Successful careers in academia start with the sage advice of our mentors and advisors. Many of us can recall hearing friendly reminders, such as, “Negotiate the best teaching load that you can when you start your career; you’ll need time for research” and “Longitudinal studies aren’t the best way to start your career in academia. You won’t have enough data for publication in the timeframe under which you’ll need it.” These sage words make a great deal of sense when one considers the life of the early academic. However, over time, the discipline has evolved, and with that evolution come new perspectives regarding the start of a research career, tenure, and subsequent promotion.

The past decade has brought with it an ever-increasing demand for clinical accountability and the use of evidence-based practice (EBP). This demand has increased the need for researchers to conduct clinical practice research (CPR), which addresses issues surrounding service delivery methods and outcomes (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2014). In contrast to research focused on better understanding mechanisms underlying normal or disordered processes, CPR goals are more directly related to client outcomes. CPR is essential to help clinicians better serve clients; however, inherent in traditional CPR approaches are features that may seem incompatible with the academic timeline of a tenure-track assistant professor who typically has 5 years to demonstrate the development of a high-quality research program. Thus, the question becomes, “Should the assistant professor develop a research program based on CPR or wait until after earning tenure?” There is no easy answer to this question. Addressing challenging clinical issues affords the new faculty member an opportunity to make a meaningful impact on the field. Still, there are potential significant obstacles that require careful consideration before an individual pursues a CPR program of research:

- the “value” of CPR at a given institution and how CPR fits into institutional requirements for tenure and promotion

- the explicit need for CPR in the discipline and how that might be supported by reviewers of a tenure dossier

- the number of venues available that review, accept, and publish CPR

- the likelihood of publishing negative study results

- the number of participants required to demonstrate a clinical effect

- the availability of participants, especially if CPR targets a relatively low-incident population

- the availability of financial resources and time for longitudinal intervention studies

- the need to develop community partnerships to support study recruitment, evaluation, and implementation

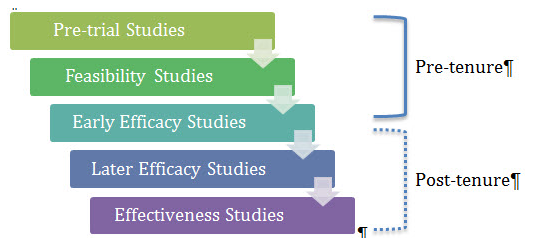

These are formidable factors that might stop the new academic from engaging in CPR. Yet, the potential also exists for an early career researcher to make significant positive impacts on a discipline that may forward a career or possibly even jump-start the faculty member’s recognition within the discipline. Keeping sight of these important benefits, we propose that an assistant professor can, indeed, be successful in CPR and the tenure process with some thoughtful planning and consideration. For example, a supportive mentor could help the junior researcher develop a research plan using the following model, which is based on the work of Fey and Finestack (2009):

With this model, we consider the broader arc of CPR and how it might fit across the career of the academic researcher. In this figure, the solid bracket captures activities that could occur during the early phases of a research career, including pre-trial studies, feasibility studies, and possibly some early efficacy studies. Study designs for these types of studies are well suited for assistant professors for several reasons. Such studies may be conducted using non-affected populations, require fewer participants, have surrogate end-points that reduce the study length and cost, and have greater experimental control, which increases acceptability for publication. CPR at these levels generally requires less time than large-scale effectiveness studies and results in a series of publishable experiments that prepare for future larger-scaled studies. The dotted bracket captures studies that may be better suited for tenured researchers who have the flexibility to take more risks with their research. Without the stressors of tenure, senior researchers have time to examine efficacy and effectiveness of their clinical research practices outside the laboratory environment.

This leaves the question: Is CPR detrimental to the career of the new investigator? It likely depends on the chosen/assigned mentor, the institution where the researcher is located, and the potential impact of the research in question. However, the authors concur that CPR need not be dismissed out of hand for the new academic. For the assistant professor who wants to engage in CPR, it will be important to design a strategic and savvy program of research that follows a stage-wise progression as he or she simultaneously moves through the professional ranks. With thoughtful advising, prudent mentoring, and a systematic approach, the new investigator can conduct research which feeds the future of CPR and could well set the stage for a successful and satisfying career.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2014). Clinical Practice Research Institute. Retrieved August 29, 2014, from http://www.asha.org/Research/CPRI/.

Fey, M. E., & Finestack, L. H. (2009). Research and development in children’s language intervention: A 5-phase model. In R. G. Schwartz (Ed.), Handbook of child language disorders (pp. 513–531). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Resource

Robey, R. R. (2004). A five-phase model for clinical-outcome research. Journal of Communication Disorders, 37, 401–411.