The following slides accompanied a presentation delivered at ASHA’s Clinical Practice Research Institute.

Precision and Accuracy

Adapted from Hulley, et al. (2007) .

Just about every statistic (descriptive and inferential) is an expression of a basic ratio.

In the numerator goes a measurement of the influence of the research hypothesis.

In the denominator goes a measurement of the influence of error.

The ratio is very much like signal:noise.

This series of notes presumes a really good research hypothesis and centers on enhancing signal and reducing noise.

Experimental Precision

Experimental precision is closely related to, among other issues, reliability.

Imprecision is brought about by random error.

Enhancing precision is akin to reducing noise in your system.

Sources of random error variance

- Observers

- Instruments

- Participants

Preventative steps (minimize opportunities for chance at play)

- Standardize observation protocols Make the protocols as explicit, simple, and straightforward as is possible

- Standardize interventions (consider a treatment algorithm)

These translate to writing an Operations Manual.

- Train observers and clinicians to criterion

- Simplify all instructions for clarity

- Use pooled observations if possible

- Assess and report reliability within an experiment

Experimental Accuracy

Experimental accuracy is a function of validity

Inaccuracy is brought about by systematic error — AKA bias

Enhancing accuracy is brought about by increasing the signal in your system

Sources of systematic error variance

- Observer bias — e.g., they become more expert with experience, they have knowledge of the hypothesis

- Instrument bias — e.g., ceiling or floor effects, under representation of construct

- Participant bias — e.g., selection bias, differential attrition, compensatory rivalry, maturation

These are nothing more than Cook & Campbell’s (1979) various threats to experimental validities.

Preventative steps (minimize opportunities for chance at play)

- Parsimony in admitting variables into an experiment and calibrate instruments

- Streamline and standardize observation and intervention protocols

- Make unobtrusive measurements

- Take great care forming a protocol for participant selection

- Take great care forming a protocol for participant allocation

- Take great care forming a protocol for interim analyses

- Blind as possible

Graphical Examples

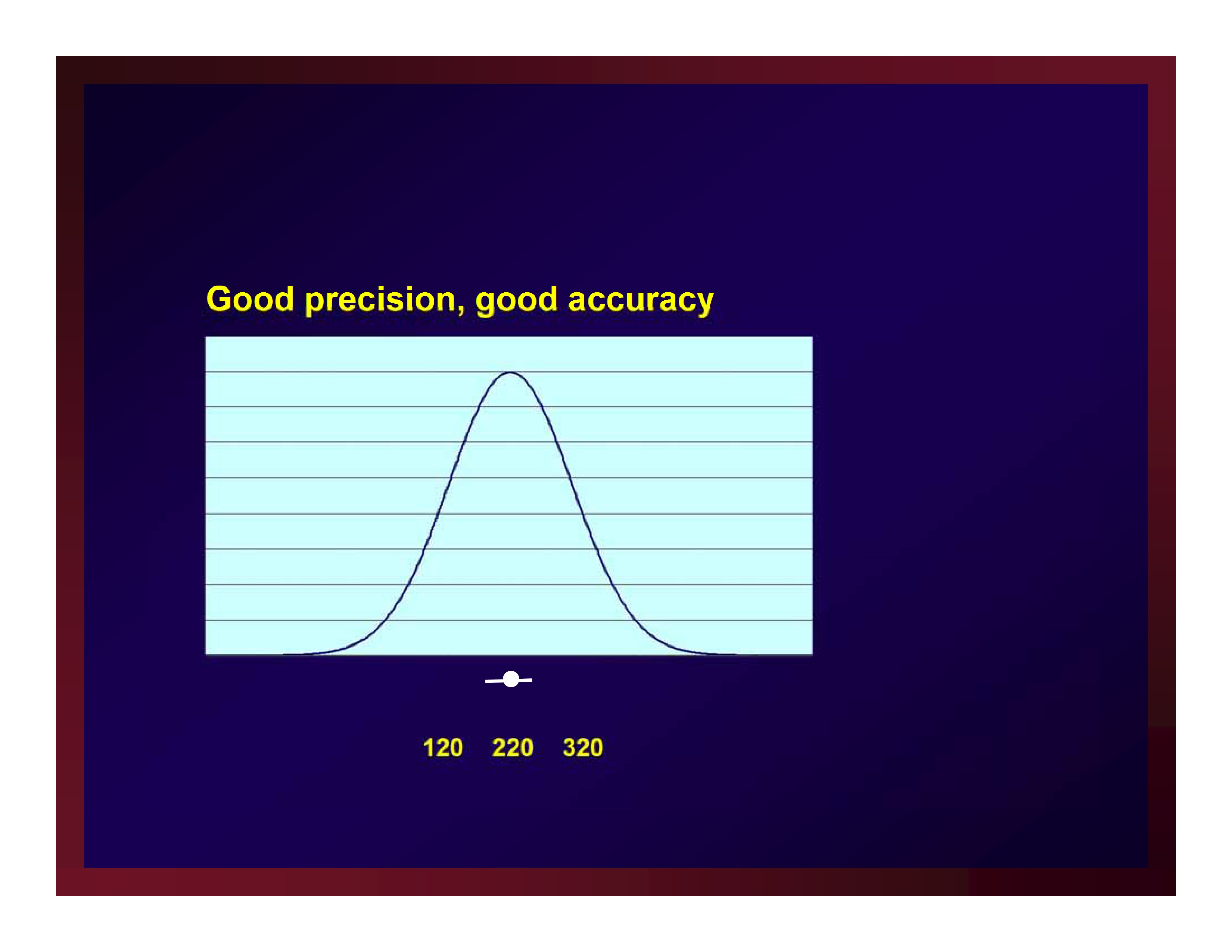

Good precision, good accuracy

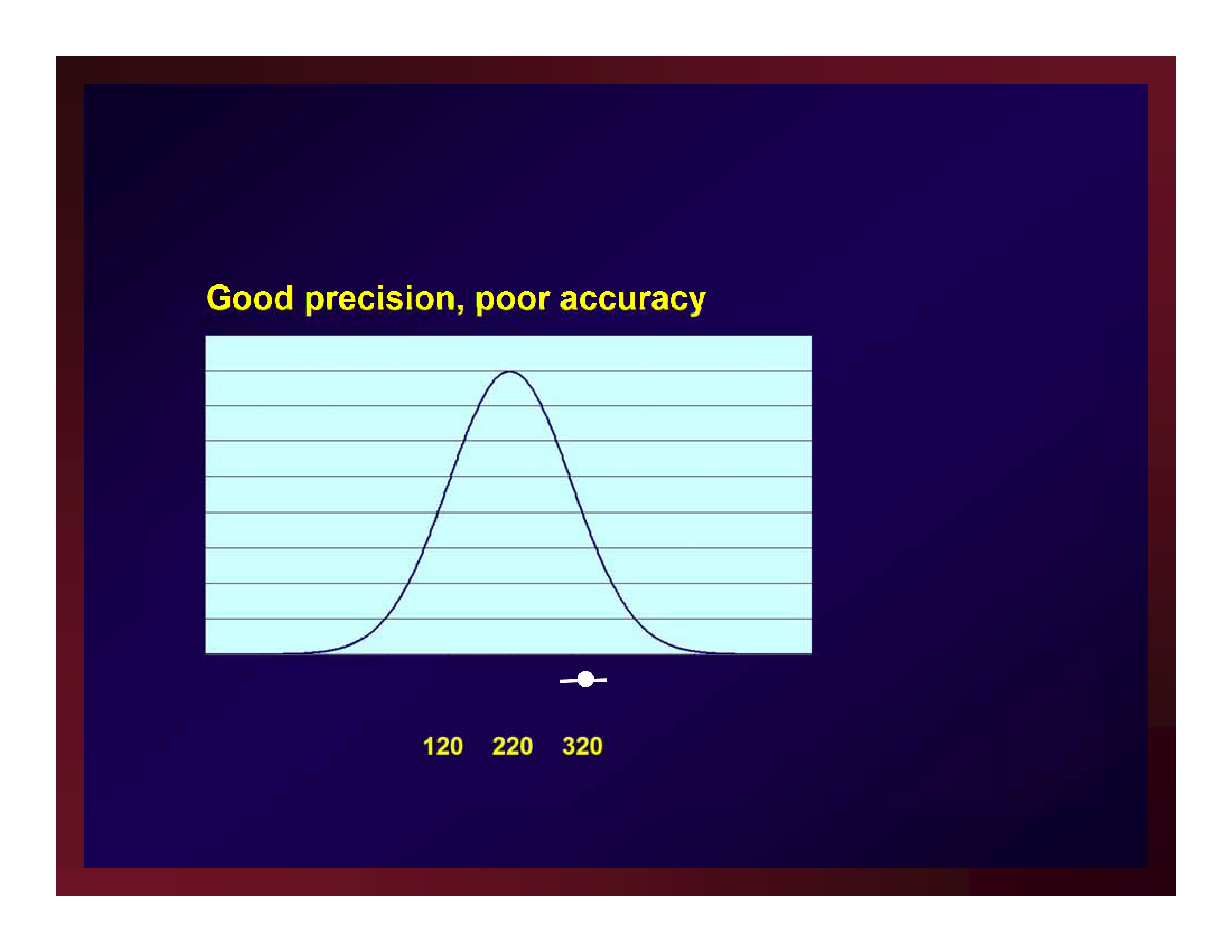

Good precision, poor accuracy

Good precision, poor accuracy

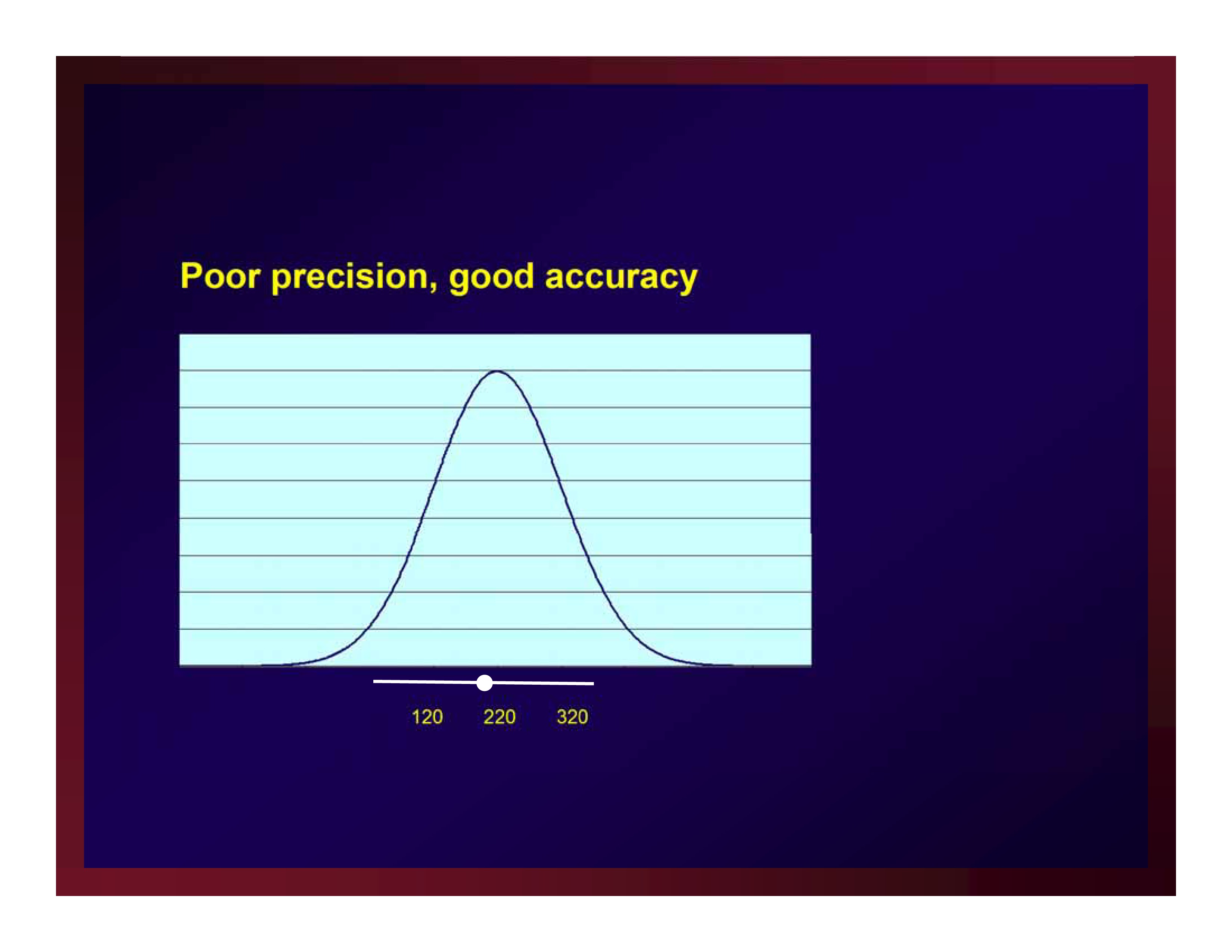

Poor precision, good accuracy

Poor precision, good accuracy

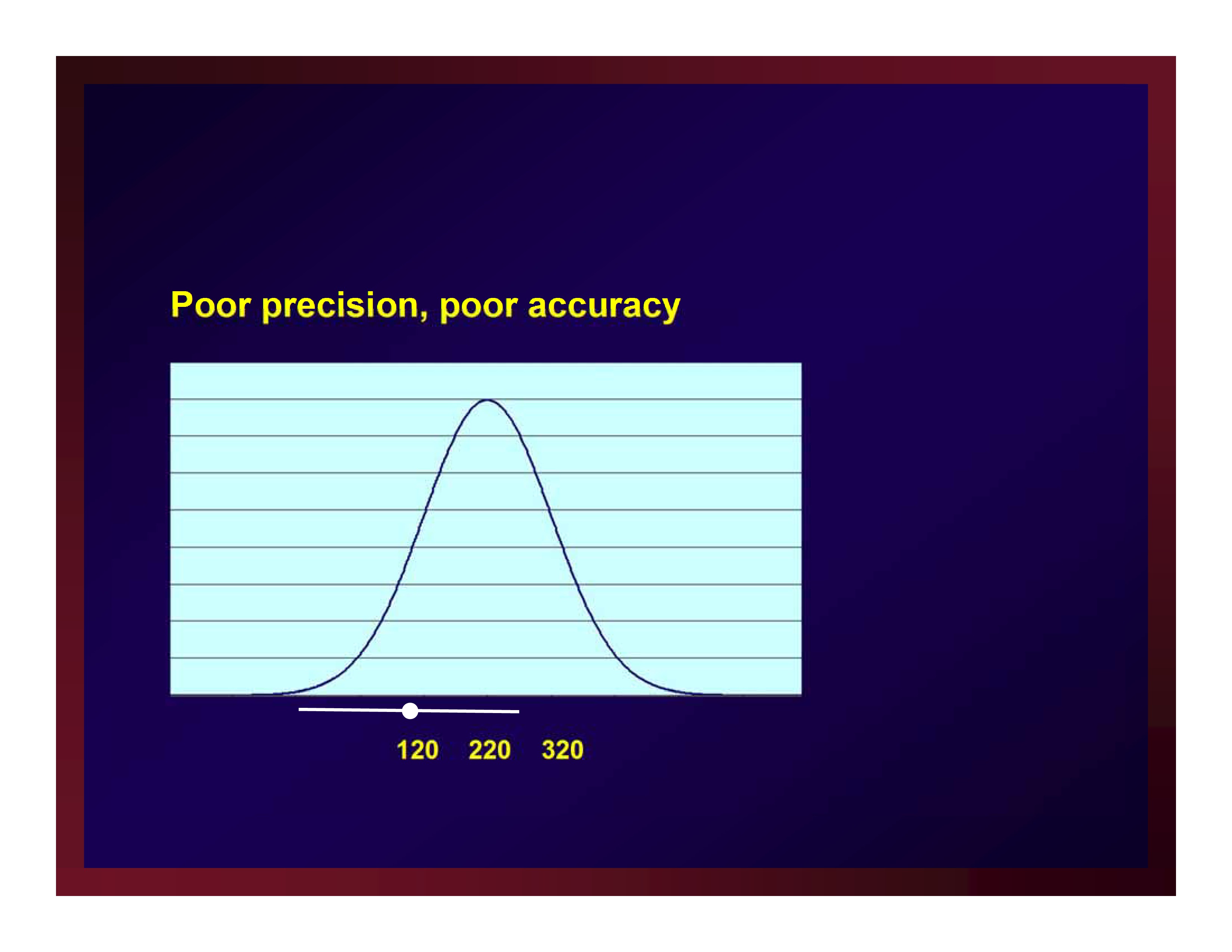

Poor precision, poor accuracy

Poor precision, poor accuracy

Confounds and Effect Modifiers

Confounds and Effect Modifiers

Adapted from Portney & Watkins (2009).

That which is screwed up in design cannot be fixed through analysis.

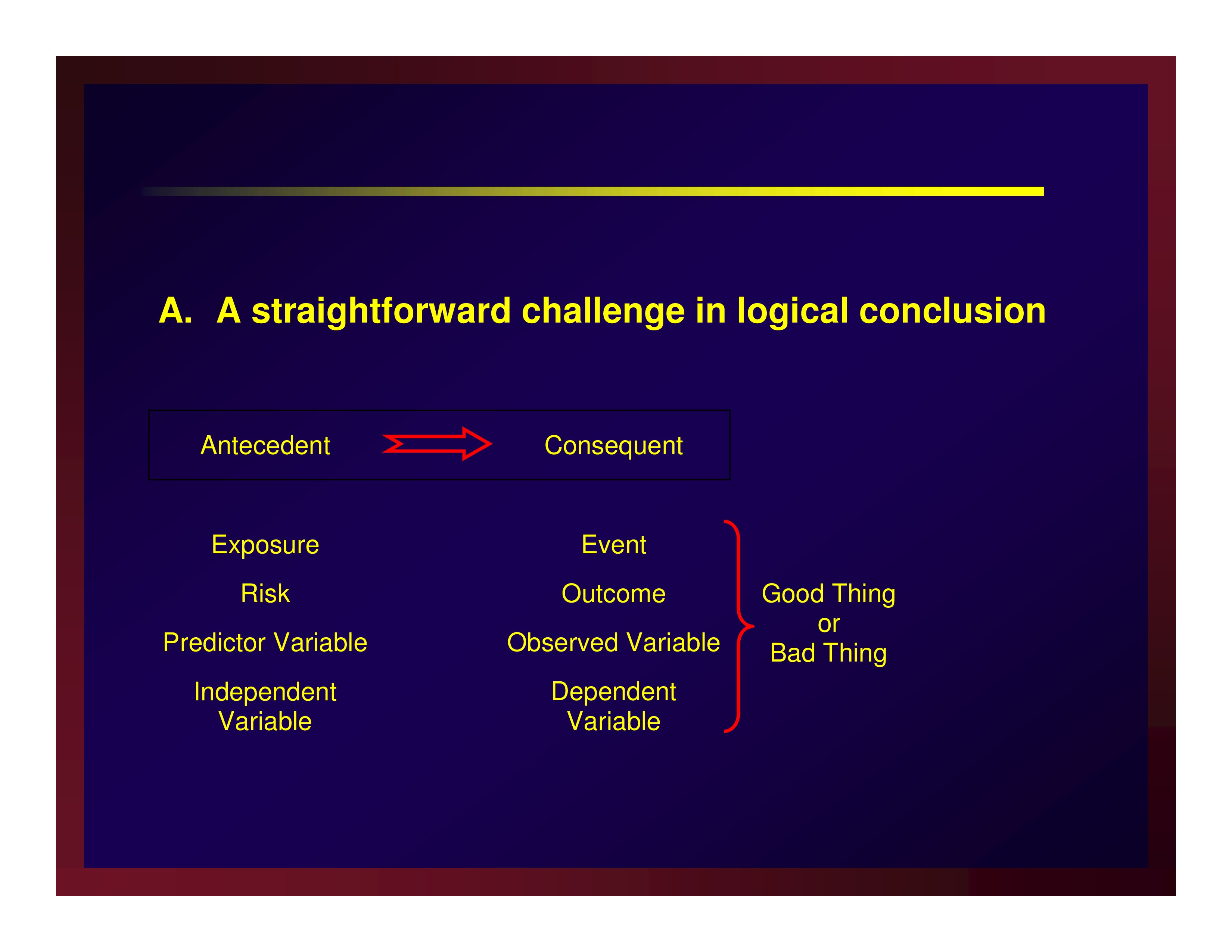

A straightforward challenge in logical conclusion

Confounders and effect modifiers make rival explanations for the results

Confounders and effect modifiers make rival explanations for the results

AKA a threat to internal validity

Confounders

A confounder is an extraneous or nuisance variable

- It is associated with the antecedent — co-occurs to some extent

- It is associated with the consequent – exacerbates or suppresses the outcome

Confounders are fundamentally the threats to internal validity first described by Cook & Campbell (1979)

- Under representation of the population

- Misrepresentation of the population

- Allocation Imbalance

- (Differential) history

- (Differential) maturation

- (Differential) testing

- (Differential) regression

- Diffusion of treatment

- Compensatory equalization of control treatment

- Compensatory rivalry

Effect Modifiers

Effect modifiers are not a nuisance; they are not extraneous

Effect modifiers are variables that moderate the relationship between antecedent and consequent

Remedies

Requires a priori identification of potential confounders that are measured for later uses needed.

- Unbiased recruiting independent of assignments

- Random assignment

- Monitoring and breaking protocol

- Representativeness

- Blinding (as possible)

- Participant

- Clinician

- Analyst

- Intention-to-treat analysis

- Completer analysis

- Non-completion = fail

- Last observation brought forward

- Persuade a return for post testing only

- Matching

- Narrow inclusion criteria

- Stratification

- Analysis of covariance

Resources for Assessing Quality Indicators

Case Reports and Case Series

Jabs, D. A. (2005). Improving the reporting of clinical case series. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 139(5), 900–905 [Article] [PubMed]

Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2001). In defense of case reports and case series. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(4), 330–334 [Article] [PubMed] Cross Sectional Designs

Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM). (2007). STROBE Checklist for Cross-Sectional Studies. STROBE Statement (Available at www.strobe-statement.org).

Case Control Designs

Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM). (2007). STROBE Checklist for Case-Control Studies. STROBE Statement (Available at www.strobe-statement.org).

Cohort Designs

Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM). (2007). STROBE Checklist for Cohort Studies. STROBE Statement (Available at www.strobe-statement.org).

Parallel-Groups RCTs

Moher, D., Schulz, K. F. & Altman, D. G. for the CONSORT Group (2001). The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 1(1), 2 [Article] [PubMed]

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). (2010). CONSORT Website. (Available at www.consort-statement.org).

Parallel Groups CTs

Des Jarlais, D. C., Lyles, C. & Crepaz, N. for the TREND Group (2004). Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. American Journal of Public Health, 94(3), 361–366 [Article] [PubMed]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND). (Available at www.cdc.gov/trendstatement).

Cross Over RCTs

Senn, S., (2002). Crossover Designs in Clinical Research. Wiley

Single-Subject Trials

Chambless, D. L. & Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 7 [Article] [PubMed]

References

Cook, T.D. & Campbell, D.T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Hulley, S., Cummings, S., Browner, W., Grady, D. & Newman, T. (2007). Designing Clinical Research. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Portney, L.G. & Watkins, M.P. (2009). Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice (3rd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.