The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Getting Started

We’re going to start with an overview of grantsmanship tips.

Preliminary Planning

Elena Plante:

Getting started: the idea here is that grant writing starts long before you sit down and put your fingers to the keyboard.

I generally take a month to write a grant for the actual writing process. However, my planning process going about a year ahead of what the deadline is.

Some of the things you want to consider: What are your institutional priorities? That might shape what kind of a grant you should be going after.

For example, my institution really does not like to waive overhead costs. They really don’t. They’ll do it if you’re junior faculty, but once you’ve got tenure, they don’t want to see those kind of grants come across their threshold from you. These are the kinds of things you should know about your institution that might affect what grant you’re going after.

You want to define the scope of the problem. This is a challenge area for some people.

And then, one of the things I do a year out, is I sit down and make a priority list for the year. And one of the things that shapes this is what grants are going out. Because those are the papers that have to come out first to support that grant submission. I do that a year in advance.

You want to identify what expertise you need for the grant, and get either your co-investigators or your collaborators on board, well in advance, so you know you have the expertise to move forward. Some of these might be internal, some of them you may need to go to another institution to line up that expertise, if you don’t have that locally.

And finally, determine what additional resources you need, either from your institution or from collaborators.

We heard this morning about getting an external review, either from somebody outside your department or maybe outside your institution. And we heard one example of somebody being paid within their own institution. When I was a department, I hired people outside my institution to do a grant review of junior faculty when they’ve already gone in once, to help them negotiate their reviews and up their probability of success a second time.

These are things you want to be thinking of well in advance.

Mario Svirsky:

Let me interject something. The way we’re going to do this, by the way, Elena is going to give this talk, and every so often I’m going to add something.

So about people who read your grants. If you give someone your grant to read a month before the deadline, that’s absurd. You need to give someone a couple of weeks to do a good job and to read the grant. And it’s quite possible that they’ll say, “This specific aim is all wrong. You need to delete this experiment, and you need to write a lot of new stuff. So you need time to react to that. That means at least a couple months in advance, if not more.

Elena Plante:

Another thing to consider is to have a couple of levels of review built in. I often send out my aims before the rest of the grant is written to a couple of people, and have them look at it. If those aren’t going to fly, I need to know that right away. And I can be working on other sections.

Another thing that I do is I send a list of questions with the section I’m sending out. And if they can’t give me back what I intend that section to reflect by answering those questions, I know I haven’t targeted it right.

I wanted to point out, and we say this all the time, is that people who get grants write lots of grants. They also re-write lots of grants.

We’ve already heard, “Don’t take it personally if your grant doesn’t get funded the first time.” For those of you who are lucky enough to get a grant funded on the first time, my advice to you is sometimes you get that first grant not because of what you did, but in spite of it. And then that second grant hits you like a wall of bricks. Don’t be afraid of that process.

And don’t make grant writing a special event. Right now, I have two grants funded, I have two in review, I’m writing two, and I have two in the queue. I’m not PI on all of these grants, I’m PI on about half of them. But the point is, grant writing is not a special event for me. I write grants all the time. That’s why I’m funded all the time.

Again, planning, you want to find your funding source. In the next couple of days you’re going to hear from a lot of funding sources beyond NIH. And get information from the program officers. Program officers, their job is to talk to you. That’s their job.

Don’t hesitate to talk to them if you’re putting in a grant. If you’re thinking about putting in a grant, they’ve got great advice about how to focus things, and what kind of things will head something to one Institute versus another.

There are a lot of online resources.

Mario Svirsky:

You need to know your program officer. Be respectful of their time, because they are extremely busy, but those few minutes of conversation that you’ll spend with them are extremely important. You should be ready to talk to them. You should have some idea about specific aims. You should be able to pitch your grant.

You should have pitches at several levels. There’s the two-phrase description, the 30-second description, the two-minute description, and so on.

Elena Plante:

You want to check your schedule for commitments relative to the due date. Because you cannot have major things happening around the due date. That’s just not going to work.

This is the best way to keep other people off your back. Say, “I’ve got a grant deadline.” And everyone will back out. Just make it public that you’re writing a grant.

And allow time for the university process. This is going to be different at every institution. At my institution, they will not accept a grant more than three days out from the actual due date because it takes them that long — and trust me, the websites for the actual grant agencies get busier, and busier, and busier the closer you get to that final hour. You do not want your grant going up in the last couple of hours of the due date. Because the chances of a backlog happening are just too big.

Mario Svirsky:

The main thing about the grant is the intellectual content, right? The research program and all that. But your grants office wants to see everything, all the administrative details. They want to see the budget. And you can have all the other stuff ready easily a month in advance, and they will review that stuff for content, even with the research plan is not necessarily final.

So there’s no excuse for not sending that draft that’s near-final for the research and had all the rest, well in advance.

Remember that the NIH deadlines are the same for everyone — for all the professors in your university, so that office will be completely overwhelmed when it gets to be three days before the deadline.

Elena Plante:

So the first piece of advice is follow the instructions exactly. I sit on an NIH review panel. I know Mario does also. Several people in the room I know do. And I can’t tell you how many times we see grants where the directions aren’t being followed. And trust me, we see a lot of grants in a year, so we know exactly what’s allowed in every section.

If you’re not following it, the first thing that occurs to us is like, “Well, if they can’t even follow the instructions, how much detail are they going to attend to in their project?” So, I shouldn’t have to say this, but apparently I do.

The next thing is to understand the review process and help the reviewers advocate for your grant. Over the next three days, you’re going to see the review process in action. You’re going to hear more about the review process, you’re going to hear about responding to reviews. You’re going to hear from program officers about reviews. You’re going to hear a lot about it. So I’m going to be a little bit brief here.

And the first thing to realize is who is reviewing your grant. A lot of people who are new grant writers think that it’s going to be experts in their area. That’s only partially true. That may happen, you may be the lucky one who gets the expert in your area reviewing your grant.

I’ve been on the LCOM panel for several years now. I can tell you, my population where my most expertise is specific language impairment. My first two years of reviews, there were plenty of grants on specific language impairment — and I did not review a single one of them.

I reviewed auditory habilitation. I reviewed autism. I reviewed cochlear implants. I reviewed all kinds of things that I really did have relevant expertise for, but they were not my primary area of interest. So you have to bear in mind that you are writing for a smart, educated scientist who is not necessarily the expert in your area. So if your grant did not do well in specific language impairment, it wasn’t me. I was in auditory habilitation, I’m sorry.

You need to make a grant understandable by people who are smart, who are good scientists, who know scientific principles, but may not have the specific expertise that you have.

The other thing to bear in mind is that the people who review your grants — they have a day job. And it’s not reviewing your grant. When does your grant get reviewed? I don’t review grants during the day. I work my job during the day. So then I go home. And then I deal with household stuff. And then some time in the evening, I start reviewing grants. So if you’re the lucky person that I start your grant at 9:00 at night, and I may get through half of it, and then I pick it up the next night at 9:00, I’m tired. You need to help me help you. And the rest of the talk, basically, is about how you can help me help you. Because I want to help you, but if you make it hard for me at 9:00, you’ll make me cranky. And that’s not the state you want me reviewing your grant in.

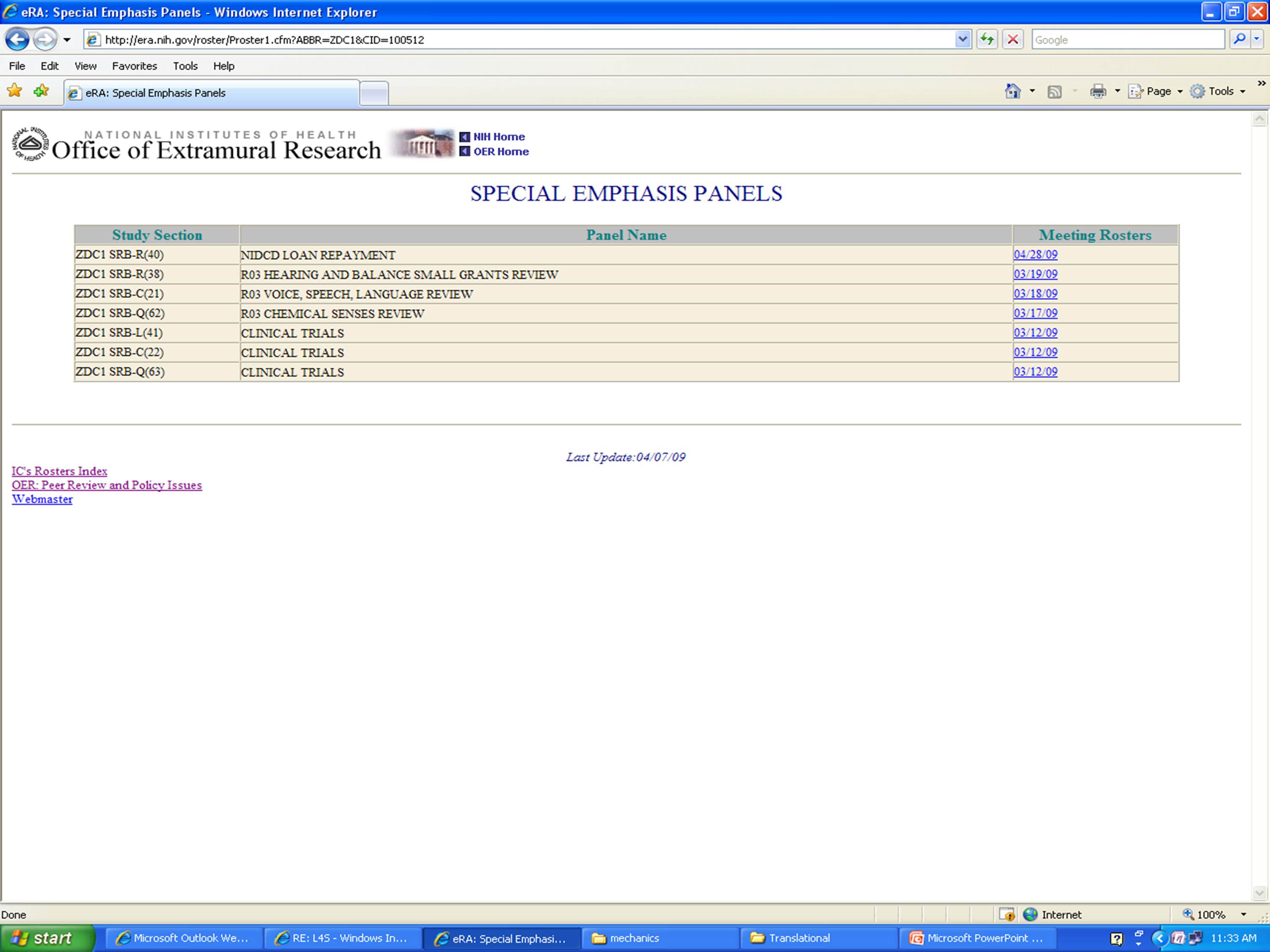

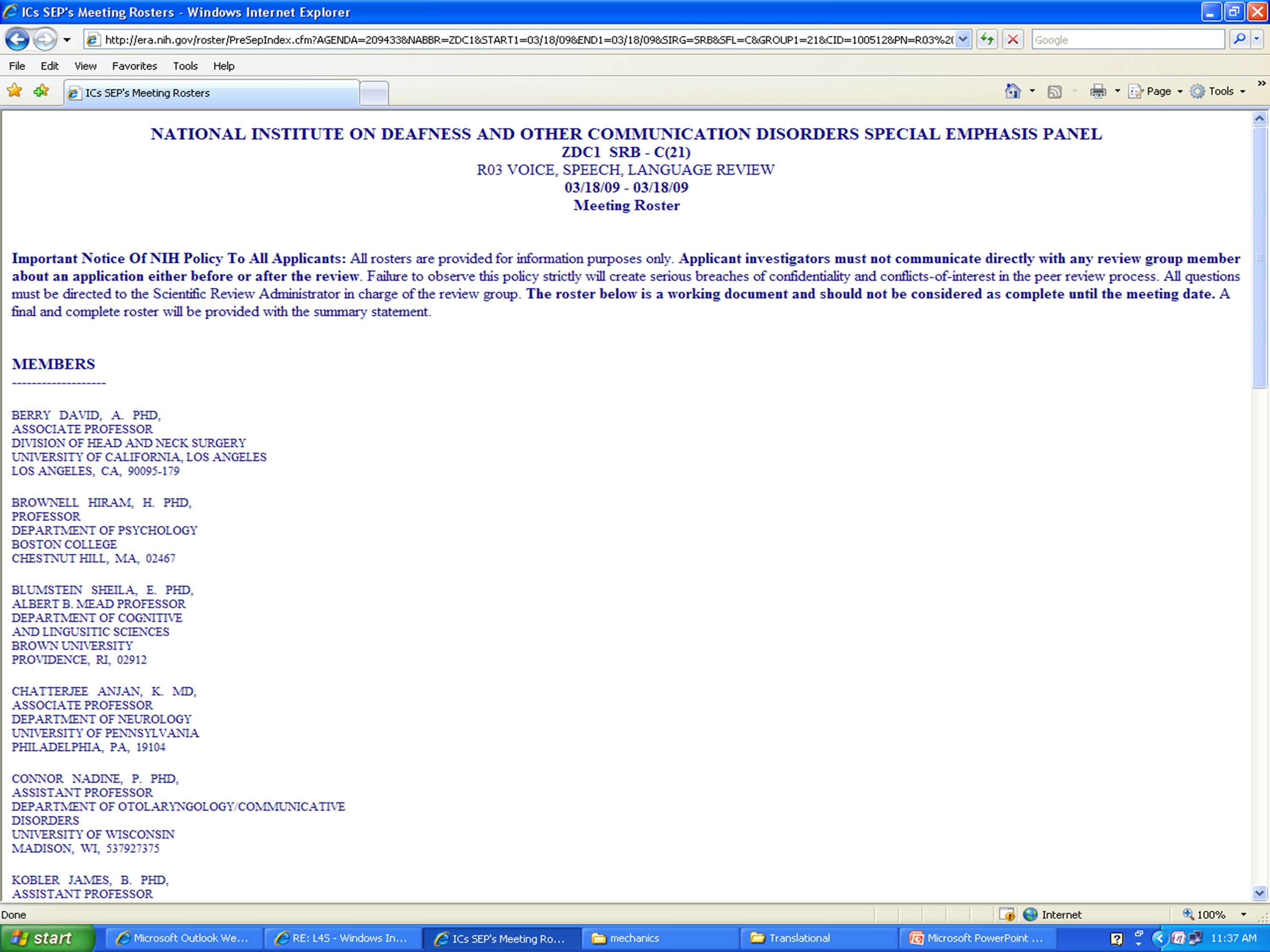

The other thing about reviewers is that you can find out who they are. Most of the time. Unless you go to special emphasis panel, you can find out who they are. The NIH has a webpage, and you can actually find out who the standing panel members are for the panels that your grant will go to.

One of the things that you get told by the NIH is that when you write a cover letter, you might suggest which panel might be best suited for your grant. You can look and see who is on that panel. And these are the standing members that will be reviewing — they might review three times a year, they might be reviewing two times a year. So you don’t know exactly who is on that panel, and you certainly don’t know who is going to be assigned your grant. Even if the logical person for your grant is there, it doesn’t mean that they’ve got your grant.

Mario Svirsky:

One thing you will see there is that there will be links for the study section roster, which is composed of permanent members of the study section. And then meeting rosters, which lists the people who actually participated in a given session. That includes permanent members as well as ad hoc member who participated, maybe via phone or for just a few grants. So keep that in mind.

Elena Plante:

It’s not really feasible to write to a specific reviewer. But if you look at the panel, and you know that there’s a certain theoretical perspective out there. And your grant doesn’t have that theoretical perspective. You might be a little strategic about justifying why you’re taking this approach and not that approach.

And certainly if you know you’re publishing in an area where there’s another person on the panel who is publishing a lot, you probably want to understand what kind of papers they’ve been publishing because that tells you something about their general viewpoint. You can use this as an orienting kind of activity. But again, you can’t write as if you know who’s going to get your grant. You just won’t know that.

Mario Svirsky:

But getting the right study section can be extremely important. Sometimes because of the subject matter, it’s very clear that your grant should go to this particular study section. There’s other situations where it’s not. Let’s say you’re submitting a grant about the influence of speech perception on language development in cochlear implant users. Is that hearing? Or is that language? You could argue it either way. So you should consult with your colleagues to see which study section is most likely to understand your proposal better and to have a higher likelihood of success.

Elena Plante:

Again, your program officers are often sitting in the room during these reviews. They will know a lot about the study sections and what might be better for you to head your grant towards.

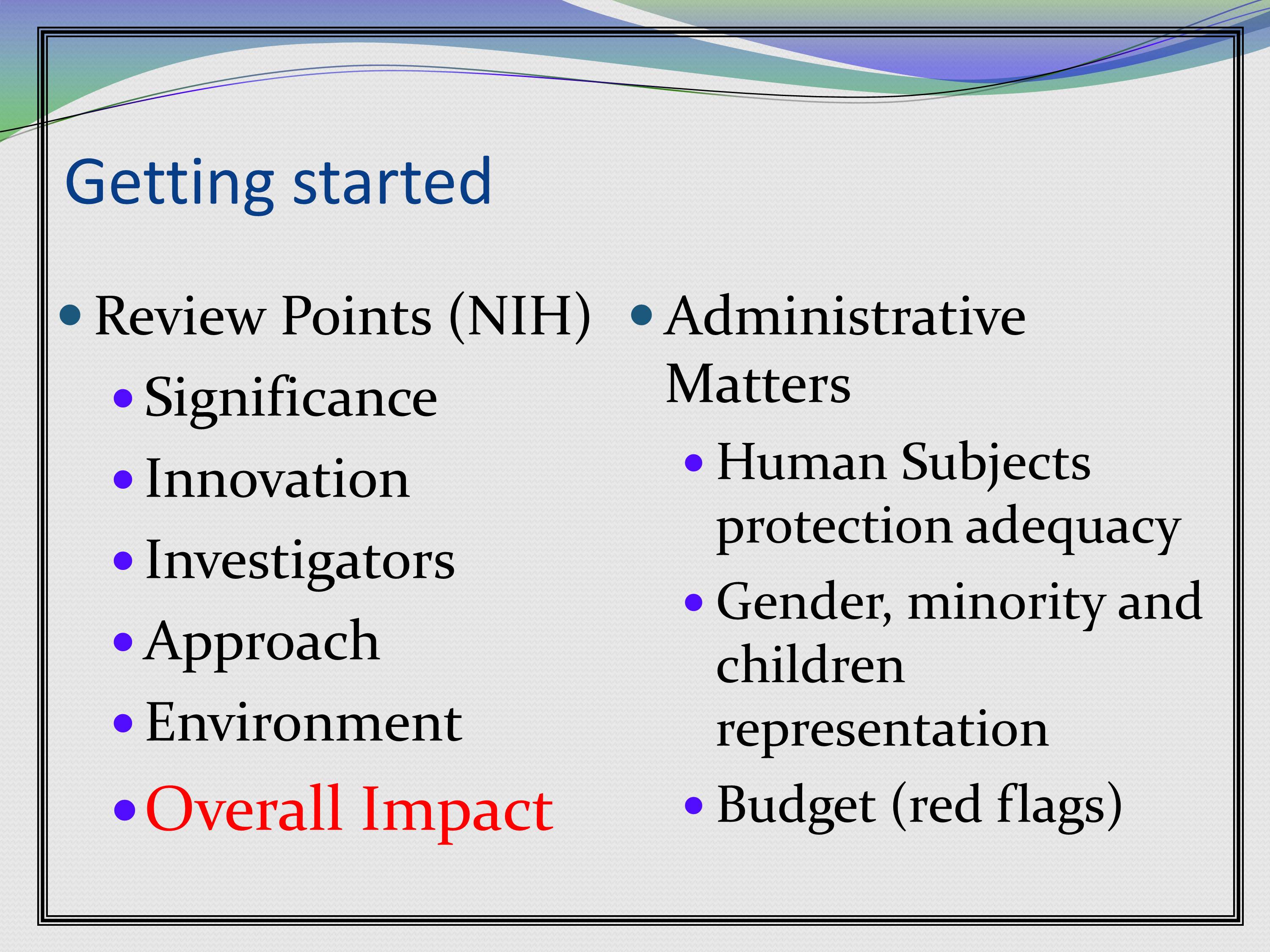

So last. Write to the review criteria. In the NIH, the review criteria are available on their website. You can look them up and tell what we’re scoring. They basically follow the headers of the grant.

Other grant agencies, like you’ll hear from the guy from NIDRR. They tell you to use the review criteria as a header, but they don’t give it to you as a format. I’m probably the only child language researcher in the world who was funded for their doctoral research by the US Air Force. Basically, I did that, I wrote to their review criteria, and that decided they needed to fund a child language researcher.

Write to the review criteria. Use the review criteria as headers. NIH will actually do that for you. And use the terminology in the instructions, because that’s what they’re looking for.

I’m tired and going through it, and I’m looking for “innovation” and “significance” — there is wording in the review criteria where, if I see it, I go, “Thank God, there it is.” And then I can lift it out and smack into my review. You’ve done the work for me, now I’m really happy with you.

Here’s the review criteria for an NIH grant. We give section scores for the significance, innovation, investigators, approach, and environment. These are all headers in the grant format.

However, the score that gets you to the table is the “overall impact.” This is not an arithmetic average of the rest of these scores. It’s not. It has to do with our perception of how big an impact overall this research is likely to have on the field.

The wording is, is it going to produce “a sustained and powerful impact” on the field. Sustained and powerful. That’s what we’re looking for.

Then there are some administrative matters that we go through. Frankly, if these areas are weak, they will affect our overall impact score, but they don’t get scored.

Again, the overall impact score the wording in the review criteria is the assessment of the likelihood for the project to exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved. That’s the target you’re heading for.

I’m going to quote Mario, because he said something brilliant last year. That is, “The NIH doesn’t support good research. They support excellent research.”

Writing and Overall Layout

So in terms of actually getting your fingers on the keyboard and getting the grant banged out. One of the things you need to do is establish some writing roles. If you’re writing the grant, you’re writing the whole thing, that’s great. You’ve got all the roles.

But if you’ve got collaborators involved or co-investigators or whatnot, you might want to divvy up the jobs to other people. But it’s really important that your grant read as though it was written with one voice.

That means that if you’ve got pieces coming in from other people, you’ve got to also allocate some time to make sure that you’ve got those things integrated such that you have a grant that reads with one voice.

Use your consultant expertise up front. It is not good enough to slap the biosketch in there and figure you’ll work it all out on the back end. Because if you have a consultant, but his expertise is not represented in the grant, we’re going to question whether you have a working relationship with that consultant, and it’s not going to do you any good. In fact, you may be worse off than you were before.

Mario Svirsky:

I’m willing to bet that all the senior faculty have had the experience over the years of getting a phone call or email a week before a grant deadline from a colleague asking them, “Hey would you be my consultant for this grant?” That’s happened to me a few times. Those grants never get funded.

Elena Plante:

We’ve already heard to allow enough time for writing. Set some timelines for your writing. Give yourself deadlines. Part of the problem with academic life is that there are really very few deadlines except for the great filing day. Other things just kind of roll along. So make yourself some deadlines. And make them hard. And then hit them.

Give collaborators and others time to read and edit. Mario’s already said that. Our morning speaker said it.

Get an outside review. Again, you’re going to hear this over and over again.

Review by section. Don’t give a person a whole grant. Frankly, these days, 12 pages for a body of a grant is not an onerous read. Six pages I like even better. But you can give somebody your one-page abstract, or your one-page aims, and that’s not a hard thing. And then you owe them.

Finally, have everybody in your lab review every single grant that goes out the door. This is the only way people get exposed to the format. Like any other narrative format, the more exposure you have to whatever it is, the better you are at writing them.

One thing that’s really critical is to get models of funded grants from your colleagues. It doesn’t even matter if they are right in your area. They have to be close enough so that you understand, “Oh, I see how the argument is building here.” A great grant can be read by anybody. However, the requirements for NIH changed in 2010. So make sure you have a relatively recent one. There are still grants out there that are funded, that are still under the old format. We’re getting close to where that’s no longer going to be true, but just be cautious about that.

Format for readability. First thing, again, is follow the directions. A lot of grant agencies have requirements for fonts and margins. Follow them.

Use headers and spacing. One of the things I hate to see at 10:00 at night is a wall of words. Even if you put a point 6 space between every paragraph, I know visually I have a place to take a breath. That’s really important, believe it or not. Use headers and spacing so I can follow along where I am. Avoid abbreviations and acronyms. And I know some of you in this room are guilty because I read those grants.

Mario Svirsky:

I want to make a comment about headers and spacing. You should use all the 12 pages or 6 pages that you have. Use them to increase the spacing and make the grant more appealing. And it’s not just because when you get cranky, you’re reading these grants at the end. But also during the actual discussion of the grant — it’s maybe 15 minutes, tops. So if somebody has to go to bat for your grant to say, “No, no. He did say this. I have it right here. It’s really good if they can go to the right point. If you have that wall of words, it’s impossible to find anything. That’s another reason why this is important.

Elena Plante:

Let’s go through acronyms, my own little pet peeve. Because I’m old, your grant should not be a working memory problem for me. Especially if I started your grant at 10:00 pm, and I didn’t get back to it until the next night, I can’t remember what your acronyms are.

Good acronyms are ones that everybody knows what they are. dB SPL. ADHD, that’s a good acronym. NIH, another good one.

Bad acronyms are specific to your field. Why is that? Because I’m reading aural habilitation grants, that’s why. Although I know a lot about treatment research, I don’t know so much about hearing loss.

Let’s take poll here. How many of you know what NWR is? Raise your hand. That’s a third of you. How about IFG? That’s a little bit better, a little over a third, not quite a half. Which means half the room is in the dark.

Now, really bad acronyms are specific to your grant. How many people think they know what a YC is? One, two. How about a VWM-HL? I pulled this out of a grant. Yeah, there’s the problem. Researchers do not want to search for your acronym definitions as they read. Because the way the PDFs are set up, you lose your place, you can’t get back to it easily. Now I’m really cranky, and you have not helped me.

Format for skimmability. I’ll just reinforce what Mario said. It’s really important for your grant to be skimmable. Because we may have read it a month before we all get to the table. I don’t have time to do things twice. I’ll review your grant once. Then I’m going to skim it before the discussion comes up so I can reload it in my memory, but I’m not going to re-read it in detail. Unless your grant is skimmable, and I can find the major points — I cannot help you as much as if it is.

Tables and figures are really good. Highlight the critical elements in your grant so I can find them easily.

Here’s an example of a type of header that somebody uses so that it really jumps off the page. So that things can be found.

This was a tip from someone who put in appendices. She puts the letter of the appendix down the margin so you know which appendix you’re on when you’ve opened it up.

However, there’s a caution about the appendix: Raise your hand if you review grants. Now keep your hand up if you routinely read the Appendix.

There you go. Most people are not opening those appended materials. You cannot use the appendix to supplement the page limits of the grant. And most people are never going to access them. Never.

So be careful about your use of appendices.

Audience Comment:

I want to add, I’m one of the people who looks at them, but if they are more than supplementary, if they are part of the content of the grant, I will discount that. Basically, that’s illegal in the system.

Mario Svirsky:

The different parts of the grants have very different likelihoods of being read. I would say the specific aims and abstract are the parts that most people in the study section read. Because you have to vote on everything, even if you are not a reviewer. So those are extremely important.

Figures and tables have a high likelihood of being checked out, at least.

Appendices are the least. As a reader, I sometimes see that they make a reference to a paper, and I may go read that paper, but that’s kind of above and beyond. Because it’s late and I’m cranky.

Elena Plante:

And it’s not like I just have your grant to review. I have a stack of grants. The chance that I’m going to go above and beyond to read appendices and citations — no. Slim to none.

Mario Svirsky:

So saying that “the methods were described in my JASA paper.” Come on.

Project Description (Abstract)

Elena Plante:

The project description or abstract, as Mario just said, might be the only thing that people at the table read. They weren’t assigned to the grant, so they are just getting the overview before people start the discussion. Also, this gets posted to the public website. So you really want to do a good job of this. It makes the first impression. It should reflect the long term goals. It should highlight the nature of the proposed research. And, this is really critical, make a strong case for the importance of the work.

Getting back to that review criteria: Is it going to make a sustained and powerful impact on the field? You want to start off with a bang and show in your abstract that that is going to be the case.

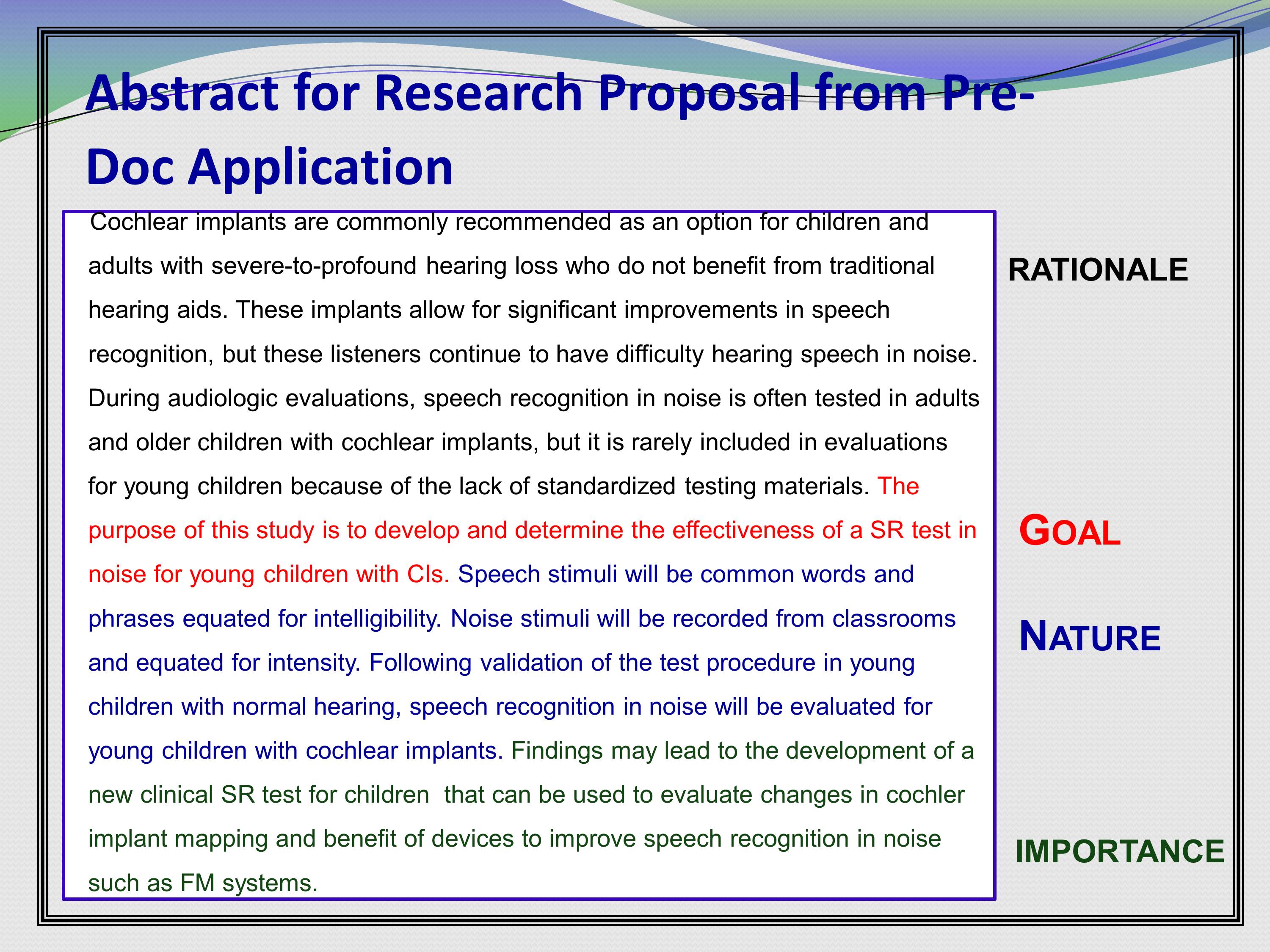

Here’s a dissected abstract. This came from an F31. It basically lays out the information like this.

They have a rationale up front. It has about three sentences.

“Cochlear implants are commonly recommended as an option for adults with severe to profound hearing loss.” Now we know who the grant is going to focus on.

“These implants allow for significant improvements in speech recognition,” some more verbiage.

“During audiologic evaluation, speech recognition in noise is often tested in adults and older children with cochlear implants, but it is rarely included in evaluations for young children because of the lack of standardized testing methods.” So now we have the problem. There’s the gap this grant is going to fill.

Then the goal is stated. “The purpose of this study is to develop and determine the effectiveness of –” See, here’s an evil, evil acronym. “– a SR test in noise for young children with cochlear implants.” And this, I could lift that right out of this grant and stick it in my summary statement.

Mario Svirsky:

Sometimes you read grants. And after reading many pages you do not know what the purpose is. That’s bad.

Elena Plante:

Then this grant goes on to give you some information about the nature of the work that’s going to happen. So, “Speech stimuli will be common words and phrases equated for intelligibility.” Some more specifications of the nature of what is going to go on.

Then it wraps it all up with a bow with an importance statement. “Findings may lead to the development of a new clinical speech recognition test for children that can be used to evaluate changes in cochlear implant mapping and benefit of devices to improve speech recognition in noise such as FM systems.” Very little space, hits all the highlights. Tells me why the work is needed, what’s going to happen, and why it’s important.

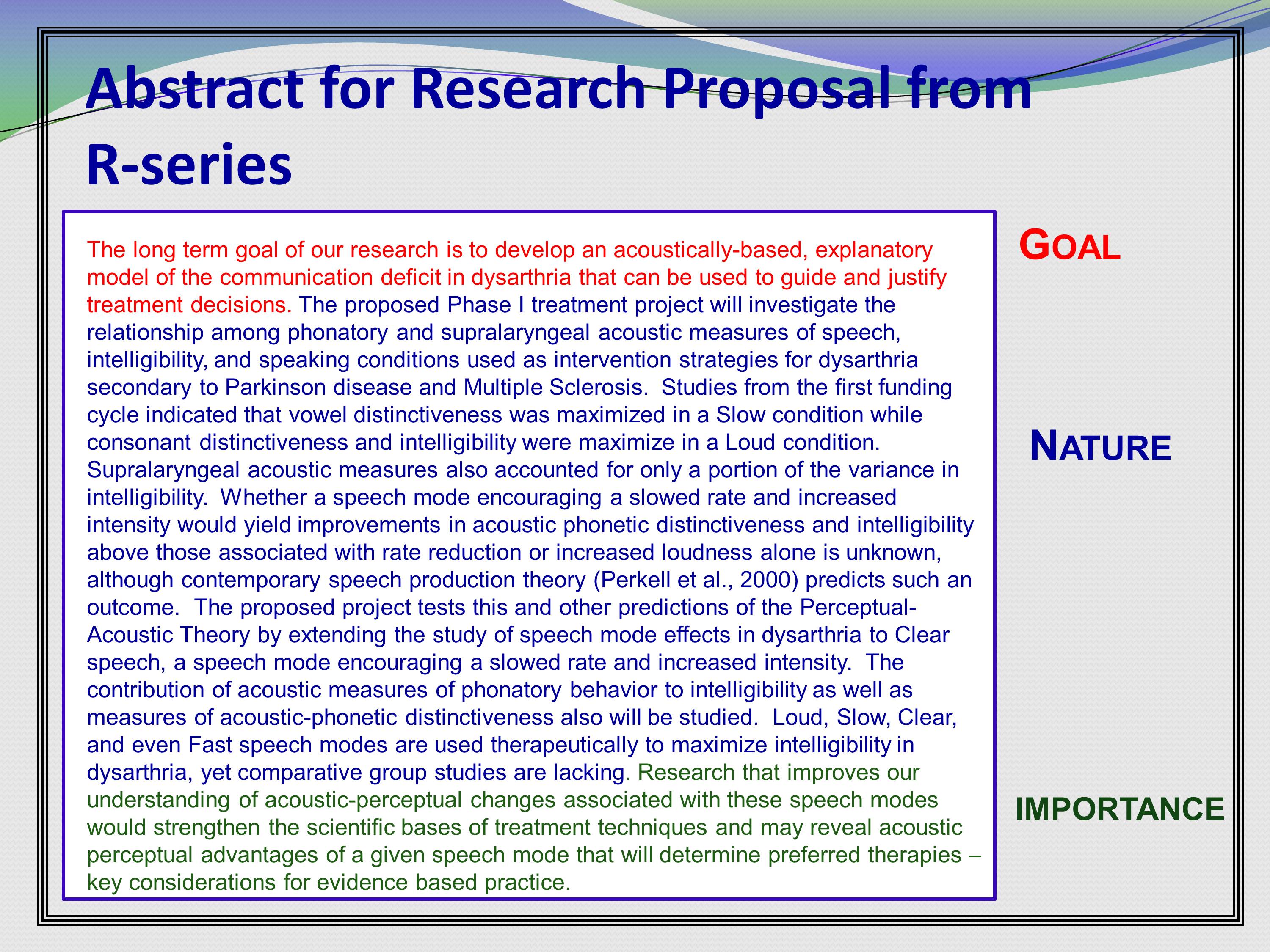

So I’m not going to read this one out, but this is just in a different domain, dysarthria. It tells you the goal right up front. Tells you about the nature of the work. And again, ends with that importance statement. And you can read this as you download the slides.

Biosketch (2010 Version)

CREd Library Note: The NIH biosketch requirements were updated in 2015. Please see Grantsmanship: NIH Biosketch – 2015 Update for more information.

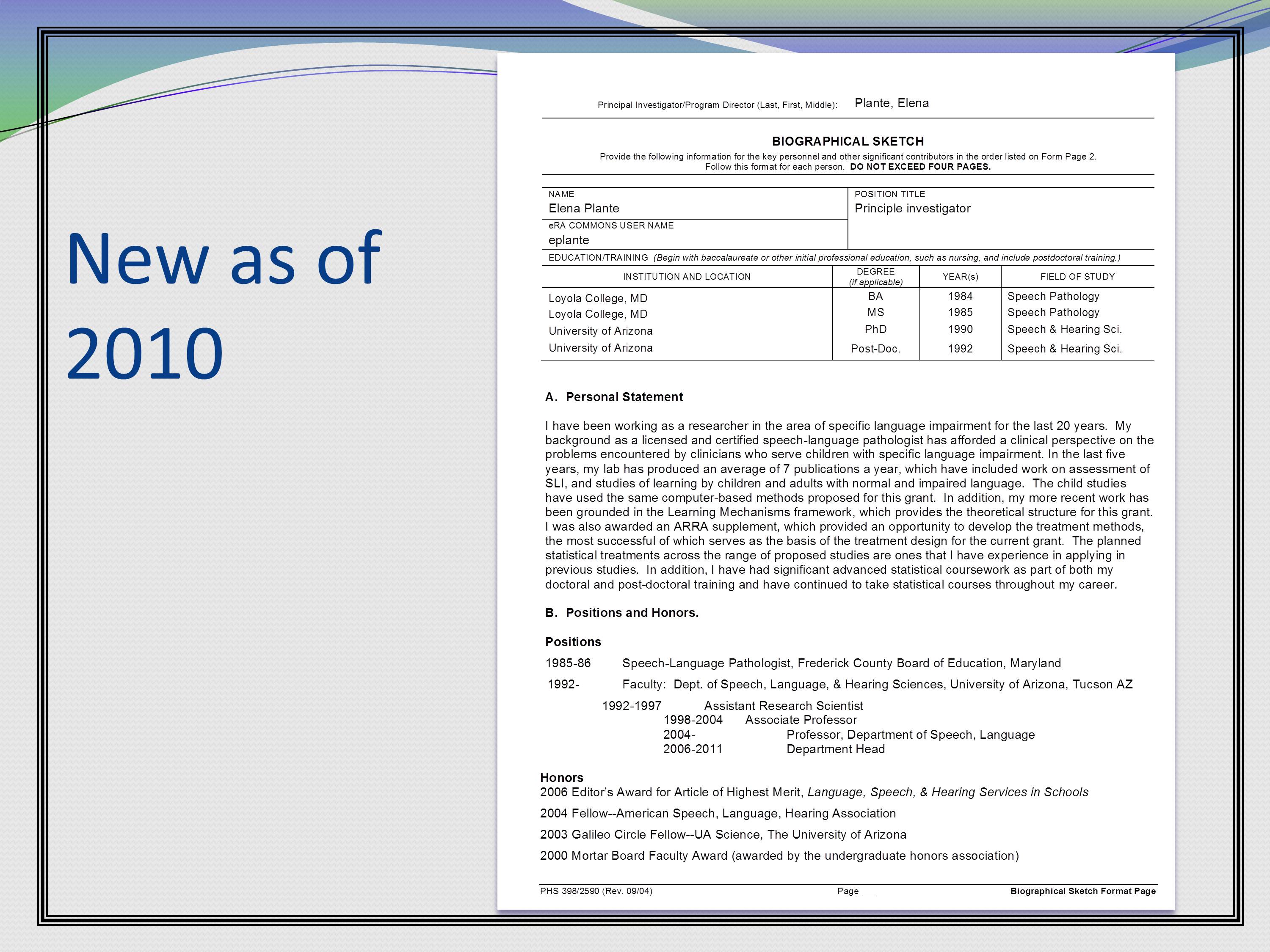

Next section. Biosketch. Again: Follow. The. Directions. This is one of those sections where I see people deviate from the directions most often.

The biosketch functions to convince the reviewer that your key personnel are actually capable of doing the work.

This came up as a challenge. This is one of the places where you can start convincing people that you can do the research, the other key personnel can do the research. You have a track record in the area of the grant. And the people are important for the work being proposed. They’re not just random hangers on-ers or something else. They are actually critical for the work being proposed.

The biosketch contains a personal statement. This is a new component as of 2010. If you get older biosketches you won’t see this. But it’s a paragraph. It’s a paragraph. It’s a paragraph. Not a page, not a page and a half. It’s a paragraph that you use to describe how you are uniquely qualified to do the work. Based on your experience with the method, with the population, with the procedures, things like that. You might also use it to talk about a collaboration that is important to the grant. That you’ve been working with this other person for the last two years, five years, ten years, whatever it is. Keep it brief.

Here’s what I don’t want to hear in your personal statement: How you decided to be a doctoral student and how you ended up at your current institution, and how you’re driven by your love of humanity to do this kind of work. I don’t want to know that. I want to know why is it that you can do the work that you’re proposing. That’s what I want to know.

Mario Svirsky:

And this is not just for you, but of course for all key personnel. What we used to do in the past, we had a collaborator, we asked him for the NIH biosketch. That doesn’t work anymore. Because each biosketch has to be tailored to the specific grant. So writing that paragraph may be something that your collaborator has to do, or it may be something that you do, but it needs some thought in advance.

Elena Plante:

I often write the paragraph for other people’s biosketches. Because I know why I asked them to be on my grant. And then I write it, and then I know it works.

Audience Comment:

I wanted to ask a question about including biosketches, because I’ve heard mixed things. So, collaborators, I know you have to include the biosketches. Do you also have letters of support from them too? Or does the biosketch act as a letter of support saying, “Yes, we’ve agreed to be on this grant”?

Elena Plante:

I would say, certainly, if the grant is paying them the biosketch is fine. If the collaborator is bringing resources above and beyond themselves, then a letter of support documenting those resources might be good.

Mario Svirsky:

A letter of support will never hurt, and it doesn’t count against your page limit.

Elena Plante:

Another thing — I made notes in my last grant review panel about things that annoyed me, and then I put them in these slides — don’t recapitulate other sections of the grant here.

Don’t tell me about the methods. You can tell me why you can do the methods, like, “I have had training in electrophysiology.” That’s good to hear. I don’t want to hear, “I’m going to be using the 10/20 system to map the N400.” No, I’m going to read that in the other sections.

And don’t include information that’s not relevant to the grant at hand. A lot of times I feel like I got the grant biosketch from a different grant.

So, here’s what it looks like. There’s a standard form for NIH. There’s the lead paragraph, that’s the personal statement. Then the instructions will tell you exactly what to put and where to put it.

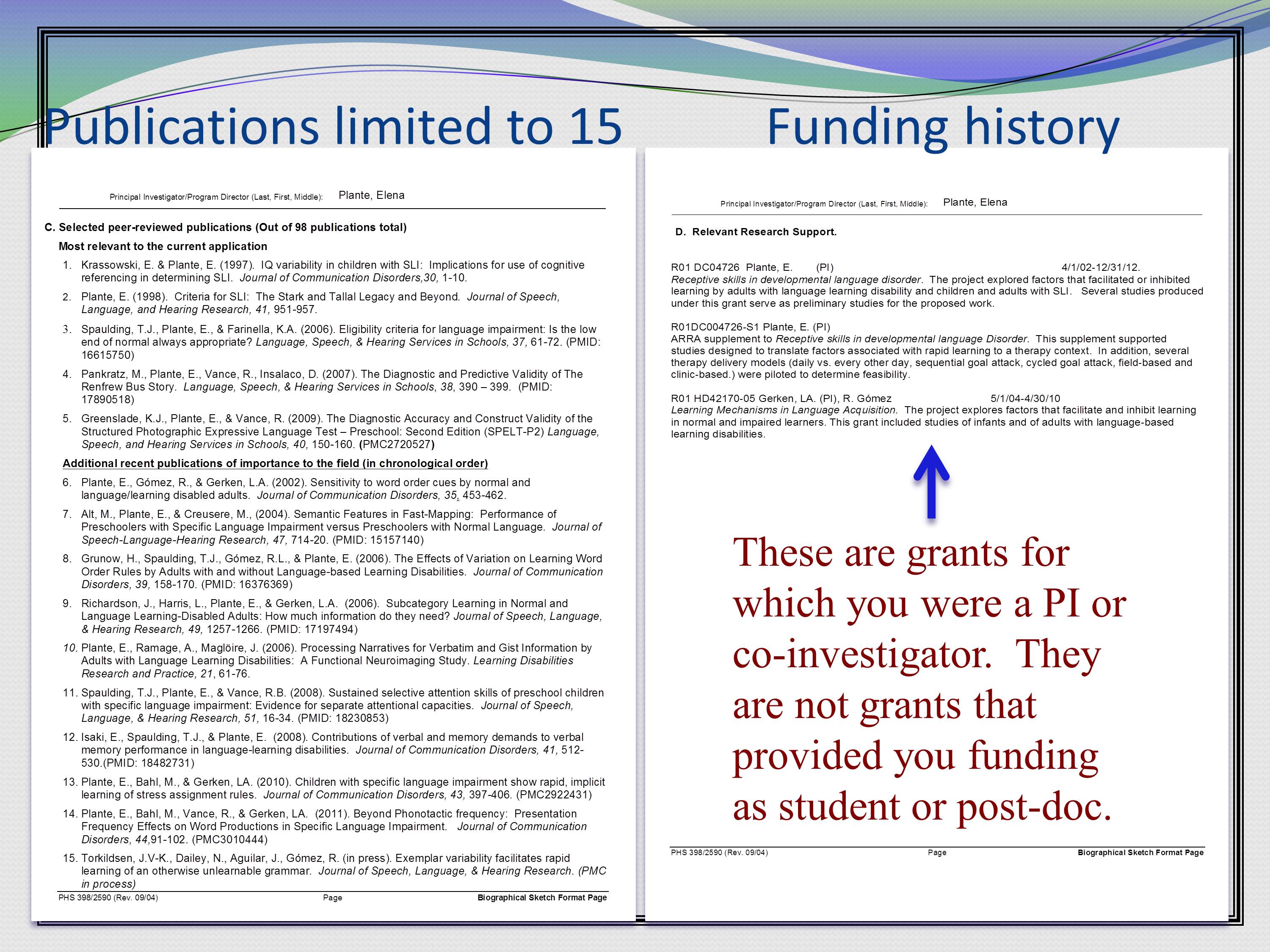

Here’s the next page. So you get 15 publications you can list. You can break them into the things that are most relevant to the grant at hand. And then things that are otherwise relevant for the grant at hand. But you only get 15. If you can’t count to 15, I’m not going to believe that you can do statistics.

And that’s good. Because in the olden days, I got to put all my publications. Which is over 100. And you got to put all your publications. Which I’m guessing if you’re a doc student might be three. Now the playing field is a lot more level.

Then you put other relevant research support. In big red letters here — these are grants in which you were PI or Co-PI. These are not grants that supported you. These are not T32s. These are not grants that you were an RA for. These are grants that you went out and applied for and got. It’s a really naive mistake to put someone else’s grant here.

Audience Comment:

I’ve seen some biosketches where in the personal statement people included work that was relevant to the grant where, this wasn’t in my publication list, but I’m going to be submitting it within the month. Or I do have this abstract that was done. Does that just irritate you because it goes outside the 15? Or is it just pointless?

Elena Plante:

It doesn’t belong there. If it’s relevant to the grant it’s preliminary studies. You put it in another section, and we’ll get to that in a minute.

Mario Svirsky:

Any mention of things like that makes you think of padding, even if it’s not.

Elena Plante:

Again, makes us cranky.

When you are a new investigator, or new to and area, it’s often a really good strategy to add a consultant. If you don’t have a great big track record of publications, then the question comes up, “How do we know you can pull this off?” If you have a more senior consultant everybody goes, “well they’ve got so-and-so on board so that really mitigates their lack of track record in the area.”

But, make sure their biosketch warrants the role. Early on in my career, I was around a lot of big names. And I sometimes discovered their biosketch was not as big as their name. Or they had a big reputation for stuff they did 20 years ago. So this comes down to giving yourself enough time. Because if you find that when the biosketch comes in and it’s not really all you dreamed of, you still have time to go find somebody else.

Back to Mario, don’t pad. Follow the instructions. Leave relevant submitted manuscripts for the preliminary studies section.

However F31s and F32s have different rules for what to include in the biosketch. You’re allowed to put stuff on an F award that you’re not allowed to put on an R or other mechanism. So check the instructions.

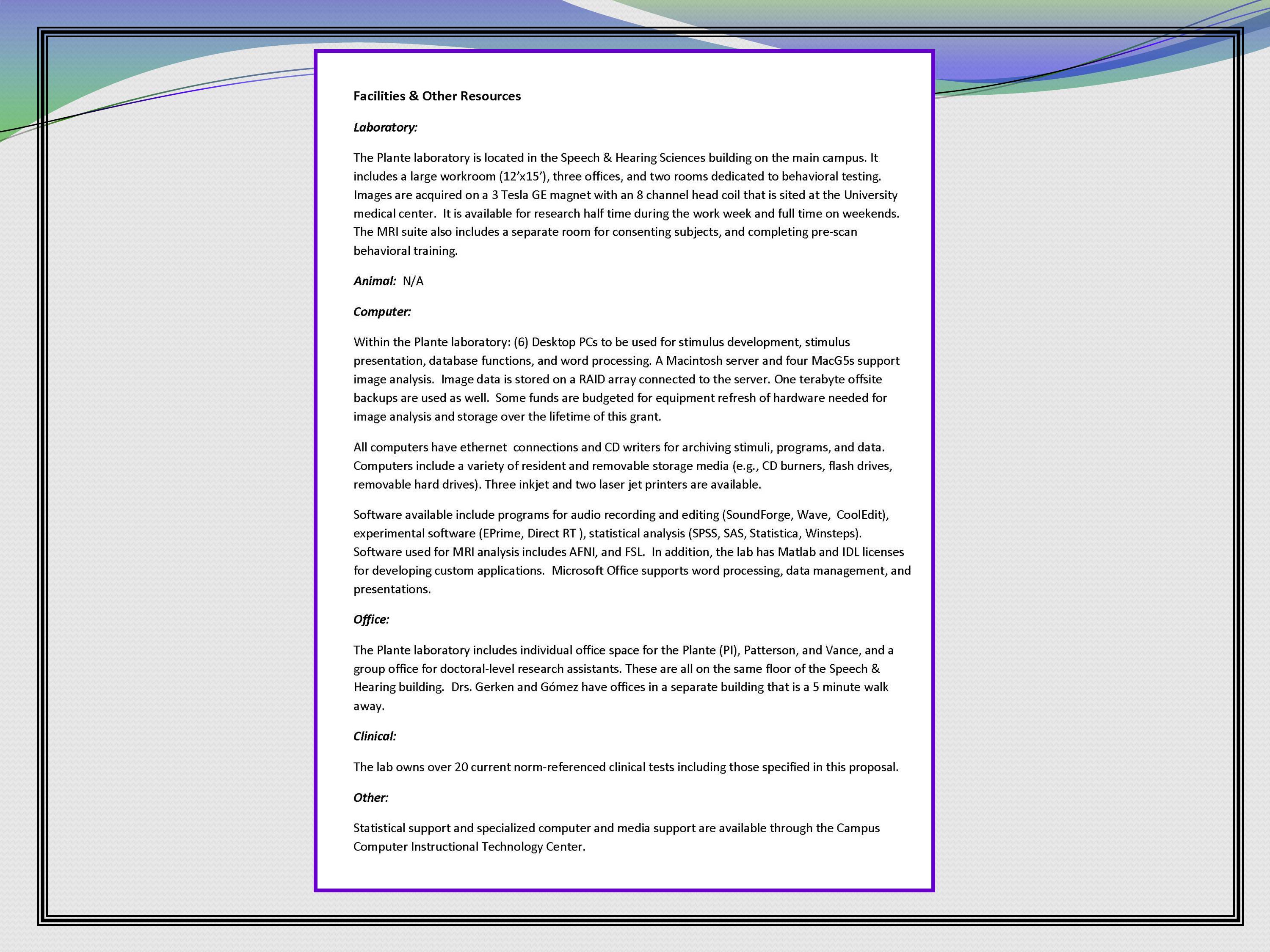

Resources

New section. Resources. The resources section is designed to prove that you have most of the necessary resources to do the work proposed. These things are already available to you. You have the space, you have the major equipment. You have some or all the minor equipment. Also think about the soft resources. For example, core facilities. A lot of universities have core facilities, a lot of examples would be like imaging facilities. Some places have subject recruitment cores, things like that, you can put those in.

Statistical consulting. My university has free statistical consulting. You can be sure I put that in every single grant I write. So those are nice resources.

Leave off resources that are not relevant. This is another section where I get the resources page, and it’s like every single resource this person has available to them, regardless of the grant they wrote this time. If I have to wade through your MRI resources and EEG resources to find out if you have the resources to conduct a treatment study, again, you’re going to make me cranky. So make sure the resources are the ones relevant to the work you’re proposing.

Mario Svirsky:

I would say this section is even more important if you’re not at a top research one university. In most cases, if you are at a good research university, reviewers won’t even go through this. They glance at it, it’s fine, they go on.

Audience Comment:

You see this problem some at institutions with really good grant assistance, where they’re providing a lot of a lot of this administrative information. I guess trying to say you should really have control over it, no matter what kind of institution you have.

Elena Plante:

That’s exactly it. If you’re getting pre-packaged stuff from other people, definitely check it through.

Audience Comment:

Is there a tipping point at which you decide you want to list your statistical consulting under resources, as opposed to having a consultant who is a statistician?

Elena Plante:

I would say it depends on how intrinsic the statistics are to what you’re doing. So, for example, I have a grant funded that does test development. While, the stats are really intrinsic to that. It’s all about the stats. In which case you better have people on board who have the stats chops.

For my other grant that’s funded right now, the stats are fairly routine, so basically I can do them myself. But it’s nice to be able to say, “If I get stuck, I can go to my statistical consultant, who is free.”

Mario Svirsky:

I would say it’s important to have the grant vetted by a statistics consultant, even if it doesn’t have a big role in the grant. Because it’s not infrequent to have a biostatistician in a study section, and they know when they read a grant that was not written by a statistician because you use all the wrong keywords and so forth.

Elena Plante:

I will say, some institutions like IES always have statisticians on the panels. If you know you’re going into IES, you better have your grant reviewed by a statistician. If you’re going into NIH, you’re certainly going to have some people who have statistical sophistication, but they’re not necessarily statisticians.

Mario Svirsky:

You should involve the statistician very early on because ideally they might influence your experimental design. What makes statisticians cranky is when you tell them, “Hey, I have this grant, can you do the stats?” Because that’s not how they like to work.

Elena Plante:

Or, worse, “I have this data, will you do the stats?” That’s way too late.

Audience Comment:

On a similar vein. Is there a tipping point for too many consultants, particularly if they’re unpaid consultants? Or, where do you draw the line on too many consultants?

Elena Plante:

Absolutely, if the number of consultants you have makes it look like you’re going to spend a massive amount of time managing your consultations, that’s too much. Or, if the consultants aren’t directly relevant to the work at hand, or if they’re redundant. That would be bad.

Mario Svirsky:

That’s what matters. You use the consultants that are needed, and you don’t use any that are not.

Audience Comment:

Really quick on the consultants. I’ve noticed that people will sort of name drop on consultants. So they’ll add anybody who was sort of related to what they were doing. It makes me wonder, how well equipped are you to do the research if you really need that many people to guide you, which I look at as a negative.

Elena Plante:

So this is basically what a resources page lays out. You have the title that NIH gives you and a bunch of headers that deal with the different kinds of resources, and you describe what you have.

Again, you don’t need to be flowery here. Just tell us what you have.

Specific Aims

New section. Specific Aims. Along with the abstract, this is the one section that is most likely to be read by most reviewers, even if they do not read the rest of the grant. So we’re going to go through this in a little bit of detail.

The first thing is, aims are not necessarily hypotheses. These are two different things.

Aims are what the grant is going to accomplish. That’s the goal of the grant. Hypotheses are how we think things are going to come out. That’s the big distinction. I know when I wrote my first grant, I really had a lot of trouble with the difference between aims and hypothesis. But I think if you think about it this way, it’s pretty straightforward.

People ask all the time: Can one aim cover multiple studies? Yes. If I have a five-year grant, I often have two or three aims, and I have a lot of studies. Obviously it’s not a one-to-one mapping between your aim and your studies.

This is from a specific aims I wrote. It basically says, this grant has two aims, and you can see after each aim it says, “This will be tested in studies 1-4.” And then aim 2 is tested in studies 1, 3, and 5.

The other thing to notice is that we have some studies that are testing both aims. That’s okay, too. Because the aim is what your grant is going to accomplish.

Reviewers will hold you to your aims. So show how the background and the significance and the innovation relate to the aims. Link each study to an aim. Bold these points in the text so we can find them and we can see these links ourselves. So help us there.

I can tell you, if your aims do not match the other sections of the grant, there is no way you are getting funded. No way. Because the response that will come back is they have this set of aims, and they have methods that will not answer that aim.

It doesn’t matter that if there was a better way to answer that aim that your study actually does map onto, we’re still not going to credit you for that.

Mario Svirsky:

Aims also need to be specific. If you have an aim like, “I’m going to understand cognitive processes in hearing loss.” That is not a specific aim.

Elena Plante:

“To explore” or “to investigate” is too broad and is not a specific aim.

This is an example of some of that linkage. Here’s a study, there’s little preamble to that study, two sentences, and then it says, “This is relevant to Specific Aim 2.” So this grant is explicitly making the link between the study at hand and the overall aim. So that at 11:00 at night, I can make my match myself.

Finally, aims should be short and skimmable. Because, again, at the table people are reading through that for the very first time. So make it short and skimmable.

The Aim typically has several components. First, it has a lead-in that orients the reader to the problem to be addressed, the theory or model the work relates to, the general methods, and the importance.

Then there’s the actual aims and usually some general hypotheses. The reality is, your individual studies probably have a number of very specific hypotheses. We don’t want to hear about those in the aims. Just tell us the general hypotheses.

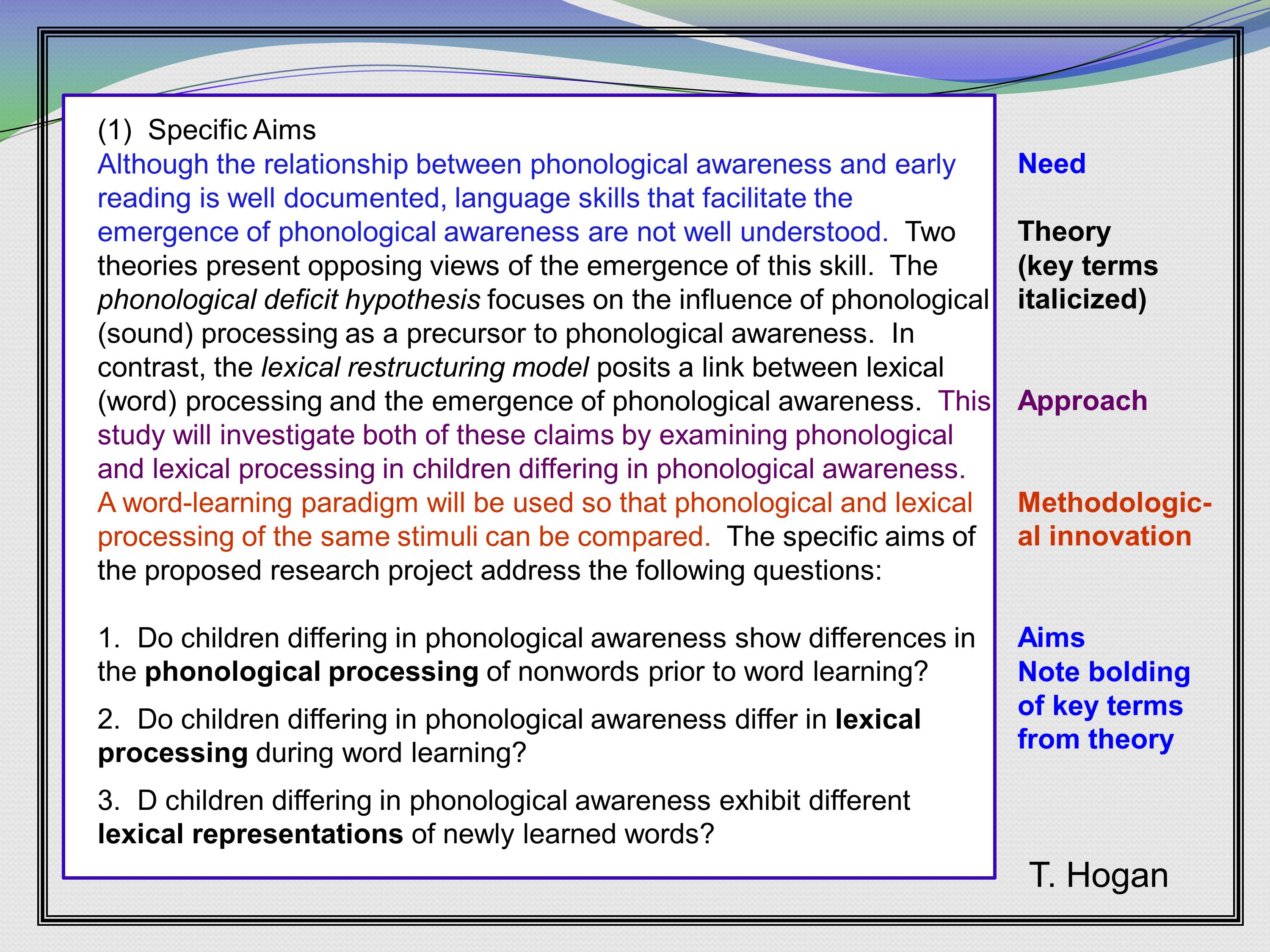

Here’s a really nice example. It came from an F31. It’s one of my favorites, ever, because this aim accomplishes a lot in a very little amount of space.

In the very first sentence this writer establishes what the need is that this grant is going to address. “Although the relationship between phonological awareness and early reading is well documented, language skills that facilitate the emergence of phonological awareness are not well understood.” That’s the problem space.

Then, next part. She gives us two competing theories. “Two theories represent opposing views of the emergence of this skill. The phonological deficit hypothesis focuses on the influence of phonological (sound) processing” — so see, she’s helping people who are not quite in her area by saying this is about sounds — “sound processing as a precursor to phonological awareness. In contract, the lexical restructuring model posits a link between lexical (word) processing and the emergence of phonological awareness.” So now she’s set up two competing possibilities that need to be resolved.

Then she tells us about how she’s going to attack this problem. “This study will investigate both of these claims by examining phonological and lexical processing in children differing in phonological awareness.”

Then she tells us why her methods are innovative. Remember innovation is one of those score points that we look for. “A word-learning paradigm will be used so that the phonological and lexical processing of the same stimuli can be compared.”

And then she gives us the actual aims. And here, what she does, is she bolds the points here that relate back to the theory. So here’s the phonological processing, the lexical processing, and then lexical representation. Coming back to these concepts that appeared above. These are nice, beautifully laid out aims.

Mario Svirsky:

There is nice spacing between the aims, too. Remember that I had to review 12 grants, I’m cranky. And I read the whole grant a month ago.

Elena Plante:

Or maybe I didn’t read this one.

Mario Svirsky:

Trying to remember what it was about, I can go to the Specific Aims. I see that they’re here. And I see the bold words “phonological processing,” “lexical processing,” and “lexical representations” and I remember.

Elena Plante:

It’s a thing of beauty.

Some common mistakes. First of all, the aims are a wall of words. My least favorite thing to see. Because I’m starting my actual review here. I’ve skimmed through your abstract, but I don’t score the abstract. I’m starting my actual review here, and the first thing I face is this wall of words, and my first thought is, “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

The second most common problem is the aims are too long. The third most common problem is your aims are too long — really. They really are.

The aims don’t tie together theory with importance, with the goals of the grant.

The aims and hypotheses are confused.

Or the aims are not formatted for skimmability.

Those are the most common problems I see.

Research Strategy: Significance/Innovation

On to the next section. This is the whirlwind introduction to grantsmanship. Research strategy is the biggest section of an NIH grant. The components are the significance, the innovation, and the approach.

Significance and innovation is where you sell us on the grant. It couches the work in a broad theoretical framework or model. This is an opportunity for a figure.

In my experience, there are visual people and there are not-visual people. The not-visual people don’t like to use figure. Well, that’s fine. Unless you have a person who is a visual person reviewing you. In which case, they are cranky. Because they cannot skim your grant and figure out what you are doing.

If you are not good at doing figures, get someone to help you. Because if you are a visual person and there aren’t any visuals, that’s no good.

If you’re a word person and you get a visual, you don’t care and you skip right over it.

So here’s an example about introducing theory. You don’t have to make a huge deal about it.

So, in child language there are these two camps. And if you want to see an interesting screaming match, get these two camps in the room. And these are two camps: One basically says that language is innate, you just need some input, it’ll all get triggered, you’ll all be good. The other says that nope, you actually learn it — so these could be considered non-triggering accounts.

This one little paragraph just basically sets up, well you’ve got these two camps, and we’ve got to resolve between them. So in one paragraph, she’s introduced two theories.

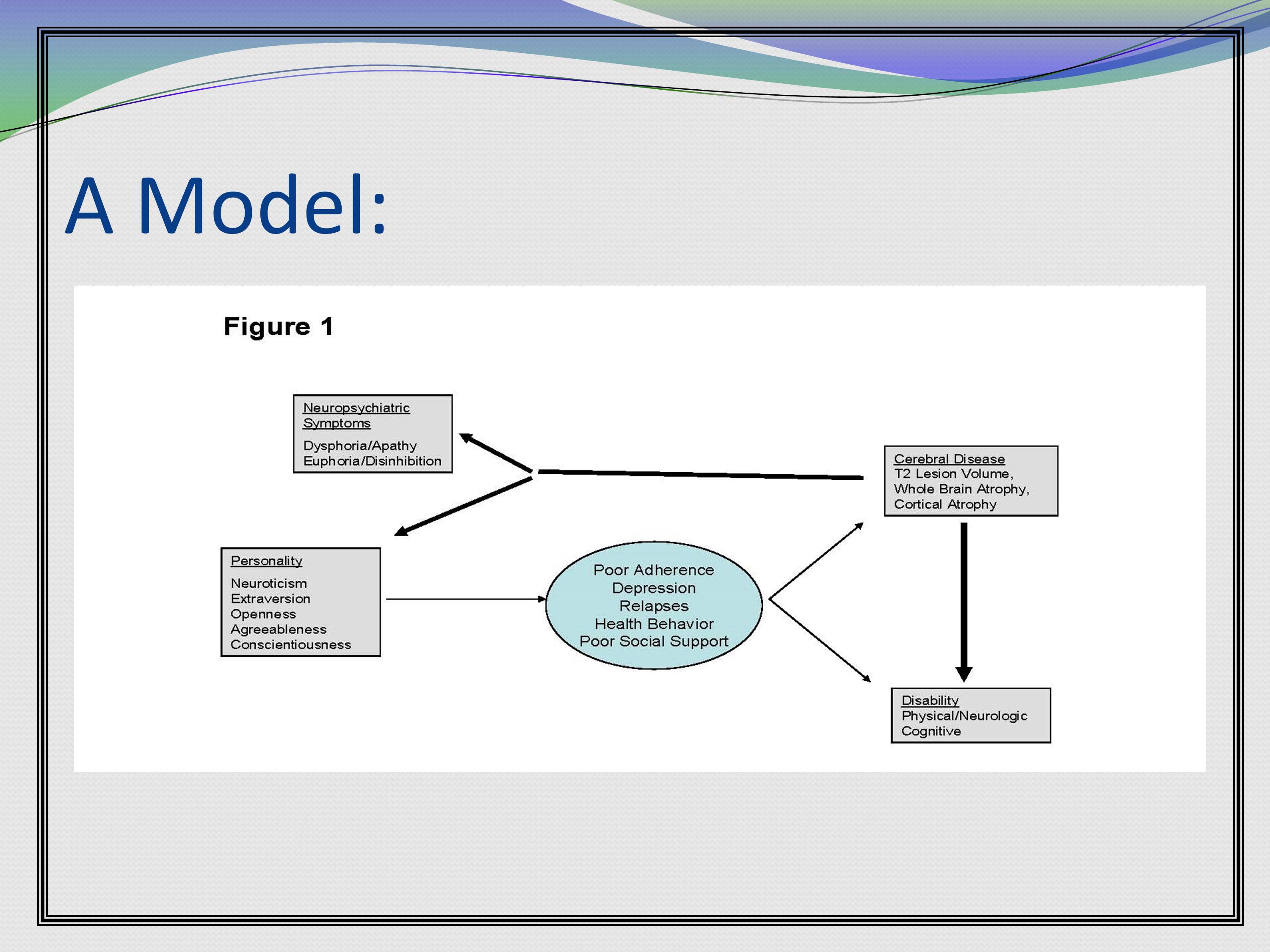

Here’s a figure example. This basically lays out all the major concepts of this grant, and how they’re expected to interact. Then the rest of the grant is going to refer back to this central figure.

It is critical that you emphasize why this work is important. Because the score that gets you to the table is whether you’re going to make a sustained and powerful impact on your field.

You should identify where the critical gaps in your literature are, show why the work is interesting, show why the findings will be important, and give a sense of why the work is needed now.

That was Ed Conture’s major point: You have to come away with this sense that, of course this work has to be done. The field cannot move forward unless we have this now. That’s the sense you want to convey.

Mario Svirsky:

The significance section is supposed to answer the question: “Why should we care?”

So, going back to when we suggested that you should give your specific aims to colleagues and so on. If your colleague says, “Oh, this is very nice, that’s good.” That’s not the reaction you are looking for.

The reaction should be, “Oh, that’s really cool!” You can tell he’s thinking, “I didn’t know you still had it.” You want people to get excited about something. Excitement is what significance is about.

Elena Plante:

The last grant I reviewed from a colleague, the reaction I had was, “This is so clever. This is so important. I can’t wait for you to know the answer to this.” That’s the reaction you want to generate.

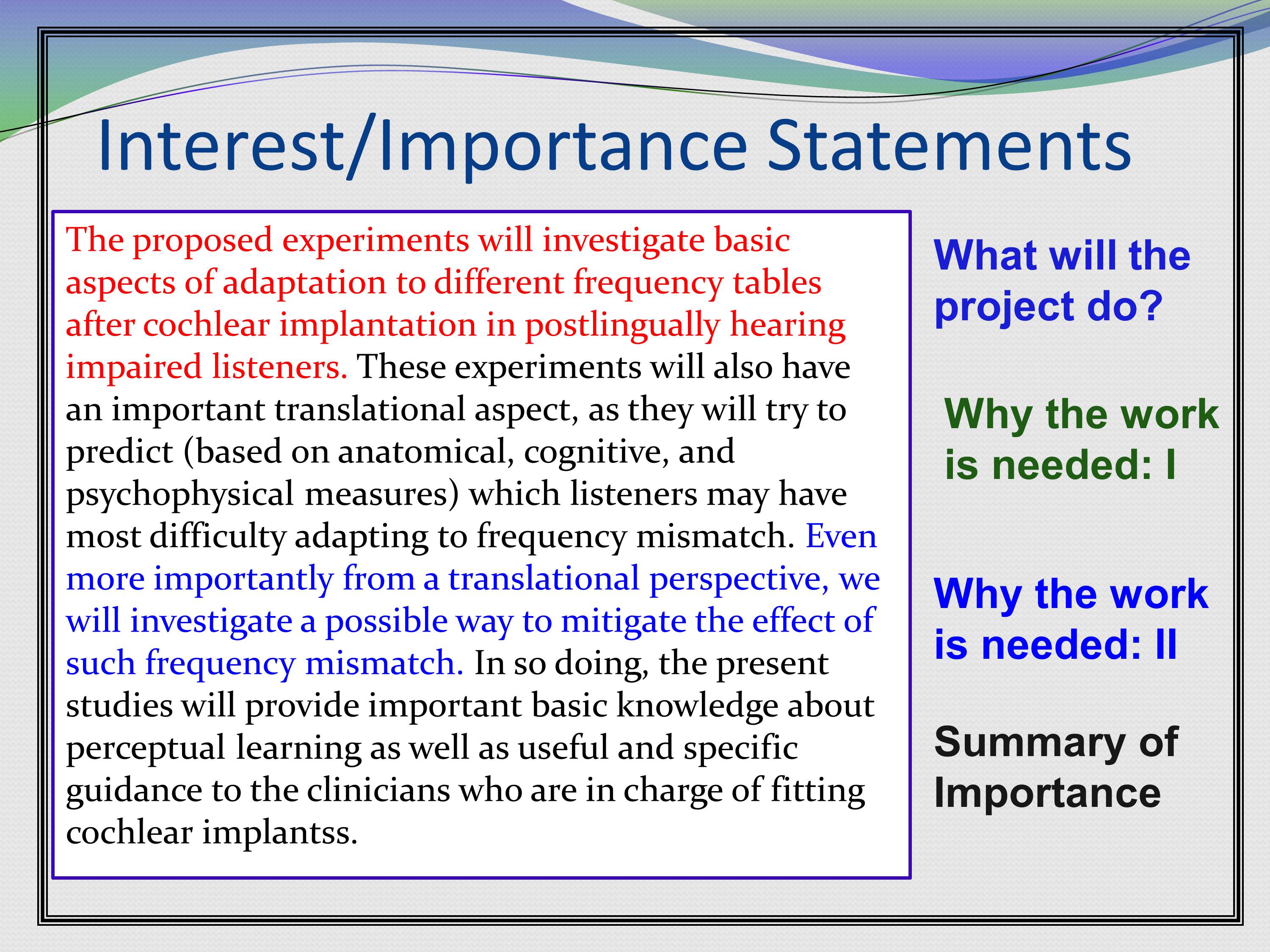

Here’s some examples of interest and importance statements that were in a grant. Basically the first line of this paragraph is what this project is going to do. It’s going to investigate basic aspects of adaptation to different frequency tables after cochlear implantation in postlingually hearing impaired listeners.

Then the next sentence is why the work is needed. Because it will have important translational aspects, as they will try to predict (based on anatomical, cognitive, and psychophysical measures) which listeners may have most difficulty adapting to frequency mismatch.

Then, if that wasn’t enough, they give us another reason why it is needed. Why it’s needed II, or return of the need. Even more importantly from a translational perspective, we will investigate a possible way to mitigate the effect of such frequency mismatch.

Then, a summary of the importance of the whole thing.

Mario Svirsky:

And that example is specific. One of my pet peeves when reviewing grants is that a lot of them will say, “This grant will provide useful knowledge to improve the next generation of hearing aids and cochlear implants.” Sometimes it’s obvious that that may be the case. Other times it’s total BS because there’s no possible relation between one and the other. So, if you can make a case that’s specific, that’s good.

Elena Plante:

If you want to make my eyes roll, write the sentence, “…and this will guide future treatment directions.” My reaction is, “Okay, I’m a clinician. Prove it. Because I’m not seeing it.”

Finally, the significance and innovation is not an exhaustive review of the literature. It is tightly written to the aims and studies, rather than being exhaustive.

Just set up what you’re going to do, and motivate it and tell us why it’s important.

Now, I’ve been saying “significance/innovation” because when I write these two sections, I actually write them as a whole.

You might want to know how you divide these up. Basically what I don’t like to see an innovation section say is, “This work is innovative because this, and this, and this.” I see that a lot. And I think it’s because people haven’t really worked through this new format.

I want to see the innovation idea developed a little bit. What I do is I think about what part of my background really motivates the need for this work. I put that in the significance.

Then I think about what part of this work is new, novel, and pushes the boundaries of the research. I put all of that in innovation, and I flesh it out.

So I have two really nice sections of approximately equal length. I don’t give a bullet point list of, it’s innovative because of this, and because of this, and because of this. The risk you run is that if I say, “I don’t believe it.” Now you’re stuck. You’ve got no innovation section.

This section should be tightly written to the studies. What you want to do is develop a laser-sharp focus on your problem. You want the problem to be solved up front. You don’t want to do an exhaustive literature review — provide key references when necessary.

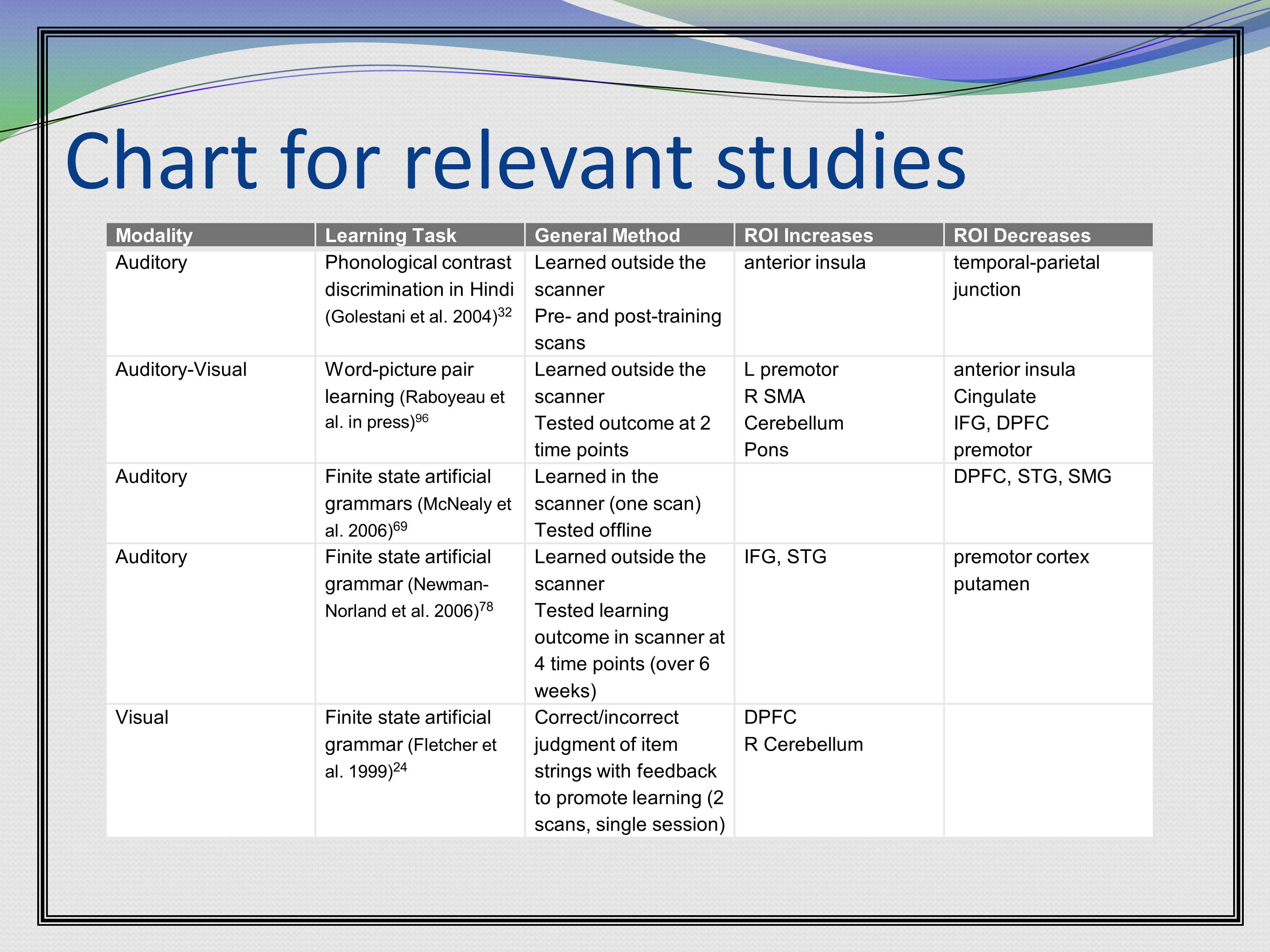

Consider figures that capture the essence of the issue being addressed because that will provide an organizing framework for the reader. And consider charts for summarizing where we are as a field.

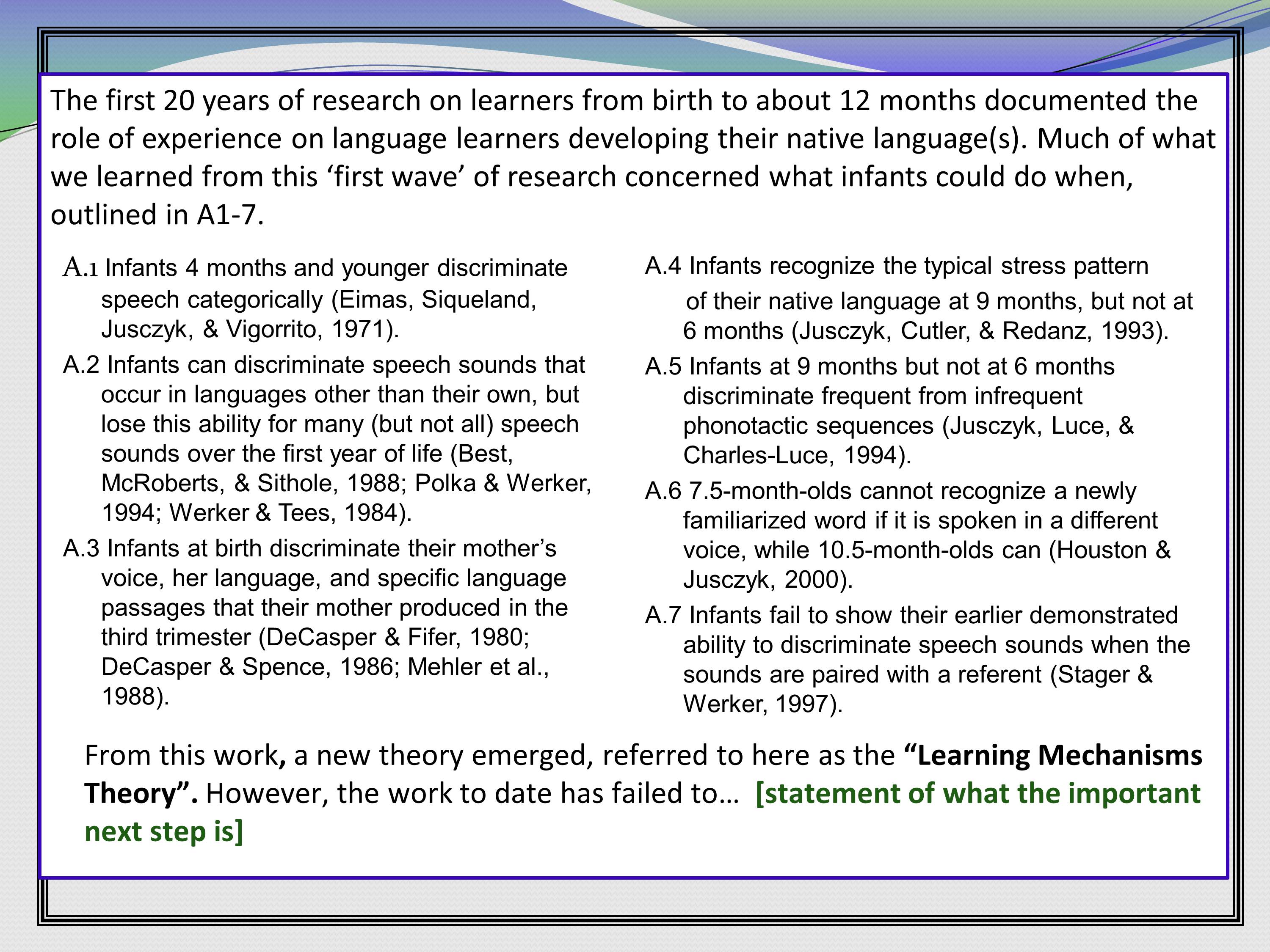

I’ll give you some examples. So most of my really great grantsmanship tips I stole from other grants. Here’s one I stole. I was technically on this grant.

This writer, LouAnn Gerken, summarizes 20 years of research in this amount of space. She basically says, for the first 20 years of research on infant learner, from birth to 12 months, here are the major principles that came out of that. And she just tells us what they are.

Then she ends with, “from this work, a new theory emerged, referred to here as ‘the Learning Mechanisms Theory’. However” — and here’s where she’s going to tell us where the gap is — “however the work to date has failed to…” And then she going on to say what the important next step is.

That’s a lot of years of research summarized in a very small amount of space.

Here’s another example from one of my grants. A grant that’s funded now. Basically, at the time I wrote this, I do imaging research of learning, and there weren’t that many studies that looked at learning as people were in the scanner. But there were few key studies. So I put them in a table, and I put the relevant specs for each study in the table. So in the text I could just refer them back to the particular study I was talking about without having to give all the specifics in the massive amount of text. This makes it very easy for the reader to refer back and answer very specific questions they might have about a particular study.

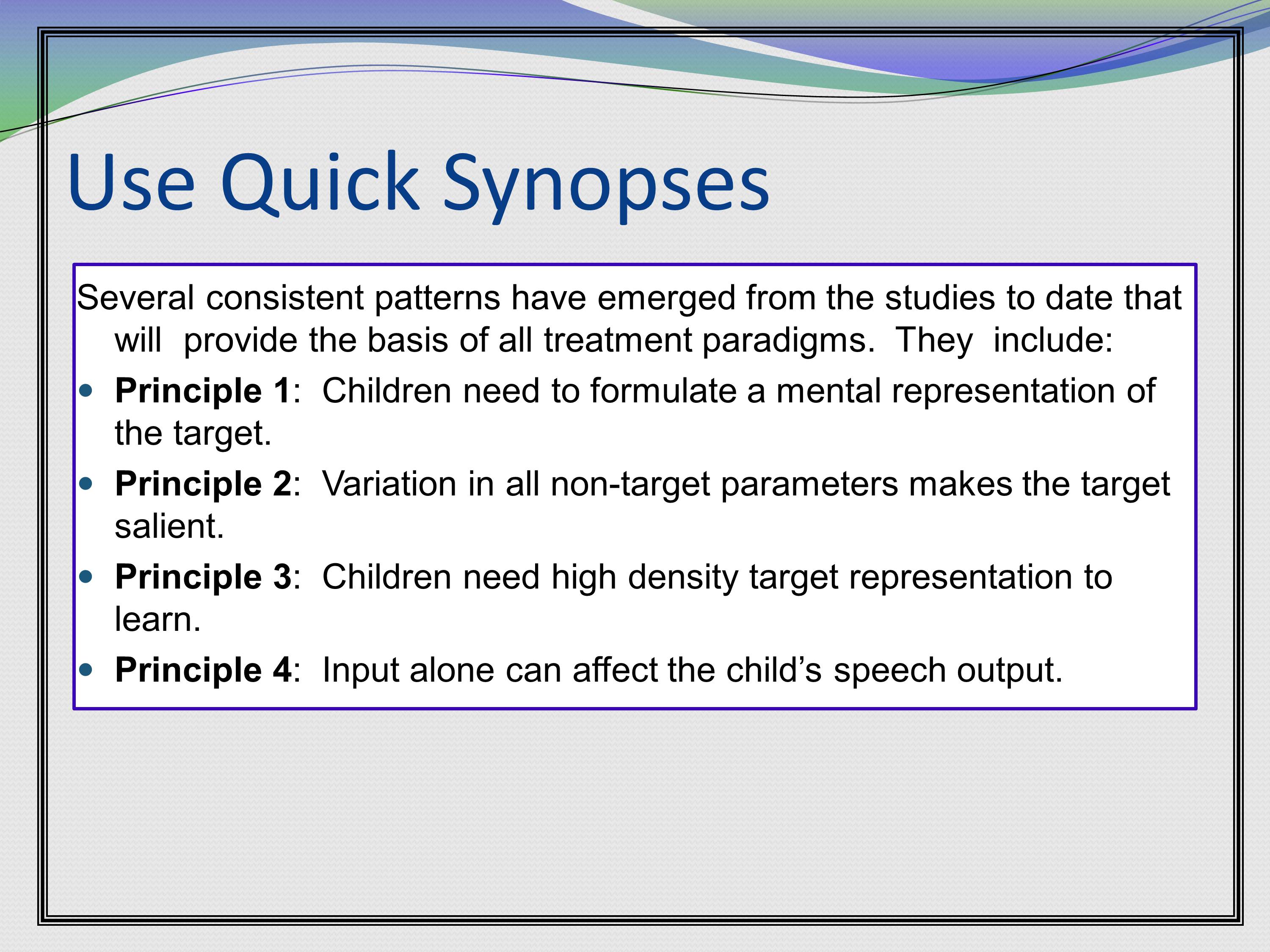

Another example is to summarize with principles that will inform the approach that you’re going to go forward with. In this — this is a treatment study of mine — where we say, “Several consistent patterns have emerged from the studies to date that will provide the basis of all treatment paradigms. They include: Principle 1 blah, blah, blah. Principle 2 blah, blah, blah.” I’m telling them exactly what we’ve learned that’s going to guide the work going forward.

Research Strategy: Approach

Next subsection: the Approach. This is where you’re going to tell people your methods. This is not the place to gloss over details. You have to tell people enough that they know you can do the work well.

If it is innovative, you need to show that it’s innovative and justify why that innovation is going to be better than what has been done before. Justify your methodological decisions from the literature. Even when you don’t think you need to.

One of the things that drives me absolutely nuts is when people from my area throw down a bunch of subject identification criteria, and I actually know of literature that opposes that. That’s going to kill you. Reference why you’re picking out this test. Don’t just tell me it has good psychometrics. Because I know a lot about psychometrics, and I can tell you not all psychometrics are created equally.

Write to counter possible objections or mistaken assumptions. So, I’m in the non-triggering camp of the two camps that argue with each other vociferously. I know the other camp is out there. They may be reviewing me, so I’m going to write my methods to counter those objections that might come up — or, as I like to think of it, their mistaken assumptions.

Mario Svirsky:

I think it’s a good idea to remind people about innovation. But if there’s any content about innovation in your approach section, make damn sure it’s also present in your innovation section. Otherwise it may not count.

Elena Plante:

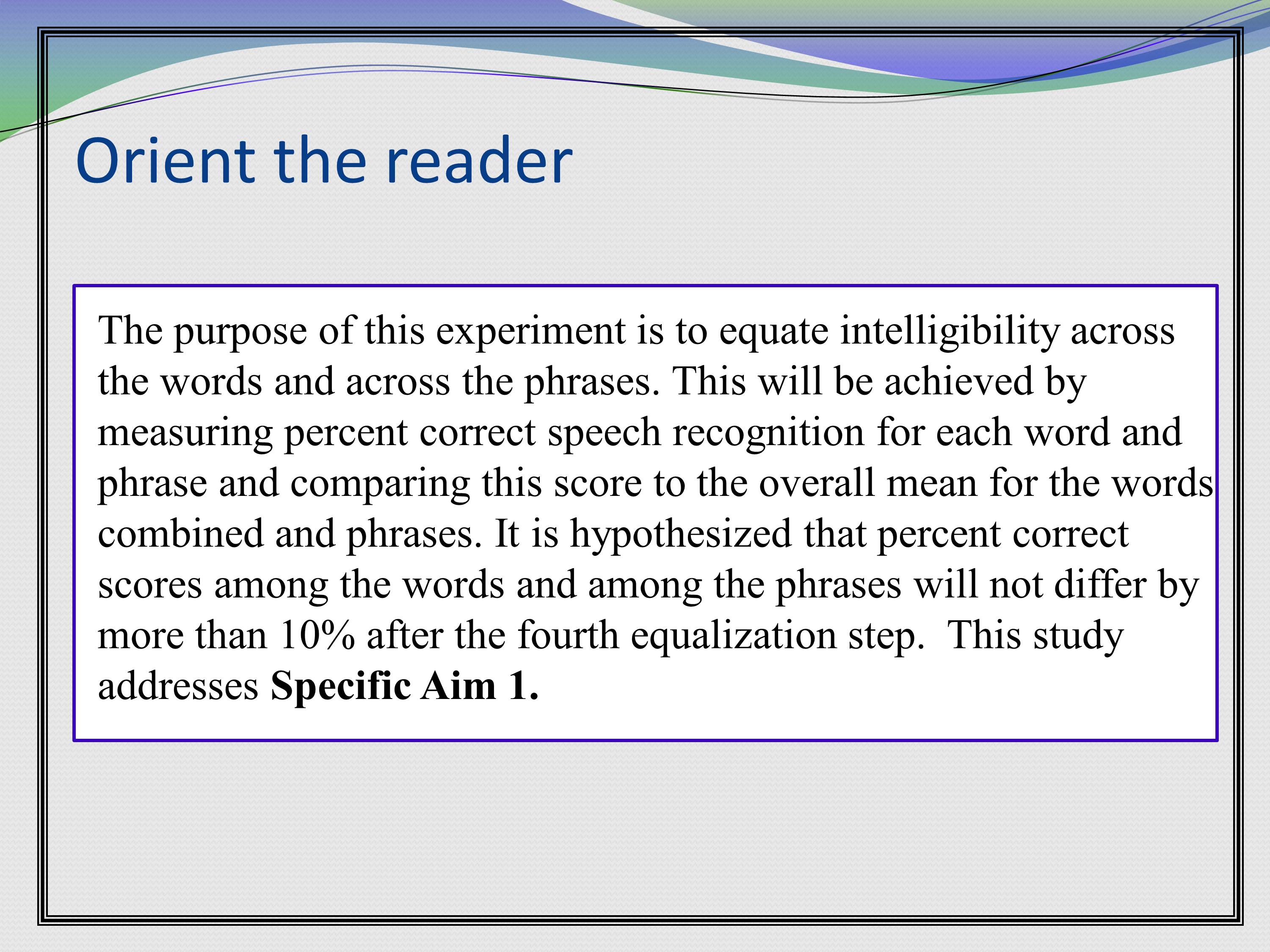

As I said, it’s sometimes a nice idea for each study to have a little orientation to get your readers’ head around the purpose of the study and, again, to link it to the aim it refers to.

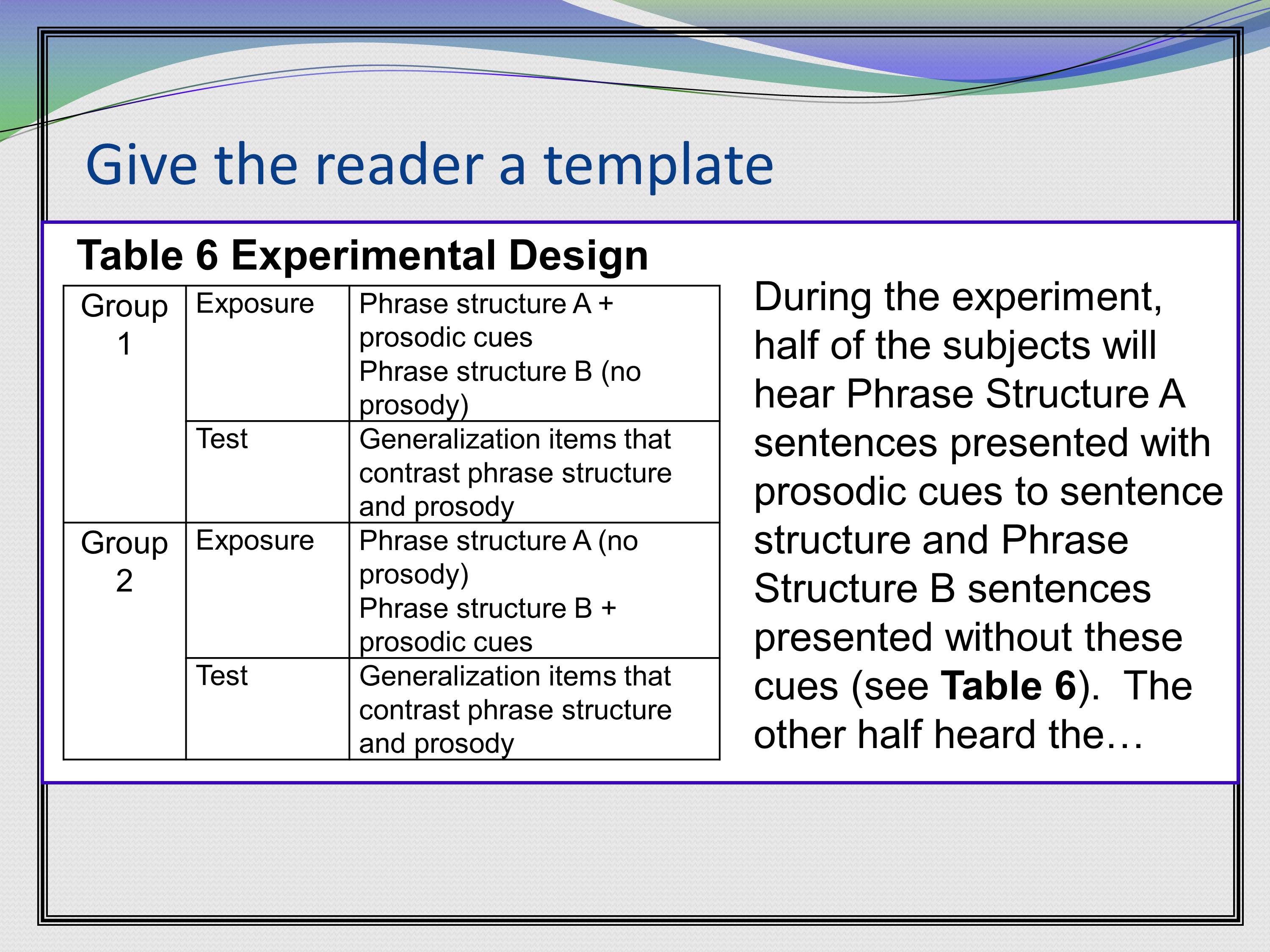

Another good tip is to give the readers a template for your study. Particularly if you’ve got a lot of complex manipulations. Go ahead and table it.

Here’s a study where we’ve got two groups, they’ve got two phases of each study. We have group 1 and group 2. They both get an exposure phase and a test phase. Then it lays out what’s different about these for the two groups. The text is continuing on, on the same page. But we’ve bolded here “Table 6.” So if someone is skimming through your grant and is looking for more information, they can find it in the text quickly.

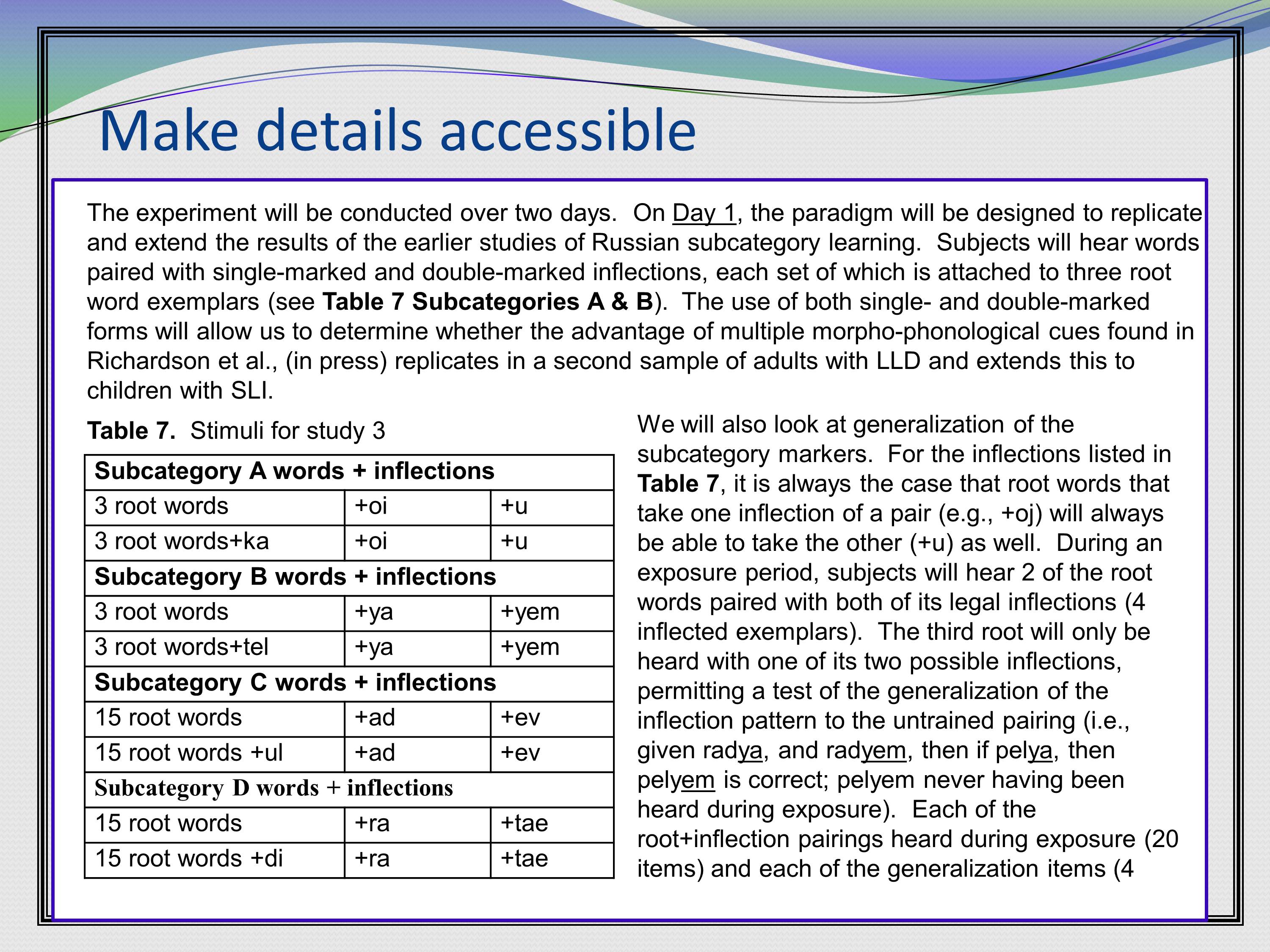

Here’s another example of making the details accessible. This one is about the types of stimuli to be used, where everything is all laid out in a very skimmable fashion. Again the “Table” is bolded in the text so you can find it if you are skimming.

Some space savers. Because we are all looking for ways to save space. Summarize common elements separate from specific studies. So, if you have five studies that all deal with SLI, tell me once about your SLI subjects. Or if you have the same selection criteria for 7 out of 10 of your studies, tell me studies 1 through 7 are going to use these subjects, subjects 8 through 10 are going to use these kinds of subjects.

Same thing with the data acquisition. If you’re doing similar data acquisition across studies just tell me once and other kinds of things like that. Usually you should have one statistical section, not a separate one for each study, if you can get away with it.

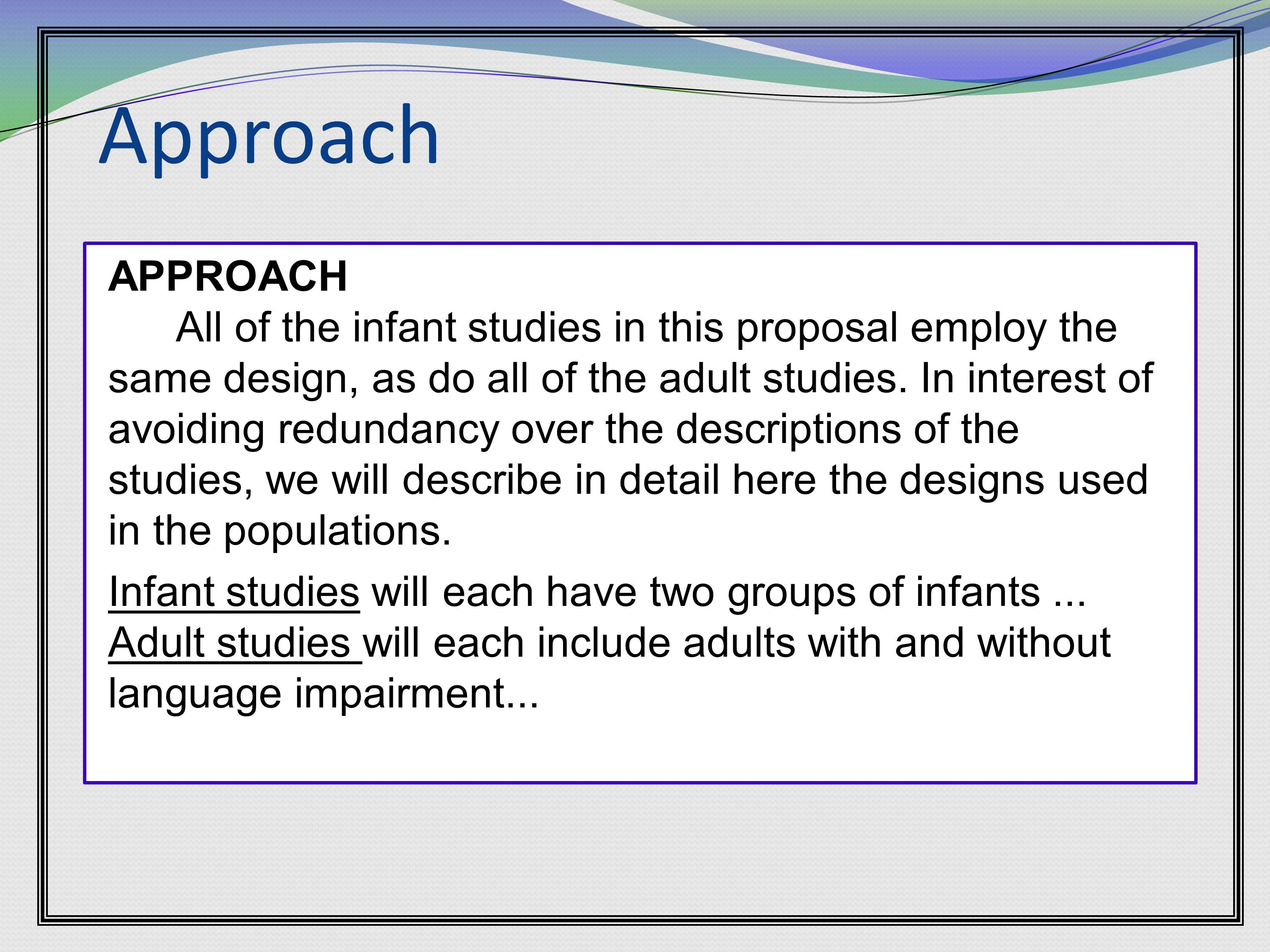

Here’s an example about summarizing all the similar subject selection. It basically gives a lead in that will orient people to the fact that there are going to be infant studies there are going to be adult studies. And then there are subsections for each of those types of populations.

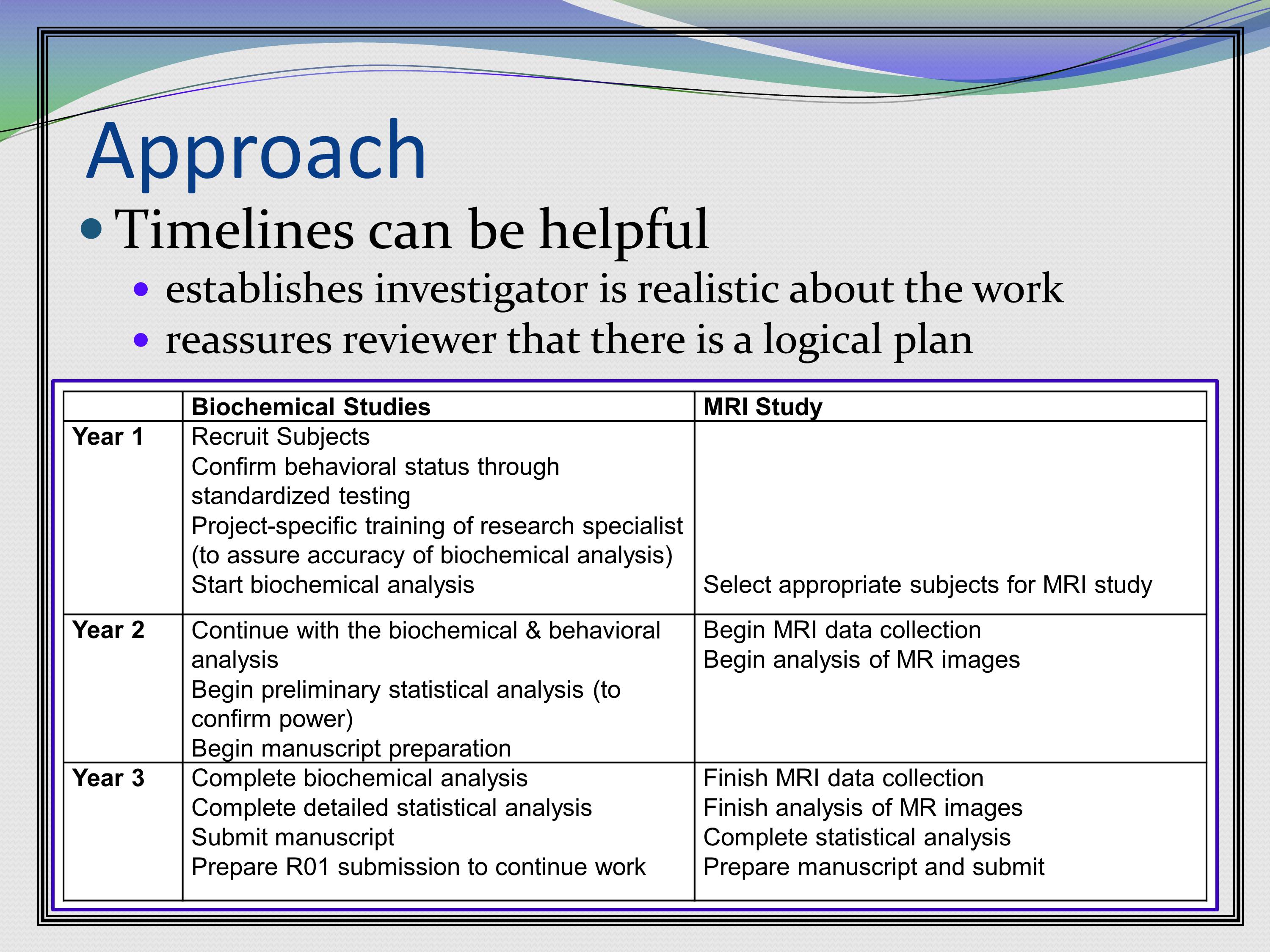

Timelines can be really helpful. Particularly for junior investigators because it answers the question “Are they naive about how much work is going to go into this?”

If you give us a timeline — and it doesn’t have to be too detailed — just kind of tell us what the major events are, it does go a long way to satisfy that.

Here’s a grant that had two different kinds of studies, MRI studies and biochemical studies, and what was going to happen in each year. I didn’t break it down by month, just Year 1 we’re going to do this, Year 2 we do that, for this kind of study, for that kind of study.

Here’s another example of a timeline that’s laid out in a different way.

Ogden & Golberg have a great book about grantwriting. Ogden used to be a program officer at NIH. It’s a little outdated right now, so you have to get another resource. They still have background and significance, which is the old way. Now it’s significance, innovation, and approach. So you do have to kind of do this mental translation. But the advice transcends the format, so I still recommend it to people.

So first recommendation: Do not assume reviewers are familiar with your methods. Because, as I said, I’m reviewing all kinds of things. I review MEG grants. I do actually have experience with MEG back in the days when they had single-dewar systems. In the 1980s. So you’re going to have to hold my hand a little bit.

Use tabular data to summarize the design. Use flow charts to summarize procedures.

Anticipate problems and present potential alternatives. If you anticipate a problem, and present an alternative — some people use a section for this “Potential Problems and Possible Alternatives,” I love to see those sections. Because it makes you look sophisticated about your grant. If I think up a potential problem that you didn’t think up and give me an alternative for, now it’s a weakness.

Here’s an example of that section. This says potential problem number one is “the adaptive speech recognition in noise test may be difficult for the younger children in terms of the task and attention.” But there’s a solution. “Children will be given frequent breaks and snacks between conditions to help with attention and focus. If necessary, the children may need to be scheduled for two testing sessions.”

I’m thinking, “Oh, this person has actually worked with children.”

Then there’s a second potential problem. “If children are only able to complete one or some of the conditions in the study, their data will be included in the analysis.” The solution: “If children cannot participate in any conditions because of inattention or frustration, they will be dismissed from participating in the study with no consequence.”

At least I’ve thought about the fact that this might happen with three-year-olds. And again, I was like, “Okay, this person actually has worked with kids. Because they’re like that.”

For statistics, you want to provide a power analysis for each study. That’s required. Don’t skip it.

Link the analyses to the hypotheses. So make sure there’s a clear mapping between what you’re hypothesizing and how you’re going to analyze it.

Then again, this is a place where we really want to see alternatives. For example, what are you going to do if your data doesn’t meet parametric statistical assumptions? What are you going to do if you have a treatment study, and you’re measuring outcome in terms of percent correct at the end of treatment, and everybody ceilings out. What are you going to do then? Do you have an alternate way of determining which was the best treatment? Think about these things.

Preliminary Studies

Preliminary studies. Again, the old grants did this differently. The new grants you have a lot more flexibility. It can be its own section. It can be integrated with other sections. If it’s in its own section you can put it anywhere you want in your grant.

So, you basically can do whatever you want that makes the best case for your grant.

The preliminary studies section answers the following: How do the reviewers know that you can do the proposed work? And how do the reviewers know that the proposed methods are likely to be successful? That’s what your preliminary studies are addressing.

Some of your grants that you’re writing, like the Fs and the R03 and the R21s say that preliminary studies are not required.

And then you’ve got the reviews back that say, “Well, there’s no pilot data or feasibility data.” And you’re thinking, “But there’s none required.”

Well, let me tell you. There’s a difference between “preliminary studies” and “pilot and feasibility data.”

Preliminary studies are directly relevant to the proposed studies. They are usually things that are published already, or in press, or done. They’re done. And they were full-up studies.

Somebody said, “Well, I really only have pilot data.” But it came out in JSLHR. She says, “It only has four subjects.” But, if it’s published it’s not pilot data. It’s a preliminary study.

Pilot data are typically data you collected for the grant at hand. They should be clean, robust, and convincing. Your hypothesis should be in the direction your pilot data is going in. I’ve seen the other happen.

Tables, graphs and images are appreciated. And again, it can come anywhere in the grant.

Mario Svirsky:

It’s rare to have too much pilot data. But I’ve seen it happen where somebody says, “Well, this is the first 15 subjects of an experiment that’s going to take 20 subjects total.” So they actually did the first experiment already. But that’s extremely rare.

Elena Plante:

It used to happen a lot more often, but I think people got beat down enough about it. Because if we think, “If you managed to do 15 subjects without my resources, why do you need resources to do the last five.”

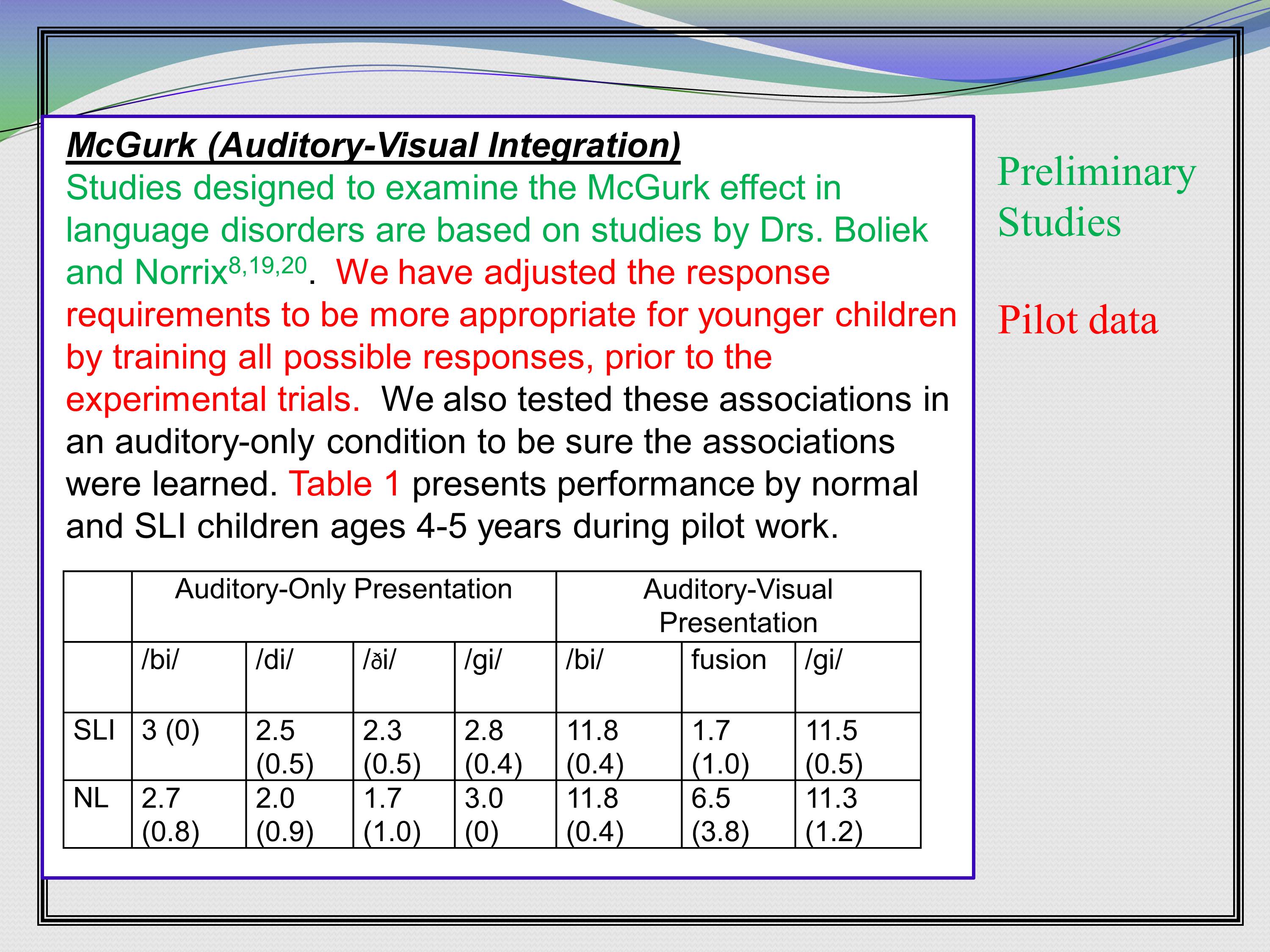

So here’s a nice lead in that actually distinguishes between preliminary studies and pilot data. This was in a grant that looks at the McGurk effect, if you’re familiar with that.

It says, “Studies designed to examine the McGurk effect in language disorders are based on studies by Drs. Boliek and Norrix.” who are both co-investigators on this grant, citation, citation, citation. So, if they’re published, they’re preliminary studies.

Then, here comes the pilot data. All these preliminary studies were in adults. So it establishes that the co-investigators have expertise in the McGurk effect. So, the pilot data is, “We have adjusted the response requirements to be more appropriate for younger children by training all possible responses, prior to the experimental trails. We also tested these associations in an auditory-only condition to be sure the associations were learned. Table 1 presents performance by normal and SLI children 4-5 years old during pilot work.” And there’s a table. With some data. That’s pilot data.

This is a technique I think is really nice. It’s a summary of the preliminary studies that identifies the problem that needs to be addressed going forward, and what’s needed to address that problem.

Recommendations are: Begin planning your preliminary studies way before your next grant. Because if you need to come up with some pilot data, you need some time to think about that. Again, this is why you want to be thinking about that next grant — whatever’s in the queue. My queue is still two grants away, but I already know what those grants are going to be, and the work to set those grants up is happening now.

Write your preliminary studies after you write the approach. Because that tells you what your preliminary studies should say. Initially, a lot of times as you’re writing the grant, it’s evolving with you. So, if you’ve already written the approach and gotten that all down, it’ll be clear what’s completely relevant and what’s a little tangential.

Provide examples that show technical expertise. Again you’re establishing that you can do the work.

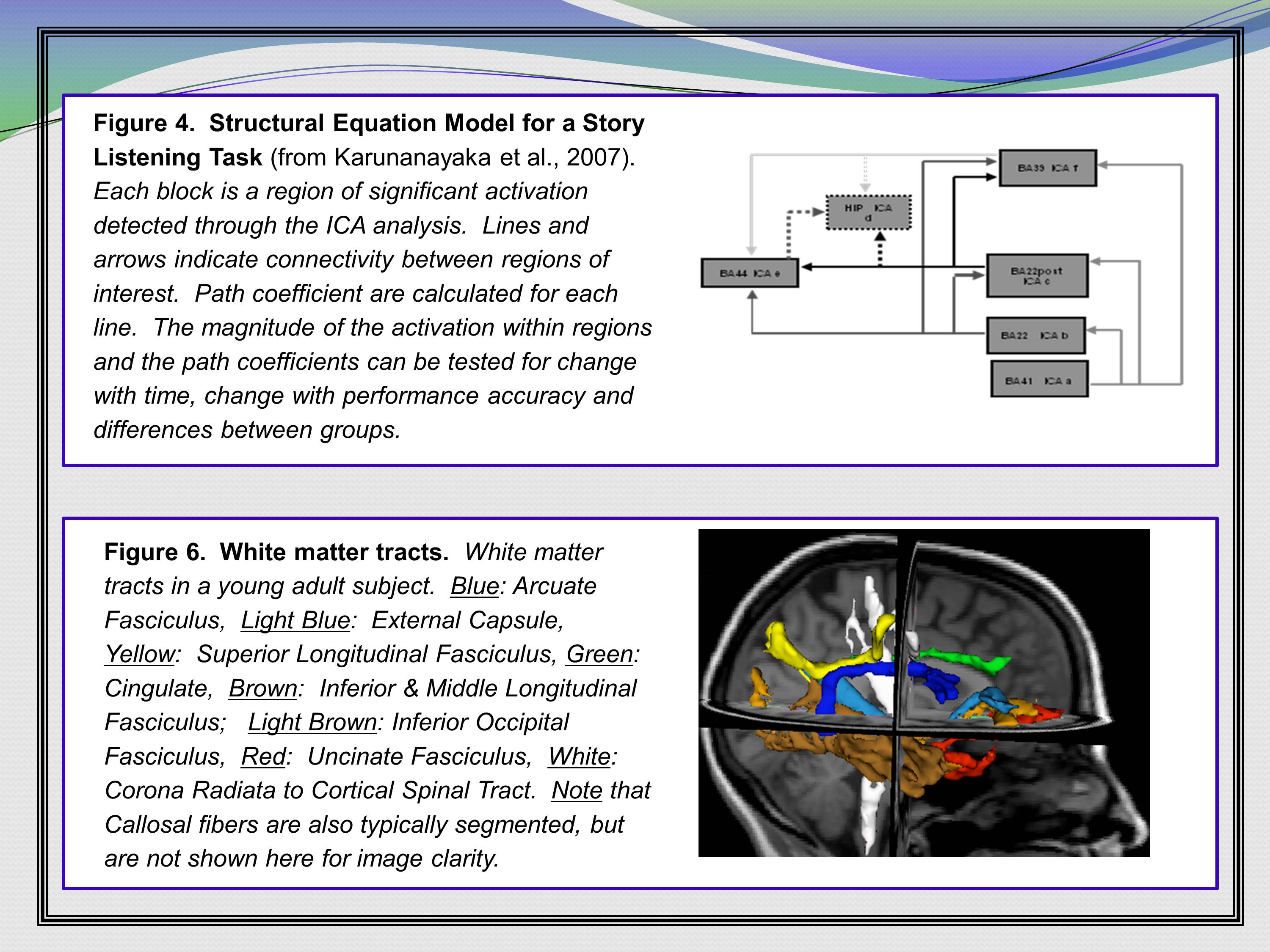

Here are a couple examples from one of my current grants that says, “Hey! We propose to do some structural equation modeling. Here’s a structural equation model that I’ve published. I obviously know how to do this. Because I’ve published it. I propose to do some tractography — here are some tracts, too.”

Recommendations: Make the point obvious with charts and graphs.

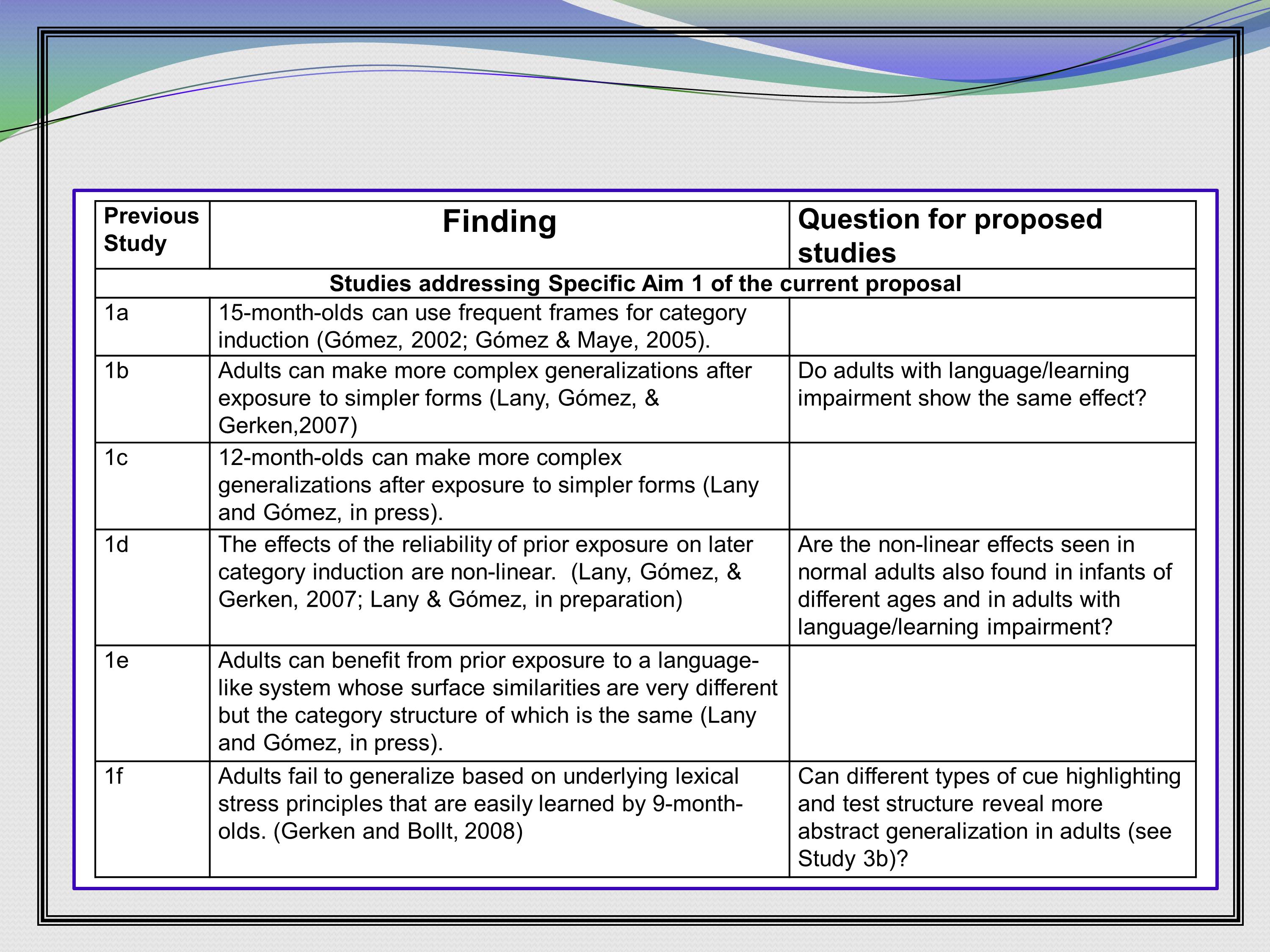

Here’s a really nice layout that I stole from — I think this is again LouAnn Gerken — where she lays out findings from her previous work (1a, b, c, d, e, f). And what questions they generated that the next grant is going to answer. This is a really nice way to lay out a lot of verbiage in a small amount of space.

I’ll tell you the reviews that came back said that the proposed studies were “well motivated,” and I think that table helped with that.

Another recommendation: Establish the history of prior collaboration for interdisciplinary efforts. So, certainly you should do it in your biosketch, but preliminary studies is another place to do it.

This grant proposal rests on the combined expertise of two investigators, each of whom have established records of research in their respective fields. Blah, blah, blah. However, we’ve never published before together. So, in order to establish a collaboration between the investigators, and to explore the feasibility of the proposed work — hint, hint, we’ve been working on this — we have collected pilot data. So, we’re basically saying, “We haven’t published together, but we’ve been working on this pilot data that we’re going to show you.”

Final Thoughts

Finally, we’ve given you so resources for additional sources to go to get some help.

The first resource is your program liaison.

There are some web links for NIH stuff. You’ll get a lot more of this from the NIH people. There’s a web link for the review process. The NIH page actually has a video clip of a review session. If you wanted to look at that you can pull that up.

Then a couple of books on grant writing. As I said, the Goldberg book is a little bit old now — there’s a couple of newer ones in here that are less extensive, but fine.

I really like this quote, which David Pisoni contributed.

“The only reason to write a grant is to get the money to do the research. Sending in less than your very best effort is a waste of your time and everyone else’s.”

I’ve said a couple of times that I write grants regularly. It’s not a special event. I’ve got a whole queue of them that are in various stages. But I never let a grant go out the door that’s not ready. Because it is a waste of everybody’s time.

Mario Svirsky:

Who knows Dave Pisoni personally around here? So, you’ll recognize it when I say, “Mario, Mario. It’s about getting the money.”

Audience Comment:

Going back to Elena’s very first point about cranky midnight reviews. My advice I always give is “Never, ever give a reviewer a reason to say no.” They want to say yes, but they know what the competition is like. And if all of a sudden something pops up and they can say no, that becomes very hard to ignore. So, everything you do, you should do according to format, make sure that it’s clear, it’s readable, it’s skimmable. Don’t have them say no.

Further Reading: Online Resources of Interest

Foundation Center. (2014). Proposal Writing Short Course. Online Training Courses: Quick Tutorials (Available from the Foundation Center Website at foundationcenter.org).

National Institutes of Health. (2012). Grant Writing Tips Sheets. Grants & Funding: Grants Process Overview (Available from the NIH Website at http://grants.nih.gov).

National Institutes of Health. (2014). New and Early Stage Investigator Policies. Grants & Funding: NIH-Wide Initiatives: New Investigators (Available from the NIH Website at http://grants.nih.gov).

National Institutes of Health. (2015). Peer Review Policies & Practices. Grants & Funding: Grants Policy (Available from the NIH Website at http://grants.nih.gov).

Further Reading: Books on Grantwriting

Gerin, G., Kinkade, C.H., Itinger, J., & Spruill, T. (2011). Writing the NIH Grant Proposal: A Step-by-Step Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Goldberg, I. A. & Ogden, T. E. (2002). Research Proposals: A Guide to Success. 3rd Edition. San Diego: Academic Press.

Yang, O. (2012). Guide to Effective Grant Writing: How to Write a Successful NIH Grant Application 2nd Edition. NY: Springer.