The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

We’re going to focus on Abstract and Specific Aims. The reason why we really focus on these, beyond the fact that this is the most widely read section of your grant, is that getting your Abstract and Specific Aims on paper is the appropriate starting point for a grant.

Megan gave us a really nice example of why that’s important. She was able to share those sections with a colleague, and through a discussion with the colleague, she realized she had the Abstract and Specific Aims for grant two, and she needed to do something else for grant one. So it was good that she found that out after only writing a page and a half, rather than after writing a six-page application and being on the verge of submitting it and realizing, “Oh, it’s the wrong grant.”

That’s why you really want to start early on these sections, send them around, and have other people give you feedback. So you know you’re on the right track with your ideas and the way that you’re pitching those ideas to your audience.

Fast Facts

To go to the slides, the Abstract and Specific Aims create a first impression of your grant. They are widely read sections. They are the only two sections that are distributed to potential reviewers, if SROs do get their reviewers in that way. Some SROs just assign reviewers without input from the reviewers. But others will send around portions of the grant, usually the Abstract and Specific Aims, to have the potential reviewers look at it and give feedback about whether or not they’d be able to review that grant and to what level they would be a match for that grant. Others have already noted that others on the panel are going to read those sections just to get a sense of what your grant is about. So it’s important that these be strong.

One other group that’s not listed on the slide, but we’ll be talking about on the last day, is Council, which is the group that actually makes the funding decisions. All they see of your grant is the Abstract. Just remember that. The person who’s going to decide if you’re getting funded or not only sees the Abstract. This is really important that that be strong.

Form Requirements/Instructions

In terms of the requirements, you see they are pretty straight forward. The Abstract is essentially going to be a paragraph. Your Specific Aims are going to be one page.

Specific Aims: The Basics

Instructions

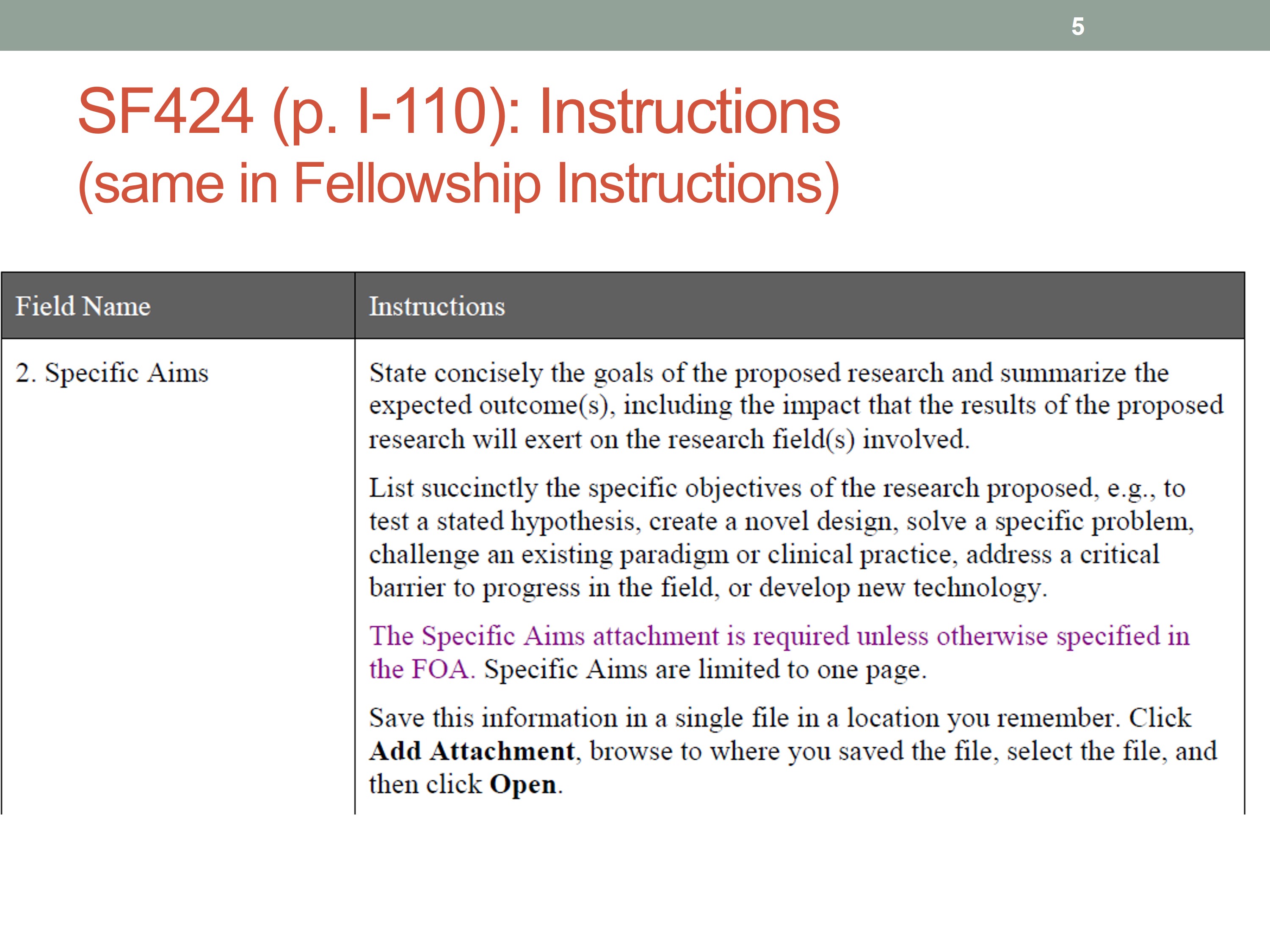

We’re going to start with the Specific Aims. This is the section of the instructions that talks about the Specific Aims.

Goals

What’s the goal for these Specific Aims? You want them to excite the reviewer. Again, this is the first thing that they read. You want them to think, “Oh, I want to read the rest of this, this looks really good.” Rather than, “Oh my God, how am I going to get through the next six pages?” Remember the reviewer starts out being your friend and wants to support you, but that support only goes so far. You have to earn it the rest of the way, to the end of the application. Be sure that you earn it on those first couple pages.

You also want to inspire confidence in you. It creates a first impression of you.

The other thing it does is it sets the framework for the rest of the application. So from reading the Specific Aims, they should really have an idea of the themes or questions that are going to guide this particular project. It really sets the overarching themes and goals that you’re going to carry through for the rest of the application. As they move through the application, there shouldn’t be any big surprises — the rest of it should be fleshing out what they read in the Specific Aims.

Essential Elements

Here are the essential elements. In general you are going to want to provide an overarching goal. What are the problems or issues that are studied in this application? And most importantly, why are they important? The theory, rationale, or the motivation — the why of the application. Why are we looking at this?

The approach. You might not be going into the approach in a lot of detail at this point. But it is a good idea to give some kind of orientation to what the approach is. Is it behavioral? Is it neuroscience? Is it genetic? What am I going to get myself into here?

Specific questions and hypotheses. We want to see specific goals that are going to be addressed by the particular studies. This is where we’re getting into a little more detailed view of what the application is about.

We also want to know something about the significance and the innovation of the work.

Analysis Checklist

Here is a little checklist that basically gets at those points, but in a question format.

Example

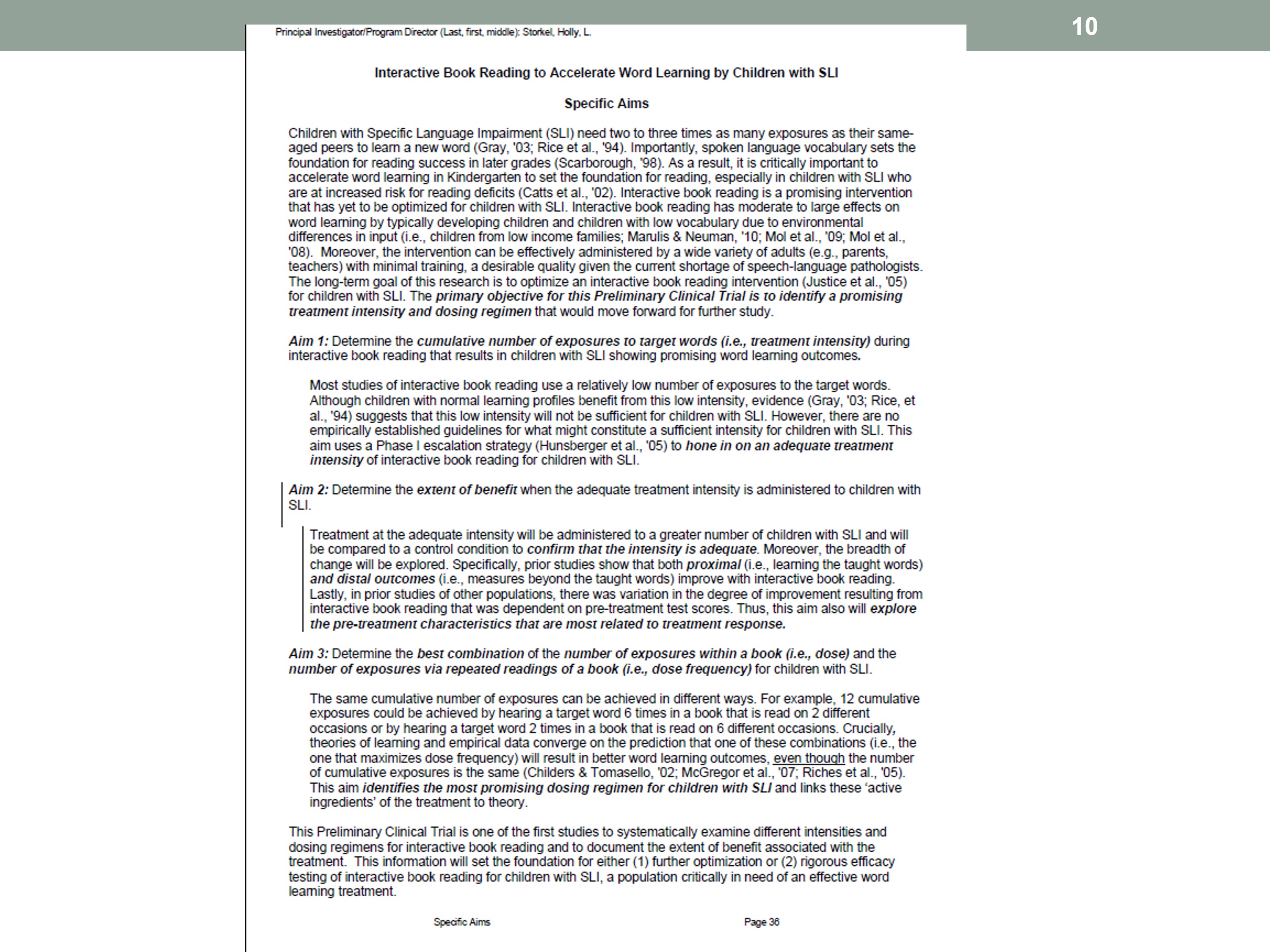

Now we’re going to look at an example. I’m using an example from one of my grants. Here’s what the aims look like. It’s one page, and you can see there are some formatting and some indents and some white space to make it a little more pleasing to the eye.

Beginning

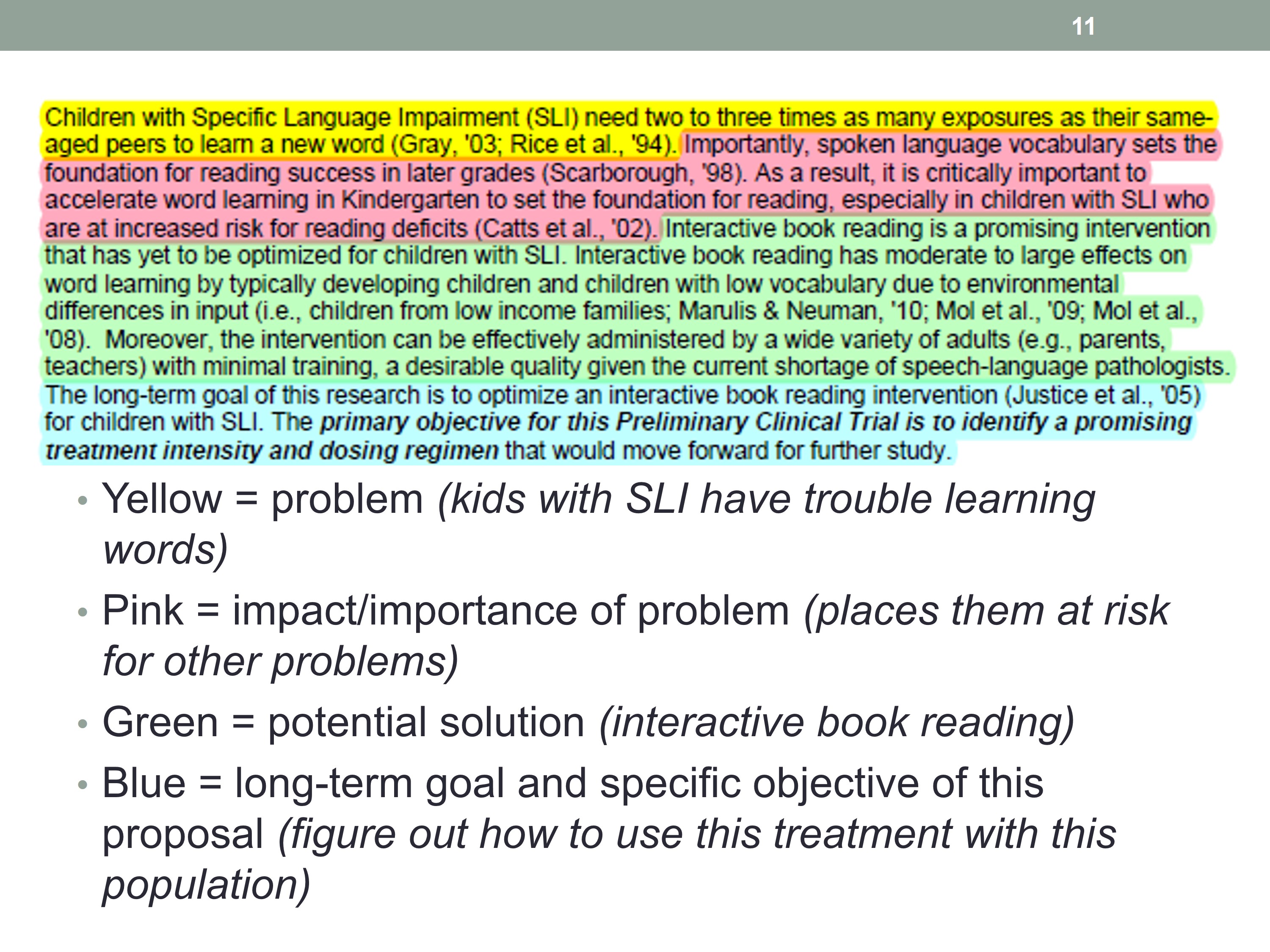

Now we’ll look in sections. I’m not going to read this to you, but what you should notice is that every sentence — or maybe every couple pairs of sentences — has a purpose. When you look at your own aims, realize that these are very short sections. You don’t have a lot of time to build up to a point. You need to make a point and move on.

When you’re looking at your aims, you want to be thinking about, “What is this sentence doing for me? How does this further my goal of being funded? What is this communicating to the reviewer?”

If we look at this example, the sentence highlighted in yellow is basically a statement of the problem: Kids with specific language impairment have trouble learning words.

The next section, the pink, talks about the impact or the importance of this problem: That places them at risk for other kinds of problems like academic failure.

Green is then the potential solution. This is a little bit longer section, it talks about interactive book reading and what that exactly is, so that someone is a little bit oriented to that.

The blue section goes into the long-term goal and the specific objectives of this proposal, which is basically to figure out how to use this treatment with this population.

Every sentence there has some sort of purpose. There is nothing that is just hanging out there.

Aim 1

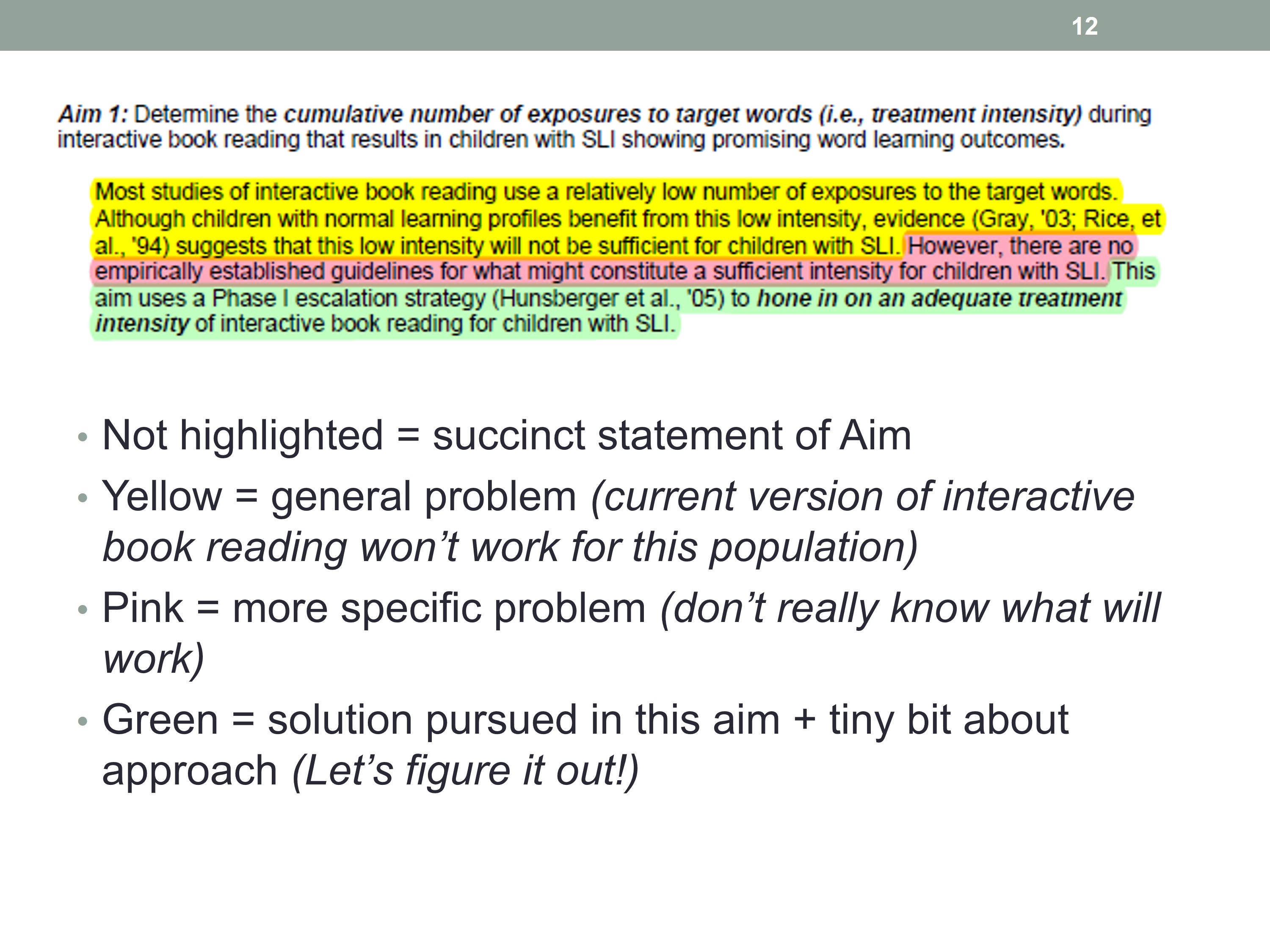

Then we go into the aim itself. The unhighlighted part, the white part, is just a succinct statement of the aim.

You might not be able to tell, but there are a couple of words here that are bolded. It is important to start building in the reviewer’s mind, what this aim is about. They need some language to be able to link to that aim. What is Aim 1 about? In this case the aim is about “exposures to the target words (i.e., treatment intensity)” that is needed for this treatment. You want people to start thinking, “Okay, Aim 1 is treatment intensity.” And they’re going to then be able to follow that through for the rest of the application.

The yellow is the general problem: The current version of book reading won’t work for this population. The pink is the more specific problem: We don’t really know what will work. Then the green is the solution that’s going to be pursued in this aim and just a tiny bit about the approach: Let’s figure it out, and we’re going to use a particular clinical trial strategy to do that.

Aim 2

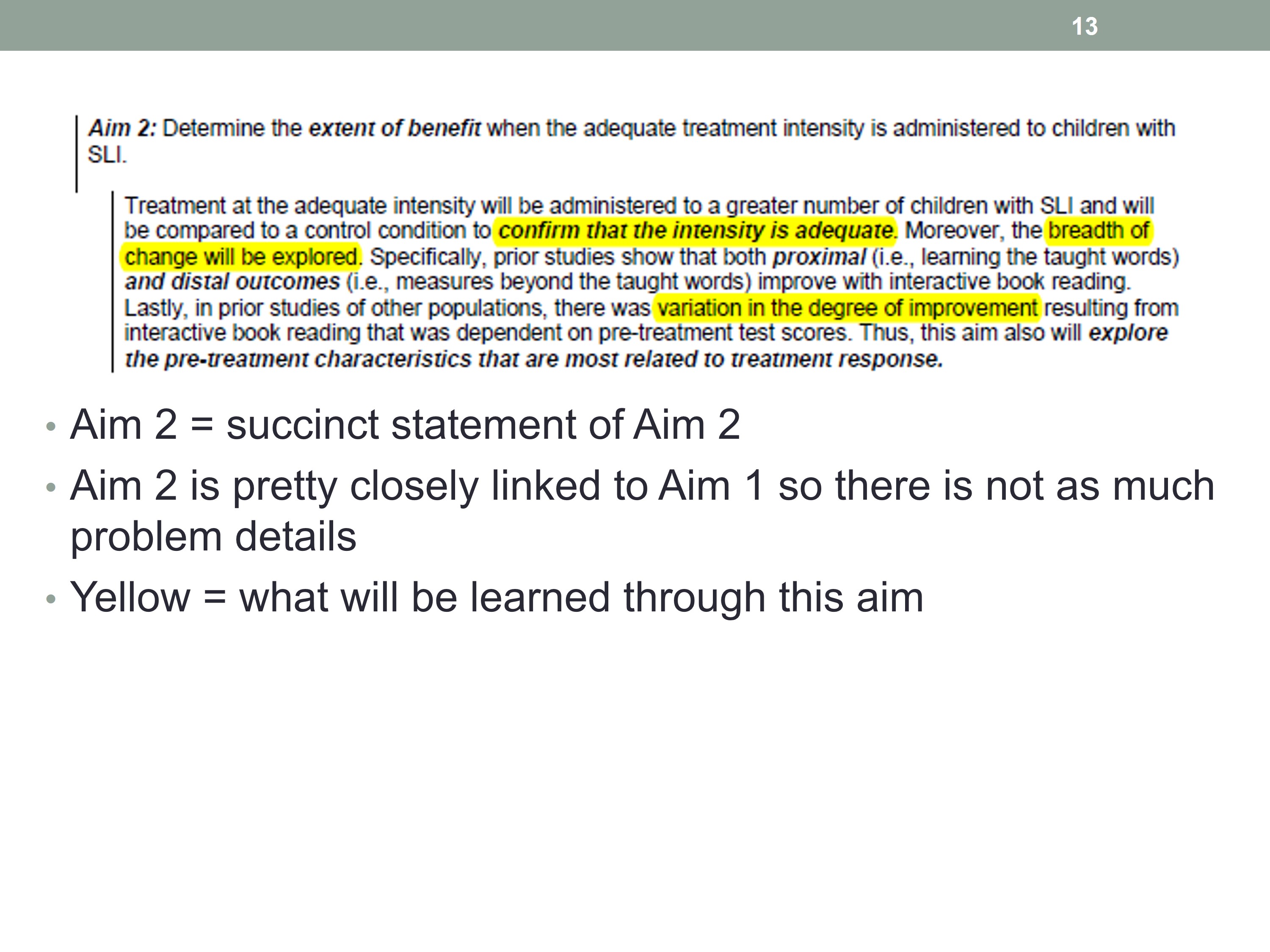

The other aims are set up in a similar way. Aim 2 is pretty similar to Aim 1, so there’s not as much detail there. It is mostly just setting out how it’s different, and what’s going to be learned through this particular aim.

Aim 3

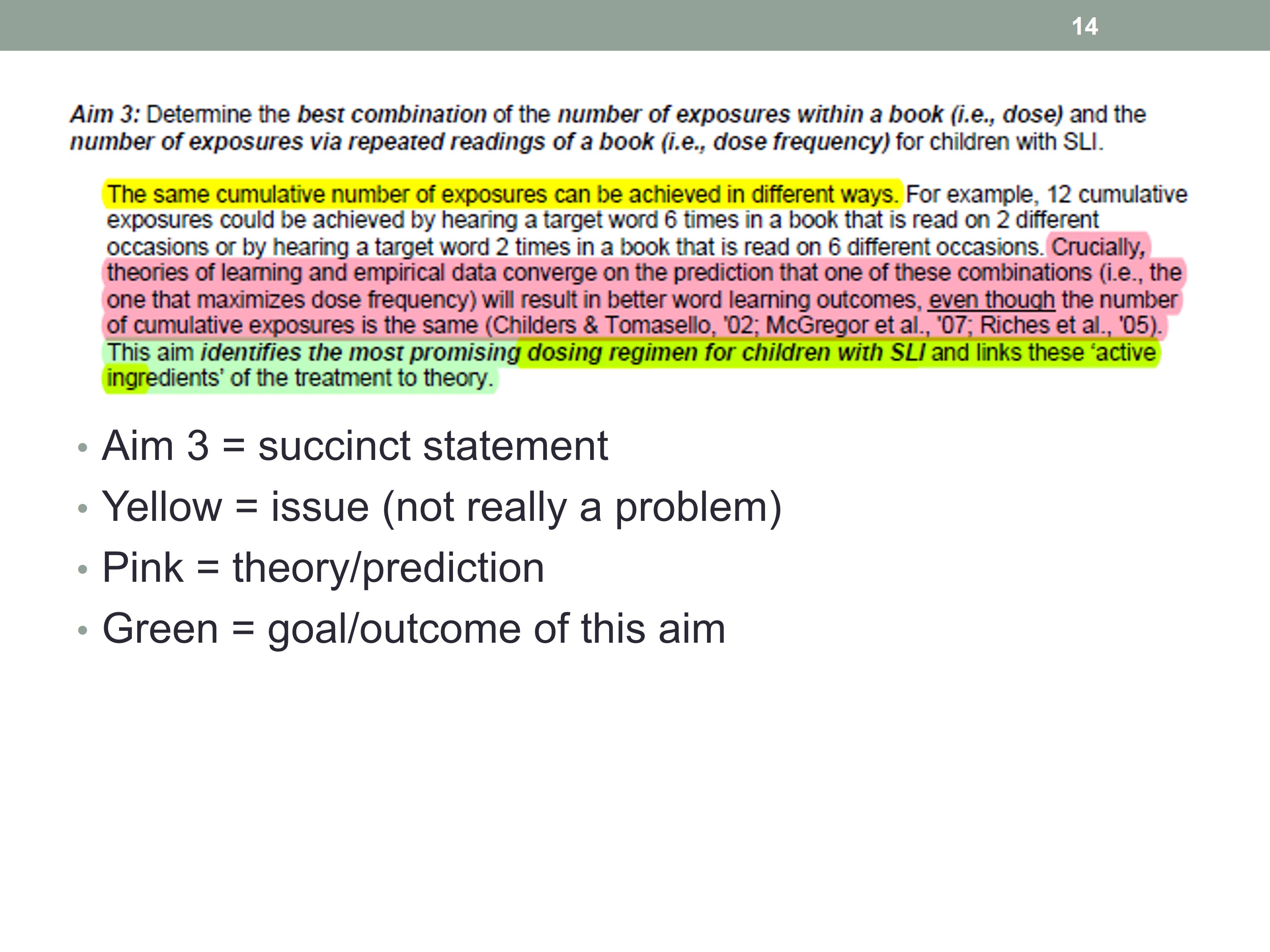

Aim 3, again we start with the succinct statement of the problem. Here, the yellow part. It’s not really a problem, it’s more of an issue — that we can achieve the same number of exposures in different kinds of ways. That’s not necessarily a problem, but it’s the issue that’s going to be addressed. The pink is some theory and prediction about what way is going to be best. And then the goal or the outcome of this aim is shown in green: At the conclusion of this, we’ll know the best way to do this.

Conclusion

Finally in the Specific Aims there is this kind of concluding section which is a summary of the aims. The yellow is the summary of the outcomes or the predicted accomplishments. Then the pink is the next step further.

I have a note here that that was a little bit boring. It sort of trailed off here. Probably I needed to reduce some things in the other portions of the aims and pump this up a little bit, and incorporate a little bit more detail here about the impact or significance or the work to close off in a stronger way.

You want to go through your Specific Aims statement, and deconstruct it this way. See what every sentence is doing for you, and how it accomplishes what’s on the checklist in setting up the important points.

Abstract: The Basics

Instructions

Now, as we look at the Abstract, here are the instructions.

Goals

The goals of the Abstract are pretty similar to the Specific Aims. You want to invite and encourage the reviewer to read the grant. You want to excite the reviewer about the research and inspire confidence in the PI. You are going to notice a good bit of overlap between your Aims and Abstract, and that’s okay. You want people to be building up this idea of what the grant is about.

Essential Elements

The essential elements: You’ll need an overarching goal. You want to say a little something about the approach, just to orient people to where you’re going, and also to make sure you get people with appropriate expertise as reviewers. And you want to be highlighting the significance and the innovation.

Analysis Checklist

Here’s another checklist.

Example

Here’s an example from the same grant. It’s about half a page. Since it’s half a page, you don’t have any room to put in more spacing or creative things.

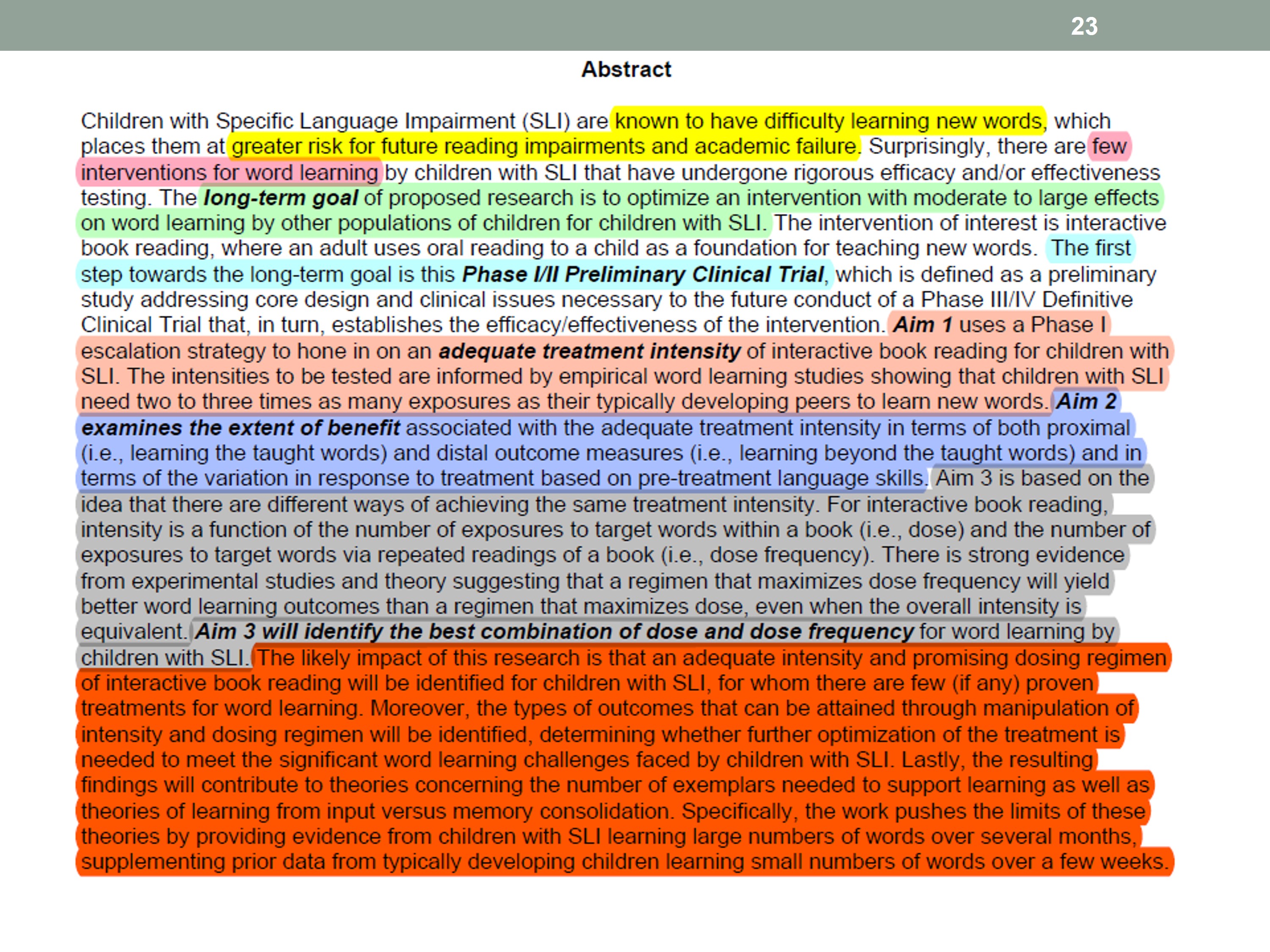

Example Deconstructed

Once again we can deconstruct it. Again, I won’t read it to you, but it’s color coded according to what the main points are. You’ll see a lot of similarity with the Specific Aims I just showed you.

Deconstruction Key

The yellow part, which is at the very beginning is the general problem: Kids with SLI have trouble learning new words. You might remember that from the

Specific Aims.

The pink is the more specific problem that will be addressed: There’s few effective treatments or proven treatments.

The green is the long-term goal: To adapt a known treatment for use with this population.

The blue is the current step towards the long-term goal: A preliminary clinical trial. And part of that gets into the methodology, to get the right reviewers who are familiar with clinical research and the methodology involved in that.

The aims then are given in brief. You’ll see each aim is shown in this abstract. Where Aim 1 is peach, the next color bluish/purplish is Aim 2, then the gray moves into Aim 3. All of the aims are included in the Abstract, at least to some degree. And once again, you’re trying to establish some basic terminology that people can link to your aims. The peach aim is about adequate intensity, the blue/purple is about the extent of benefit, and the gray is about the best combination.

Finally, the orange section comes around to the outcomes and impact. I thought this was better than what I had in my Specific Aims. It’s a bigger section here, so I spent more time developing that. That would have been good to incorporate into my Specific Aims — that level of detail and those particular points.

General Tips

Many people write these sections as an afterthought. As we’ve talked about, that’s terrible. This is where you want to start because it sets the whole framing for your grant. If it’s going in a bad direction, you need to know now.

Start here and share these with mentors immediately. Get some feedback. Talk through why you’re putting things the way you’re putting it, what the major significance and impact is. Make sure you’ve got a good message at this point, before you move forward writing the entire grant.

Both sections should be concise. As you saw, one half to one page, depending on which one we’re looking at. That means that you really need to get out anything that’s unnecessary. Make sure you are trying to use straightforward terminology so you don’t have to define terms in your Abstract and Specific Aims, or that you can put some very concise reference points for those terms. You don’t have time to build up information. You need to just state the facts and get the major points out there.

Make sure you have new information in each statement. You also don’t have room to be repetitive here or reiterate. They are short sections. People should be able to follow along with what you’re saying and not need a lot of repetition in these sections.

Finally, both sections need to use powerful and compelling language. Just saying that there will be clinical implications for the work — that’s not powerful. That’s very vague. That’s not compelling at all. Really think about how you’re saying the impact that’s there. Try to put it in words that are going to be very compelling to others and very exciting to others.

This is really your first sales pitch. If you get this sales pitch right, at this early section before you write the rest of the grant, you’ll know the kinds of pieces that you really want to play up in the other sections of the grant.

You need to write for a “semi-naive” audience. You want to avoid jargon, or provide short and clear definitions of crucial terms. If you do need to use technical terms, pick a single term and stick with it. Remember that not everyone who reviews your grant is going to be an expert in your area. Particularly when Council is looking at these. Council is a broad group of people, including folks from the community as well as scientists, so you really don’t want to be miring them in jargon when they are going to try and decide whether to fund your research or not. You want to make it compelling to a regular person who isn’t immersed in your area of acronyms.

Ask others to review these two sections extracted from your grant. This will give you a sense of how reviewers might react to it. If your internal reviewers are not excited about these sections, you need to keep working. Maybe you don’t need to revise the grant totally, but maybe you need to revise your sales pitch for the grant, or the way you’re explaining the impact that you’re trying to sell to get the right message that people are going to find compelling.