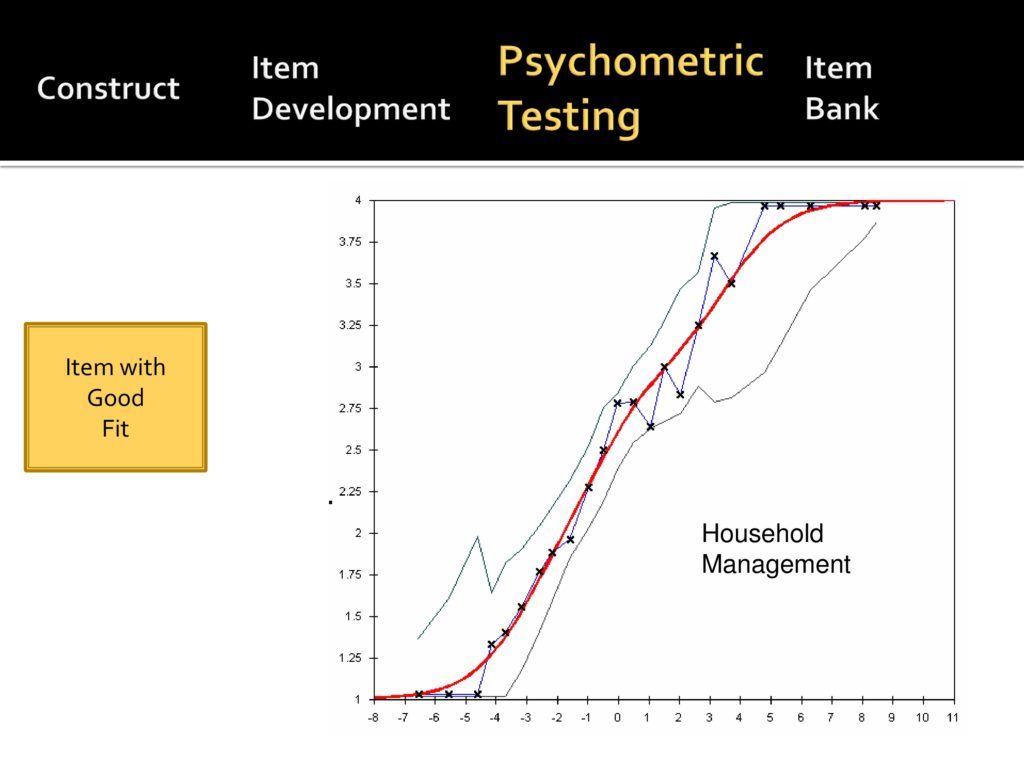

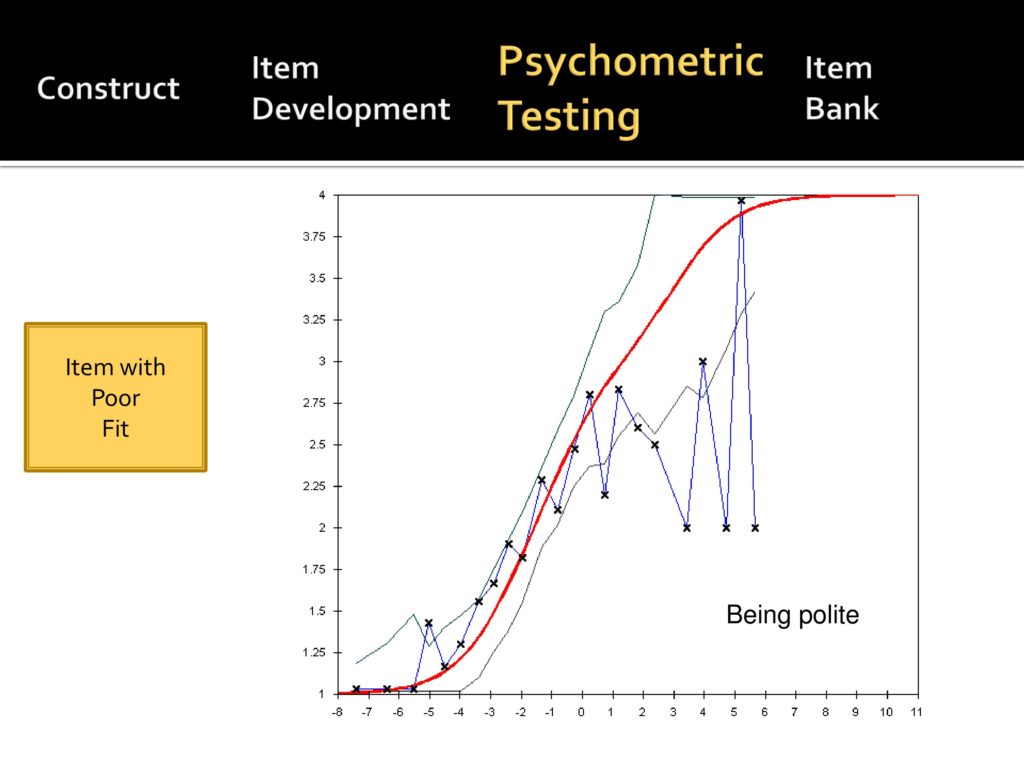

This is data about goodness of fit. The red line is the mathematical model and this is an item about household management and communication and the squiggly blue line is our actual data.

This item passes the goodness of fit model, and it continues to be included.

This is an item that we liked, but didn’t work out psychometrically. It’s an item about being polite. It worked out okay for people who have little interference, but really fell apart and became jagged for the people with a more extreme interference and this was out of the item bank because of that.

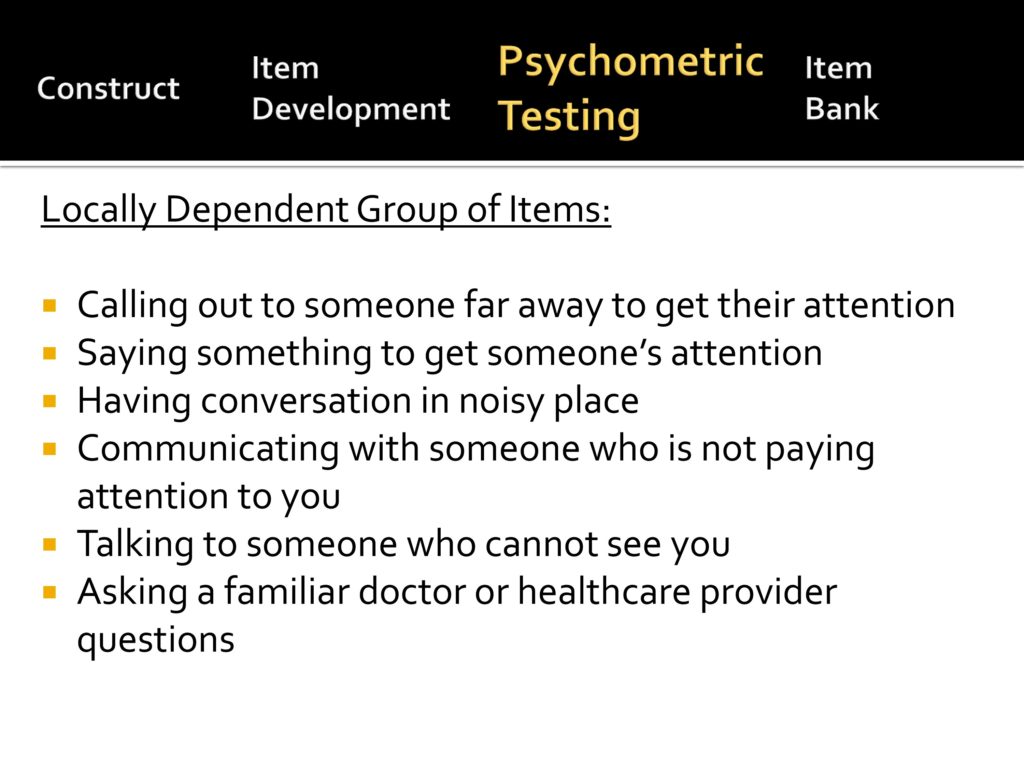

Local dependence is basically the concept of are the items correlated with one another so much that they don’t give you the new information. You can’t assess item dependence from an armchair.

These are the list of items in our initial scale that were not independent and some of them kind of hang together as you read them and others you don’t know why they correlate.

But as we say Dagmar told us we could only, we had to throw out items that had a high level of dependency. So we did.

Item Bank

Back to our model, we talked about the construct, we talked about the item development, psychometric analysis, and now I’ll talk about the item bank itself.

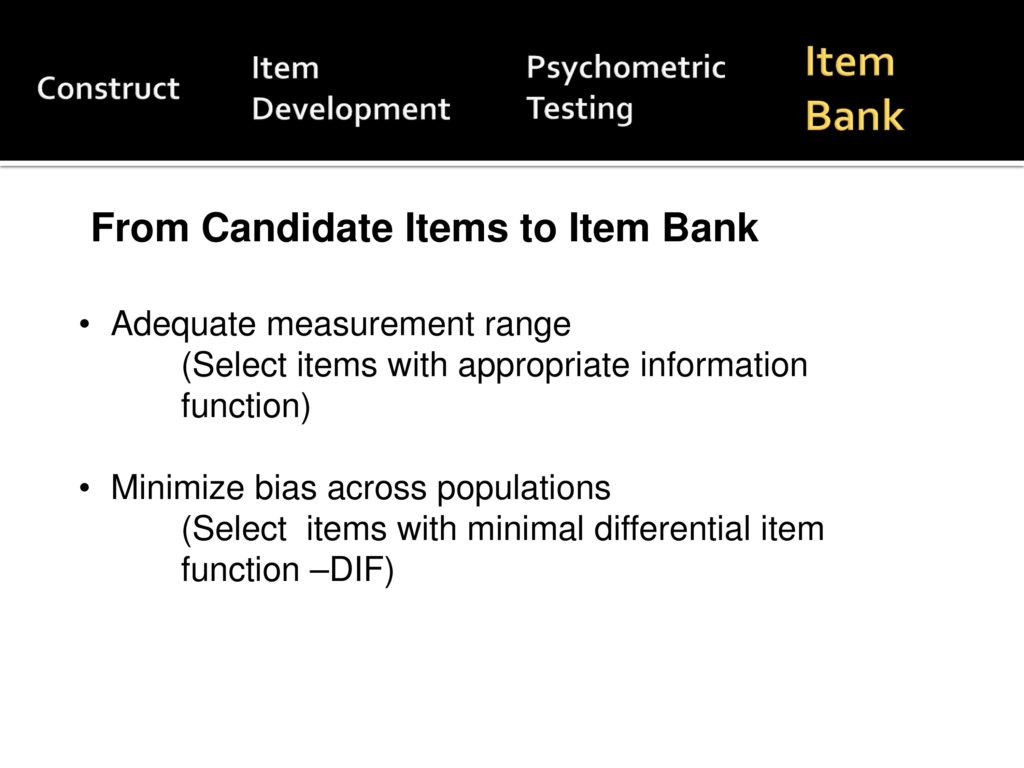

Now we have a set of items that mathematically perform adequately. We want to select a set of items that adequately measure across a broad range and minimize bias across populations.

We want items for whom people with Parkinson’s disease respond in a similar way to those with head and neck cancer to those with spasmodic dysphonia.

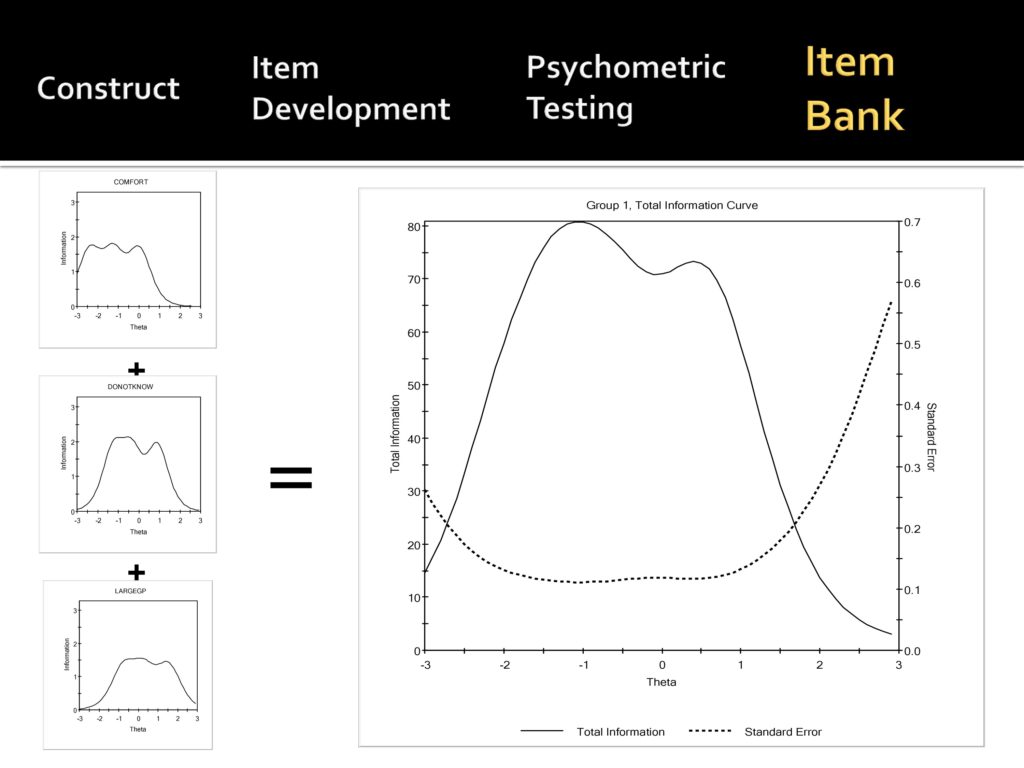

So what we have here when you’re constructing the final item bank, you look at what’s called information curves. Again, we want the solid line there in the larger graph is the information curve, the higher the better and the broader the curve, the better. So this suggests that from minus, what, minus 2.8 to maybe plus 2, it’s pretty good. The dotted line is the measurement error, and you want that to be low. So you see their inverse relationship.

So you select items that give you broad representation and have the highest information curve.

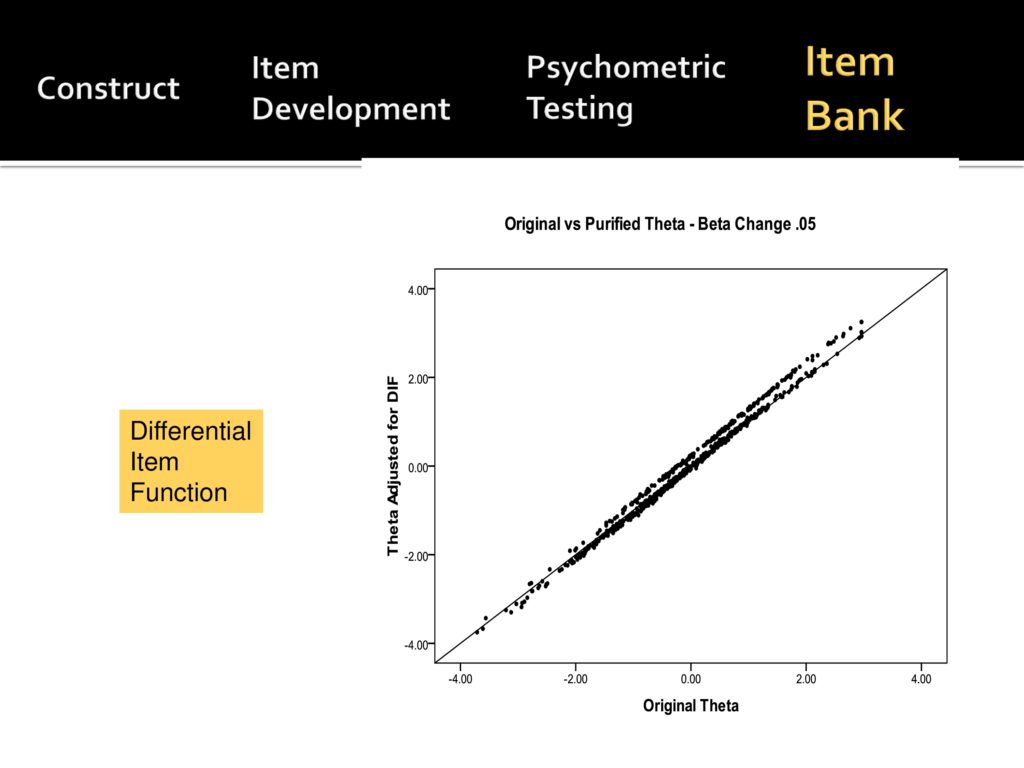

This is from our data related to DIF analysis and we’re asking the question about bias across populations. So you say what’s the original theta and what’s the theta when you adjust for DIF and fortunately for us, this graph shows that they’re pretty well correlated somewhere over .98, .99.

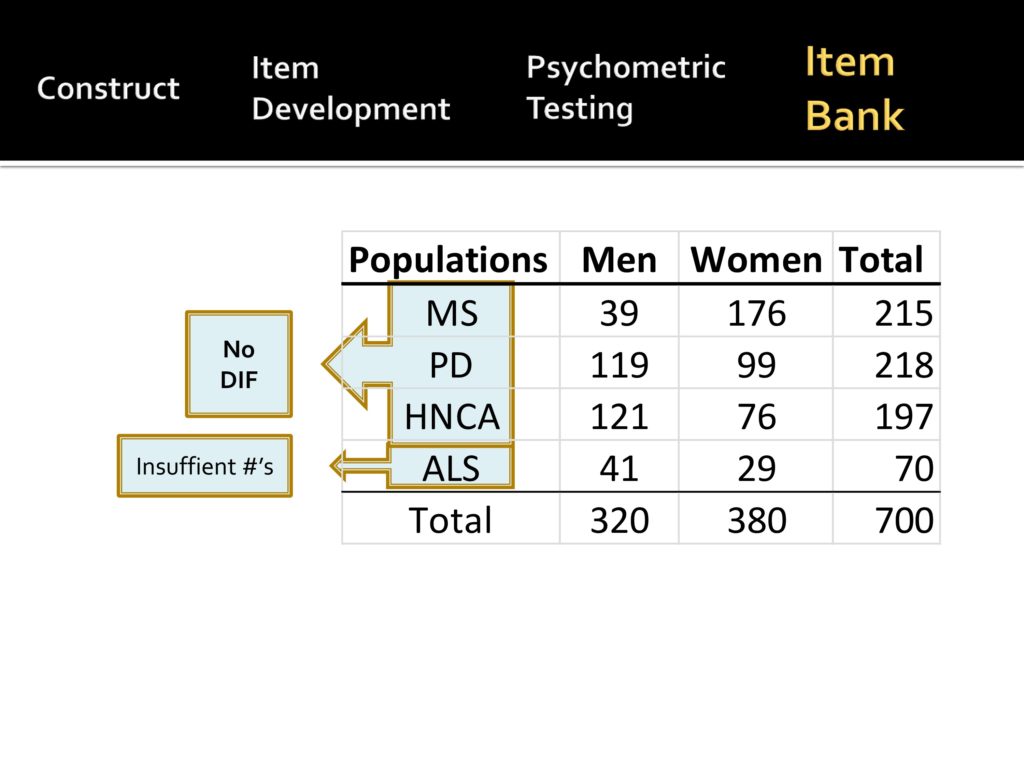

In our recent R03, looking at that data we have populations, we have people with MS, 215 people with Parkinson’s, over 200 people with head and neck cancer, and people with ALS.

What we found is there’s no DIF between MS, Parkinson’s, head and neck cancer, and you need at least, around 200 to do the DIF analysis, and we didn’t have enough people with ALS to suggest whether or not there’s DIF.

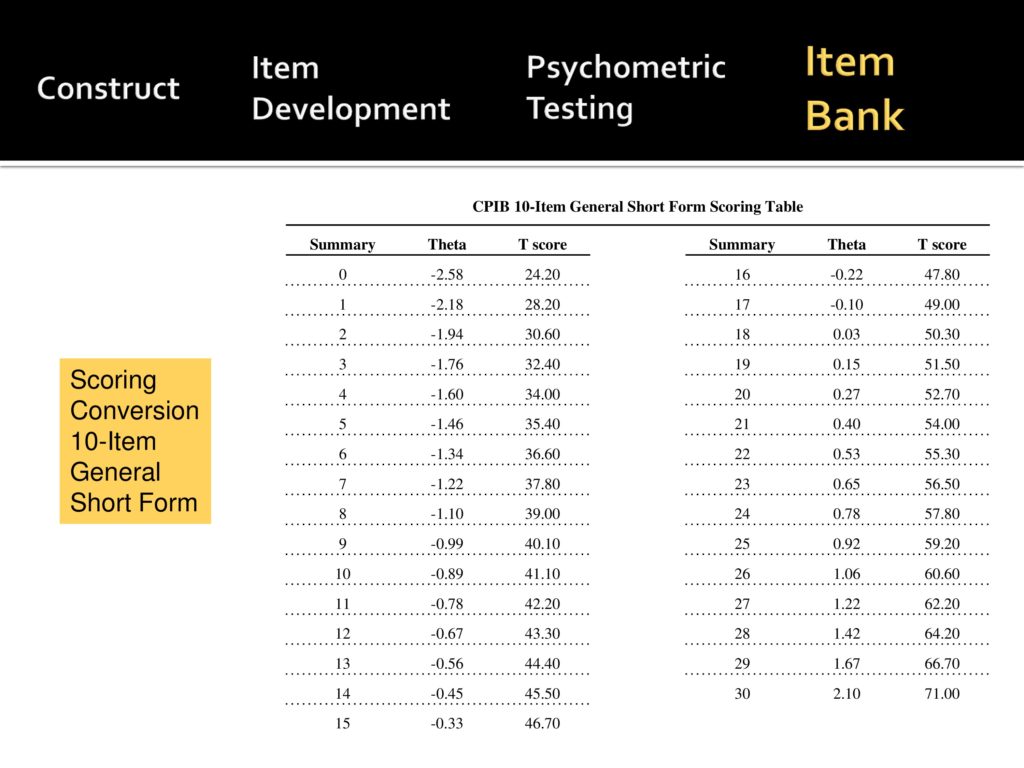

So to bring you to the current date, we’re now able to develop a 10 item general form that covers the range of difficulty or levels of interference, and it is in the JSLHR publication pipeline so that you’ll have the items and a scoring template for that.

Future Directions

Future directions, we have many. The first as previous speakers have said, we really want CAT scoring, so that we can go to the assessment center and have people score.

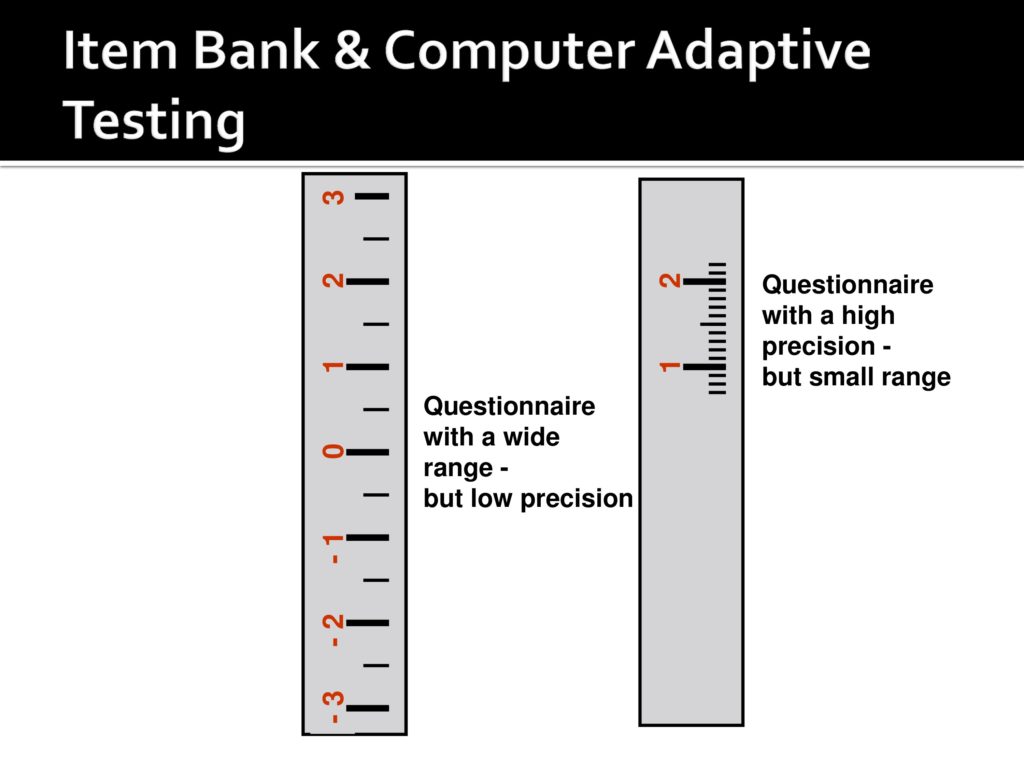

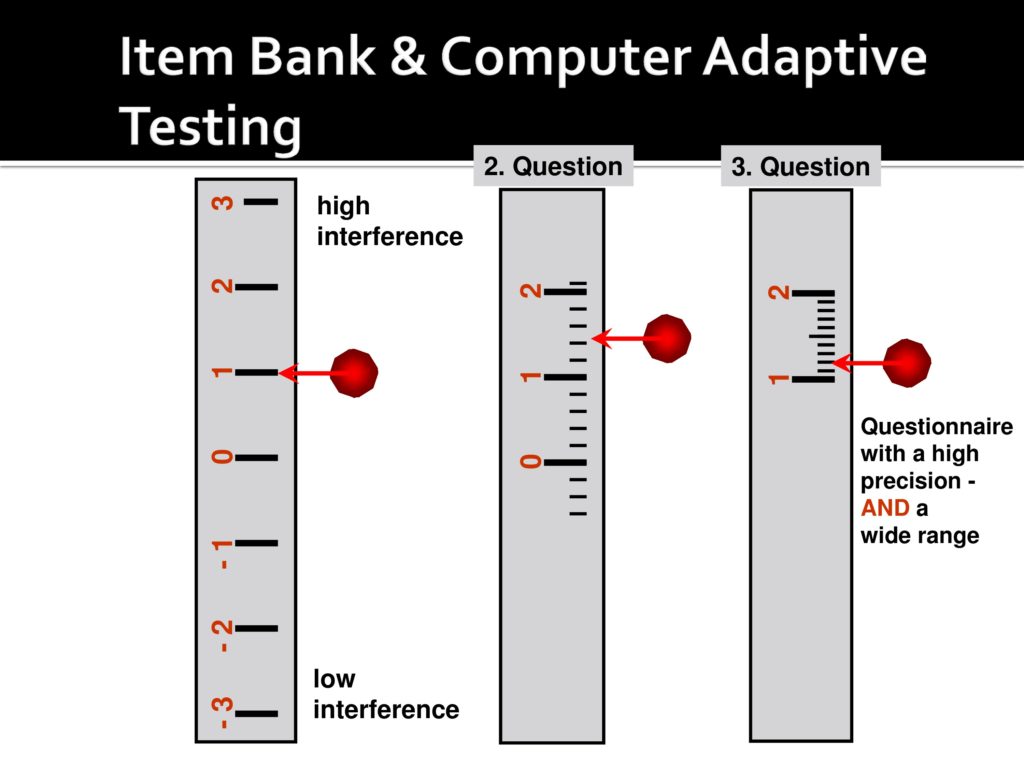

To recap a little, you want a test that gives you both a wide range and high levels of precision.

What CAT does is start in the middle.

And then depending on the response to the first one narrows and narrows your ticks on your yardstick with each question until you come up with a precise measure.

And allows you to assess a broad range of communicative participation. So that’s something that we are intending to do.

We’re also beginning to look at what things are associated with communicative participation.

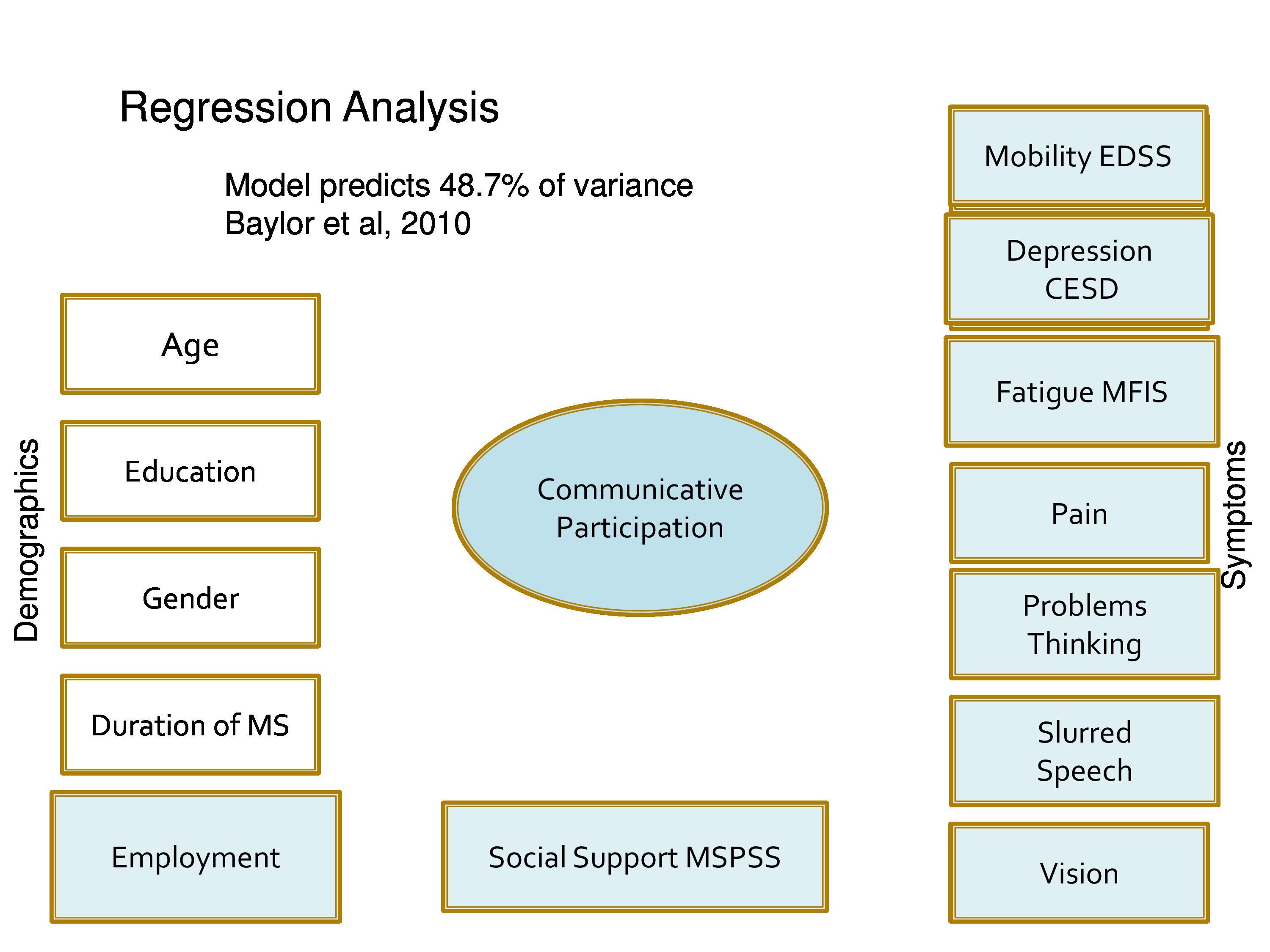

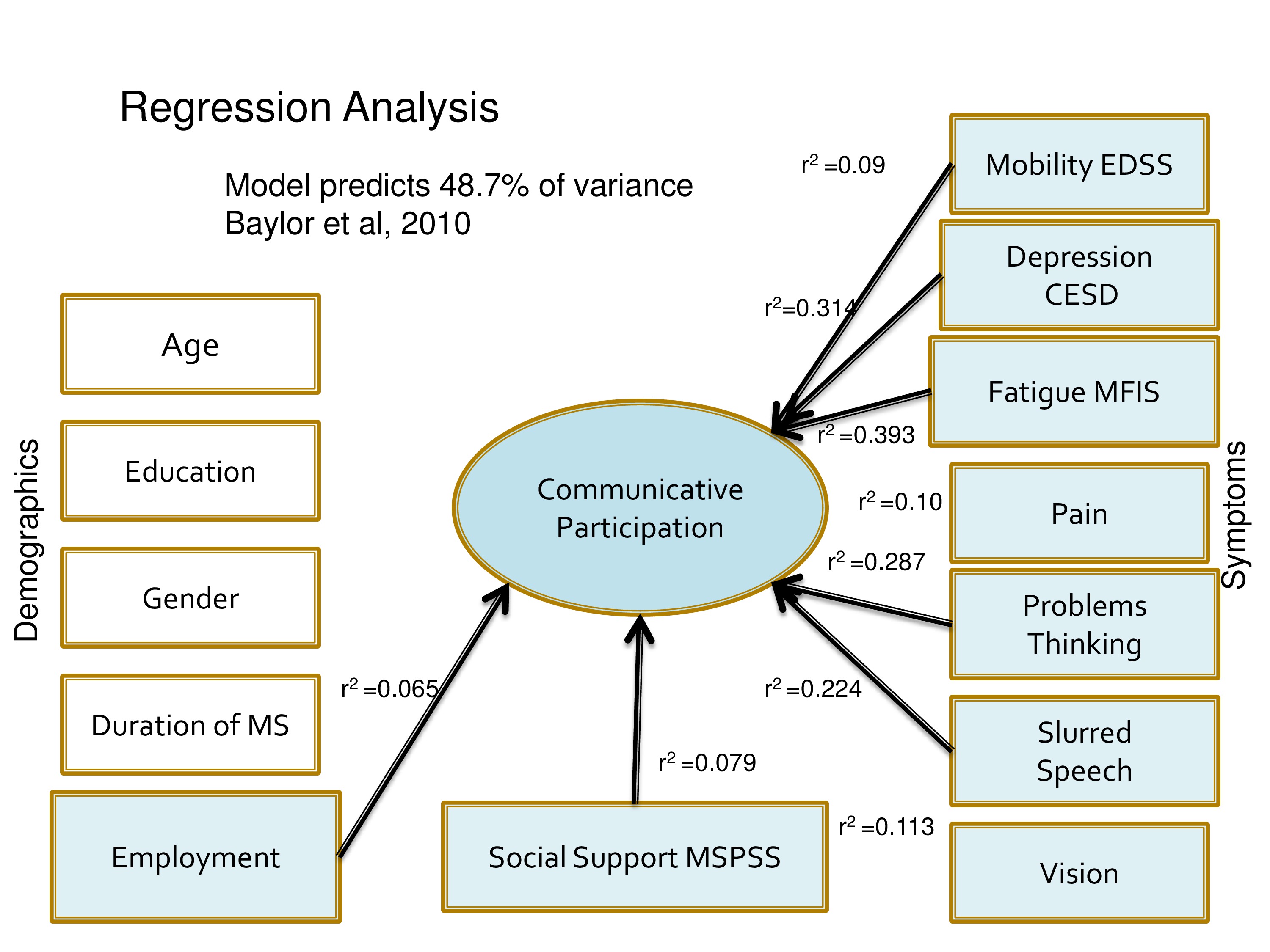

We started with a preliminary of the measure that we gave to about 500 people with multiple sclerosis and this is what we threw into the regression analysis: age, education, gender, duration of MS, employment, status of social support, mobility, depression, fatigue, pain, problems thinking, slurred speech, and vision.

Our results suggests that fatigue was among the highest associated, depression, problems thinking, slurred speech finally comes in, vision, pain, social support, employment.

This model predicts a little less than 50% and here are the numbers. Good and bad news, we obviously are wondering what’s the other 52%.

On the positive side it also suggests that it, in terms of enhancing communicative participation, we have many things we might do. OTs can help us manage fatigue, psychologists can help us manage depression.

We certainly can work on speech, social support is something that our team can work on that we don’t need to depend on making speech perfect to potentially influence communicative participation. So we want to look at associations with other populations.

We want more populations and Carolyn was very fortunate to receive funding from the ASHA Foundation to add aphasia to our list to see what support people with aphasia need to do our task and how much aphasia is too much and what sorts of people with aphasia can take the test.

We’re looking at cultural and language translations, not a trivial matter.

We’re looking very importantly at issues like is our measure sensitive to change? If somebody goes through LSVT, will their participation measure change?

And equally important is how much does it need to change to be a meaningful change? And we really are very interested in pursuing that avenue.

So I’ll just close with a slide of what we’ve learned. The first is there’s no better way to highlight your limited understanding of something then to try to measure it. This has been a 10-year exercise in learning what we don’t know.

That a team is necessary that people with communication problems need to be integrated at every step of the way. We need qualitative researchers, we need quantitative researchers.

And we’re not finished yet.

Questions and Discussion

Question: I was thinking about how a speech-language pathologist might be able to use this scale to track interventions to increase participant or client participation. You mentioned this as a future research need, but I was just wondering from your perception, having used this scale, do you think that the scale would be sensitive to small changes?

Kathryn Yorkston:

Let me try to answer your question, but not from the perspective of the scale, but from perspective of what people tell us in our qualitative interviews.

We’ve interviewed people with Parkinson’s disease who have been through the LSVT and just as a side light we always ask them would your scores have changed because of the treatment, and the people that we’ve asked say absolutely.

We don’t have any data and that’s why it’s listed in the future direction. We would love to see how much it changes, and whether the change is persistent.

You know this has been kind of a mixed method of research program where we at every stage do qualitative work, and not only look at the scores that change, but also talk to people and say is that meaningful to you? You said now you can do this and this, does that make a difference? And that hopefully be our future direction of working on this scale.

Question: In one of your slides for the goodness of fit, you had illustrated politeness as particularly difficult to measure. Did you find some constructs more difficult to fit than others? I’m kind of curious about politeness – because I work with TBI, and also because it’s also kind of socially sort of slippery.

Kathryn Yorkston:

Well we’ve really struggled. We like the concept of politeness just as you said, because it’s important in some populations. We reworded it many times and never got it to work. So we had to finally get rid of it.

Carolyn Baylor:

Off the top of my head I can’t remember others that didn’t fit, other than the not applicable. Originally we had really tried to go very broad with a lot of topics. We had items about talking to your pet and items about participating in religious services and a lot of things like that just did not apply to enough people that we had to throw them out and that sort of thing.

Kathryn Yorkston:

Just to expand on that, if a person doesn’t do it, where do you put them on the scale? Are they low interference, no. Are they high interference, they just don’t fall on the scale. That’s why Dagmar very rightfully would not let us put anything on with more than just a small percentage of people that said I don’t, that say I don’t do this. So that was more major than other areas.

Question: You said that one of the things that emerged from your qualitative work was this notion that some of the items needed to have more context attached to them. You gave the example of a phone call, and you developed sort of several items with different kinds of contexts around that. Did you find in then in the subsequent psychometric analyses that doing that caused local dependence, caused these subsets to be correlated with each other over and above the trait?

Carolyn Baylor:

You’re absolutely right. Phone is just one example of several of these we ran into, but using phone as the example. We started out with just a couple general phone questions and the qualitative feedback was, “I can’t answer that because it depends. I’d answer this differently depending on the situation.” So I think we ended up with writing eight, seven, eight, nine phone items that we tested in the IRT, and then as you mentioned, we come up with a lot of local dependence where quantitatively they’re overlapping a lot.

So then we ran into what Dagmar and I would always go back and forth about — I would want to say qualitatively, we want to keep those items because our participants are telling us they get at different situations that are meaningful to them. And Dagmar would come back and say, but quantitatively if they’re dependent, you don’t want that redundancy. And if you’ve got one or two phone items that are doing well statistically, you’ve covered it. So sometimes there was kind of that tension between what we wanted clinically, and what she said is good for measurement and she almost always won.

Question: If we’re doing computer adaptive testing, it would seem relatively simple to ask a few preliminary questions of the person such as are you trying to return to work, are you trying to return to school, and through those questions have some of the items get sorted. It seems to me that would allow you to get the most important questions for certain subtypes of populations.

Carolyn Baylor:

You know, I think you could conceptually do that, as long as the items still fell along the same trait and the same scale because when you use the CAT, every item in the item bank has to fall along the same continuum of one dimension along the same difficulty. So otherwise I think you could have some of those as kind of the sorting items to get people started if it met that underlying criteria.

Kathryn Yorkston:

I’ll also add that Dagmar says if we go to other populations, like people who use augmentative communication systems, we may be able to use a set of core items, but it’s perfectly permissible in a population, a different population to have a supplemental set of items that relate to that population. Obviously tested and whatnot.

Question: I’m thinking about some of the populations that you could use this on and how they might vary in terms of denial or even awareness, and I’m wondering if you have thought about you know running this scale on their caregivers, their loved ones, and to see if you have accuracy or reliability or correlation between the two.

Kathryn Yorkston:

Yeah, that certainly is a question that we can answer empirically, and it should be done. It may be that certain population’s proxies are very good. I think Neila may be able to respond to that in terms of some people have done items with people with ALS and their partners and they just are very close to each other. On the other hand people with Parkinson’s and their caregivers not so much. So it may depend on populations, but that is something that we should look into.

Neila Donavon, Lousiana State University:

I’m working on a much smaller less-elaborate, less-well developed tool than hers, but still plugging away at it, eight years I guess. And we did find that people with PD and their proxies, there was a significant difference, but it was very small.

The argument then goes to this idea of with, you know we always thought people Parkinson’s have this deficient of insight, but maybe it’s really not there as much as we think it is.

On another instrument that I’ve worked on for functional cognition for traumatic brain injury, yet to be published, but we found that proxies and the people with traumatic brain injury on observable functional cognitive items weren’t that far apart in their measurement. But we only had people that were in outpatient rehab and at least one year post. So we didn’t really have anything that would measure insight earlier.

Question: I was just wondering if you have done any convergent volatility or concurrent volatility with any other measures. If you’re doing that or plan to do that, what measures would you choose?

Carolyn Baylor:

Yes we have done a little bit of that. It’s all been self-report data thus far just for feasibility purposes. So unfortunately we don’t have anything where we compare like a clinician major of disorder severity with participation or those sorts of things. But a smattering of data we’ve analyzed so far for a couple of our voice populations like spasmodic dysphonia and laryngectomy, some work with laryngectomy done by Tanya Edie. Correlation with the voice handicap index, which is a very common voice quality of life measure. The correlations have been about .6, .7. And we’re really comfortable with that because we expect some overlap with the VHI because the VHI touches on some participation issues, but also covers other issues as well.

We’ve tested it against some more general health related quality of life, like the PROMIS global health, the PDQ8, which is a Parkinson’s, another health head neck cancer quality of life, you know for the respective populations. The correlations tend to be more moderate in the .4 to .5.

Tanya Edie took a very, very small sample of people with laryngectomy and compared speech intelligibility using the sentences to participation and got a very low correlation, which I think speaks to some of what we’re thinking that there’s so much more that influences participation beyond disorder severity that knowing somebody’s intelligibility is not going to determine their self-rated participation. So we have a little bit of that data, definitely more needs to be done.

Kathryn Yorkston:

And it just is teaching us over and over. It’s not just the speech that interferes with participation, it’s the being in a wheelchair and not having the opportunity, it’s fatigue and MS, it’s other things, and if everything related to severity of speech, we would not need to measure participation.

Question: I think you had a slide up there where you were showing the amount of variance that was associated with the global measure from all of these different variables. Are you concerned that the instrument may not be sensitive to the outcomes of speech intervention alone? And then where does that take us with respect to demonstrating the value that we provide as speech pathologists?

Kathryn Yorkston:

I would respond to that is with somebody with MS, I wouldn’t want to do speech intervention and only speech intervention. You know, my mantra is that it really does take a team and that the condition is kind of like a heavy weight on one side of a teeter-totter and we have small weights to put on the other side; better speech, less fatigue, more social support, and if you put enough of those little weights on the other side to tip the balance. So in some situations it, with laryngectomy, you know you certainly would have more of a contribution of if speech improves, life improves. The answer to the question is I think in our intervention we need to measure at all levels to understand the process of what are the active ingredients in intervention? We want to know whether it’s, you know 80% better speech or 20% better speech and 10% decreased depression, whatever.

Audience Comment:

I completely agree with you. Let me see if I can clarify. So for example, the CARE instruments that are being developed by RTI is part of the CMS project to develop alternative outpatient therapy payment models. One of the things that I think they want to do with those instruments is to compare the outcomes and costs of rehabilitation professionals. So compare the outcomes of physical therapist versus occupational therapist versus speech therapists, and their associated costs.

Participation is a huge concept. So I agree with you that all these members of the team are going to be required, perhaps, to see the type of meaningful improvement in participation that we would want as a team of rehabilitation professionals. But how do you show, again, in the context of the limited amount of variance that slurred speech occurred for in your model there, do you have concerns that when speech is looked at independently, that we might not –

Kathryn Yorkston:

I guess I’m, maybe I’m viewing the world through rose-colored glasses, but even if it turns out to be the worst case and that is true, then that would force us to change our model of intervention. To say we’ve got to get out of the treatment room, we’ve got to help the person develop a set of strategies where instead of practicing an hour a day with a speech pathologist, they have a friend that at four o’clock every afternoon they call and just talk. So you know I think it’s almost a win-win situation. We either change what we do, or show that what we do right now works. And either is okay.

Audience Comment:

In a small study I’ve done we found that our impairment level measures dropped off at follow up, but the communicative effectiveness survey that we’re doing, which is the participation measure, did not drop off. There’s much, much more to do, but I was encouraged by those results.

Kathryn Yorkston:

And I think that there’s a certain trajectory. Carolyn, Mike Burns, and I were a part of an aphasia day this June in Seattle, and we had focus groups of people with aphasia. We asked among other questions, what would you tell speech pathologist?

And one of the strongest things in my focus group was, “Tell speech pathologists that we’re still changing years after our stroke. And that’s because I’m becoming more confident, I have more strategies, I do things differently, I have a different attitude.”

So I think we need to kind of broaden our vision of treatment, but at all times we need to kind of understand the relationship. The level of recovery impairment may and certainly, the slope gradually flattens, but the skills that you learn as you live life with aphasia accrue over time.

Acknowledgments

References

Baum, C. M. (2011). Fulfilling the promise: Supporting participation in daily life. Archives of Physical Medicineand Rehabilitation, 92(2), 169–175

Baylor, C., Burns, M., Eadie, T., Britton, D. & Yorkston, K. (2011). A qualitative study of interference with communicative participation across communication disorders in adults. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(4), 269–287 [PubMed]

Baylor, C., Yorkston, K., Eadie, T., Kim, J., Chung, H. & Amtmann, D. (2013). The communicative participation item bank (CPIB): Item bank calibration and development of a disorder-generic short form. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(4), 1190–1208

Baylor, C. R., Yorkston, K. M., Eadie, T. L., Miller, R. M. & Amtmann, D. (2009). Developing the communicative participation item bank: Rasch analysis results from a spasmodic dysphonia sample. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(5), 1302–1320

Baylor, C., Yorkston, K., Bamer, A., Britton, D. & Amtmann, D. (2010). Variables associated with communicative participation in people with multiple sclerosis: A regression analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(2), 143–153 [PubMed]

Baylor, C. R., Yorkston, K. M. & Eadie, T. L. (2005). The consequences of spasmodic dysphonia on communication-related quality of life: A qualitative study of the insider’s experiences. Journal of Communication Disorders, 38(5), 395–419 [PubMed]

Brown, M., Dijkers, M. P., Gordon, W. A., Ashman, T., Charatz, H. & Cheng, Z. (2004). Participation objective, participation subjective: A measure of participation combining outsider and insider perspectives. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 19(6), 459–481 [PubMed]

Eadie, T. L., Yorkston, K. M., Klasner, E. R., Dudgeon, B. J., Deitz, J. C., Baylor, C. R., Miller, R. M. & Amtmann, D. (2006). Measuring communicative participation: A review of self-report instruments in speech-language pathology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(4), 307–320 [PubMed]

King, G., Law, M., King, S., Hurley, P., Hamma, S. . . . Young, N. (2004). Children&s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment & Preferences for Activities of Children. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp.

Law, M. (2002). Participation in the occupations of everyday life. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56(6), 640–649 [PubMed]

Mallinson, T. & Hammel, J. (2010). Measurement of participation: Intersecting person, task, and environment. Archives of Physical Medicine And Rehabilitation, 91(9), S29–S33 [PubMed]

Willis, G. B. (2005). Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Yorkston, K., Beukelman, D., Strand, E. & Hakel, M. (2010). Management of motor speech disorders in children and adults (3rd ed.). Austin, TX: ProEd.

Yorkston, K. M., Baylor, C. R., Dietz, J., Dudgeon, B. J., Eadie, T., Miller, R. M. & Amtmann, D. (2008). Developing a scale of communicative participation: A cognitive interviewing study. Disability & Rehabilitation, 30(6), 425–433

Yorkston, K. M., Baylor, C. R., Klasner, E. R., Deitz, J., Dudgeon, B. J., Eadie, T., Miller, R. M. & Amtmann, D. (2007). Satisfaction with communicative participation as defined by adults with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study. Journal of Communication Disorders, 40(6), 433–451 [PubMed]

Yorkston, K. & Baylor, C. (201). Measurement of Communicative Participation. In Lowitt , A. & Kent , R. (Eds.), Assessment of Motor Speech Disorders (pp. 123-140). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.